Sarah AlKahly-Mills

“Sharmouta.” Nadia expels the word from her chest like a breath held in too long, a late answer to a question that didn’t really need one. Anyway, she has only said what everyone else is thinking. “That’s the sort of woman who goes and does a thing like that, ya Giselle.”

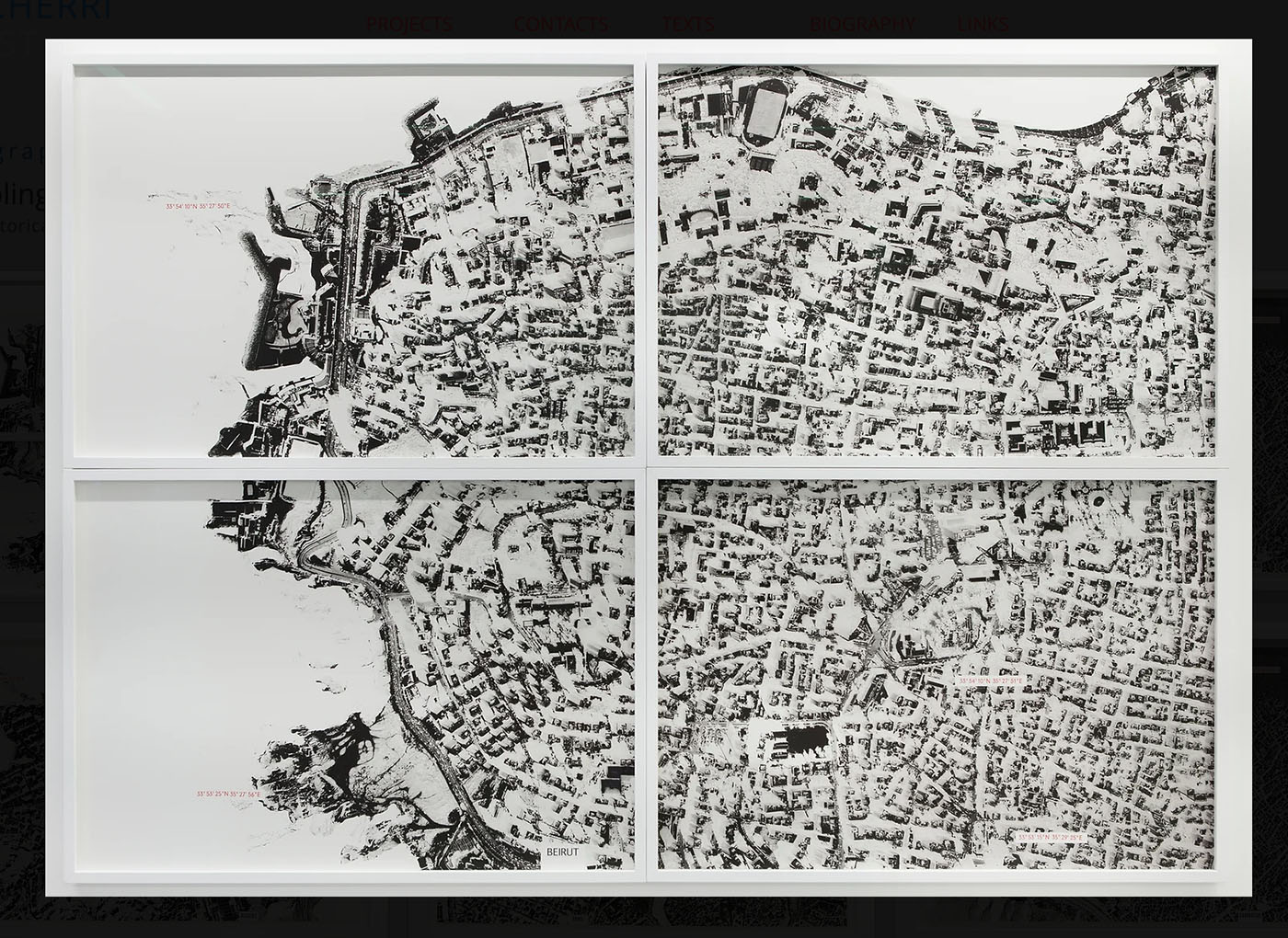

Thin Giselle sits in Nadia’s vinyl chair with her knees pressed tightly together and her elbows firmly by her sides. She raises her black, over-tweezed eyebrows in sympathy and passes a forefinger along the indigo enamel patterns of the coffee tray resting on her narrow lap. On the street below Nadia’s fifth-story balcony, men in yellow vests sweep up the shattered glass of the bank’s window where last night a woman fired shots, demanding her deposit.

