Is This How You Eat A Watermelon? by Zein El-Amine

Radix Media 2022

ISBN: 9781737718420

Rana Asfour

With the short stories in Is This How You Eat A Watermelon? a Lebanese American author treads in the well-traveled world of such predecessors as Antonin Artaud, Samuel Beckett, Eugene Ionesco, Jean-Paul Sartre and of course Albert Camus, who in The Myth of Sisyphus (1942) elaborated his theory of the absurd, which as one observer put it, derives from the “futility of a search for meaning in an incomprehensible universe.” Here tension arises between our desire for order, meaning, and happiness and the indifferent universe’s refusal to provide that. And yet, fiction, no matter how absurd or surreal, can in some way be viewed as ultimately a response to reality. In Zein El-Amine’s slim debut collection of stories, where war and trauma are the perpetual landscape, the line between reality and fiction is blurrier than ever, ensuring a reading devoid of the comfort blanket of pure make-believe. Immediately as the book begins, we are treated to El-Amine’s brand of absurdity:

In July of 2006, Israel invaded South Lebanon in a military operation called “Summer Rain.” The IDF always wanted to demonstrate their literary prowess to western powers by putting literary labels on their invasions — a previous operation was actually called “Grapes of Wrath.” The poetics here lie in the fact that Lebanon does not have any rainfall in the summer. In fact, all the rain is confined to the winter months. So “Summer Rain” is code for planned carpet bombing.

