Jenine Abboushi

Gaza and Rafah are part of Palestine, historic to present-day. We did not need the May 2021 uprising that started in Sheikh Jarrah and spread over all of historic Palestine as proof of this, even if this unity galvanizes us. Our lives, families, friendships, memories, and longings are ever intimately connected. With each new Israeli war, wall, imprisonment, and theft, our experiences of forced separation draw us closer together. Particularly in the case of Gaza and Rafah, a vast Israeli-controlled prison, and in the case of Jerusalem — confiscated by Israel outright and against international law in 1980, reinforced with ongoing appropriation, neighborhood by neighborhood, house by house — the Israelis and international media have taken to labeling Palestinian land, towns, and society in amputated pieces. This way, there can be little or no mention of Palestine, the Palestinians, or their historic and contemporary struggle for freedom. Gaza, “Gazans,” and “Jerusalemites” (a special identification for residents as opposed to citizens), as referents, are deployed to sever Gaza and Jerusalem from all of Palestine, land and people. And so international communities can limit themselves to concern about Gaza on humanitarian terms (as the poorest place on earth), seemingly unrelated to Palestinian rights and struggle for justice.

The black and white Gaza photos from 1962-63 that adorn this essay tell a small story of cruelty of human and historic magnitude. In the early 1940s, Umaima Alami Muhtadi’s father purchased in Gaza a 100-dunum bayyara, an orange orchard. From their homes in El-Bireh and Ramallah, her family and children went there on weekends. Her mother and two brothers soon settled in Gaza, where her youngest brother Naim tended to the orange orchard, and her eldest brother Salah worked for Star, an orange-flavored soft-drink bottling company.

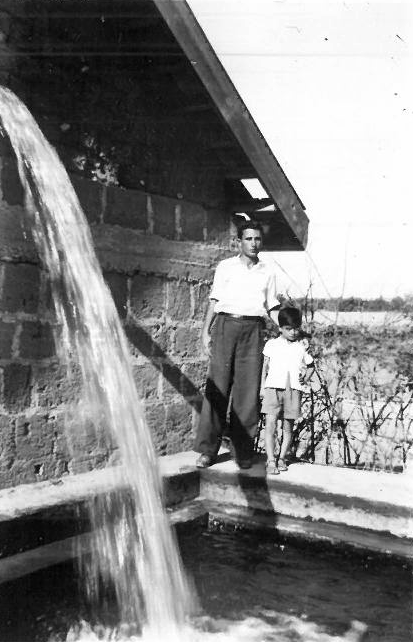

Umaima’s son Khaled, my high school classmate from the Friends Boys School in Ramallah, tells me about the well, 10 meters in width and over 50 meters deep, which was powered by an enormous diesel motor pump with big rubber belts that drew up water to fill the irrigation pool (shown in the photo of the cascade, with Umaima’s cousin Hisham standing next to her son Sameh). The pump made a loud, rhythmic, whistling noise like that of a train approaching from afar, so that indeed from afar farmers were reassured that the motor was turning well. The water, fresh and cold, was distributed into channels to flow to all the trees in the orchard. Khaled’s uncle Naim would push them into the pool to cool off on hot days.

[As hot as Gaza and with sunlight as dazzling was Jenin in the summertime, where I sometimes could persuade several of my female cousins to swim with me in the cool, deep irrigation pools, high above ground in my grandparent’s bayyara. Stripped down to our sun-blanched underpants and bras (mine slight and soft-cupped, and my cousins’ impressively armored), we felt hidden by the lush citrus leaves and potentially betrayed by our mirth and splashing. Some delicious afternoon swimming after cleaning my grandparents’ house mornings, followed by lunch and dishes, lounging on metal-framed beds within the cool stone walls and high ceilings until the magic hour of 4 pm. It was then when my grandmother, Taita Nazla felt assured that the snakes have taken cover and the sun has softened, so we could venture out.]