“Your son, how is he handling all of this?” Giselle asks, blowing on the froth of her hot coffee before taking a loud sip.

Nadia’s gaze remains on the scene below. The sun bakes cracks into the asphalt. “You see that glass down there?” she asks. In the corner of her eye, she can tell that Giselle is watching her. This is how it has been for weeks now — her privacy a perforated, see-through thing with the eyeballs of everyone stuck into the spaces of its screen mesh, following her movements, blinking audibly. Even a trip to the neighborhood dekan has become a matter of running the gauntlet, dodging stares, some pitiful, others vindicated. All shiny with a thick glaze of judgment.

“They will never sweep it all away,” she says. “There will be pieces left behind. You’ll be walking there, thinking it’s clean, and a little shard will catch the sunlight and remind you of what happened. That is what that bitch Hélène did to my Joseph with her lies.”

The heat has become oppressive. They move back inside. The maid collects their cups, trays, rakwe.

Everything started out well enough; Nadia felt nostalgic for those early mornings when, seated alone at the kitchen table before her husband Marcel awoke, her ordinary morning reflections were pleasantly imbued with the novelty the girl brought them. Joseph met Hélène at university, where he was studying medicine and she music. He introduced her to them a few years ago, and she was, by all accounts, lovely: well-dressed, clean-smelling, from a good family, warm, polite. Muhtarama. Over dinner one night, dark eyes glittering with mischief, she made a strange crack Nadia thought was inappropriate, something about laundry and cooking and Arab men and Joseph needing to pull his weight when they got married, and it felt like a putting on of airs, like Hélène was trying to establish something too rigid, too soon. Couldn’t she be bothered with domestic tasks, or were her little music lessons taking up too much time? But then Nadia had wondered if it was not simply Hélène’s way of saying, “See, Tante, I’m not overstepping. I’m not taking your son away from you entirely. You can still spoil him in a way I won’t, if that is your choice.” Yet the idea of not wanting to dote on one’s own husband was, to Nadia, unfathomable — and dangerous. It left fissures in the foundation of marriage that someone could easily sneak into and widen.

There were many red flags, now that Nadia considered it all with the aid of hindsight, glaring warnings she could just kick herself for not heeding. The fact that Hélène enjoyed her own company far too much, for one. She even called it “me time,” like that, in English, like she was some woman in an American movie who was kicking her heels off after a busy day at a law firm, drawing herself a bath, and talking dirty on the phone to a lover. With a kind smile, as if in acknowledgment of her own childishness, she would say her goodbyes after lunch, protest offers to stay for a while, claiming she needed to retreat into her bubble, where she could “rest” her head and be frumpy in peace. Nadia had almost wanted to say something mean. What are you resting from? From being single? From playing your flute? From not dyeing your own damn grays?

But she’d held her tongue. Hélène was a good girl, after all. She just lived in her mind too much, carved out a special place for herself as though it were for someone she loved, the way Nadia might have set aside treats for grandchildren, had she had any. Alas, Joseph was an only child — a miracle one at that, and a boy to boot! One and done. No, pregnancy was not for Nadia. Neither was it for Hélène, apparently.

Then there were the “debates.” That’s what Nadia and Marcel called them when they chewed over their evenings with Hélène after she’d gone. Her parents must have never taught her the art of polite conversation. Nothing was off the table for that girl. She made Nadia squirm in her seat and glance up at the maid every five minutes during that unnecessary homily on the rights of foreign workers. It made Nadia sweat at her temples as though the parish priest had written a sermon especially for her, though she’d done nothing wrong, no, she would even go so far as to say she had done everything too right with the young Sri Lankan woman, so much so that she began to fear her kindness was being taken advantage of — too many day-off requests to tend to a sick child no one ever saw, a silver tea set poorly polished. And when foreign workers were not the cumbersome centerpiece at the table of dinnertime conversations, the Palestinian cause took their place, and Nadia, like a child made to feel guilty or else protest a false accusation, declared how she had donated money to funds for Palestine when she was young, before the civil war broke out. Other times yet, something unfortunate would befall a woman and it would be in the news and then it was the plight of women that kept Hélène’s tongue occupied, and Nadia couldn’t help but sigh or roll her eyes. The child had no idea how good she had it.

