Over 150,000 Londoners marched to stop the war on Gaza in 2014 (AP file photo).

Excerpted from Ramzy Baroud’s The Last Earth, a Palestinian Story (Pluto Press 2018), this is the account of an American named Joe Catron who went to Gaza by choice. Writes Baroud, “He was not a refugee, but what is a refugee anyway? It is true, he fled towards war, and not from it. But he was pushed forward by his fears, guilt, and a sense of purpose. Maybe a sense of not fitting into the world one is born into, or liking the game one is forced to play, made him a refugee to a certain degree, and perhaps he still is one. Maybe exile can be a self-imposed act of volition. Maybe Joe’s last earth is never meant to be found.”

Ramzy Baroud

The Last Earth, A Palestinian Story from Pluto Press.

His eyes were agape as he scrutinized his surroundings from wall to wall. Rest is not a luxury one can indulge during times of war. You have to face the danger and welcome moments of calm when they come. This takes its toll no matter how strong or resilient one is, but the Gazans certainly know how to put on a strong face, especially for an outsider. Dignity is everything. And even when you can take a break, the mind takes you on journeys that nothing could have prepared you for, no matter what you packed in your suitcase or what you might have read on a blog; or what books you might have devoured from the icons of Palestinian history. Nothing can substitute for actually living in Gaza. It is true, no one who goes is completely selfless and everyone has different reasons to be there, whether they talk about them or not, or whether they even know it themselves. Maybe one feels more alive there than in some New York coffee shop.

For Joe, Gaza was real and he was as present there as he could possibly be, doing what he believed was right. Whenever he attempted to close his eyes to regain some energy in something resembling sleep, not a moment later they would be wide open. Even though he had not slept for days, his worry was too intense to brush aside and his fears were multiplying by the minute. This place had changed him more than he had anticipated, and his perception of death had also changed: a fear that he had inherited from some distant past was forever cured. But this pace, this miserable, poor, alien, inspiring, besieged, disfigured, magnificent place, where columns of smoke rose from every square mile of landscape, had only swapped his fear of death with the guilt of surviving when so many he cared for were dying or being maimed all around him.

What kind of life was that anyway? And what if they all did die, every single one of them; the Swedes, the Venezuelans, the Americans, the Italians, the Palestinian doctors and nurses, and all the patients? What anguish would it be if they all died and yet he remained alive and all alone? How could he justify this scenario to anyone, but more importantly to himself? If they could not be saved, the volunteer human shield should die too. He should be the first to fall, in the line of duty; at least that is the logic he could accept and live with.

He closed his eyes once more, but again he was forced to open them. It was not the sounds of explosions that demanded his attention, but his thoughts laced with compounded fears and apprehension. He tried to distract himself and keep busy, and resist his solitude by calling friends in faraway places. An exhausted Gaza was falling all around while the world’s so-called peacemakers spewed their usual spiel of diplomatic chatter. The sounds of the city that he eventually grew familiar with—market vendors hawking their wares to customers; bargain hunters demanding higher discounts; cab drivers announcing destinations to random passersby; the laughter of school children and the routine calls for prayer — were replaced by the deafening noises of bombs dropping, whistles from missiles being launched from the sea, screams of pain from bodies trapped in coffins of rubble, whimpers of the dying on the verge of taking their last breaths, and shouts from hospital staff when ambulances would arrive as they carried limbless and stunned civilians.

“Wake up, Joe. Just wake up.” A voice bellowed through his head and startled him into an all-systems-go position. He hoped that none of it was real, but it was as real as the heart pumping rapidly in his chest. He had lived through this nightmare before, during the war of 2012, but back then he did not yet possess the awareness of its implications. As soon as the Israeli army named the offensive Operation Pillar of Defense, scores of people began falling in a calamitous war that once again did not distinguish between military targets and civilians. An entire family was claimed when a bomb blew out their whole building without the slightest warning. By the time the flames were extinguished in that cruel November, hundreds had perished in the war on Gaza with its beguiling name that echoed in mainstream media propaganda. While Gaza’s graveyards expanded in various directions as people scrambled to bury their dead, to Joe’s astonishment Gazans were still grateful that the number of casualties was not as high as that of the previous war. They all kneeled down and prayed for their martyrs before burying them and hanging up photos of men and women across Gaza’s streets. It was a bid to keep their smiling faces alive just a little bit longer, before the elements beckoned the evanescent visual poems back to ashes. And the faces of inculpable dead children were immortalized in graffiti tributes atop somber gray walls throughout the refugee camps, reminding all who saw them how life can betray you. The following morning, they began crushing the destroyed concrete remnants of collapsed buildings, turning the gravel and grit into bricks, trying to rebuild the homes, schools and clinics that were demolished. The task was great if not impossible because Gaza was still recuperating and under reconstruction after thousands of homes were destroyed in the war a few years earlier, deemed Operation Cast Lead by the Israelis. The destruction was happening at a much faster rate than the reconstruction; yet somehow Gazans ignored this and kept on fighting — weary and angry, but steadfast as ever.

Gazans are a unique people, unmatched in their kindness and spirit of rebellion — at least that is how they struck Joe Catron when he first arrived in the Strip in the early months of 2011. He came to stay for a couple of days that somehow turned into a few years. Gazans were full of contradictions. They wept for their dead for hours, but carried on with life full of faith that things would without a doubt someday get better. They spent much time in their mosques, praying more than the compulsory five times a day, seeking God’s forgiveness from sins they had never even committed. And they hardly ceased moving despite the confines that obliged them such limited access to the outside world, rightly earning Gaza the designation of being “the world’s largest open-air prison.” Two million people in perpetual motion, in a place measuring less than 365 square kilometers. Gazans were loud, often enraged by the slightest irritant; they were also quick to forgive and did not stew in jaded resentment. They kissed and hugged and smoked, and made children, and then went to sleep with a last prayer in case they never woke up.