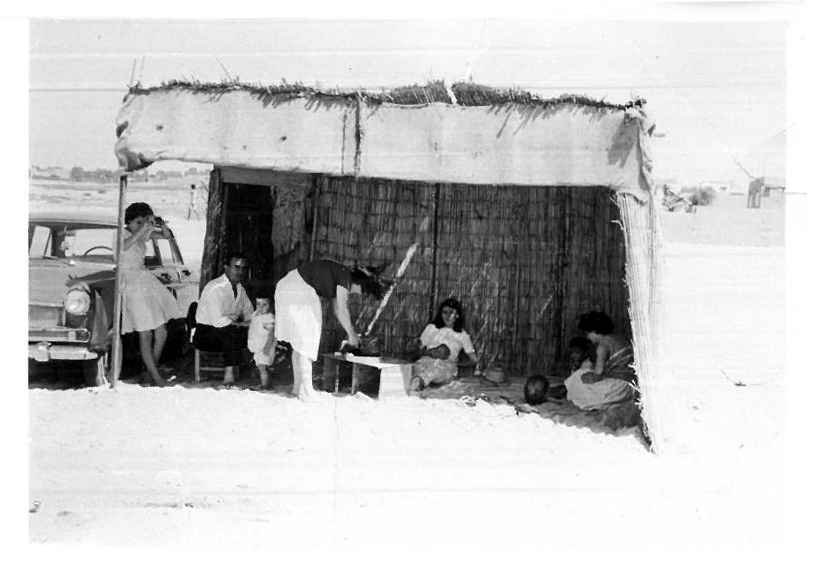

Soon enough, the Israeli occupation forbade the use of these pumps and canal systems and enforced the use of the drip irrigation system in Gaza and elsewhere in Palestine. More efficient no doubt were these ostensibly ecological restrictions, especially in saving water for the Israeli settlements’ agricultural projects and swimming pools, hidden yet surrounding the Alami family’s bayyara, sucking in over 10 times Palestinian water quotas per capita. During the First Intifada when settlers from Netzarim were reportedly attacked on the road to the bayyara, the Israelis chopped it down along with ten neighboring bayyaras. Netzarim was the settlement Khaled and his family used to pass at the end of their long days of work picking and sorting vegetables, heading to Gaza city, where the next morning they would unload the produce to be sold in the market. In late afternoons the family would go to the beach to relax under a rented palm-leaf 3areesheh that would afford them cover.

When the Israelis withdrew from and entirely closed off Gaza in 2005 — which they actually started incrementally with their separation wall in 1997, requiring special permits to enter Gaza — Umaima and her children were soon separated from her family entirely. Today the border is still sealed to nearly all but Israeli bombs. Over the years Umaima in vain solicited 12 Israeli officers to obtain a permit to cross the border and see her family, especially her brother Salah who had fallen sick. When he died in 2010, she had not seen him in ten years.

In Jenin the Israelis did not need to cut down the family bayyara because my uncle Hani did it himself, desperately lacking water to irrigate the citrus trees. We drove by years later with my then 5-year old daughter Shezza, perched and alert in the back seat of my uncle Walid’s rented car, and with our Hajjeh Radiyyeh sitting next to him in front, her crisp white cotton head-coverings ever gleaming in the sunlight. My Amu Walid pointed out where the family citrus orchard used to be. Prompted by mention of the bayyara, Shezza sat up straight and announced: “Quss ukht el-israeliyyeh! They drew up all the water from under the ground for their settlements and now we have no bayarra,” stunning us all by her curse, making the family laugh for days every time we pictured Hajjeh Radiyyeh receiving Shezza’s deposition.

For lack of water my Amu Hani even had to cut down the citrus trees in the garden of our grandparents’ home, including the grand bomaleh and sweet lemon trees. At first, he planted some impertinent rose bushes along the walkway leading to the house, perhaps to console himself and us all, but even they had to die. My Amu Hani himself died too young from a diabetes complication provoked by lack of simple medication and emergency medical care. He left this world in an ambulance on the way to Afula hospital just north of Jenin, blocked at the border, despite my Amu Walid (a doctor in Munich) and my father’s attempts to make contacts in Germany and the USA, respectively, to pressure the Israelis to let my uncle in. My Amu Hani, delirious in the ambulance, was missing his long-gone uncles. “Meskeen, poor Abu Bashar!” Hani was reported as saying, “he died when a bomb blew his penis off!” Amu Hani’s fever-humor resembled him and made us laugh and cry at once.

