Reflections—Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa, edited by Venetia Porter, with Natasha Morris & Charles Tripp

British Museum Press, 1st Ed

ISBN 978-0714111957

Malu Halasa

In 2000, ten years after the end of the Civil War, Lebanese artists bristled at foreign critics and curators who tried exoticizing them under the banner of “Arab” or “Islamic” art. At the time regional curators were starting to emerge in Beirut, Cairo and Jerusalem, but few Western museums were collecting contemporary Middle Eastern art, and it would be many years before multinational museums emerged in the Gulf. If modern artworks were acquired, as they were in the 1980s by the British Museum, they were overshadowed by the museum’s more extensively displayed collections of Islamic art and objects. This changed with the 2011 Arab Spring or Awakening, with art in the frontline, using satire and stark imagery against corruption, misrule and state brutality.

Reflections—Contemporary Art of the Middle East and North Africa, edited by the museum’s Middle East curator Venetia Porter, with Natasha Morris and Charles Tripp, introduces a selection of the 170 Arab, Iranian and Turkish artists and artworks in the British Museum’s contemporary Middle East collection. Richly illustrated, the book elucidates the journey the art and artists have made from their respective art scenes and countries to international collections. Some of the artists remained at home in their respective countries; others are working in exile, or in the diaspora. Recognition has been a long time in coming. In the spring, the contemporary collection will be exhibited for the first time in the British Museum.

One of the collection’s prescient works, Dark Water, Burning World, 2017, by Issam Kourbaj (b. Suweida, Syria, 1963) was recently installed as Object 101 in the BBC Radio 4 series, History of the World in 100 Objects. Kourbaj, who lives in Cambridge, fashioned a flotilla of little boats from bicycle mudguards. Each one carries a cargo of burnt matchsticks. The work was created during the height of the arguably not totally over migrant refugee crisis.

Porter, who has been with the British Museum since 1989, explained to the BBC, “It’s so important for us as a museum … to collect works like this because they are documenting moments in time. It’s as though art is also a document. But by saying ‘document’ it renders [art] sterile. It doesn’t.”

She concluded, “It’s that [art] has that ability to speak to us in so many different ways.”

Art Versus Religion

Reflections opens with art that challenges long held assumptions about Middle Eastern visual culture. An Islamic proscription against representation gave rise to the belief that human form in art from Muslim countries was somehow forbidden, despite traditions of Persian miniature painting and Byzantine influences from the earliest days of Islamic art and architecture, which suggested otherwise.

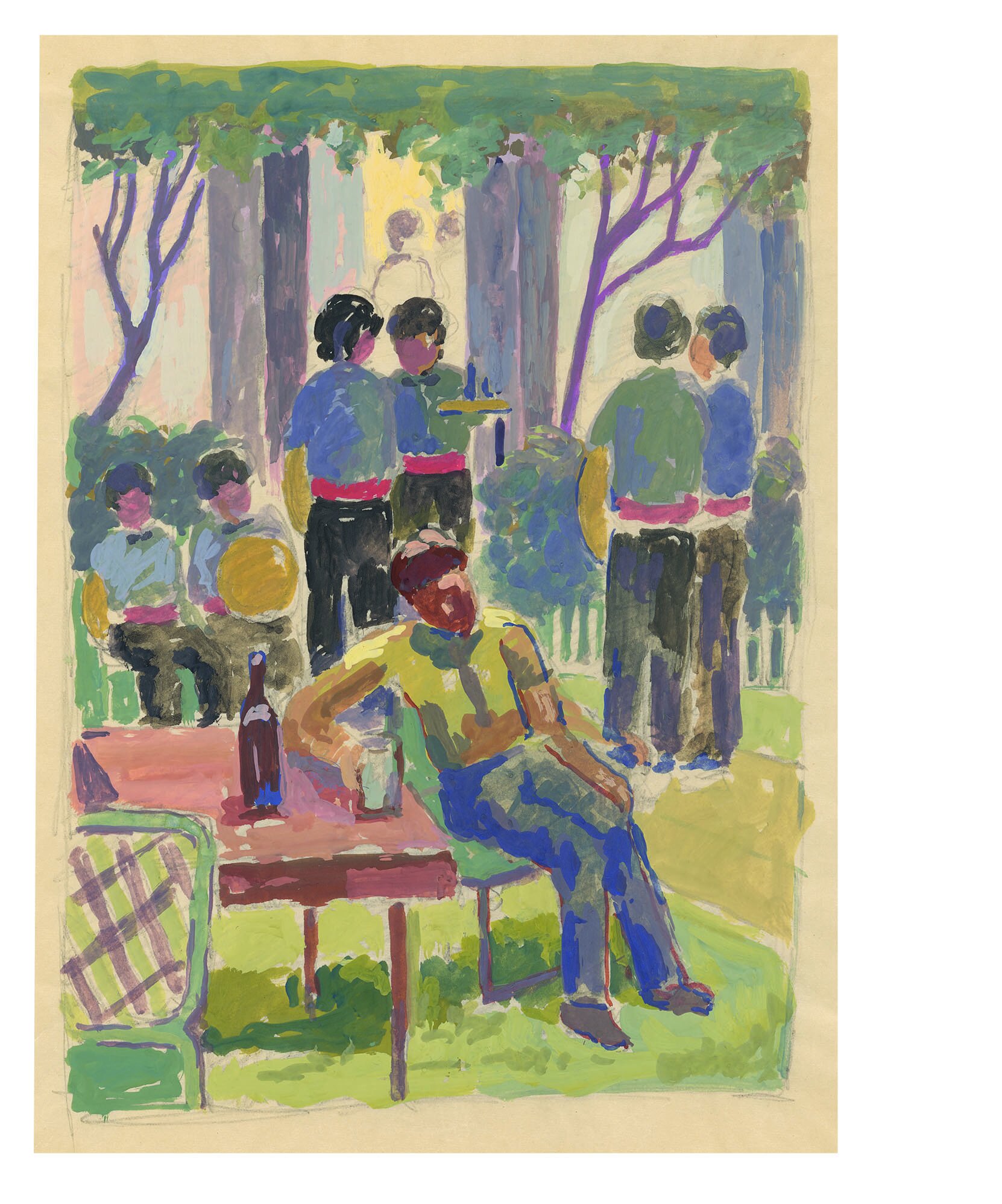

To his parent’s dismay, Iraqi modernist Hafidh al-Droubi (b. Baghdad, 1914–1991) would draw people as a child. In the collection, his work captures the pomp and circumstance of a Ba’ath Party procession—as well as solicitude in the watercolor Drunken Friend in the Alwiya Club Garden, 1976.