Joe survived the war of 2012 and recorded some stories of those who had survived that onslaught and previous wars as well. But he never fully embraced war as a fact of life until July 2014, when its most unconstrained manifestations became real for him. From his arrival to Gaza in 2011, after crossing through the Rafah–Egypt border, until the start of the 2014 war, day by day he slowly began to understand a new set of unwritten rules. Learning through observation, and with his own origins in conservative America, he was able to navigate the cultural differences easily by comparison to some fellow activists, and was sometimes even mistaken for a Palestinian himself. Adopting both good and bad habits and characteristic rituals, he walked everywhere and greeted everyone he encountered; smoked incessantly; spoke about everything from politics to Jinn, from poetry and love to the contradictions of the sea (offering a possibility of escape while simultaneously being part of their prison), to the meaning of life and death.

Maybe all this was the perfect training ground for the ultimate test of July 2014. The Israelis called their new war Operation Protective Edge, but it was Gaza that needed protection and Joe felt compelled to do something, anything. Gaza had been under a strict siege for years. As a consequence, in order to push back the invaders, local fighters collected their own weapons as well as improvised bombs and rockets. They dug tunnels because the earth below offered the only protection, though there was also within them the risk of suffocation or flooding; through them food, flour, toys, and cement, as well as rudimentary rocket launchers, were channeled across deserts and borders. And when tunnels crumbled and the bodies of those who had dug them could not be retrieved, Gazans would carry out symbolic funerals, chant for the martyrs who remained underground, vow to fight, and then dig more tunnels. There was no alternative for Gazans, it was either that or bow down to the occupier. Joe of course did not have to be a part of all this, he had a choice. When the air strikes began in early July, he could have run away and no one would have ever chastised him for it. In fact, others did leave. Many internationals rushed to the Rafah border and beseeched unsympathetic Egyptian guards to let them into Sinai so that they could go home from there. But Joe begged no one, remaining in Gaza not to dig tunnels, but to explain to the world why Palestinians had to build them.

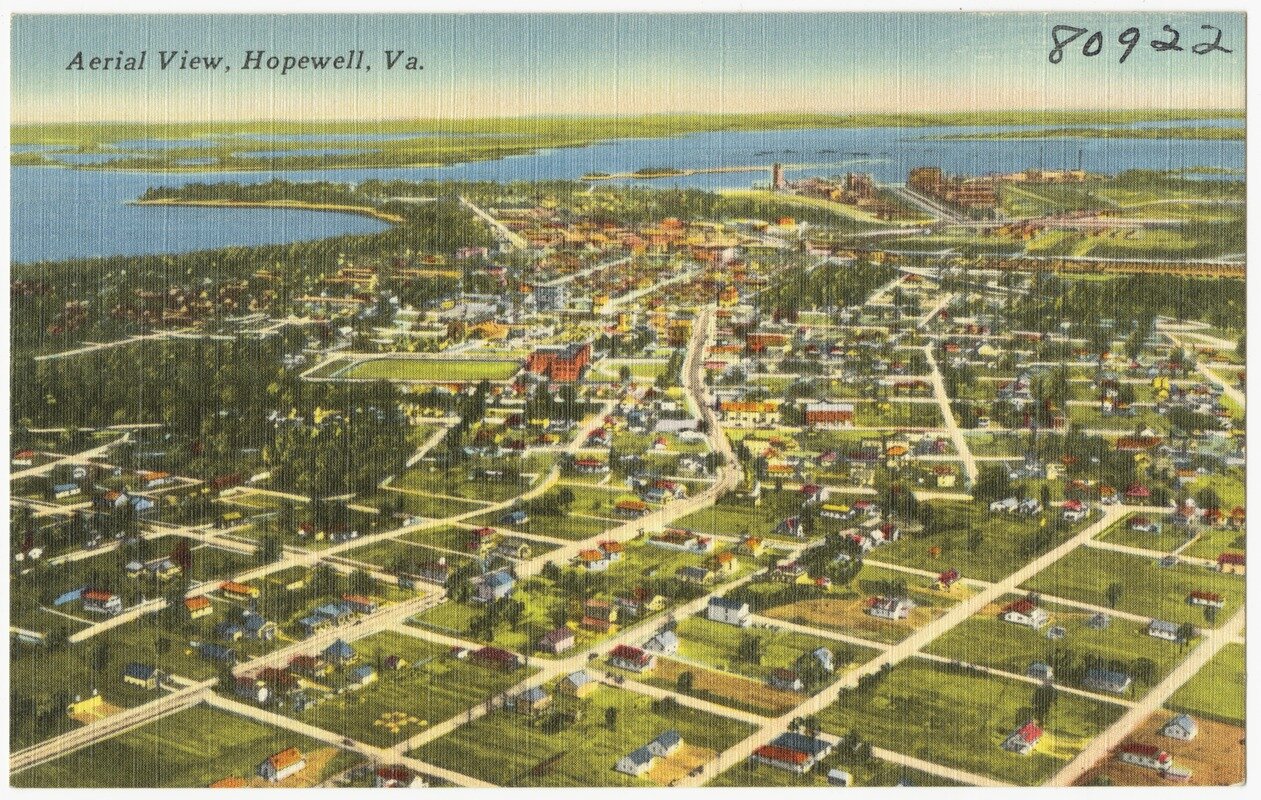

Vintage postcard with an aerial view of Hopewell, Virginia.