“Do you know about the women who came before you, my dear, how bad it was for them?” she retorted one day.

“Of course, Tante Nadia,” Hélène said, holding her gaze in a way that Nadia might have mistaken for affectionate. “That’s why weeds need to be pulled up by the root.”

In that one October, before the pandemic, before the blast, before everyone became either too tired or too angry, Hélène took to the streets with protesters’ slogans scrawled all along the bare flesh of her chest and arms, a loudspeaker in her hand. On Facebook, she put up videos of herself denouncing ministers, and spent much of her time rallying her friends and organizing distributions of food and aid to needy families. Nadia couldn’t put her finger on what Hélène seemed to be doing wrong. Perhaps it was the loudness of it all, the intense emotion behind everything the girl did that felt like too much, like ostentatiousness, like a vulgar shriek by someone wanting to be seen and heard. Truth be told, though, the video that made the rounds online and in WhatsApp chats of some woman kicking a minister’s gun-toting bodyguard square in the groin tickled Nadia no end! Khai! She felt something flare in her chest to see it, and then she wondered if she was a bad person for being so amused. What was it about Hélène, then, that failed to inspire the same admiration, or at least amusement, in her regard?

It must have been intuition. She must have known that Hélène, sooner or later, would disappoint, though Nadia would never have imagined she would accuse her own husband of being a monster.

How could someone with as clean and righteous a public image as Hélène’s be so corrupt? Nadia thought of Joseph, how needlessly he must have been suffering, how gracefully he carried on in his work, quiet and poised as ever.

“How did it come to this?” Nadia asked her son one evening, shortly after Hélène did the irreparable damage.

“I don’t know, Mama,” he said, still in his lab coat, his face haggard.

“She’s always liked performances, that one,” Nadia said through her teeth. She fetched a rag and went to town on the porcelain curios atop the credenza, the slivers of space between books lining the shelves, seeking out specks of dust the maid had overlooked in her perennial rush to get out of their house.

“She has no proof,” Joseph said after a long silence during which he stared at his shoes and Marcel paced the floor of their apartment with his hands behind his back.

“A violence like that carries signs, always,” Marcel said.

Nadia had wanted to say something then, but in the moment that opened between thought and vocalization, a frightful thing happened in her stomach that felt very much like falling down a shaft.

She put a hand over her belly to quiet the terror, gripping her dust rag with the other.

“You would kick so much, Joseph,” she whispered, the gesture reminding her of the fact. She almost felt a ripple, the echoes of a child who couldn’t wait to leave the womb, and everyone gathering around the undeniable blessing it was.

Only suffering is lonely, she thought as she dyed her hair copper in front of the bathroom mirror, even when it is a spectacle.

Ya 3ayb el shoum 3alaya, Nadia’s cousin Hoda texts in their family WhatsApp chat. Hélène seems to have dug her heels in only further, the latest update from her reaching Nadia via a screenshot from Hoda.

I am not interested in preserving a pretense of family peace. If you are trying to convince me to lie to myself and to others, then spare yourself the trouble of texting me, Hélène wrote. The juxtaposition of her words and her smiling profile picture was jarring.

It was validating at first for Nadia to see everyone rush to her side, to defend Joseph and denounce Hélène. If everyone saw things a certain way, then they must have been so. But a suspicion began to tug at the corners of her mind. Whenever the group chat would become inactive, someone would find an excuse to revive it, as though it were a divertissement for them. To acknowledge it soured Nadia’s tongue with disillusionment.

“Can you believe these prices?” says a man to her left at the supermarket. She looks to him. He holds up a jar of peaches in syrup. He has a full head of gray hair now but also the same hazel eyes, as warm as ever, and a smile that has never failed to make the heat rise to her face.