Safeya Binzagr (b. Jeddah, 1940) from Saudi Arabia studied printmaking in 1970s London and filled a notebook with pencil sketches of faces for an etching she was making at Central St. Martins. Her tutors wondered whether this art practice could continue after she returned to her religiously conservative home. Now Darat Safeya Binzagr, her private gallery in Jeddah, exhibits portraiture and offers drawing classes.

Both artists had been influenced by modern approaches in art from the West. In the introductory essay for Reflections, Porter cites oil and canvas, sculpture and printed image, among other mediums, as constituting “a clear rupture with [the region’s] traditional or historical Islamic art … ” that had been rooted in calligraphy, geometric abstraction and less figurative or representational work.

Iranian art historian Fereshteh Daftari had been an early proponent of rethinking the use of the word “Islamic” to describe Middle Eastern artists or their art. The term “the Arab world” was also problematic, and not just for the artists in Reflections from Iran and Turkey. How could a blanket expression encompass the wide-ranging experiences of artists who happened to live in or came from the 22 member states of the Arab League?

An important debate was taking place within the British Museum, as Porter writes, “whether the modern and contemporary art should be considered another phase in the story of Islamic art … ” or whether ” … the fact that artists may choose to express themselves through forms and techniques associated with historical ‘Islamic art’ does not necessarily make their art ‘Islamic.'”

The turning point for the institution came in 2006 with an exhibition she curated. Word into Art: Artists of the Modern Middle East showed that the artists had deep aesthetic and cultural ties to calligraphy. However, as Porter points out, “the forms of the script could be taken beyond their literal meaning, and in many of the works, the writings themselves could be read as commentaries on the histories and politics of today.”

Finally there was recognition that these artists, unhinged from the mantel of religion, constituted a powerful modern movement in their own right. This would be a critical development in the creation of a viable contemporary collection for an institution long considered a museum of history, one with a significant legacy of colonialism.

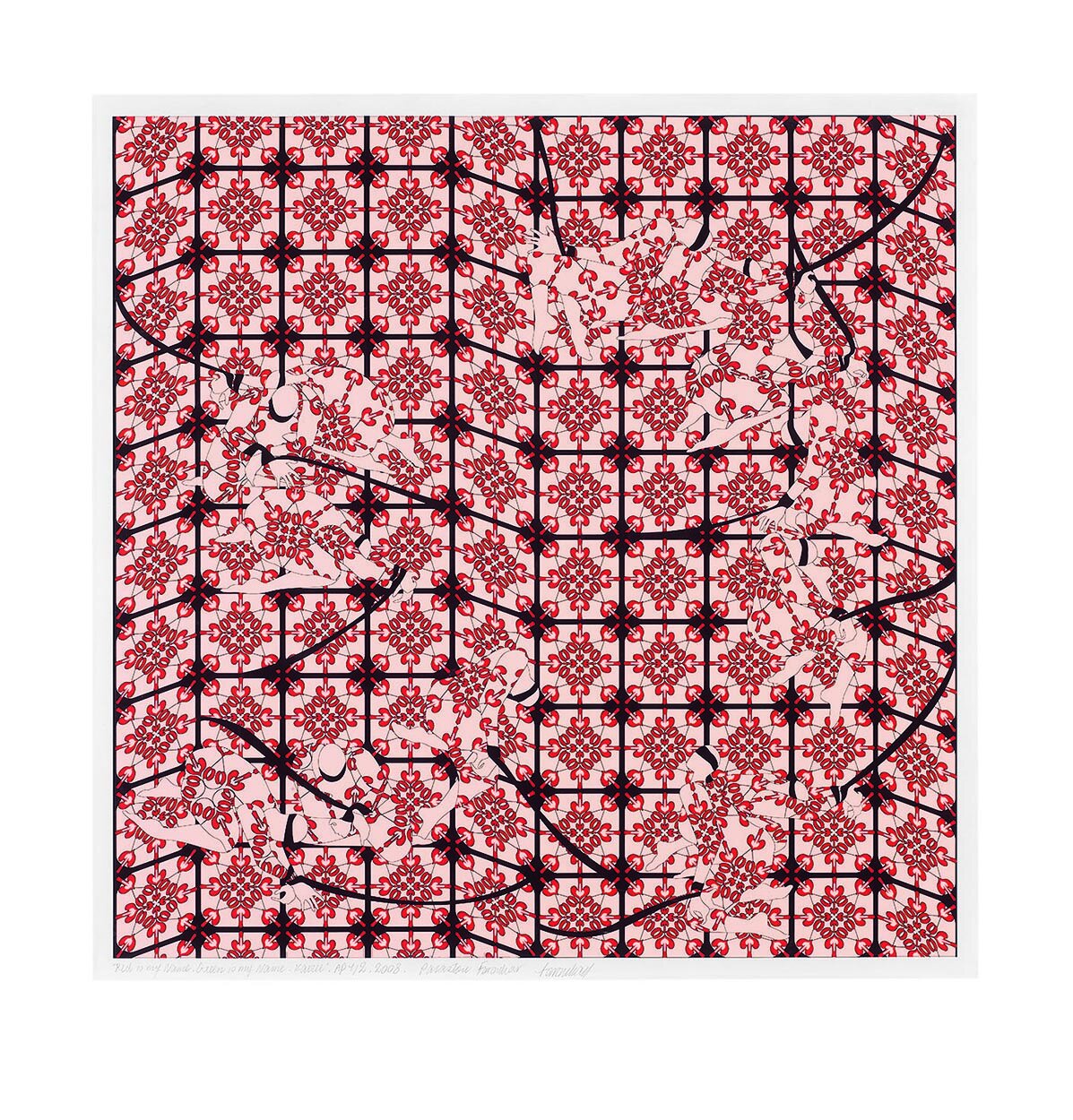

In Reflections, Parastou Forouhar (b. Tehran, 1962) plays with the deliberate ambiguity of imagery for the four digital prints, Red Is My Name, Green Is My Name—Karree, 2007. The abstracted colors of the Iranian flag and a geometric grid don’t disguise the body parts. The artist’s parents Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar were assassinated during the 1998 campaign of violence against intellectuals in Tehran. This was another example of “art as document” that Porter referred to on the BBC.