Gaza was very different from Hopewell, Virginia. The latter was an industrial town, bereft of the lights and noise of big cities, but it was good enough for Joe. His house comprised one floor with three bedrooms, and it was nestled near the converging point of two railroad lines that served the chemical factories of the town. Childhood for him was a long, uninterrupted bike ride upon a dirt road. The path was an unfinished project left to the whims of young kids who reveled in its simplicity, free from the confines of middle-class play dates in safe environments that offered little risk of scabbed knees. The city planners ran out of money, or for whatever reason lost interest in the road. This was good news for Joe and the other neighborhood kids as the dirt road was connected to a seemingly infinite grassy field. Both the road and the meadow were a child’s heaven. One day, though, he left it all behind. Compelled by a curiosity stronger than himself, he chose Gaza. It was not the last earth to which Joe would travel, but it was the most vivid physical and emotional contrast that could be imagined for a child from Hopewell.

Joe could have rushed back to Hopewell, Virginia, as soon as the children stopped screaming and the evening news repeated the final death toll and announced that the war was over. He could have packed his bags and left his little flat near the Gaza port, and gone home to the mother he had not seen in years. Barbara would surely have taken a day off from driving her cab across Virginia, come and greeted him at the airport, bringing him a gift or at least wearing a proud smile. She would have certainly honored him for following his heart, and like any loving mother maybe would have admonished him for not visiting sooner. And he would have reminded her that it was because of her guidance that he learned to think for himself, to take risks and understand the world as it really was: unforgiving at times, but grand. He had never really had plans to leave Gaza in the first place, even after the bombs stopped falling, and the well over a thousand dead were counted and buried. He simply could not leave. Not yet. If he left, his guilt would have been a burden to carry for the rest of his life, and anyway he still did not understand why he had left Hopewell in the first place.

In one final attempt to fall asleep, Joe closed his eyes, but rest was out of reach. A bomb had shattered much of the building’s fourth floor, and it was Joe’s turn to speak to the reporters huddling in the basement of El-Wafa Hospital. They kept asking him: “Why is the army bombing a hospital?” And to that obvious question, he kept telling them again and again that he just did not know the answer.

— • —

It was Joe’s maternal grandparents, Homer and Barbara, who first got him thinking about the world outside Virginia. He had never seen his Dad, or perhaps he did once, but he was too young to remember. Joe’s father died many years ago, after he had abandoned the boy and his mother, leaving Joe with no memories that would give him a reason to love his father, or perhaps hate him. It was Homer instead who took the role of father figure in Joe’s life. Homer and Barbara were the products of the profound historical circumstances that had shaped them and by extension their whole family. They survived the Great Depression and were both swept up by the promise of “relief, recovery and reforms” as enunciated in President Roosevelt’s New Deal in the mid-1930s. Both of Joe’s grandparents had come from the Scotch-Irish highlands of Virginia’s Appalachia. There in the mountains, poverty was extremely dire and the painful memories were often repeated to young Joe as a reminder that his generation was a lucky one. In their final years, Homer and Barbara managed to realize their own modest version of the American Dream —having a home of their own, two cars and some money in the bank.

Yet they fought many battles to get there: a figurative war against poverty and want, and actual wars against whomever the United States deemed the enemy at the time.

Homer was a tank gunner on the front lines of what was referred to as the “European theater”; a war that saw the destruction and rebirth of Western civilizations. Then, sometime in 1940, he joined the Army Air Corps only months before it was rebranded to become the US Army Air Forces (until 1945). Joe never had a clear understanding of his grandfather’s politics early on, but many signs indicated that Homer had fought enough to eventually loathe war completely. When teenaged Joe began expressing his desire to join the army, deterring him seemed to become Homer’s main mission in life. Homer eventually prevailed, changing the course of Joe’s life forever. Homer had always regretted his own lack of education. During his youth, education was considered less significant while surviving poverty and war were the nation’s top priorities. He struggled to read newspapers, while Barbara read novels; and when he opened the papers every morning, the disquiet caused by his handicap was visible on his face. By the end of his life, Homer had declared himself a socialist, implanting a thrilling idea in Joe’s head: that when socialism would one day prevail, as it had to, all of the world’s political systems would be transformed from those that ensured the dominion of the rich over the poor, to those in which infinite possibilities of social justice and equality were more than just the wishful thinking of an aging ex-soldier.

It was Joe’s mother, Barbara, named after her own mother, who helped Joe translate his new desire for change in the world into intelligently articulated language. She loved books and subscribed to several magazines, those offering political commentary, but especially fine photography. She encouraged Joe to read and engaged him in endless discussions about right and wrong, morality and ideology, and how to live a meaningful life. Born in 1954 during the baby boom years, old enough to understand that American wars were taking on a more covert and sinister character, Barbara was at the forefront of societal dissent. A degree in mathematical science, rooted in structure and rules, did not make her a conformist in the least. She hated compliance, particularly the kind that was typical of the dreary, uneventful existence of the class known as white collars. Instead, she finished university and after trying various career paths, she found driving a cab most to her liking. Barbara’s personal history taught her to be strong. She lost her only brother to a car accident when he was in his early 20s, and one of her three sisters drowned. Left with Marie and Ava, who also faced their own struggles, she carried on with a smile on her face.

Conflicts in the Middle East were staples of the news consumed in many American households. These viewers were informed, one generation after the next, of Israel’s righteous battle against hordes of encroaching Arabs. The Catron family did not fall prey to this propaganda. They knew how to read between the lines, having been influenced by a self-declared socialist grandpa, and a younger generation that grew to distrust the official version of everything. They knew the truth was quite different than what was presented on the evening news. Ava had joined her husband while he worked for Aramco in Saudi Arabia, where they lived in an expat compound. Whenever she came home to visit, her sympathies for the Palestinians and the reasons for them were eagerly communicated to the family. After she separated from her husband, Clint, and finally moved back to Virginia, much time was spent conversing with Barbara and a very curious Joe.

