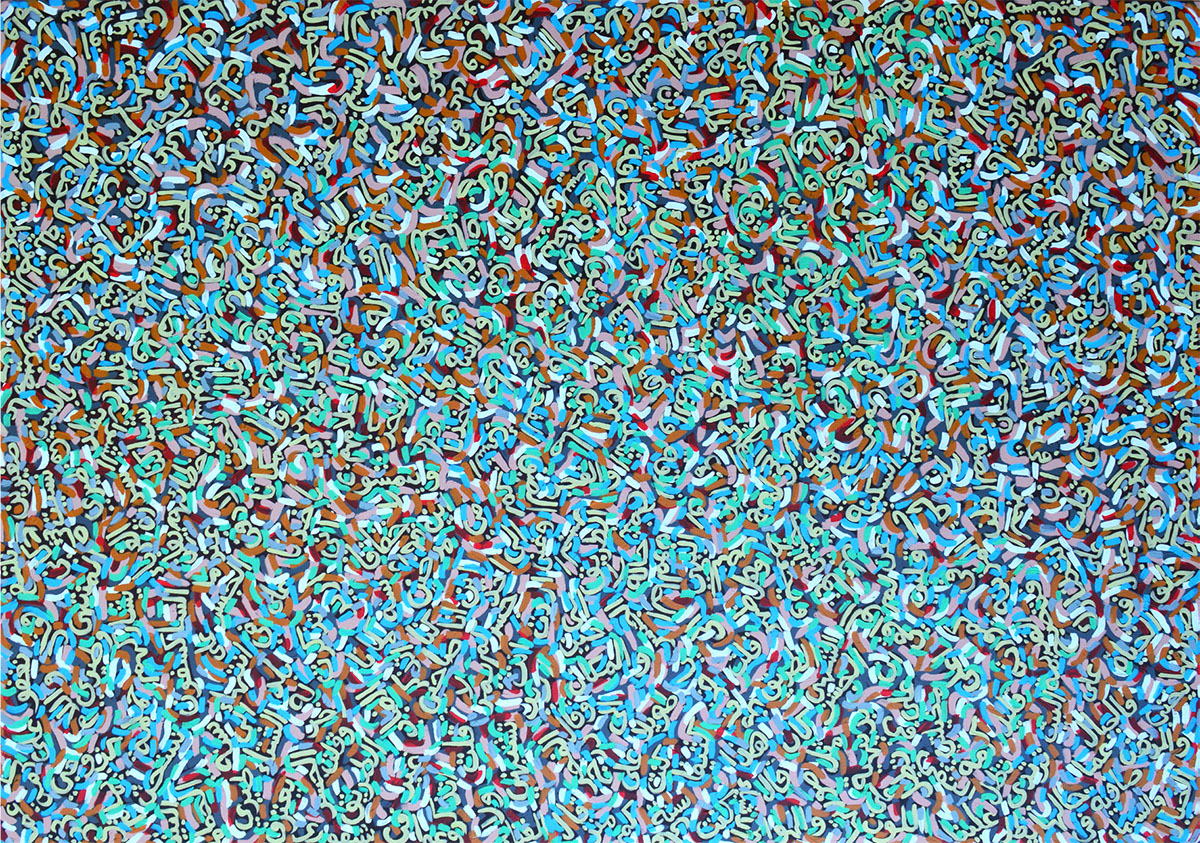

Fouad Agbaria’s body of work is a fragmented and divided project, ranging from Impressionist nature to Abstract and thence to calligraphy, all predicated on the artist’s license to distribute, disrupt, construct, and deconstruct. Agbaria is an Abstract artist in the full sense of the word, one who migrates among styles. His artistic project amalgamates diverse elements, some constant and others variable. He expresses rhythm in his works by relying on and anticipating repetition that he realizes by means of continuity, order, disorder, harmony, and disharmony…It is evident, too, that Agbaria is strongly influenced by Sufism, as manifested in circular movement, letters in motion, and mixing and matching of light and darkness. —Aida Nasrallah

Fouad Agbaria (فؤاد إغبارية)

