Jenine Abboushi

My uncle Walid, now 85 years old, looks like Eqbal Ahmad but moves like my father, I thought in Munich on my birthday this month, as I watched him dance gently to Oum Kalthoum, arms raised. Oliver Jamil, my cousin, likes his father to have the opportunity to hear Arabic, the music of his homeland, Palestine. My 17-year-old, Millal, and I were finally able to go visit him and our German family he had founded, all doctors. Like both my father and my dear friend Eqbal (Pakistani writer, activist, leader in the Algerian revolution during his Princeton years), both now gone, Walid is dark-skinned, gentle, with salt and pepper hair, and a twinkle in his eye despite his advancing senility. Oliver explained to him several times who we were (“who is this schön frau?”), and when he found out again, he chuckled, hugged and kissed us. Uncle Walid had the same chuckle as my grandfather in Jenin when I was a child.

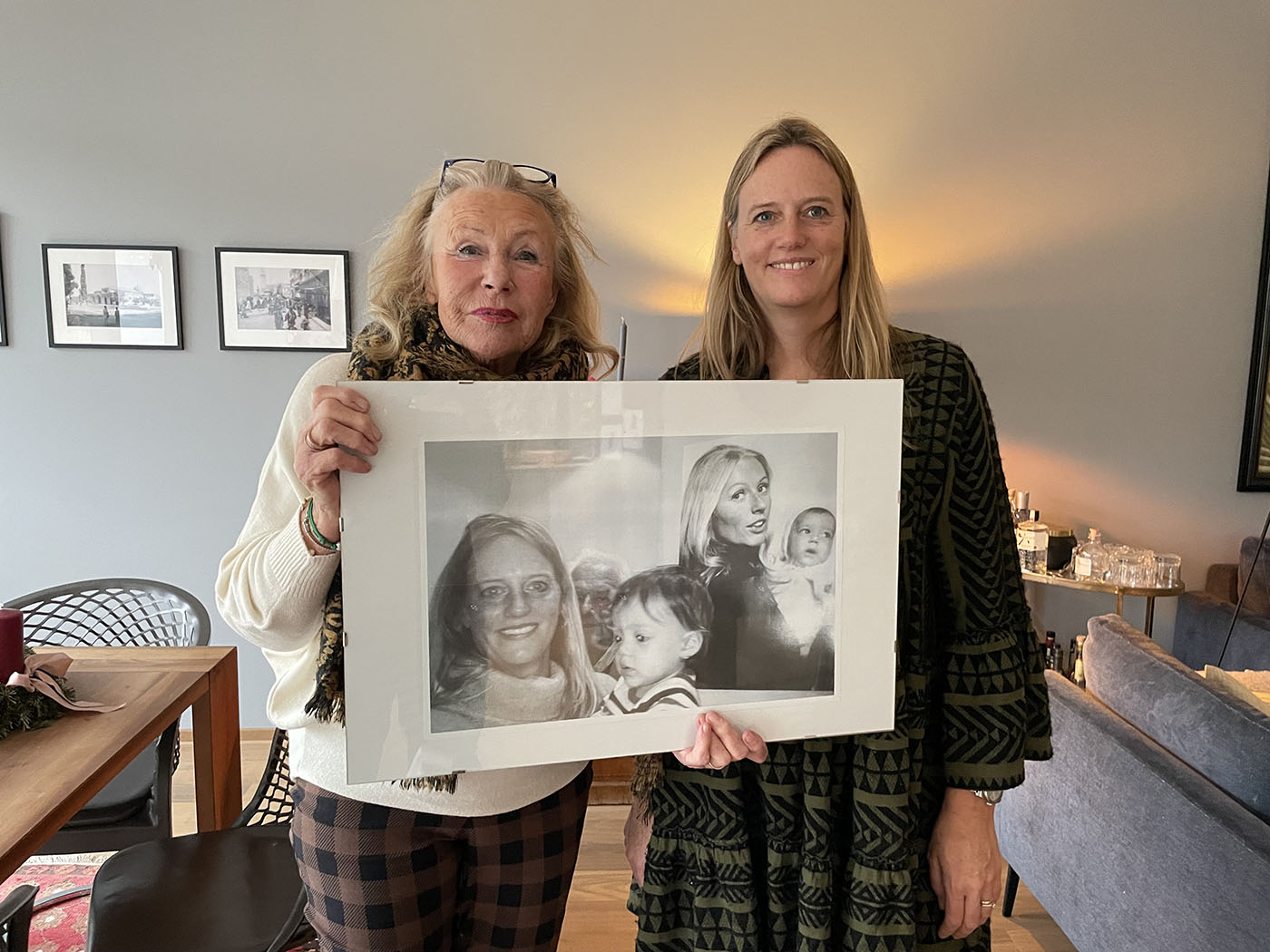

When Walid was young and married to Gudrun, the mother of his sons—fair and blond with much charisma and style—they made for a sexy couple. The year before the civil war when my family lived in Beirut, Gudrun once smacked Walid’s arm with her clutch bag, standing next to our table in a Hamra terrace-café, which only added to their cinematic magnetism. The grown-ups later speculated jokingly about what Walid may have done to upset her.

The two parted ways when their boys were young, and Gudrun now has Antonio, her droll and good-natured Italian husband. He naturally speaks to everyone in Italian, and if we answer in English he translates for us. By his presence, the family now speaks Italian without having lived in Italy or studied the language. Antonio quipped to Millal—during the Bavarian dinner that Oliver’s adorable wife Miriam and their two daughters prepared—that my uncle Walid will surely die “con un piatto in mano” (with a plate in his hand). This recomposed family gathers regularly for dinners and outings.

Gudrun is now a lively 80-year-old and is still a practicing doctor three times a week in Oliver’s private clinic. She otherwise spends hours a day with her younger son Alexander Tarek, who is now tetraplegic with severe brain damage and 24-hour care after an accident ten years ago. He had an allergic reaction to an antibiotic, fell unconscious to the floor in the Berlin hospital where he worked as a neurologist, with “not one, not two, not three, but four” doctors surrounding him, exclaims Gudrun, holding