Then there was Keith, who along with Joe was a fixture at Hopewell’s local library. Through their long conversations, Joe’s politics took yet another leap far away from the mainstream thinking of what was acceptable in his town, indeed his entire country. Keith, in his thirties, bespectacled with short curly hair and a handsome face, was an advocate of a curious blend of Marxism-Leninism and Black Nationali

sm. It was only later in life that Joe questioned whether Keith’s variations of the two revolutionary brands were compatible, but without a doubt Keith’s enthusiasm galvanized Joe and their days became a prolonged, unsolvable argument. Between his work as a union activist and postal worker, Keith read voraciously on a wide range of topics while Joe was still a student trying to form his own unique political identity, with no practical experience to help him differentiate between achievable goals and wishful thinking. Eventually Joe decided to delve further into the world of fiction when he designed his own major at The College of William & Mary, studying Folklore and Mythology. Joe’s interest in the supernatural was not new. He had spent much of his young life seeking solace in fantasy novels and as a young teenager tried to write his own. Sure, they were mostly a child’s adaptations of widely available fantasy books, the Lord of the Rings trilogy in particular, but he did labor to breathe his own identity into them; his character, hopes, dreams, and fears as well.

During this exploratory time, Joe remained concerned with the real world around him. What troubled him most during those years was how to achieve actual, definite, and tangible change in society. He joined every group that purported to offer progressive politics, looking for an answer. The anti-globalization movement was particularly attractive, for it claimed to offer a global context to everything that had gone wrong in the world. From a distance, it seemed to be the ideological extension of all the anti-war movements that had thrived during America’s dirty wars in Vietnam and the rest of Indochina. As Joe drew closer to the global justice movement, however, it became less appealing because of what he saw as the lack of an effective plan of action or even a serious attempt at building one.

He still marched in every rally he could, and took every opportunity to exhibit his placards chastizing one American foreign policy or another. But the causes the movement backed seemed too numerous, the costumes too frivolous, and the signs ill-considered. It was more like an activist circus than an actual platform through which a coveted paradigm shift could be achieved. It was a strange mix of people supporting causes that seemed rarely to overlap. Back then Joe argued that those who did not take themselves seriously were unlikely to convince anyone else of the seriousness of their cause, but he had no other option but to keep on marching, rallying, chanting, and demanding one form of justice or another. Deep down the urgency to do something more tangible grew.

It was not until Israeli tanks rolled once more into Gaza in 2008, declaring war against the besieged inhabitants of the Strip, that Joe found his calling. That was still a few years before he actually crossed the Atlantic and then the Mediterranean to finally cross the Sinai Desert into Gaza, and found himself a de facto spokesperson for El-Wafa Hospital days before it was leveled to the ground. He was angry at the plight of all of those dead children and furious at his own government for defending and arming their murderers. So, one morning Joe folded his most trusty placard, put on his favorite kufiyah, and took the subway to Manhattan to join an anti-war protest called by the Palestinian community in New York. As he reached his destination, he found himself in a whole different world of activism. It was an entire community wearing kufiyahs and flooding the streets of New York City in a sea of emotions, an abundance of tears, and a single chant that was so focused and penetrating that it left the young Hopewell activist in reverence. “Free Free Palestine,” “Free Free Palestine,” they all cried, delineating over and over again this overriding priority of a mobilized community. It was invigorating. Joe was not asked to conform to any particular ideology, or expected to declare allegiance to a precise line of politics. All that was required was a kufiyah, which he was already wearing upon his shoulders, in order for him to merge seamlessly into the burgeoning mass of scarves and flags, whether in Brooklyn, Bay Ridge, or Manhattan. It was a massive community where neither color, nor gender, nor class mattered; the important thing was being unified around one cause with distinct demands for freedom, justice, and an end to a war that had already taken the lives of hundreds. “Free Free Palestine,” he shouted along, his voice unique, but also a mere echo within the thousands of other voices. This time the words had an authentic taste and he grew even more determined to bring about this change himself.

— • —

He carried on chanting even louder, but soon he was actually in Gaza. When he arrived, his first self-assigned chore was to hold a placard that he had designed himself and squat alongside a group of mothers demanding freedom for their sons and daughters in Israeli jails. It became a custom Joe looked forward to every week as part of his humble Gazan life. Most Mondays for years, in front of the Red Cross building in the heart of the Remal neighborhood in Gaza City, Joe would be there to support their cause. The mothers had been gathering in that same spot for years before Joe had joined them, but once he did, he became a permanent companion of the griefstricken women, and later of other supporters and family members who were also separated from spouses and children without any news for years at a time. The Red Cross building would also be the backdrop for the twelve-day hunger strike in which Joe later partook along with two other international activists, in solidarity with the mass hunger strike of Palestinians in Israeli jails protesting against their inhuman conditions.

It was the happiest day of his life when 477 prisoners were freed in a prisoner exchange that saw the largest and most clamorous celebrations that Joe had ever witnessed. Not only did he experience total exhilaration, but he felt like he had contributed to something much bigger than himself.