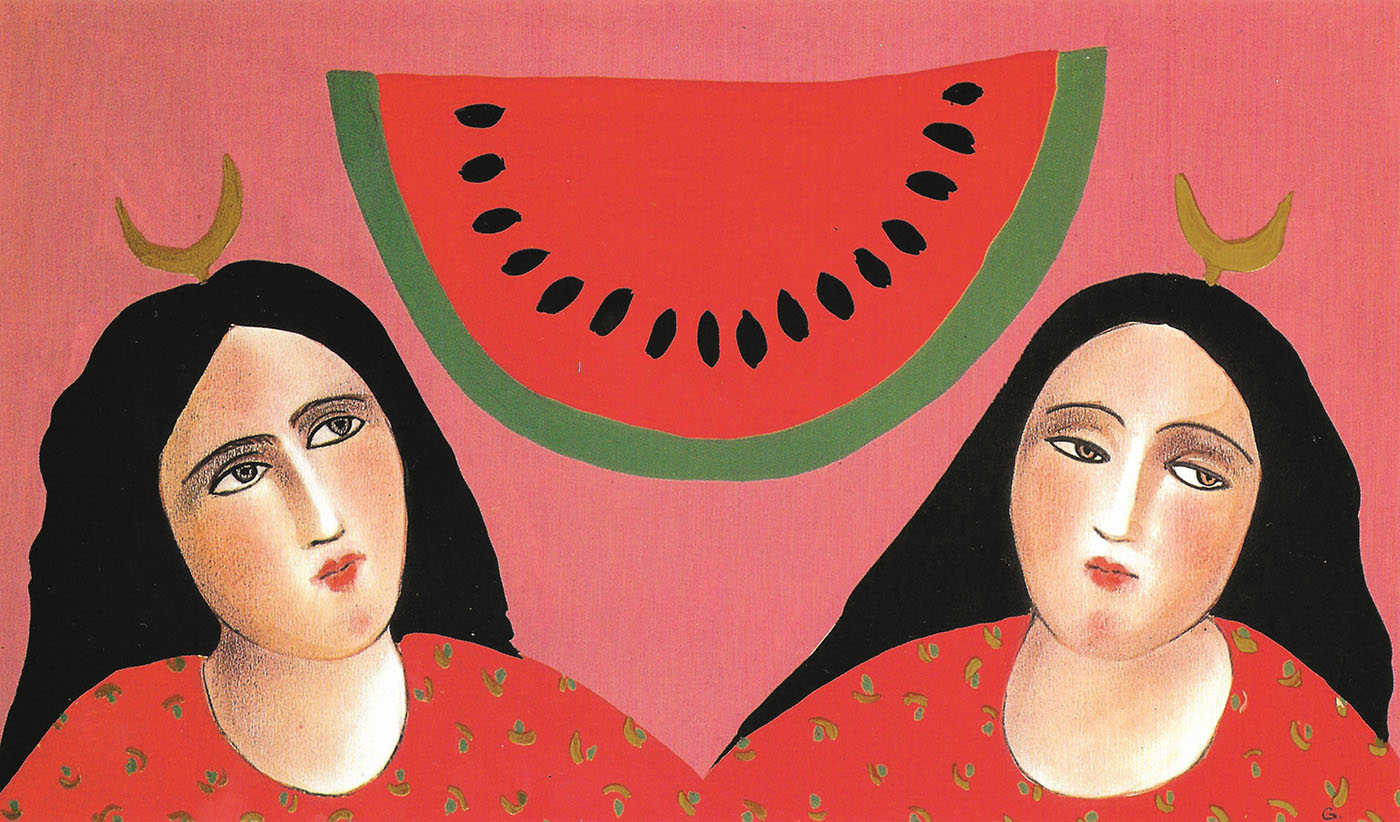

Winner of the 2021 Megaphone Prize (formerly the Own Voices Prize) and published by Radix Media, Is This How You Eat a Watermelon? comprises seven stories that are set around the 1980s in South Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the US. Each story is resplendent with plenty of authentic touches regarding terrain and personalities to render it believable while pushing the boundaries far enough to enthral the imagination. In the titular story “Is This How You Eat A Watermelon?” Ghassan, whose carpe diem attitude infuriated his family and charmed his two wives, finally lands him in hospital with kidney failure among other health crises. Irredeemably mischievous whether in the house rolling about with his children, or roaming about in the wilderness among the scorpions, beehives and snakes, Ghassan’s antics get him into all sorts of trouble. In one instance he is terrified when one of his shenanigans proves near catastrophic to his beloved daughter.

It was a June afternoon of bearable dry heat … Ghassan looked up and saw Huda nibbling along the top of this red semi-circle of a slice that dwarfed her face.

“Is this how you eat watermelon?” he asked. She looked at him puzzled and waited for clarification.

“Is this how you eat watermelon?” he repeated. She started to worry, as he was not using his usual terms of endearment.

Then he added, “Do you eat it like this?” and imitated her nibbling. Huda looked back at her mother for help and caught her stifling a laugh.

“Do you eat a big slice of watermelon like a bird, like this, nm nm nm?” he pecked at his slice with his nose, pinkies raised.

Huda broke out in a smile that prompted Ghassan to explain. “You eat it like this, like a goat,” and Ghassan went into typewriter mode, chomping wildly at the slice from one end to another, watermelon seeds flying left and right. So daddy’s girl took the tip and ran with it, imitating him, putting her whole face into her slice of watermelon, filling her mouth and nostrils with it, digging in deeper until the rind curved up around her face. She looked up at her father with a long red smile that extended up to her ears, watermelon seeds entangled in her curls. He rewarded her with a pat on the back and kiss on the top of her head.

When Huda later suffers from laborious breathing and is taken to the doctor, it is to Ghassan’s horror that he is told of a watermelon seed lodged in her nose. The seed had sprouted and was slowly suffocating her. Ghassan remains resolutely convinced of his invincibility and smug with his fatalism, until the only recourse is to face up to the truth of his mortality and the wreckage left in the aftermath of his shenanigans.

Verisimilitude ultimately discomfits the reader as one reflects on Lebanon’s volatile bloody past and its turbulent present. Suddenly, the barrier between fiction and reality comes tumbling down, and like the children in the story “Birds of Achrafieh,” one alternates between “the nausea of trauma and the sweet sense of solidarity” for a country that is today in total financial collapse and a southern front still caught in an ongoing war with Israel, whereby 2022 marked the first time the IDF used its warplanes on Lebanon since 2006.

The opening story, “Sharife and the Party of God,” is an anecdote about his peculiar aunt Sharife, who lives in Deir Keifa, in the south of Lebanon. Sharife, a “tiny tendon-wired woman with salt coursing through her veins,” is a chain smoker. It is 2006 and Israel is carrying on with its farcically-named “Summer Rain” operation, intended to carpet bomb the south for 72 hours to rout the popular resistance that had “expelled them from the country at the turn of the millennium.” Sharife’s family members have all fled to Beirut following several failed attempts to persuade her to go with them. Left alone to fend for herself, she soon runs out of cigarettes and launches a tirade of curses against her fate, the Devil, the Chinese, and later herself when she finds that she has run out of things to curse. When the Israeli bombardment is at its zenith and a Lebanese squadron passes her house on their way to seek shelter out of the city, she enlists their help to buy cigarettes. For safety reasons, they refuse and she is furious.

“The Party of God you say? More like the Party of Satan! Go ahead, march.” She rings the flashlight like a marshaller guiding the plane into its dock. “March on to red hades if I care! If it wasn’t for this catastrophe that you got us into I wouldn’t be without cigarettes … God curse you all,” she whispers. “There is no more humanity left in this world.”

In “Send My Regards to your Mother,” a youthful, carefree Shiite Lebanese American narrator (whom the author chooses to name after himself) is locked up in a Bahraini prison when he is caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. The youth had been visiting from Dhahran where his father worked as a contractor on a US military base. The story oscillates between the absurdity of his naiveté and the uncouthness of his captors, to the eventual trauma that the incident leaves within him. The horror of his predicament hits home and he finally stops taking mental notes for storytelling sessions with his friends when he’s asked to hold up a placard with a name, number and “suspected terrorist” written on it:

“Empty your pockets.”