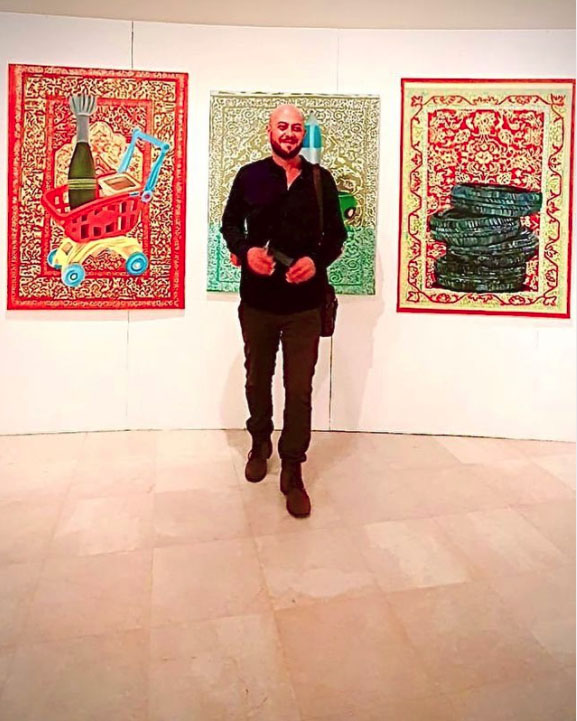

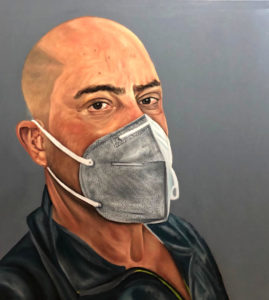

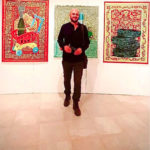

Born in the village of Musmus near Umm El Fahm in 1981, Fouad Agbaria earned his BA from Bezalel Academy, Jerusalem in 2004 and an MA from Haifa University in 2014. He is one of the busiest artists of his generation, among those who are continually redefining what it means to be Palestinian west of the old Green Line.

As his Ramallah gallery, Zawyeh Gallery, notes, Agbaria has painted prolifically, often experimenting with different styles, techniques and media including charcoal, oil, acrylic and lithography. His catalog of work to date has dealt with themes associated with the Palestinian narrative, identity and memory. He has participated in over 20 group exhibitions and has held several solo shows, including “Maps of Memory” (2018) and “Nostalgia to the Light” (2015). He participated in the group exhibition, Art on 56th, in Beirut in 2016 and several other group shows in Nazareth, Jaffa and Tel Aviv.

Fouad explains to TMR, “I am happily married to a wonderful woman named Manar, a social worker for the local council. She has been very supportive and always encourages me to follow my dreams. I’ve been blessed with three beautiful children, Selen, Mohamad and Adam. Although my passion is art, my day job is a driving instructor, and I also teach art at colleges, in particular drawing, painting and sculpting.

“My father was a Hebrew language teacher and my mother a modest housewife. From a young age I was raised by an iron fist and a tender heart.”I was lucky enough to be born in an area which was surrounded by breathtaking scenery and perfect landscapes, and although sadly there were many army training bases, I was still able to find calm and beautifully untouched stretches of land, which were a major inspiration for me in my map of memories.

“My grandfather was a traditional Palestinan farmer and from a young age I spent most of my spare time helping him with all his daily chores, including ploughing the land, tending livestock and harvesting the crops. He was a lovely man and I enjoyed every precious moment with him even though he was very strict.”

Fouad adds: “A few other important memories that gave me inspiration were the vast amounts of prickly pear cacti (sabra) that were common in our area. They were used to protect personal space as a natural wall, and also produced beautiful colored edible fruit. What is special about the cactus plant to me is first of all its ability to survive and grow in tough environmental conditions; I also found it amazing that a plant to the naked eye looked dead had the ability to create life from within itself. In an artistic sense, the cactus stem — be it full of razor sharp thorns — was extremely soft and smooth. To my young eyes this was visually very moving.”

The landscapes around Agbaria’s home village of Musmus, not far near Umm al-Fahm (in the Galilee) are clearly the inspiration for his many landscape paintings, often featuring the wheat harvest or the sabra (prickly pear cacti) — a symbol he recuperates from the Israelis who adopted it as their symbol for native toughness.