More tasks were added to Joe’s schedule, which grew busier by the day. He tried to teach himself Arabic, and whatever he could not communicate using his limited vocabulary, he attempted to convey using facial expressions, mostly those of sympathy and solidarity, but also of amusement and felicity. The rest of his days were spent meeting people and walking around refugee camps where he was repeatedly mistaken for a refugee himself. His fairly dark skin and unassuming demeanor obscured his ethnic roots and evinced an air of familiarity, so he was often approached by people who would speak to him in a rough Gazan accent, and he would smile. “Ana ajnabi,” he would say. Some would question if he was indeed a foreigner, for he dressed in familiar humble attire and did not walk around brandishing cameras or electronics as other foreigners typically did. He did not drive around the scruffy streets of the refugee camps with a new car dotted with foreign lettering, and did not have a “fixer.” Instead he had friends who were mostly refugees, and who eventually began to see him as one of them. Joe tried to integrate as best he could and find his place in Gaza as if he were a Palestinian, not an outsider with one agenda or another. In time, Gaza had become his new Hopewell and he was just fine with that. Of course, this new Hopewell was very different — it was welcoming and beaming with life, yet it was also teeming with great danger.

Joe was not in Gaza as a thrillseeker looking for his next fix, and hated it when the international press wanted to make the story about him rather than focusing on the Palestinians. This predicament presented itself often to him and other activists who felt a moral obligation to be in Palestine. But what was he to do? Risk not telling the story, or not have the story told at all? How could this norm be dismantled? This paradox had to be ignored to a certain extent, as the dynamics of racism and colonialism regarding media coverage was too big of a beast for him t

o decipher. So, he put his efforts into his daily tasks. He accompanied refugee protesters to the northern Gaza borders where the towns of Beit Hanoun and Beit Lahia were separated from southern Israeli towns by an army that opened fire whenever a kid raised a flag or a farmer ventured on to his own land. It was through these northern towns that Palestinian refugees crossed into Gaza in 1948, barefoot and bewildered. Many of the youth that Joe accompanied to the heavily militarized zone came from a village or a town that either still existed under a new designation, often a Hebrew name, or had been entirely erased from the map. Their fathers and forefathers had made Gaza their temporary home and were told that returning to Palestine was only a matter of time. They all fought hard to speed up that return, but to no avail. So, their children kept on returning to that very border, gathering at the fences of what was once their country, chanting, “Free Free Palestine,” and Joe would chant along.

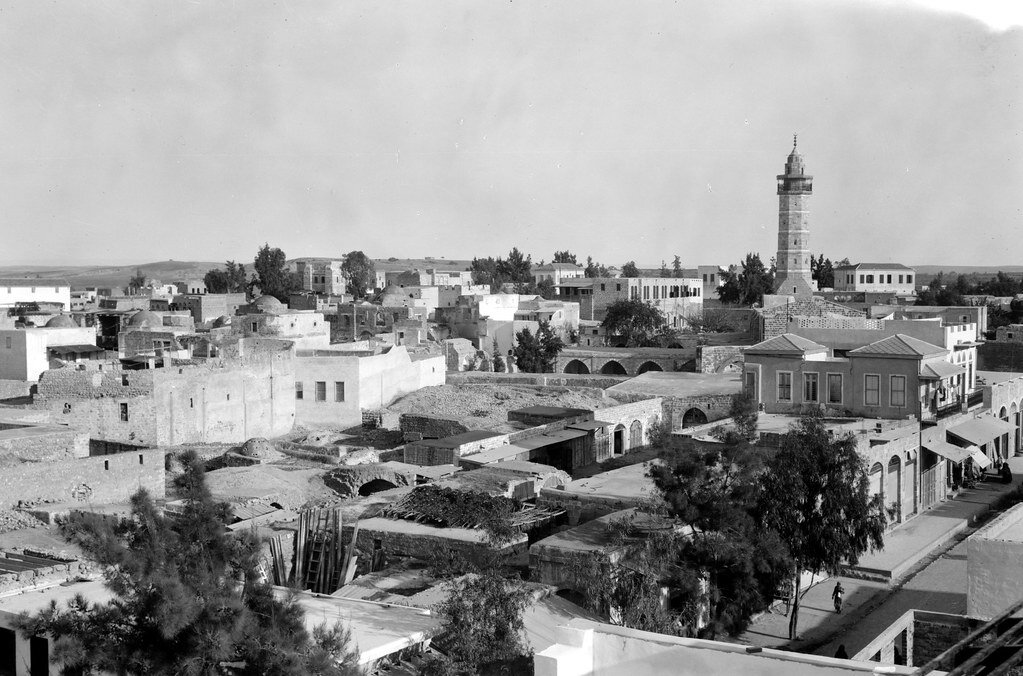

Gaza pictured in the early 1940s.

Gaza had changed since 1948. Nearly 200,000 refugees fled for their lives at that time, escaping massacres and systematic destruction of dozens of towns and hundreds of villages. After that, the Strip was ruled by Egypt, and following the latter’s defeat in 1967, it was overrun by the Israeli military and armed Jewish settlers who claimed their own beaches and used much of the water for their massive fortified settlements, industrial lakes, mango farms and swimming pools. As the colonies expanded, the refugee camps diminished in size. Even after the Israeli army evacuated its colonies, deployed its forces to border areas, and besieged the Gaza Sea in 2005, Gaza still continued to shrink. For one, its population had grown to nearly two million, but also its most arable lands that adjoined the Israeli border were declared military zones. Not far away from what became a death zone, snipers took their positions above reinforced watchtowers. Even the sea was beleaguered by the Israeli Navy, which instructed Gaza’s fishermen to venture no further than six nautical miles from shore, which was then reduced to three, compounding the issue further as fish would be difficult to find in the shallower waters. And whenever it suited their twisted whims, they blew the small Gaza dinghies out of the water and watched the survivors swim back to shore. Joe had even accompanied some of these fishermen and no matter how much he screamed at the military boats that he was an American and they should leave the poor fishermen alone, they seemed to care little for him or the international laws they were breaking. Their faces were stiff, their guns mounted and ready to fire, and not even Joe Catron of Hopewell, Virginia, was capable of changing the dynamics of that disproportionate war.