Every Home Should Have One

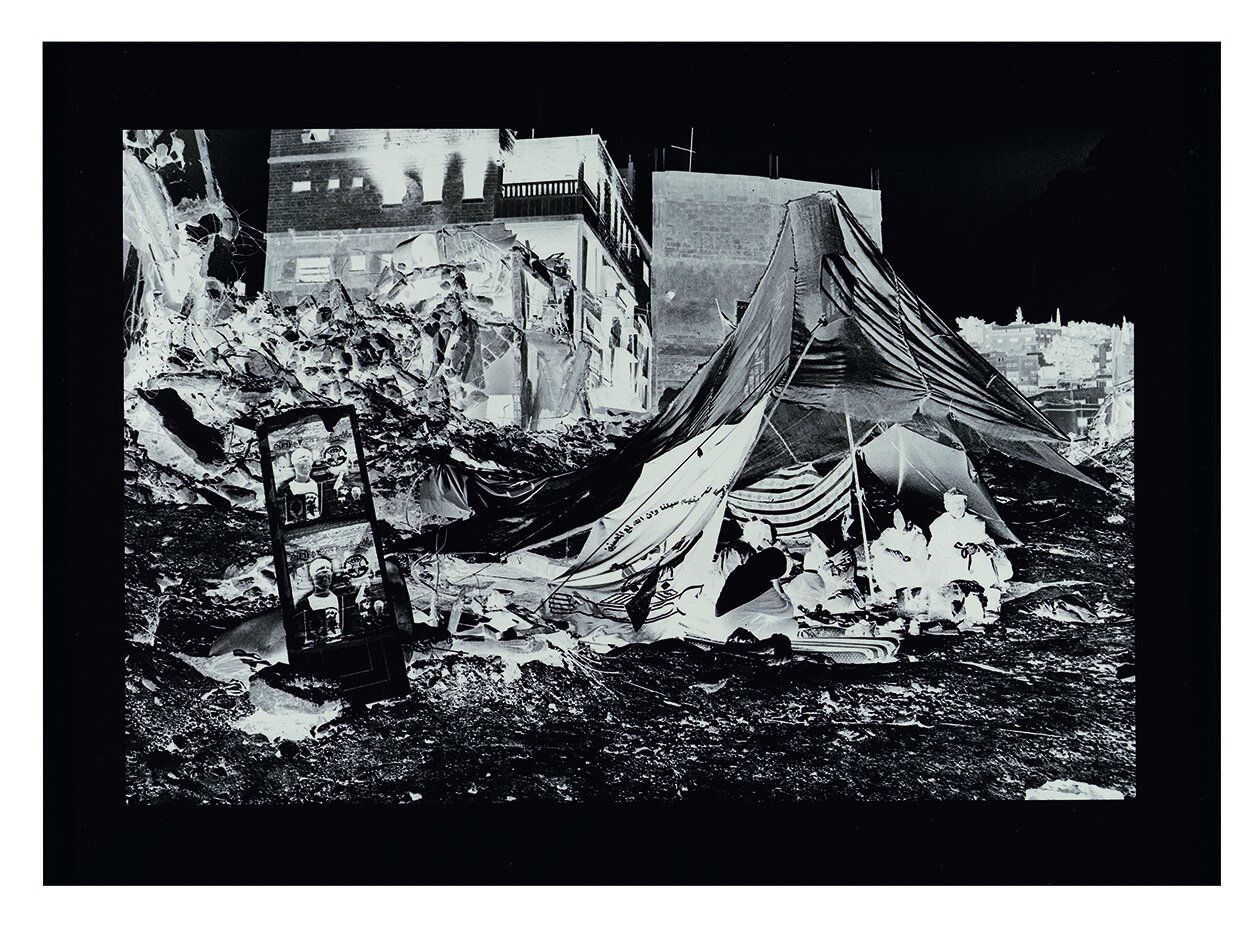

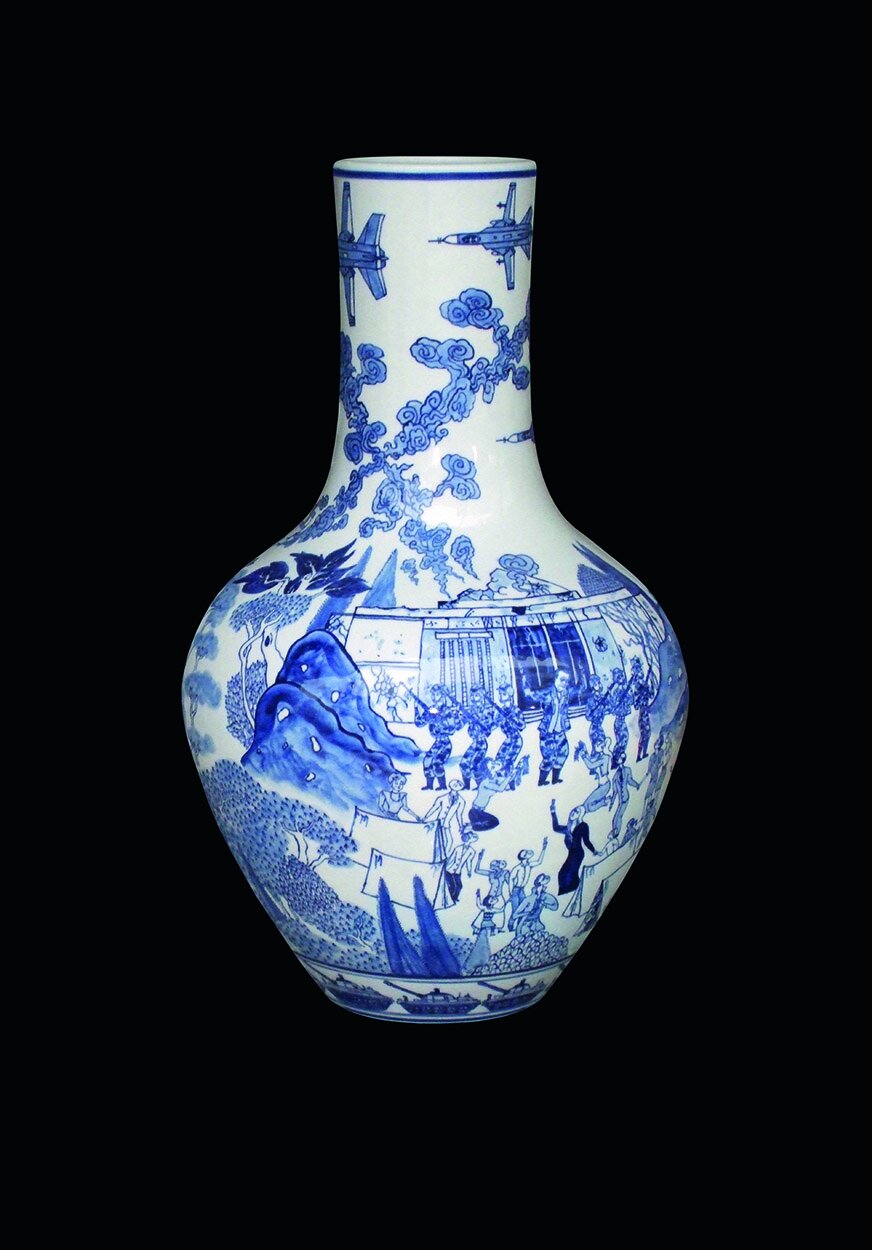

Works on paper make up most of the art in Reflections. Among the exceptions, which include artists’ books and Kourbaj’s boats, is the darkly humorous, hand painted glazed porcelain Chinese vase. It is one of three collected by the museum from the series Yassin Dynasty, 2013, by the conceptual artist Raed Yassin (b. Beirut, 1979).