In a recent catalogue, the artist commented: “In this day and age, time rushes by and events travel in a flash of light, leaving us at a loss. With the recall of childhood memories and recollections that refuse to budge and wither, such as letters and words that make up the story of a nation. Words sway between good and evil, love and hatred, and devastation and hope in their journey in search of light. Within cactus fences lies a fable that tells the story of a struggle between right and wrong, containment and safety, and a memory shedding light on an abandoned home and an assaulted land, refusing to be defeated, with all its sweetness and thorns/bitterness.”

An excerpt from Foud Agbaria’s statement: “My World of Painting: an Emotional and Cognitive Refuge”

During my academic studies at Bezalel, my works concerned themselves with tearing down and rebuilding, making a mess and cleaning it up, just as in my childhood I dismantled my toys only to put them back together again. I wanted to wipe off the soot from the ugly surface and expose, in a dialectic act, the unbridgeable opposites of ugliness and beauty, of black and pure white.

I also made attempts to revive decorative-mold art in practice works using charcoal, graffiti, and lithographic printing. I tried to position symbols of the culture that I had inherited within the jumble of schools and styles that had little to do with me, to describe the dualism of innocent beauty, and to propose ways of resolving their contradictions.

When I finished my studies, I chose to return to the area of my birth—to Umm el-Fahem—and make a living there as a driving teacher. Thus my life proceeded in two parallel systems: “real” life and artist-life. Indeed, I engaged at this time with the gulf that separated my dour quotidian routine from my life as an artist. I tried to point viewers in the direction of the scenery of my childhood in Musmus as I reexamined the boundaries of the location as a sober and socially and politically aware adult.

I see the prickly pear as a symbol of survival. Even in abandoned places and destroyed villages, it remains in the landscape like a signpost, affirming its existence and standing over the village like a sentry.

The prickly pear appears in large works that are typified by optimistic bold multicolor embroidery and finds expression in various ways that extol its cyclical and indomitable nature. It is painted in the form of a wall or a rampart, bristling but also yielding rich nutritious fruit in which sweet memory is imbued. Sometimes it represents a perfect world; here the cactus is complete, leaves and fruit included; at other times it is a graying, crumbling bush, symbolizing destruction. This destruction, however, is temporary; from its decrepitude the prickly pear will regenerate itself, turn green, and again give forth its sweet, nutritious fruit.