When my father Wasif arrived in Jenin in 1973 to introduce to his family my mother Leah and brother Mark Shareef and myself, we found a system of aqueducts throughout the town, with one passing through the muntaza (a café garden, common to most towns and villages) where my grandfather, family, and friends would sit with water pipes and play backgammon or swap jokes and stories. Jenin was lush, a garden, good to its name (jenin, junaina, janneh — to conjugate the town’s name leading to paradise, the root-word). Gone are the aqueducts, the overflow of flowering plants and verdure, too, even if Jenin is still a pretty northern town, surrounded by gentle hills and farmland. But today from afar it seems to me unforgivably less pretty since Cinema Jenin — where we grew up eating bizr, seeds, and watching kung fu and Hindi films — was cut down by Jenin developers, replaced by a shopping mall.

Porches and Courtyards

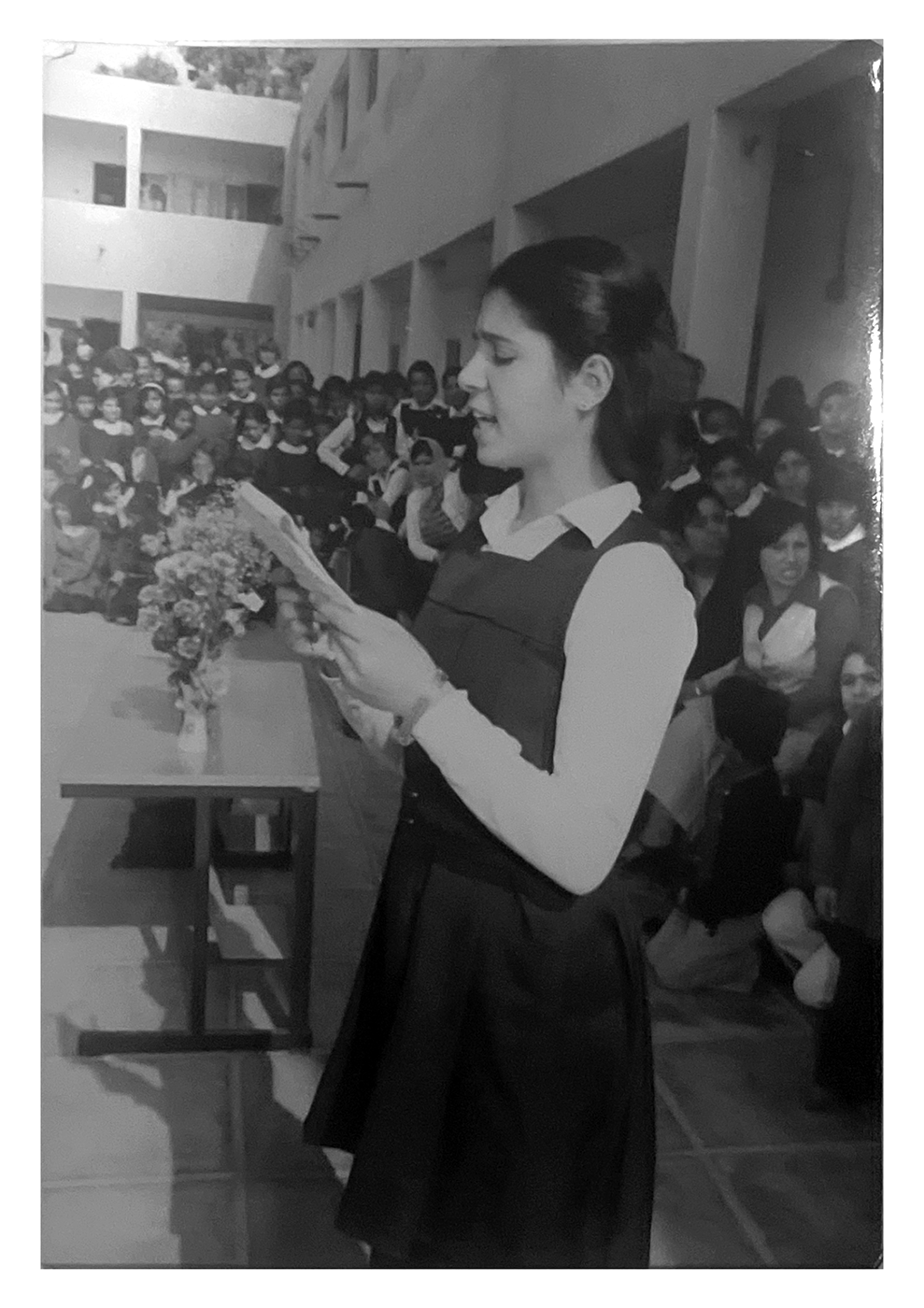

Birzeit University on the West Bank in the 1980s included many students from Gaza, and our friendships tied our worlds and families together until this day. My dear friend Laila Abu Ghali, an engineering student from Rafah, often came home with me in Ramallah for lunch or to hang out afternoons if we did not have class. She was gentle, a keen observer, and she used to say that if she could be what she wanted she would be a painter. She had long, soft black hair and dark brown skin, and channeled inventively her repressed longing. She loved to listen to radio programs, as I discovered when I visited her in Rafah and we sat directly on the cool tiles in the courtyard of her family’s modest home, and Laila showed me her small shortwave radio. She listened to the BBC and Egyptian programs. Her family is Bedouin, and Laila asked her brother, who traded in colorfully hand-embroidered black thoubs, to bring them out so we could admire their wild beauty.

We walked once in the late afternoon to the Rafah border that divided the town through the middle since 1982 when Israel returned the Sinai captured from Egypt in 1967. We watched people converse by hollering through the fences, barbed and electric wire, across the sand patrol road used by Israeli army jeeps, through the same barriers on the other side, to their family and friends they could see only in pieces, through layers of metal grids. Laila and I joined them in leaning against the fence, looking across in anguish and longing