I hesitated. Having watched way too many American law and order type shows, my first response was to request a phone call. I actually said, “I am entitled to a phone call.”

Smiley beamed at me. “Oh yes, you will get your call. You can call whoever you like.”

My joints were turning to jello from elbows to knees. I did not have much on me—a few Bahraini dinars for lunch, my trusted military base ID, which I felt was my only ticket out of here, and compacted remains of a Kleenex. He checked the pockets of the shorts and pushed them back toward me. “You can keep this,” he said and handed back the shorts.

In the story the youth is kept in filthy conditions for six days with inmates who have been incarcerated without charge for no less than six months. There, he receives a coming-of-age education, where “seeing a chained man pray allowed no room for cynicism”; where brutalized men talked about their families “in the past tense, never the present, and certainly not in the future”; and where resilience was order of the day. When his luck finally shows up and he is released back to his family, he hears one visiting woman tell another that the experience nearly killed his mother. “Yes,” his father confirms, “they almost did kill your mother.” And yet, years from the incident, we find that the narrator has no recollection of his mother on that day and has in fact chosen to remedy his trauma with apathy and erasure, rather than deal with the pain and anger that continue to fester within him.

“Maybe she is missing because she fell ill months later and died within a year of that day, from lung cancer, at the age of 53. Maybe that day was what connected her death with my imprisonment. Maybe I want to sever that connection. Maybe I do not want that child with his OP shorts, ignorant of the consequences of his actions and sleepwalking through his youth, to take any responsibility for the disintegration that ended the life of the person he loved the most and who loved him the most. Maybe the anger that simmers under my surface today, that constant roil, started on the day where I connected the deeds of that murderous government with my personal tragedy. They whittled away at her until she was gone. Maybe that day is the day I lost any measure of healthy fear.”

Despite the tragic aspect of the story I found it to be the funniest and most enjoyable of the collection. That is, until I later learned that it was based on the author’s real prison experience such that it did not seem so funny anymore. In one interview the author tells Zeyn Joukhadar that many of the details mentioned in the story are true: “From the OP tennis shorts that the youth is carrying when he is stopped to the tee-shirt that he is wearing, that’s all real. I was just like in the story, wearing a tee-shirt that had two cats sitting on a trash can, stoned and it said ‘That’s right! We baaad.’ You can’t make up this shit!” he jokes.

In fact, readers would not be wrong to consider Is This How You Eat A Watermelon? a sort of fictionalized autobiography. Besides the incarceration, other similarities crop up between the author and the stories that he tells. For one, all the main characters hail from the Lebanese south, just like the author. In “Birds of Achrafieh,” the little boy who gets picked on and shamed for his accent in the boarding school is unnervingly something that happened to the author at his own school, and “killdeer” is a literal mirroring of El-Amine’s trajectory from engineer to creative writer who consciously chooses political undertones in his writing in homage to his Arab heritage and the legacy of ghosts they unwillingly inherit. Even the titular story was conceived after the author attended an acquaintance’s funeral, and in “The Groom” the author writes of Saudi Arabia where he also lived and from which issues of hierarchy and class are material sources that crop up in a number of the stories.

In all, the seven stories are portraits of proficient and empathetic storytelling about war, about desperation, and about the restlessness of the peaceful world that some of the characters inhabit. That said, El-Amine’s fiction demonstrates how violence destabilizes cultures and individuals, shattering realities long after the violent act itself has passed and irrespective of where the traumatized and dispersed end up as unprocessed trauma nestles in the subconscious mind and memory.

Each layered and intricate story stands alone, peppered with throwaway details that illuminate its characters’ lives. The result is a revelation of compassionate disclosures: of an old woman alone and lonely left to fend for herself; of tortured men incarcerated indefinitely without charge or trial sharing their meagre food rations with the cell’s new resident; of how a dying man in the collection’s titular story who “loves his food, his drink and his family, or families” becomes an allegory of a city crumbling under the weight of its residents’ insatiable consumptions; of traumatized children who age in one hour; of how a man who sees life as a series of absurd loops eventually ends up living in the same city that makes the bombs that once blanketed his village; of a Lebanese poet who struggles to convince an angry audience that wants war and not his poems of love (for the natural beauty of New Zealand) that it isn’t “poetry’s responsibility to shed light on events the world chooses to ignore.”

Deceptive in their simplicity, the stories are by turns funny, heartbreaking, gripping, and thought-provoking, with wit and grace a key feature in the gloomier ones. None bar one offers a satisfying conclusion, and even then it is anything but the one that the narrator had been expecting. Is This How You Eat A Watermelon? is a work of fiction that excels in its intimate exploration of the human condition in which the absurd is the new normal, in which ‘they’ become ‘us’ and literature and knowledge are rendered a binding experience.