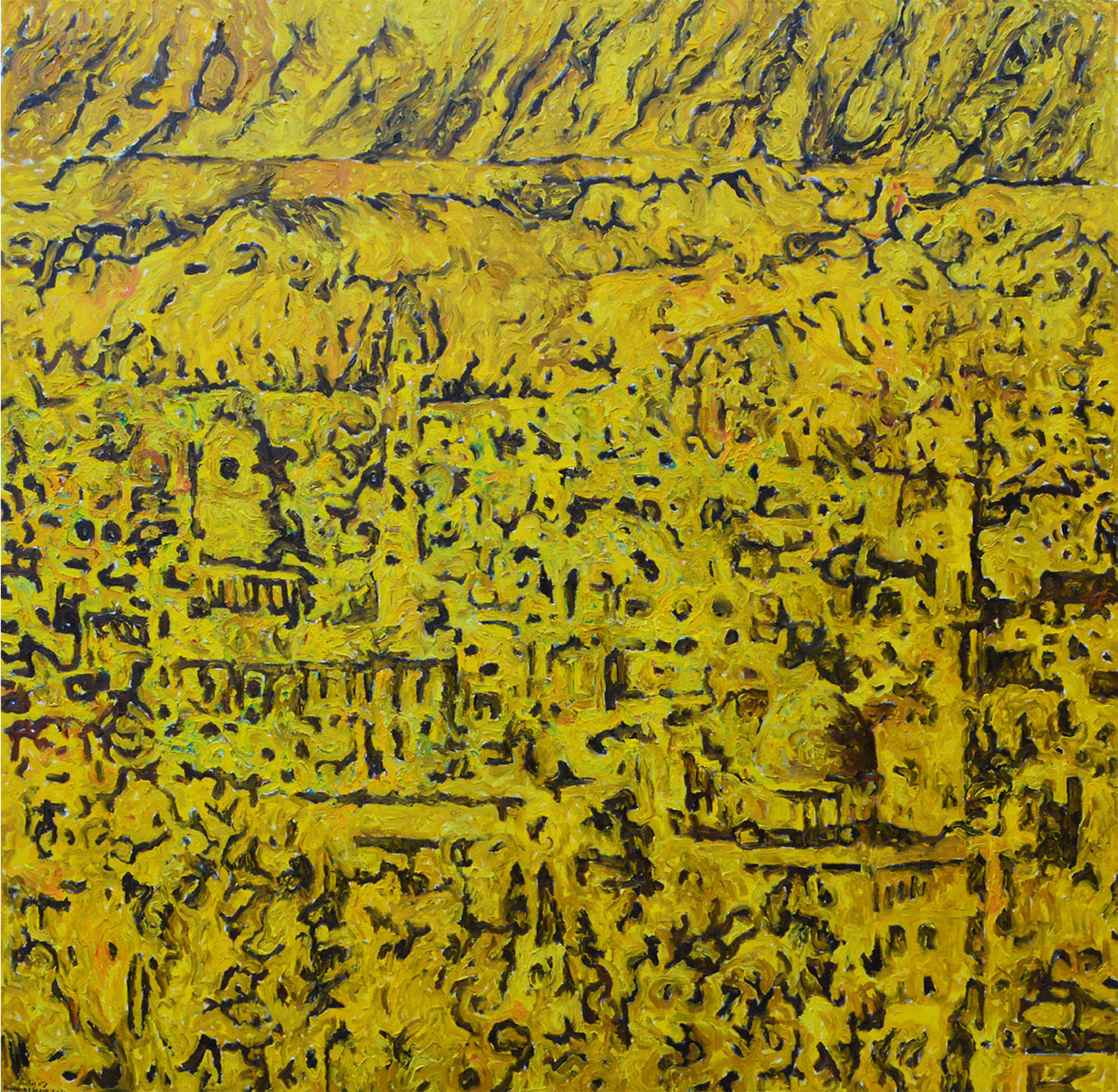

In more advanced stages of my work, I lead the prickly pear to a place of deconstruction—a symbol of the disintegration of Arab society. I fill the canvas with a model of prickly-pear leaves dipped into a platter of yellow and brown contour lines. Here one finds nothing complete that can be grasped. In other works, the same childhood landscape is treated to decorative graphic flattening as an expression of pain and sorrow for the location, which has been defaced and trampled by an angel of destruction represented by bulldozers. The flattening of the scene expresses a criticism of the State of Israel, which does not allow life and building in this childhood landscape, thus rendering it useless.

Later works express a profound frustration that traces its origins to the problem of my status and identity in Israel. The critical contemplation neutralizes the remaining colors, which contract into a platter that accommodates only shades of yellow and brown. The images to which I relate are greatly simplified. In “Checkpoint,” I describe a soldier aiming his rifle at an Arab and ordering him to undress. The painting attests to a personal experience that I had while attending Bezalel and living near Jerusalem, having to cross checkpoints each and every day.

In recent years, my work has been expressing my search for the transition from techniques to development of ideas. I move between technical and cognitive worlds, returning and seeking expression within and through colors. The works are typified by free brushstrokes and knife etchings of gridlike lines of width and height. Layers of gray and black add motion to the painting, allowing the yellow to rise and overshadow the other hues without destroying their harmony. By etching into the paint, I lend the flat painting a measure of power and acute expressiveness. One who views it from up close may think that I used a needle and thread to produce the effect because the etched lines create the impression of cloth texture. This engraving technique evokes a childhood memory in me: a man who used a needle and thread to produce straw brooms. As a boy, I waited eagerly for the “straw-broom maker” to visit our village, as he did at grain harvest time. Passionately I looked forward to the moment when I would sit at his side and watch him create those brooms with his nimble flying fingers.

The singularity of any artistic act is inseparable from the shaping of heritage. Heritage is fundamentally a living force and, as such, it changes radically. A sculpture or a monument of Venus may appear in forms other than its Greek one, the one that made it respectable and valuable, differing from the gaze of the mediaeval nuns who considered it as vile, as an idol. Both specimens, however, vie for absolute hegemony. Here lies the unique characteristic of transposing an action from one historical era to another, each specimen copying over a heritage and a culture of the time.

Etching in paint is a dualistic act in that it both reveals and conceals a surface. In my recent works, I express the aspects of the suffering that I experience, including collective and self-critical aspects in order to create a tight bond between my artistic endeavors and the society within which I live, with its abundance of problems.