her fingers up. Oliver told me that those doctors, used to treating epilepsy, mistook Alexis’ struggle as an epileptic fit and tragically failed to resuscitate him in time. His mother tells us that he can still say “mama” and “Naela” (the name of Oliver’s 11-year old). She knows he can see some light out of the corner of his left eye, and can follow what we say. Oliver does everything for his brother, she explains, but he is more skeptical about Alex’s capacities. At one point during our visit to Alex that weekend, Millal and I realized we should not talk about whether Alex can follow what we say. Perhaps for his mother the idea that he cannot understand is unbearable, and for his brother the idea that he can understand, locked in immobility, is unbearable.

In my mind’s eye I can see Alex at the lake we went to outside of Munich with the family, when my daughter Shezza was five years old some years before his accident. He was gliding her along as she lay bare-skinned on a surfboard in the sunlight, the both of them chatting and laughing. We, their parents, looked on in delight of their mirth and beauty.

In turn, Millal and I talked to Alex during our visit, and he did seem to focus in on our words and presence. I told Millal to touch Alex’s shoulder while talking to him, because he cannot see. We all sat around a table in front of large windows overlooking a yard with leafy trees. Antonio and Gudrun showed us a video of Alex giving a lecture at the inaugural conference of an international association he had founded to explore the connections between neurology and aesthetics. The subject is surprising. We discussed how the psycho-emotional work of abstract contemporary art is intangible, powerful, probably hard to map in the brain, and perhaps neurology is a science of similar forms of power. I wondered briefly, looking over at him, how he feels when he hears his own voice from long ago. I saw that he had dozed off briefly. And I thought of his wife, as he was married at the time of his accident.

Gudrun handed me the description of the association, written in English, and I started to read it aloud. Alex listened intently and Gudrun tapped on our arms to say, “see?” And yes, as Millal later described, Alex closed his mouth and sat up to listen to what he had once written. We were at once moved and devastated. His mother told us that he has gotten better and he will still. “Ten years!” she exclaimed, gazing at me in her pain, and I leaned over to catch hold of her arm.