to the other side of the partition. Laila pointed out a woman down the barrier from us, telling me how Israeli soldiers a few weeks before shot dead her 12-year old daughter with cognitive disability on this very sand road, as she had somehow crossed over — no one knew how — and she was last seen by townspeople skipping along the sand patrol road, chattering and laughing freely as she did through the streets of Rafah every day. Laila said she was probably on her way to her aunt’s house to see her cousins as she used to daily before Rafah was split in two. The child’s mother had 11 children, she explained further, and yet was understandably inconsolable, weeping and mourning ceaselessly for her little girl.

I did not see Laila again after our graduation in 1986, even when I returned to visit Palestine because it became very hard, then impossible, to cross the Israeli border into Gaza. During a visit over a decade later, Nasser Atta, a journalist, attempted to get me permission to cross in as he drove me south-west in his four-wheel drive. On the speaker phone he called a colleague in Gaza City, who picked up but sounded groggy. “What, sleeping on job, Omar?” Nasser joked. We heard static and the movement of Omar as he gathered himself together. “Of course not,” snapped Omar, not missing a beat, “how can I sleep with Jerusalem occupied?” He went on to say that permission to enter Gaza would be impossible to obtain.

Three years ago, I found Laila, or rather her brother Salah found me, through Facebook. Laila and I spoke for hours, and saw each other smiling broadly, Laila now wearing a headscarf and me with darker, shorter hair, as she noted. She spoke of India, where she had lived for years to pursue graduate studies in engineering, and she now works in a Gaza ministry. We were so happy to find one another, and she invited me to visit her as I used to, explaining with her brother how I could be safely smuggled from Egypt through the tunnels (dug out after the Israeli blockade to smuggle in food and medical supplies). I did think about it, and then reminded myself that I have two children and could not get myself stuck in Rafah. We promised each other that we would meet again soon.

Gaza during our Birzeit University days reminded me of Egypt. And some houses in the Rimal neighborhood, like that of Manal Nabulsi’s family, reminded me of the antebellum South with their wrap-around wooden porch we all sat on to catch a breeze.