The timelessness of the vase’s traditional blue and white Willow Pattern jars with the almost televisual imagery of modern war. Syrian MIGs encircle the neck of the globular vase. On its body, armed Syrian soldiers face off against Lebanon’s General Aoun. Refugees emerge out of their UNWRA tents to scour the skies.

Reflections also includes the original drawing made for vase by Lebanese illustrator Omar Khouri (b. 1978), which was copied by porcelain craftsmen in Jingdezhen.

Yassin told curator Nat Mueller for Ibraaz that, “By putting … a very sensitive issue like the Lebanese Civil War … on decorative items, I get rid of it, in a way—it becomes like a vase, for the house. I want to have this vase in every house, so everybody could just get rid of it. I just want to get rid of the issue, make it more like a decorative, throw-away item.”

Yassin’s vases and Forouhar’s digital prints were acquired for the museum by CaMMEA (Contemporary and Modern Middle Eastern Art), an acquisitions group formed by art patrons from Iran, Egypt, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the U.A.E. CaMMEA has worked closely with Porter since 2009 and has provided most of the financial support for the contemporary collection. It also covered artists’ fees and the costs of printing for digital artwork by new generation Syrian artists, from the book Syria Speaks, which I coedited, and which traced the creative outpouring of the Syrian Revolution.

The posters by the anonymous Syrian collective Alshaab alsori aref tarekh (The Syrian People Know Their Way) and the illustrations of Sulafa Hijazi (b. Damascus, 1977) are art of revolution and popular political movements. The posters, produced during the 2011–12 mass demonstrations against Bashar al-Assad, were disseminated online, then downloaded, printed out and carried on marches by demonstrators—art as social commentary in a very charged contemporary setting.

In Damascus, Hijazi too was in the streets. People she knew had been arrested. Worried for her own safety, at night after she worked on her illustrations; she hid them deep in her computer where no one could find them. Her images shock in a different way. Instead of memorializing scenes of a war long passed in the art, violence has permeated the fabric of everyday life. At the wedding in one of Hijazi’s prints, a bride and groom wear gasmasks.

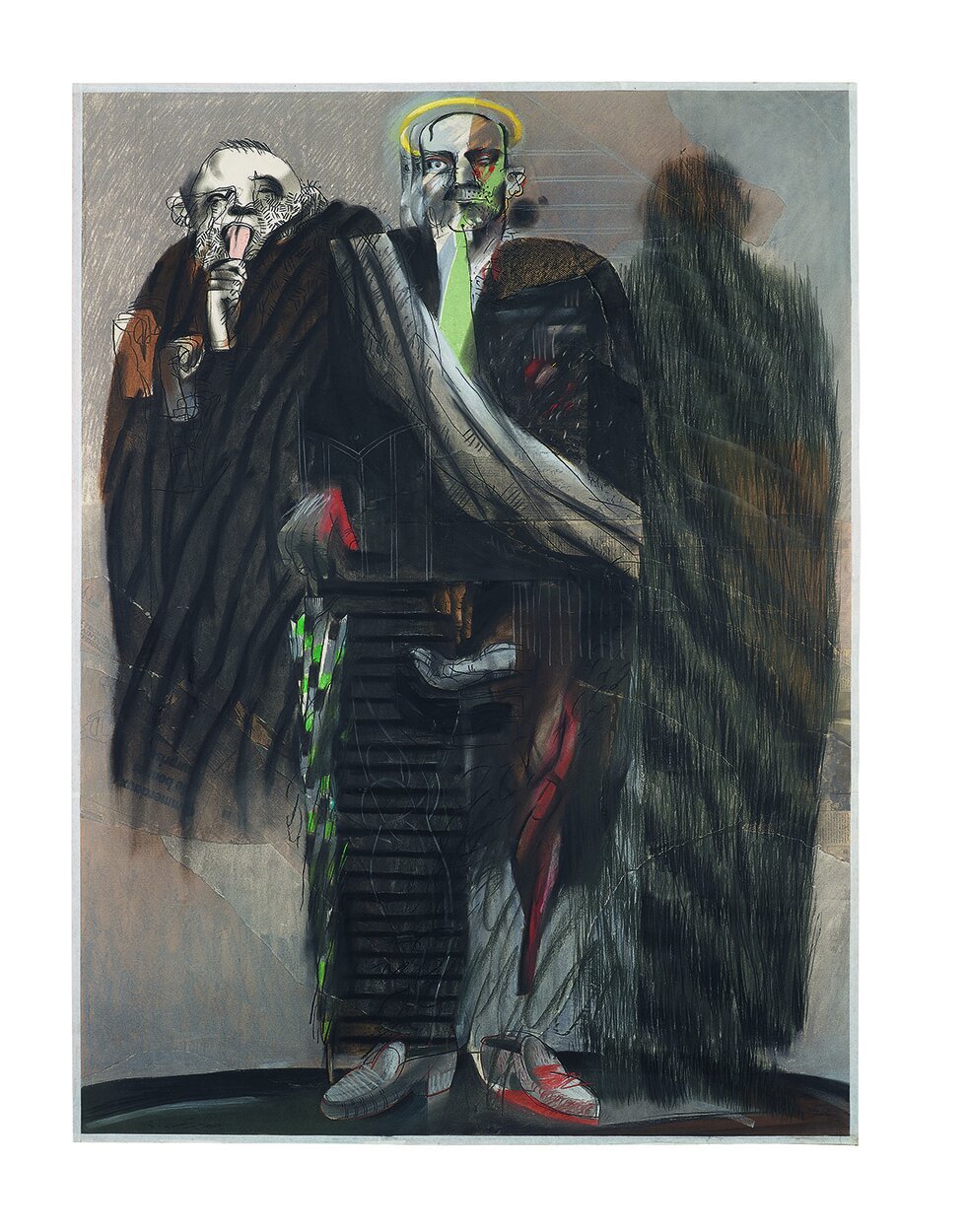

In the book’s chapter on Political Struggle, Revolution and War, the artists have been grouped by geography. This allows a younger artist like Hijazi to converse through imagery and content with a more experienced Syrian artist. Youssef Abdelke (b. Qamishli, 1951) is no stranger to totalitarianism. Imprisoned in the 1970s, he was released and he lived many years in exile. His much-heralded return to Syria in 2005 was considered as a thaw in the Assad dictatorship. In 2013, he was disappeared again, this time for five weeks, after which he was suddenly, inexplicably released. His pastel and collage Figures (No. 2), 1991–93 of monstrous men lurking in the shadows is chilling.