Joe’s stay in Gaza was initially meant to last only a few days. But something impelled him to remain. The internationals in Gaza were not many. Some were affiliated with NGOs that had managed to carry on with their operations despite the siege imposed on the Strip by Israel and the Egyptians as early as 2006. Others were activists like Joe, although each had different reasons to be there. There was the rich English kid who walked around Gaza as if he were a savior of the miserable multitudes; and there was also the older small-town American woman who chastised Gazans for fighting back, preaching to them the nonviolent teachings of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King. And, of course, there were the many journalists who would stay in Gaza for a few days or weeks only to return to their countries to write thorough investigations or even books about everything the world needed to know about Gaza’s militants, underground tunnels, and history of political movements. But there were also the unpretentious ones who knew that by the end of their journeys they would have learned more about themselves than they could ever possibly have taught Gazans about life, survival, and resistance. Joe was one, but there was also Vittorio Arrigoni, the man who had proudly tattooed on his right arm the word “Al-Muqawama” — Arabic for “Resistance.”

El-Wafa before it was bombed and destroyed in 2014

Vittorio was murdered soon after Joe had met him. He had anticipated becoming friends with the Italian, who at times seemed to physically resemble Che Guevara. But Vittorio was kidnapped by a Jordanian and some Gazans and later found dead in circumstances many regarded as mysterious. Palestinians wept for Vittorio as if he were one of their own, just as they had wept for Rachel Corrie before him when she was repeatedly run over by an Israeli army bulldozer, and Tom Hurndall, who was shot in the head by the occupying army. The Palestinians called them martyrs and inscribed their names and pictures all across the refugee camps. Vittorio, unlike Rachel and Tom, was killed by Gazans with whom he had come to declare solidarity. He arrived in Gaza in 2008 atop a small boat that carried a group of activists challenging the Israeli siege, and acted as a human shield during Operation Cast Lead. Vittorio befriended hundreds of people and with time became a popular fixture in most of Gaza’s activities, conferences, protests, and many celebrations. In addition to his solidarity work on the ground, he also wrote books, articles, and entries on his blog Guerrilla Radio when he was not protecting farmers and fisherman. Joe and Vittorio spent little time together before his tragic end. They first met at a café in the university district in Gaza, but the last time Joe saw Vittorio alive was at a party on the roof of Joe’s apartment building in Gaza City. That night Vittorio was quiet and reflective, with little to say, perhaps lost in his own thoughts.

It was not the impression that Vittorio had left on Joe that lingered the most. It was the shock and pain of his death that lived on. Gaza’s small community of activists from around the world sought comfort in each other’s company. So, when a friend, who had risked his own life for Gaza, was killed in peculiar circumstances, the pain was mixed with confusion, as Vittorio’s motto “Stay Human” reverberated across the world.

Joe and Vittorio’s time in Gaza overlapped by only a month. Joe had been with the International Solidarity Movement for about a week when this baptism by fire took place. The ISM was a group of internationals who stayed in Palestine for various lengths of time, each with his own spin on solidarity and direct action. Before Joe arrived, death was hovering over Gaza and his coming changed little in the course of bloody events. Operation Returning Echo in March 2012 was a crash course in the punishment Gaza had been subjected to for all of those years. “Only” scores were killed then, but it was a taste of what Joe and all of Gaza would experience in November of the same year, when hundreds perished under the rubble of their homes as they took shelter in schools, or even in their hospital beds when seeking medical care.

In November 2012, Joe’s trial of guilt began. He had not felt useful during that war. Mere words of solidarity seemed frivolous when graveyards were swelled with corpses of whole families. That war left Joe with a dilemma that persisted for months. He could either dwell on his fear of death or do what had to be done—more importantly, what was expected of him and what he expected of himself. He chose the latter course, and then the 2014 war began.

— • —

El Wafa Medical Rehabilitation Hospital in ruins after 2014’s “Operation Protective Edge.”

The relatively large El-Wafa Medical Rehabilitation Hospital was bombarded for days on end. It was mostly empty. The majority of its patients had already been evacuated, but fourteen remained because their conditions were too critical. Attached to machines keeping them alive, any attempt at relocating them was likely to endanger their already vulnerable lives. The logic was perplexing. Basman Alashi, the executive director of the Al-Wafa Charitable Society responsible for running the hospital, had appealed to Joe and a few other internationals to come and to invite international media to see for themselves that the hospital stored no arms and that no rocket launchers were mounted anywhere within its facilities. Joe obliged, not only for the obvious humanitarian and ethical reasons, but also because of his profound respect for Basman Alashi. Joe and the other activists were certain that the Israelis knew without a doubt that El-Wafa was not a base for Hamas or any other local resistance group. And he was going to prove this, showing to the world and himself that the time had finally come when he would overcome all of his fears.

El-Wafa was located at the eastern end of Gaza’s main commercial street, Omar al-Mukhtar, in the Shujaya neighborhood. The location was convenient when patients needed to be transported from nearby clinics and hospitals for urgent care, but when Israel launched Operation Protective Edge in July 2014, El-Wafa’s strategic address proved to be a curse. Only meters away from its main gate stood a large separation barrier that divided Gaza from a military zone at Israel’s southern borders, making the hospital a position that could potentially benefit their long-term strategy. From an Israeli military viewpoint, it needed to be conquered, no matter the price. For Joe, this was a critical moment. Refusing to be stationed in a hospital-turned-military-target was to betray the very essence of his journey to make the world a better place whatever the risk. He answered the call, serving shifts of twelve hours at a time, along with other activists like the Swede Charlie Andreasson, who also was trying to resolve his own moral dilemmas.