“Khaled?”

“I thought it was you, Nadia. How long has it been? You look the same, you know.”

“That’s not true at all.”

He returns the peaches to their shelf. “How are you doing, Nadia?”

“As well as anyone can be doing here. How are you?”

“Meshe el hal.”

“The last I heard you were in Dubai.”

“I still work there. I’m visiting now.”

“Why?”

Khaled laughs, and Nadia prays that she is not too pink under her eyes.

“This place is a liquor that calls you back to the bottle even after you’ve promised yourself you’d never give in again,” he says.

“Let’s switch places, then. I’ll go work abroad and you can stay here getting drunk.”

He laughs again, and she never would have thought they could fall so swiftly back into easy camaraderie. But then again, when was the last time she even allowed herself to think back on Khaled without shooing the thought away like a pigeon on her balcony or a temptation come to alight on her shoulder and whisper bad things in her ear?

“You still make me laugh like a schoolboy, Nadia.”

They linger at the market for a while and reminisce. Wartime never seemed so pleasant as when recounted by Khaled, its brutalities mercifully omitted and only its shared university courses, escapades to the cinemas, and stolen — forbidden — kisses exalted. Of course, he doesn’t say that last part out loud, but Nadia fills it in, like a mind making up for the obscured details in a dark room, working solely off good memory. They exchange phone numbers and promise to stay in touch, and Nadia wonders about the wisdom of this. Before leaving the market, she sighs to see Marcel’s sister wave her over.

Later, she learns what else Khaled has omitted — a terminally ill mother he has come to retrieve and whisk away to Dubai — and he sends her a message: I heard you’ve been having family troubles. I am very sorry for this, dear friend.

How quickly even the most unremarkable news travels, like a bad smell in a closed room. Nadia can hear the sharp, tinny blink of eyes all around her. She relives the pain of leaving Khaled all those years ago, of settling into a practical and sanctioned marriage as though it were a career choice, accounting instead of theatre, of the nausea and despair coiled at the mouth of her stomach, waiting to spring into words full of venom.

They never did. She resents her silence, resents Khaled for reminding her how much music she once had inside of her.

“He’s a friend from my university days, Marcel,” she tells her husband. “Nothing more. I wonder what your sister was trying to achieve, though, making it seem like I’m some flirtatious floozy.”

“Don’t flip the script, Nadia,” he slaps back, as efficient as a fly swatter. “This isn’t about my sister. She only said she saw you with a man she didn’t know.”

“Does she know all the men in the world?”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Dakheel Allah, ya Marcel, what is there to say? That I ran into an old friend? Do I need to report back to headquarters, to account for everything I do or say?”

This outburst earns her a silence prolonged over days, which Marcel interrupts only that evening to say, as he eats the mloukhieh she’s made: “That whore’s red hair color is positively garish on you. Have I ever told you that? Why don’t you do something sensible, like that Giselle?”

She has never done anything like this before in her life, so she wants to try, just once, to be perfectly cruel and vindictive. She’s taken the sharpened paring knife from her kitchen and gone to wait outside the apartment Hélène is staying in now that she’s moved away from Joseph. She knows well the girl’s schedule — Hélène will be leaving for university lessons soon — and has timed the proceedings in a such a way as to have the satisfaction of seeing her reaction. It is early morning and still dark out. Hélène’s old white Kia is parked along the curb. Nadia begins with the front tire on the driver’s side, working quickly, turning her face away from the hiss of air.

When Hélène emerges from her apartment and reaches her car, she doesn’t notice right away. She sits inside and starts the vehicle up. Nadia watches her from across the street, flattened against the wall of one of its buildings, holding her stomach in as best she can. Hélène turns off her car, steps out, and examines the damage.

Let’s see the show she puts on for us now, Nadia thinks, expecting the girl to smash the windows in and wake up the whole neighborhood with her fury, but Hélène only slumps down the side of her dusty and dented car and, hugging her knees to her chest, cries quietly as the sun breaks over Beirut. Nadia recognizes it. The Last Straw Cry. It is lonely and resigned.

Nadia clutches her purse closer to her body, feeling the outline of the knife’s wooden handle through the soft leather. She moves away from the wall.