Gender, Another Battlefield

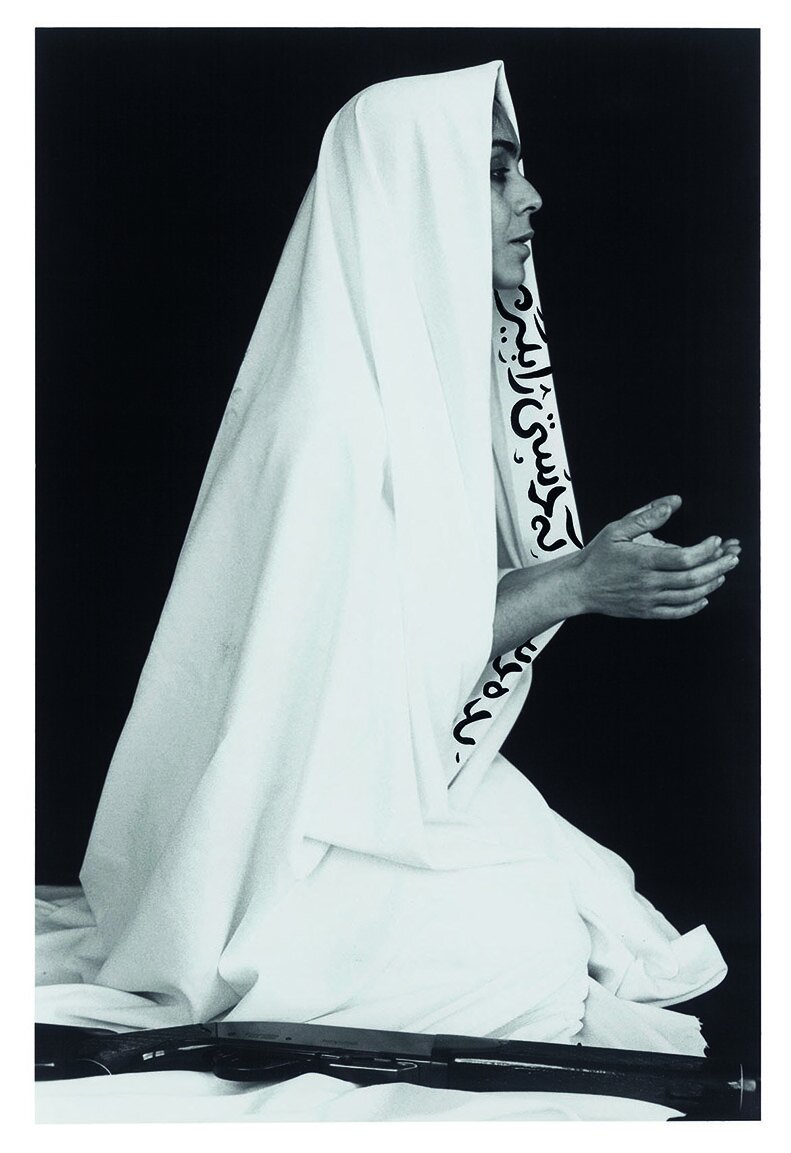

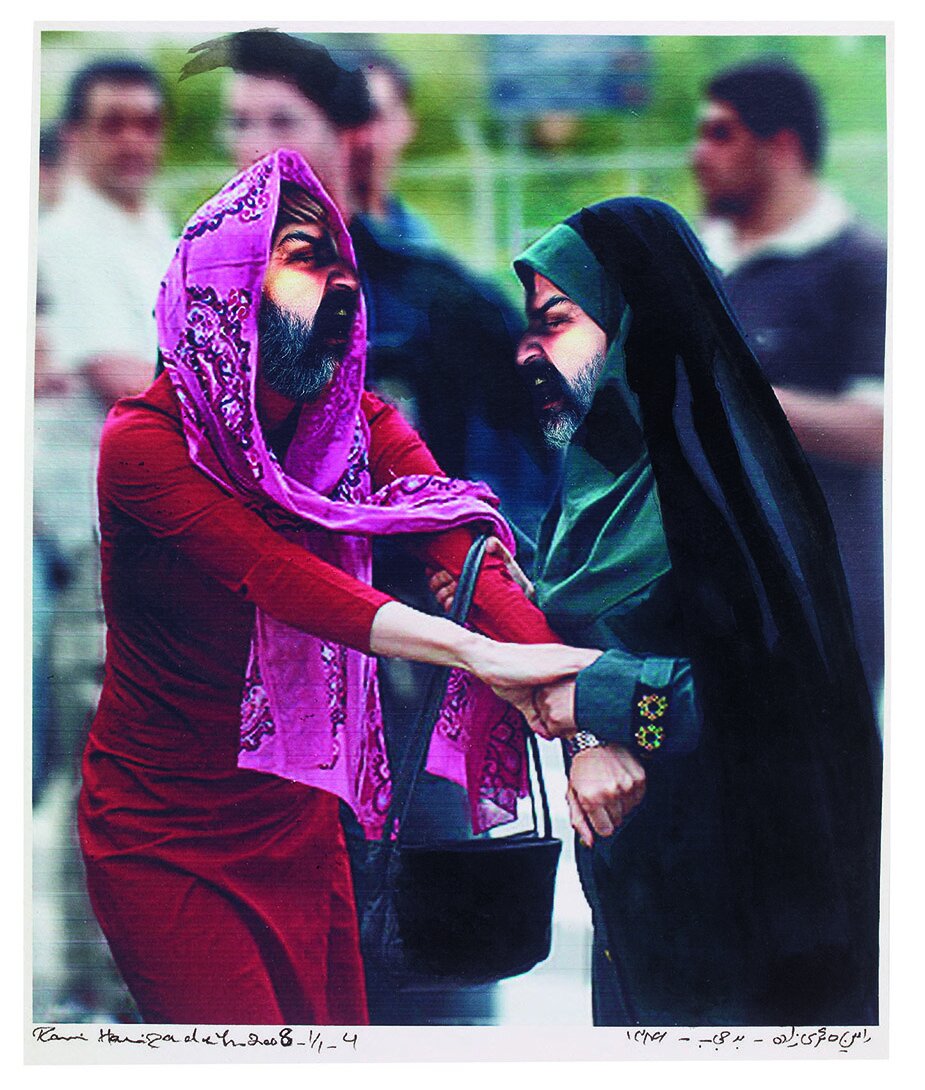

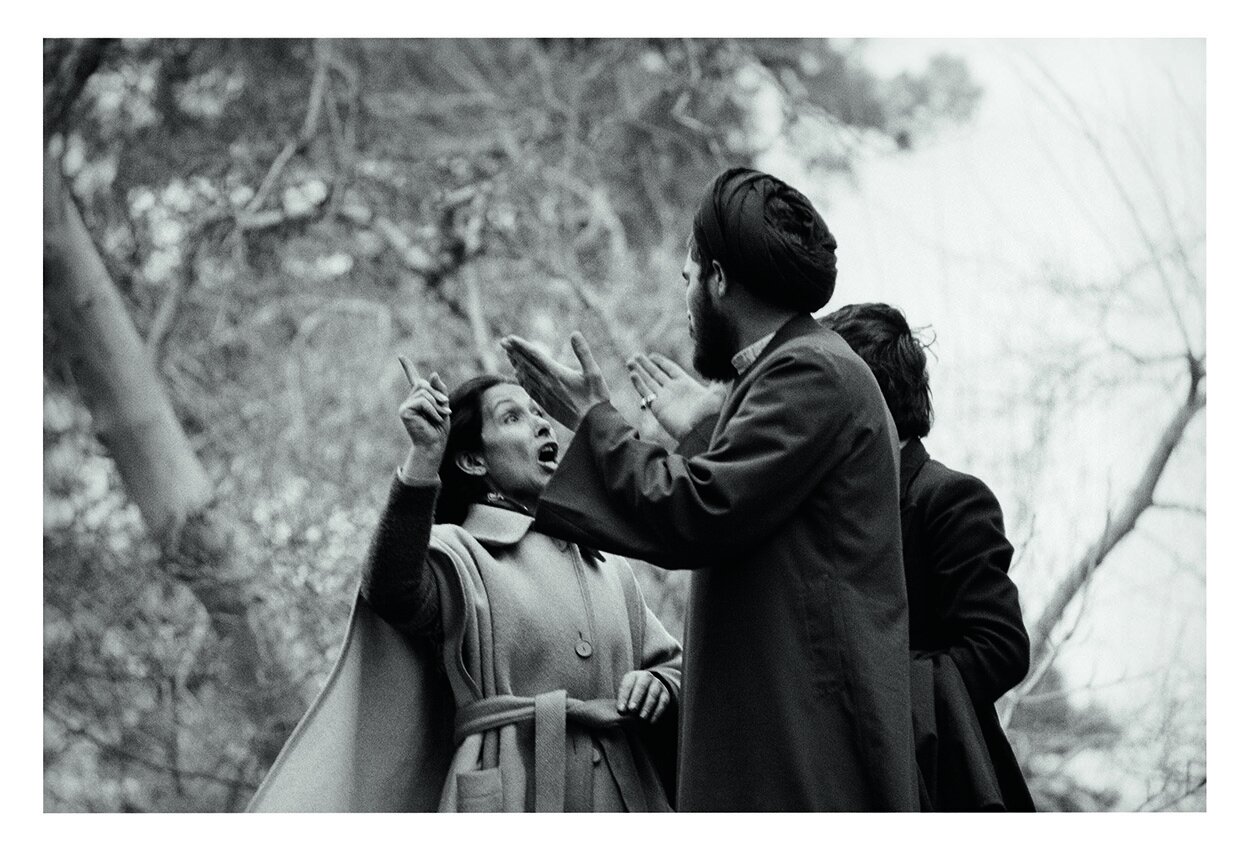

Iranian photography in the chapter on the Female Gaze meets on the indices of history, faith and pop art. A 1979 black-and-white photograph of a protesting woman hectoring a mullah on the last day before the enforced wearing of the hijab, by Hengameh Golestan (b. Tehran, 1952) and an artist’s self-portrait in contemplation and prayer from the series Women of Allah, 1995, by Shirin Neshat (b. Qazvin, Iran, 1957), provide counter blasts to the photo collage Bad Hejab, 2008, by Ramin Haerizadeh (b. Tehran, 1975).

Haerizadeh took Internet images of women rebuked or arrested for not covering their hair and superimposed his bearded face over theirs. It is an image that could be construed as representing the nameless men who harass women every day on Iranian streets. The effect is both comical and enraging.

“For female artists,” writes Charles Tripp in his essay Art and Power, “questions of gender, tradition and faith informed many of their works as they sought individually to understand the place of Islam in their lives and the forces that used religion or the appeal to tradition to circumscribe their lives as artists and as women.”

He continues, “Inevitably, this brought them up against forms of power and censorship, driving some into exile, a fate they shared with male artists when they too drew attention to the ways in which state authorities used Islamic justifications to keep women (and men) in their place.”

Tripp, an academic, is known for his books on Middle East politics and government. Despite being married to Porter, he came late to art, after the Arab Spring.