Journalists had gathered together so that Joe and Charlie could inform them of their decision to serve as human shields to safeguard the critically ill patients and the hospital staff. But the presence of international activists barely changed the scene in any way. The day before Joe arrived, four small Israeli “warning rockets” slammed into the hospital’s roof and walls. In the afternoon of Joe’s first day on the job, a large missile struck the fourth floor, leaving a gaping hole, shattering many windows and unhinging many doors. A massive Israeli strike seemed imminent, regardless of the fact that patients could not be evacuated nor could the staff leave them there alone.

Elsewhere in the Strip the casualties were mounting. The horrors of the war were unprecedented even by Gaza’s grim norms. Over fifty entire families perished in a matter of weeks, in every part of the Gaza Strip, especially in the northern neighborhoods where Israeli tanks attempted to advance but failed due to stiff local resistance. Hundreds of fighters were trapped in the tunnels which they used to combat the advancing soldiers. Airstrikes never ceased; thousands of flights were conducted in the sky above that tiny patch of earth that was Gaza. It seemed that everyone was on the target list: schools were demolished; over 20,000 homes were destroyed; twenty-four hospitals were damaged or fully razed; and half a million Gazans were on the run with nowhere to go because no place was safe or sacred. Even UN facilities, where nearly 300,000 refugees sought shelter, were targeted, sending the refugees on the run yet again. Even in this inferno, many opted to stay home without running water or electricity, and very little food. Prayer was abundant, because only God could help then.

Joe stayed too. He sincerely wanted to. He knew that Alashi had summoned him — not to die, but because as far as the Israelis were concerned, Palestinian blood was cheap. Though it was a long shot, the hope was that the presence of an American and a Swede might make the Israeli government pause and consider the consequences of its actions. The unity of the activists intensified along with Israeli threats against the hospital. The number of internationals there grew. Joe and Charlie were joined by an Australian, a Brit, a French national, a New Zealander, a Spaniard, and a Venezuelan. Days passed and missiles whistled by. The activists were prepared to die so that others would have a chance to live. And in that very moment, Joe Catron had stepped over the boundary that separated his old self, an activist with many questions and few answers, to his new self, a man, still with very few answers, but with a clear sense of a calling and a purpose.

Unlike the prolonged conversations between Joe and Keith back at the Hopewell Public Library, Joe’s conversations with the other internationals who gathered as human shields at El-Wafa Hospital were more lucid and far simpler. They bothered little with grand plans aimed at changing the world. There was no time or even desire to figure out whether national liberation movements could be streamlined into Marxist–Leninist theories within an anti-globalization platform that could effect a paradigm shift the world over. Their reflective and almost spiritual conversations at El-Wafa were focused largely on their determination to save lives, sacrificing their own if necessary. Eventually El-Wafa was entirely destroyed. A barrage of missiles struck on July 17, prompting a chaotic evacuation of all those inside. Other hospitals were also destroyed in the following days, and not even the presence of two Swedes at the Beit Hanoun Hospital spared its total ruin on July 25. Aware that their Western passports mattered little to the advancing army, Joe and his international companions still moved to serve as human shields elsewhere, this time at the largest Gaza hospital, Al-Shifa. There was no turning back once they had made their choices, notwithstanding what little affect their actions had. There still would have been the guilt of “What if?” haunting them had they not stuck to their ideals.

— • —

It was in late August that news of a looming ceasefire began to surface, though the sounds of the blasts which shattered many windows were telling another story as Joe filled his Twitter feed with the latest causality figures. His stint as a human shield at the Al-Shifa Hospital was less frightening than his days at El-Wafa. The explosions grew closer after midnight for some reason while he sat in the hospital’s library, not far away from the overflowing morgue. Yet the sounds of bombs never grew familiar to Joe’s ears. Each and every boom was accompanied by the same adrenaline rush and fear for his life. But he wanted to save others more than he wanted to save himself. Those who live through wars develop a range of psychological methods to pacify themselves, to survive the violence while maintaining their sanity. “Once you hear or feel a blast, you have already survived it,” is what Joe used to say to console himself and others when the bombs came closer.

Al-Shifa Hospital staff had already informed him and the others that even Gaza’s largest medical facility, far away from the combat zones, was no longer safe. In fact, when heavy explosives were unremittingly lobbed from the ground, sea, and air, all of Gaza became a combat zone from which there was no escape. Joe’s typical response to all of this was eventually reduced to “mashi,” accompanied with a nervous smile and a fading hope that the war would soon come to an end. The reality was totally opposite. There was nothing “fine” about it. And although the war carried on for much longer than anyone anticipated, fifty-one days, Joe never grew numb to the sight of bodies of mutilated children and women, or to the decomposed, agonized corpses coming to Al-Shifa morgue. He was so far from Hopew

ell and his days reading about astronomy and mythology. The two worlds were so different, and he struggled to make sense of it all.

In Gaza he learned to bridge cultural gaps because the presence of death teaches people to care more for one another than for themselves. When the survival of a whole group is at stake, the individual, although he still matters, becomes a secondary aspect of one’s unyielding fight for existence. The point is to save a collective being. Joe Catron not only reached that realization in the last days of the war, he internalized it as well. He never really abandoned his fears completely, but fear over his personal safety shifted to fear for that of others, changing Joe’s relationship with himself and the world. He could finally understand why war made a “socialist” out of Homer. The old man could hardly decipher the language of a newspaper, but it turned out that solidarity was not really conveyed through a written word, but through action.