“Come,” she says, and it sounds more like a clearing of her throat than words, “come,” and she is walking toward Hélène without understanding why.

Hélène lifts her head. Her face is streaked red. Her dark eyes, always so large, are pinched small.

“My car is parked just down the road. Come. I’ll give you a ride.”

“Why?” Hélène whispers.

“How are you going to get to your lessons?”

“Why is your car parked down the road?”

“That’s none of your business. Now if you want a ride, come with—”

“I don’t need your help.”

“Don’t be stupid.”

“Was it you?”

“What are you talking about?”

“Did you do this?”

“Did I slash your tires? Do I have nothing better in life to do? Don’t be absurd.”

“You have no reason to want to help me, Nadia, and I understand that. I accept that.”

“For God’s sake, Hélène.”

Nadia begins the short walk to her car and, to her surprise, Hélène retrieves her bags from the back seat of her Kia and follows. The ride is quiet. Nadia can smell the discreet scent of Hélène’s lavender perfume, and it reminds her of the day they made atayef together, when she and Joseph were just beginning to court.

“What have you gained?” Nadia asks. “I want to know what you have gained by doing what you have done.”

“Slashed tires, Tante, and handwritten threats delivered to my door.”

“My whole life, I did everything right. And this is my reward. What proof do you have anyway? A violence like that always carries signs. Like Mona. Ya haram. Covered in bruises. No one doubted her. Do you see what I mean, Hélène? It isn’t personal. It’s just that — why should anyone believe you? It’s he said, she said.”

“And when Mona came to you all, what did anyone tell her but to be patient and that her husband loved her and that he was stressed?”

“She hasn’t complained about him for years.”

“Why would she turn to the same people who told her to stick it out, to see how much pain she could take?”

“Joseph would never do what you said he did!” Nadia slaps the steering wheel with both hands. “Never!”

“I thought so too.”

“I raised him!”

“It isn’t your fault.”

“I gave my life to him.” She can feel her throat close in on her voice. “I gave him everything. I did everything right.” She pulls the car to the side of the road before they reach the university. “This is as far as I can take you, Hélène. Please get out.”

Hélène gathers her things. After stepping out, but before turning to leave, she bends down to window level and says: “My mother always says the same thing, that she did everything right. But for someone who does everything right, she is so deeply unhappy because she doesn’t understand that there are people you’ll never satisfy, no matter how good a beating you can take and stay quiet. I’m sorry this happened, Tante Nadia. I loved the way you would sing while you cooked.”

At home that night, as Nadia cores zucchini, she hums through her tears. Marcel watches the news, so she cannot sing at full volume, as much as she would like to test her voice. She would sing for Joseph, when she was pregnant with him, just to feel him move, to know she hadn’t lost him like the ones that came before.

She leans over the counter, the pile of vegetables to her left, the paring knife in the grip of her right hand. She throws it into the sink and pulls at the strings of her apron, tearing it off herself and knocking an empty glass pitcher to the floor, where it shatters. She sinks to her knees.

“What is going on in here?” Marcel asks, having rushed in. Squatting, he takes her hands in his. “Are you all right?”

“Do you remember when we were younger, much younger, just before he was born, and you wanted to and I didn’t, I was too far along, I was worried for the baby—”

“What are you talking about? Come, stand up, or I’ll be picking glass out of your knees for days to come.”

He holds her up by her forearms, but she shakes herself free.

“Do you remember that night?”

He shakes his head and sighs. “No, Nadia. What’s making you think about one night decades ago?” He retrieves a broom and dustpan wedged between the fridge and the counter and begins to sweep up the glass.

Nadia covers her face with her hands and weeps. Marcel leans the broom against one of the kitchen chairs to hold her and rub her back, and she rests her chin on his shoulder. Beyond him, in the window of the living room, she can see a dozen pairs of eyes watching her. She collects herself, wipes her face with a corner of her apron, picks up the paring knife, and resumes hollowing out the zucchini.

“How many times I could have blabbed about things but didn’t, just to keep the peace!” she says. “How hard is it just to shut up? How hard can it be? People talk, but they’re not there to pick up the pieces. They’re not there. Where is she now?”