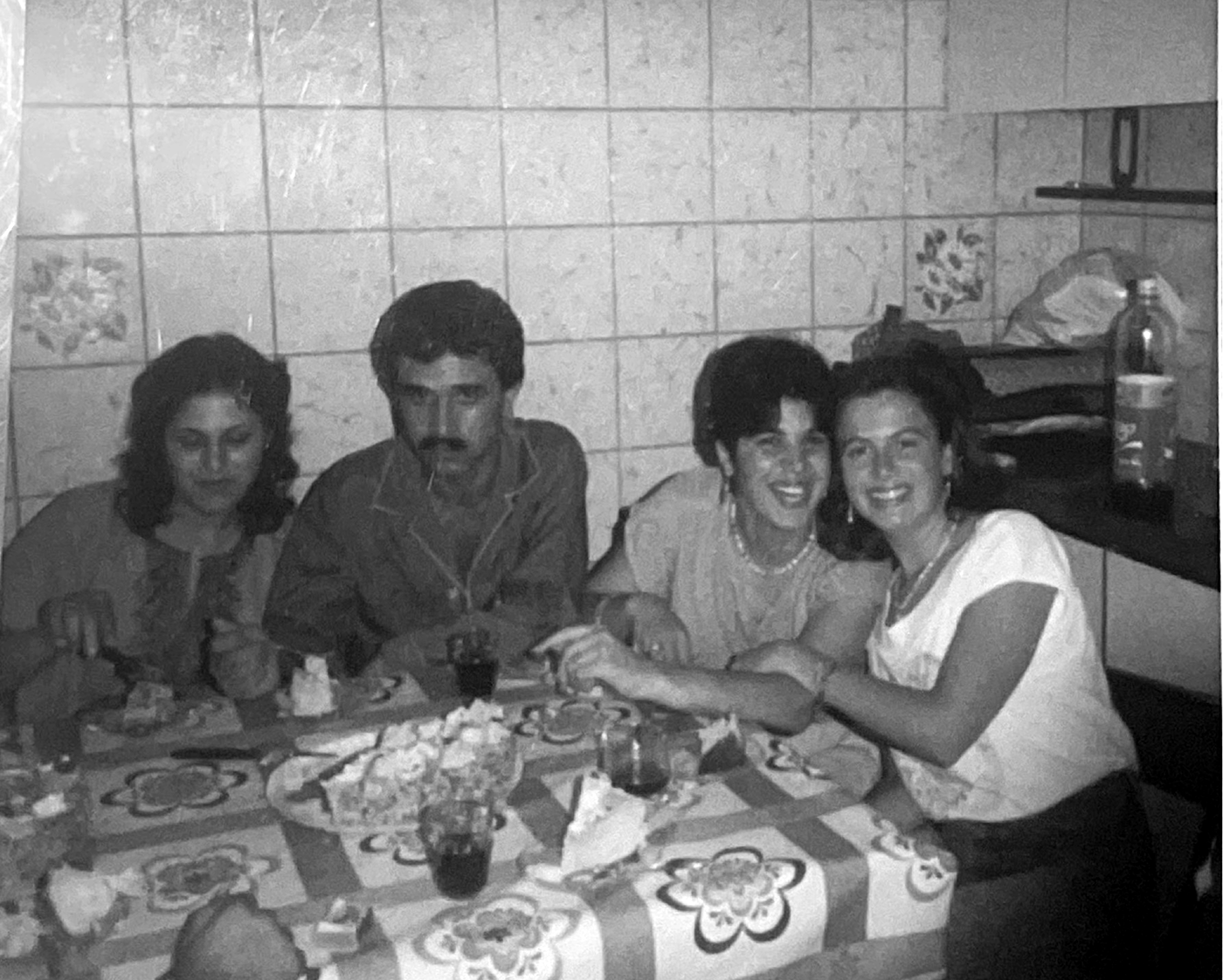

My best friend Rula Abu Kishk, a Palestinian Israeli from Nazareth and Lydda, who was my classmate since age 13 in the Friends Schools in Ramallah, took me along to spend the weekend at Manal’s house, her classmate from Birzeit’s engineering school. We sat on the floor of the porch with Manal’s sister-in-law Ayan who had just given birth, laughing, talking, cracking open almonds and eating them until her milk flowed down her dress. We stayed put on the porch floor to eat lunch, shaded by the overhanging garden trees. We spooned rice and hot soupy green slimy mloukhiyyeh into our mouths, our second hand cupped under our chins with each bite. With the generous amount of hot peppers cooked in, we all sweated at first, then I felt numb from the neck up but did not stop eating it was so delicious. Later we walked in the sleepy, dusty, hot marketplace to see the vegetables and marvel at a slaughtered camel hanging outside the butcher’s shop, a bouquet of parsley extending out of its emptied stomach cavity, and to survey store windows. We made our way back to Manal’s house to laze on the porch, talk and laugh some more before evening.

Nothing remarkable happened, just togetherness with Manal’s warm family. Inside her house I was reminded even more strongly of Cairo (I traveled from Jerusalem by bus to cross the El-3arish border every three months to renew my tourist visa, never knowing if the Israelis would let me back in) by the fanciful décor, full curtains over windows and walls, stately furniture, a big kitchen and dining table, airy bedrooms also amply decorated with drapes and coverings.

The everydayness of visits to friends in Gaza contrasted with my first trips there with my family as a child in the 1970s and early 1980s, also with university people. We went to swim at the beach in small groups, and I have no memories of visiting friends in town. At Gaza beach we were in fact visiting the beginning of time, passing the day in a world of three raw elements: sand, sea and sky and nothing else as far as we could see. Well, nothing else but us visitors, and an occasional clutch of young boys who emerged from behind the dunes descending to the beach, smiling widely at one another and at our foreignness in swimsuits. “Hello, hello, hello!”