Indeed, one aspect of Gaza’s culture that struck Joe as odd when he first arrived — to stay for a few days that turned into years — was how young people, the shebab, would often run towards explosions, not away from them. They did that to save those trapped under the rubble of some building or pull out the bodies of those whose flesh and bones were melted together in the burning metal of blown-up cars. Towards the end of his stay, he was doing the same thing, exactly what he once perceived as peculiar. Unlike many other, more sensible, foreigners, his instincts made him rush to rescue someone he had never met before or even knew existed, rather than run away to save himself. Whenever a ceasefire was declared, he found himself along with other internationals rummaging through the wreckage of destroyed neighborhoods, looking for trapped bodies. This led him back to Shujaya neighborhood when it was almost entirely destroyed, and hundreds of its residents were killed or trapped under the concrete of their homes. The Red Cross had by then suspended its operations in that area since the invading soldiers neither respected humanitarian ceasefires nor had any particular regard for ambulances with large red crosses on them.

It was then that Joe met Salem Shamaly, the archetypal Gazan teenage boy with short hair buzzed on both sides, skinny jeans and not fully developed facial hair. Salem was the only son in a family of seven sisters. He was somehow separated from his parents and siblings during the chaos. When a temporary truce was declared, he returned to a devastated Shujaya, walking hazily amid the rubble, yelling the names of his loved ones, unable to recognize his home or even his neighborhood. When he met Joe and his friends as they too looked for survivors, they tried to dissuade him from going any further, knowing that Israeli snipers were positioned atop the tall adjoining buildings of the neighborhood. He was desperate to find his family, and they agreed to join him in his search.

Joe Catron, a solidarity activist and freelance reporter, returned to New York from Gaza, Palestine, where he lived for three and a half years. He writes frequently for Electronic Intifada, Middle East Eye and Mint Press News, and co-edited The Prisoners’ Diaries: Palestinian Voices from the Israeli Gulag, an anthology of accounts by detainees freed in the 2011 prisoner exchange.

There were eight of them in total, seven internationals and Salem. Joe captured much of the undertaking with a camera, and the captured images would gnaw at him for probably the rest of his life. They decided to walk in two groups, crossing streets as quickly as they could so the snipers would have little time to shoot at them with their explosive bullets or reload their guns for another go. Salem either didn’t understand the plan or was eager to cross the once familiar roads once again. He crossed alone, just after Joe and three others ran to the opposite side of a dirt road, and just before they gestured for the others to follow their lead. It was a matter of seconds that determined it all. A single bullet struck Salem in his lower body. The young man, wearing a green t-shirt and carrying a cheap Nokia phone, remained conscious and expressed his pain through agonizing shrieks that echoed across the streets of the now destroyed Shujaya. He raised one arm to the snipers so that they would stop firing, but they did not heed this call for mercy. They fired a second bullet, and a third, and a fourth, and with each shot his voice faded, his body stiffened and eventually he ceased to move altogether. Joe and the others stood frozen by the horror of the moment. Nothing could have prepared them for this. When Salem’s body gave in and shells began to fall all around them, there was no other choice but to run back to relative safety, leaving Salem behind in that spot where he stayed motionless for several days until it was safer to retrieve his body.

Salem’s death, so quick and ferocious, the sight of him grasping his outdated Nokia and the sound of his voice crying the names of his seven sisters and parents, had an impact on Joe like no other experience he had had before in Gaza. The team of witnesses shared the videotape of the incident, recorded by Mohammed Abedullah, on every social media platform they knew of, aiming to compel the Israeli army to allow the evacuation of the teenager’s decomposing corpse. Salem’s family never dreamt that one day they would watch footage of their own flesh and blood leaving this earth in such a brutal way. It was one of his seven sisters who recognized him while viewing a YouTube video of what she expected to be some unnamed dying Gaza kid. Hearing his cries for her just made the experience all the more scathing. Salem did not deserve such a cruel final walk on his last earth. By the time she saw the video, before the final carnage, Salem’s sister had managed to escape from Shujaya along with the others and was deep in the heart of Gaza City.

“Gaza has a way of making you grow up in a hurry,” Joe wrote to a friend soon after he left Gaza. He quoted a poem of Mahmoud Darwish which he had read every single day during the 2014 onslaught.

Time there does not take children from childhood to old age, but rather makes them men in their first confrontation with the enemy. Time in Gaza is not relaxation, but storming the burning noon. Because in Gaza values are different, different, different…

Was Joe referring to Salem? To all the children who grew up underneath the ground, digging their own tunnels to freedom, only to end up fighting an impossible war and being buried under sand and water? Was he referring to himself, to that child from Hopewell, Virginia, who grew up without a dad and escaped his demons on a rickety bike over a dirt road that led to an infinite meadow? Some months after the war, he wrote with the cynicism and stubbornness of a true Gazan:

I’ve emerged more energized and determined to support Palestinian liberation than ever. This doubtlessly has something to do with basic human impulses: engaging with people and sharing their lives has a way of making you understand their motivations and goals more intuitively than you might otherwise.

Joe returned to New York a few months after the war ended. Once there, he rarely engaged in conversations about grand theories of social change. His experience in Gaza made him all the more engaged and focused, but at times also very cynical, the same syndrome that afflicts many Palestinians once they leave their homeland. This was especially true for Gazans, who fear being far away from home when the next onslaught comes. Joe’s worry for his friends in Gaza, who initially mistook him for a refugee, overwhelmed his thoughts. That small strip of land, a microcosm for all the conflicts burdening our imperfect planet, would stay with him forever. His relationship to it was now that of true devotion to a brother, or a family. In fact, Joe’s feelings were not all that different from Salem’s when he called the names of his seven sisters just before he was shot down, nor from the hope that he would remain alive long enough to find them.