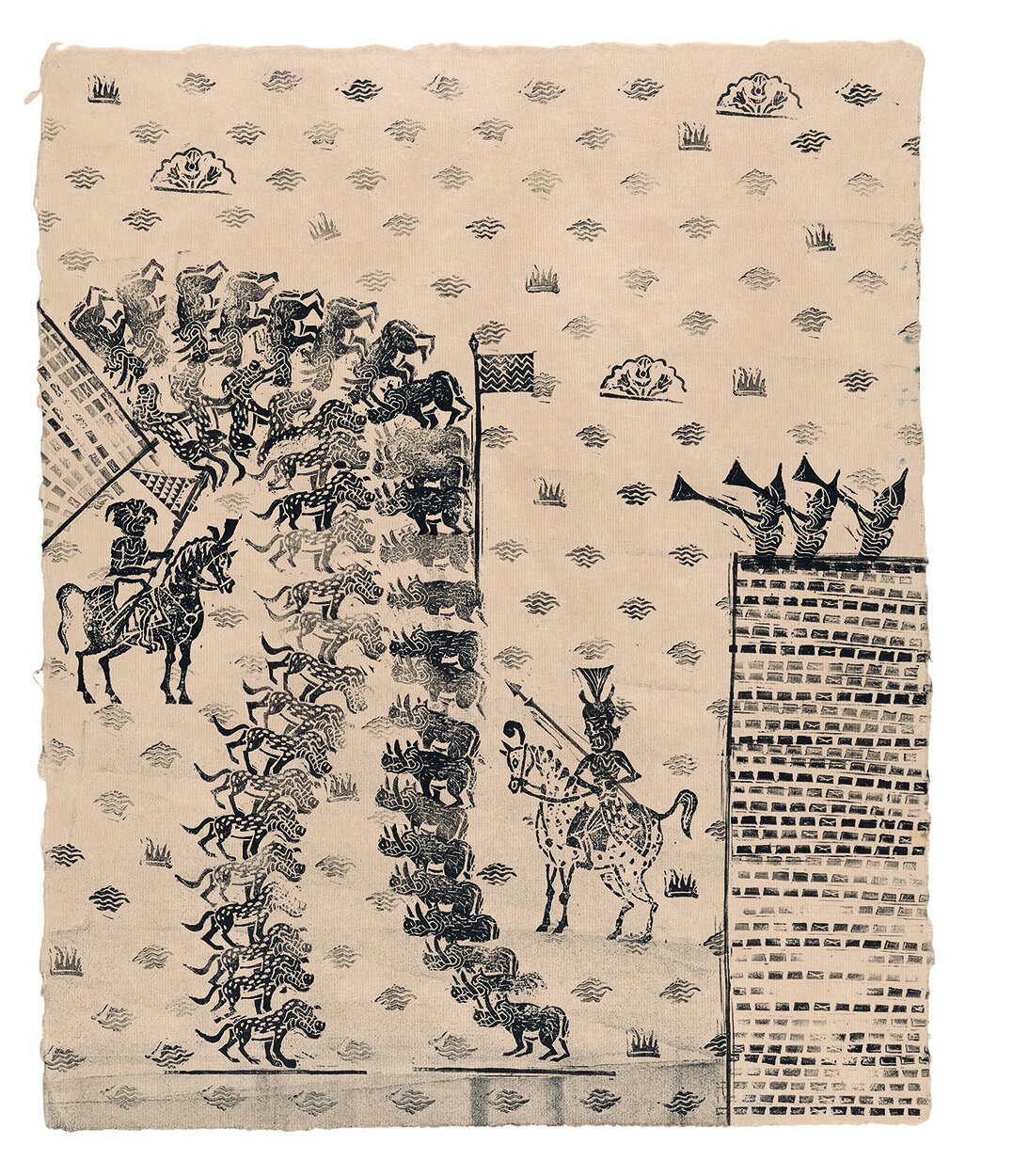

Some of the artists in Reflections provide a more theoretical critique on the optics of moral combat. Iman Raad (b. Mashhad, Iran, 1979) was inspired by the folk art of Persian coffee shops; the animal fables of Kalila wa Dimna (translated from Sanskrit into Pahlavi and then into Arabic, in the eighth century); and George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Hand-carved stamps were used to create two opposing armies of divs, or mythological creatures, on a seemingly one-dimensional field of battle influenced by from the monochromatic flatness of nineteenth-century Qajar-era lithography. It is another telling subversion of an older art form.

In combat, the artist told Porter, ” … there is no clear binary of good and evil.” An over-emphasis on the winners and losers of Middle East conflicts effectively obscured the people on the ground. This was the main reason that foreign governments, Middle East watchers and academics completely failed to predict the Arab Spring. Since then, not only has there been more of an appreciation of MENA art in the West, more attention is now being paid to art, artists, even street artists, in the region. Twenty years ago, when those Lebanese artists were complaining, there were only a few homegrown initiatives supporting them. Now NGOs like AFAC (Arab Fund for Arab Culture) and the Beirut Art Center have changed the cultural scene.

History & Art

A timeline in Reflections juxtaposes political history with specific arts milestones. Bookended by hope—Iran’s 1905 Constitutional Revolution and the 2019–20 forced resignation of Algeria’s president Abdelaziz Bouteflika—it shows that in between wars, genocide, forced migrations and military coups, contemporary art seeded itself in the MENA region.

The first art schools opened in Jerusalem, Cairo and Tehran under colonialism, in the early 1900s. By 1931, Cairo had the region’s first contemporary art museum. Fine art academies followed in Lebanon and Iraq at the end of that decade. In 1951 the Baghdad Modern Art Group was launched. For the newly independent countries, art was perhaps not a priority; but still, by 1959 a faculty of fine arts was established in Damascus.

By then Iran had already pulled ahead in terms of contemporary art production. The first art biennial took place in Tehran, five years after a U.S. and U.K.-backed coup removed Mohammad Mosaddegh from power. Sixteen years later, in 1974, the Arab Biennial was held in Baghdad. Nearly two more decades passed before the Sharjah Biennial took place in 1993.

After the national museum and library of Iraq were looted during the U.S.-led military overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003, London slowly emerged as another center for Middle East art. Since then politics has outpaced art. However, a global art movement aided by the Internet and fueled by a proliferation of regional biennials and international museums and art auctions and sales allow some artists to live and work wherever they are.