Soon Oliver arrived to fetch us to go to town with Miriam and the girls, Naela and Helena. We took leave of Alex. Oliver clasped his arm, and we told him we loved him. He straightened his body rigidly in his wheelchair, and squeezed tears out of his eyes. Stunned and heartbroken, Millal and I followed Oliver outside. We remain in awe of their devotion and love, all of them. It commands such respect, is rich with meaning, and conjures up our own love and sense of belonging. Our German family lives in a pretty area and within a five-minute drive of one another. The girls play hockey and music, sleep over at Gudrun and Antonio’s house regularly, and the adults have successful, satisfying careers. Each morning the girls rush to their Christmas calendar with the little hanging gifts. They open that day’s package, put together their new toys, and we eat breakfast while watching the two kittens attack the wrapping paper strewn on the floor. And they all lead contented lives that hold a tragedy, and discover ways to tend to all members of their beloved family.

Walking around in an open downtown market, Millal eating a delicious pickle wrapped in paper, the girls sipping fresh juice, we came upon the town synagogue, Ohel Jakob, built 68 years after the Nazi destruction of the original synagogue on Kristallnacht in 1938. “The stones are from Palestine,” remarked Oliver, “stolen.” Yes, the structure seems somehow familiar, I responded. But the stones were also defamiliarized here in Munich’s Jakobsplatz, far from home, and differently cut and mounted. Standing next to the imposing vertical rectangles of this mausoleum-like structure, we must have felt that we, too, partake in its reference to destruction and loss. We took a family photo in front of the millennial stones that here embody our hidden Palestinian history. They are the chalky, travertine stones that form the houses and buildings of our people, and now lend an authentic facade to Israeli settlements and monuments, quarried from Palestinian land and built by Palestinian labor.

That evening Oliver and Miriam invited us to dine in a chic Asian fusion restaurant surrounded by some of their friends and acquaintances. They took my uncle Walid along, as they often do, and he sat near Millal and I, eating contentedly, looking around at the giant, red-black photographs of boys’ faces lining the back wall, listening in half-comprehension to whomever leaned forward to talk with him.

A lawyer who accompanied Oliver to Jenin, and later helped with the German taxes following my uncle’s land sale, came to sit next to me and chat. He was friendly, and started up a political discussion. Had the Palestinians just taken what was offered, he argued, been less resistant, they would have lost less land. They miscalculated. “Would you not rather go back to 1975, when you had more land and there was no wall?”

I was not sure I felt like discussing with this lawyer. It is not that the Arabs and Palestinians did not make disastrous mistakes and follow wrong-headed policies along the way. But this is not what exiled us from Palestine. What has led to the disinheritance of our generations is Israel’s expansionist project, U.S. financial and military support (on a scale unmatched in history), and the impunity with which the Israelis continue to rob and destroy. I responded that even participating in our own dispossession has not stopped the Israelis. Look at the work of our fully collaborationist Palestinian authority, I said, and the Israelis accelerate, if anything, in land, property, and water theft. The lawyer informed me that I am making a moral argument, and yet I must know that strong, modern countries will choose to support Israel for strategic reasons.

Unfortunately, moral alliances do not have much power, insisted the lawyer again, and pragmatic politics has no use for defeated peoples the world over.

Millal tried several times to say something, but the lawyer ignored him. (“I’m not used to people not giving a shit about what I think,” he remarked later as we walked out.) The lawyer’s line oddly reminded me of a self-defense class we sat through in high school in the States. If we are sexually assaulted, the instructor explained, we should know that resisting could get us killed. Better to note your aggressor’s height and the color of his hair so as to be able identify him later. This shocked me at the time. I was recently relieved to read Virginie Despentes, who questions why we are not encouraged to kill our aggressors, even at risk. She wonders whether rape would be as widespread in this case.

Unfortunately, moral alliances do not have much power, insisted the lawyer again, and pragmatic politics has no use for defeated peoples the world over. This startling version of Realpolitik indeed jarred with our spellbinding family experience that weekend, to say the least. Millal and I held each other’s gaze as the lawyer made this final point about hopeless populations, and we stood up to leave. I slipped my hand through my uncle’s arm as we headed out. The lawyer walked in front of us with his gal, who suddenly held up a wooden skewer, pulled the last piece of chicken off with her teeth, laughing, and flung it to the ground in front of the line of waiters near the door. They were as stunned as I was, and I quickly bent down to pick it up, horrified that the waiters would be forced to do so. One took it from me as I stood back up, and we exchanged glances before I caught up with my family.

We left Munich, Millal and I, grateful to bear witness to and share in our family’s quiet, remarkable lives.