Most of our Gaza beach days were naked, not just our bare limbs and torsos but the stark world around us. I can still see my brother and I at the water’s edge, with no shelter or parasol, and we would wade into the sea to escape the harshness of the sun. It was so empty and primordial a seascape that my sun-dyed hair, tanned skin, fine blond fur on my arms and thighs, my brother’s long dark curls, his squinting green eyes framed with curtain-thick lashes (like those of camels, to protect from sand and sun, as my mother pointed out), took on a painterly clarity, so vivid against the frothy waves and sand and sky that I could not stop marveling at our parts. We, the sand, sky, and sea seemed like all there was in the world.

Today Gaza’s sea ends at 9 kilometers, the limit set by the Israelis. What does this look like when you stare out to sea? If not a clearly demarcated watery border, everyone in Gaza knows the sea ends at that invisible point where people’s lives could end too, policed by Israel’s Navy, if their fishing boats venture further out. The small plot of sea is overfished and depleted to feed a malnourished and hungry people, like the Israeli occupied fields in the West Bank that cannot be left to go fallow some years, to enrich the soil, lest the Israelis use this as “legal” justification to confiscate “abandoned,” untilled land.

The Israelis are now intimately connected with us Palestinians on this beautiful and poignant land that is historic Palestine. Were the Israelis to succeed in their plan to drive all Palestinians into exile, keeping only a small number of us to call “Bedouins,” “Arabs,” and “Muslims,” as folkloric décor, say, or as proof of diversity, Israel is still not an island and is not part of Europe. It is a tiny piece of land that is part of a large, diverse continent including Arabs, Kurds and the Amazigh (Berber) peoples — a diversity that historically includes Jews. Hence, continuingas a bellicose, besieged country cannot be a good idea in the long term. It is in fact unworkable.The only way to ensure peace for all in this region is through the integration of the peoples and land of Palestine through reparations, equal rights, and justice.

I am one of those who finds your publication balanced informative, very thought-provoking and incredibably intellectually enriching for those of us who have (so far) not been able to explore that world first hand. I write this note not for publication please, but as a heart felt thank you to you, your writers, editors, researchers, for their valuable hard work. With much appreciation and thanks for what you do for those oof us not positioned to know without people like you working their asses off.

Again, not for printing. Just so that YOU know. Very, very sincerely and with humility.

Life in Gaza is simple and beautiful. I wish I could go back for a moment so I could breathe freely