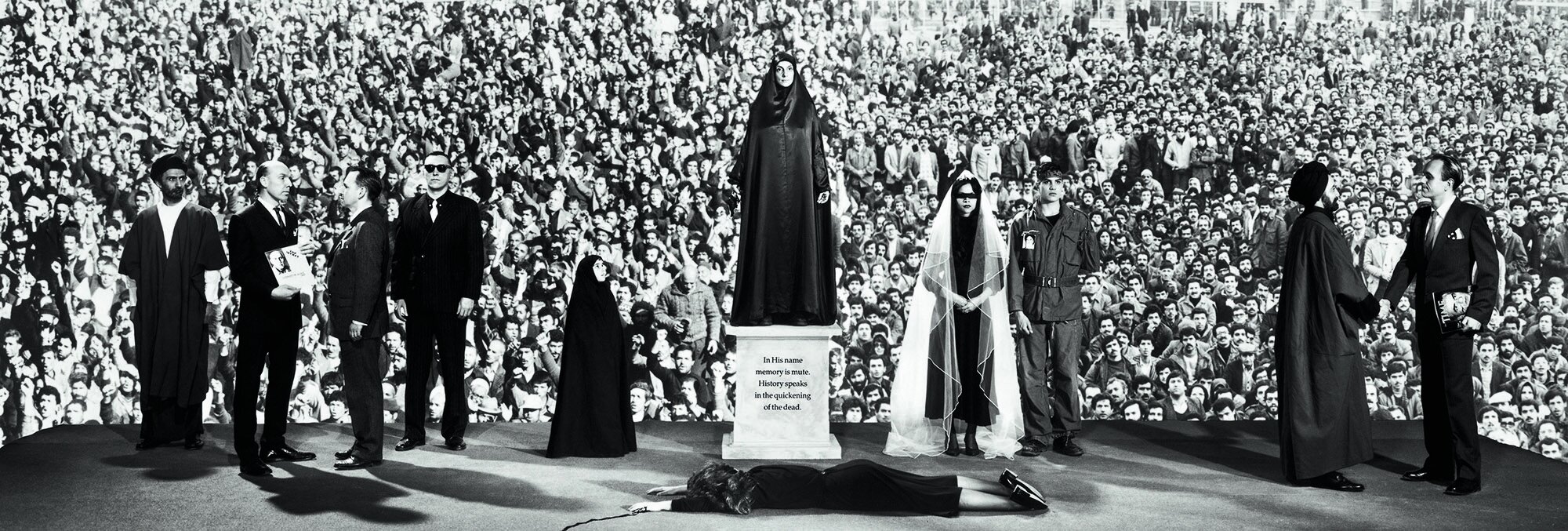

Mitra Tabrizian, to take one example from Reflections, resides in London. The artist’s second proof of Surveillance, 1990, a 20 x 60 inch black-and-white collage photograph, explores key moments in the formation of the modern Islamic Republic of Iran. Facing the viewer, instead of the million-strong audience behind them, ten people stand on a highly stylized stage. On the left, two men in Western suits come to an understanding, watched by a mullah, in a scene representing the U.S.–U.K. coup against Mosaddegh.

On the far right a cleric shakes hands with another man in a suit, symbolizing Khomeini’s 1979 return to Iran. In the center is an allegory for Iran’s eight-year-long war with Iraq. A woman is prone on the ground, face to the floor. Behind her, another woman in an abaya gazing off to the far distance stands resolutely on a plinth with these words: “In His name memory is mute. History speaks in the quickening of the dead.” In Surveillance, decades of Iranian history have been collapsed into a single frame.

Photography remains a medium of immense power and strange beauty in Middle Eastern art.

In the series Negative Incursion, 2002, Palestinian Rula Halawani (b. Jerusalem, 1964) printed the negatives of her photographs as “positives,” after an Israeli incursion into Ramallah. She explained to InVisible Culture’s Sherena Razek, “As negatives, they express the negation of our reality that the invasion represented.” Another artist, Kurdish Jamal Penjweny (b. Sulaimaniya, Iraqi Kurdistan, 1981) addresses a continuing legacy of violence and cruelty in his country of Iraq. For his series Saddam Is Here, 2010, Iraqis hold a photograph of the dictator’s face to their own. Is it an admission of victimhood or of guilt or has Saddam literally gotten into our heads, long after he’s gone?

The art in Reflections provides no easy answers, even in an artwork about family and love.

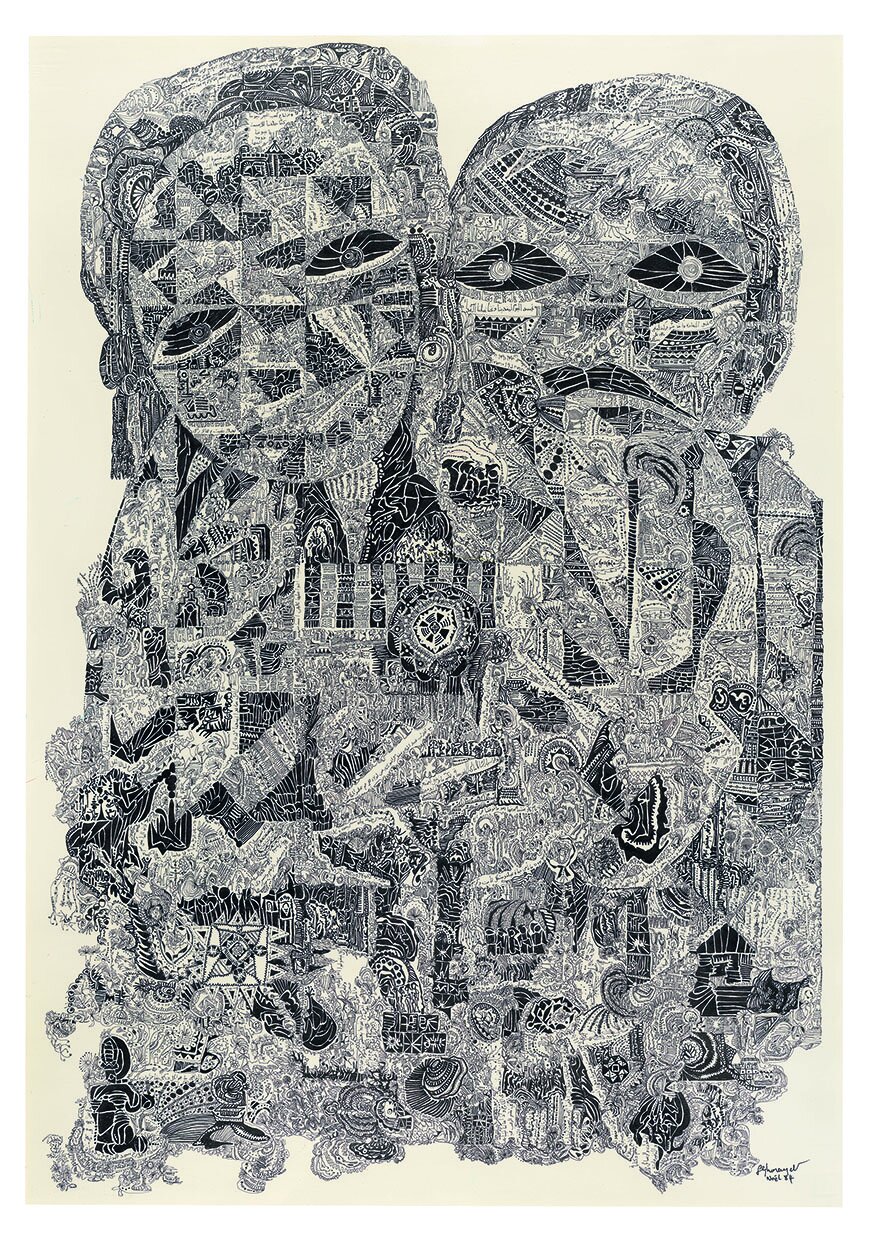

Two figures, a mother and daughter huddle together, their round expressive faces and bodies a landscape filled with tiny drawings and colloquial Arabic, the language of home. It is the story of 20th-century war in Lebanon. The conflict that has dominated the child’s life is the country’s civil war, inferred in the title of the pen and ink drawing, Already Ten Years, 1984, by Laure Ghorayeb (b. Deir El Qamar, 1931). The mother remembers fleeing with her own parents during the second world war and the aunts who starved to death during the first, so others could live.

The art in Reflections is unexpectedly beautiful even when it disturbs. The courage of the artists to remember, shock and create in original ways adds tension and urgency to their work. Even in the darkest art there are rays of hope. Reflections makes me want to see the British Museum’s contemporary Middle East and North African collection up close and in person—more so now because of the pandemic.