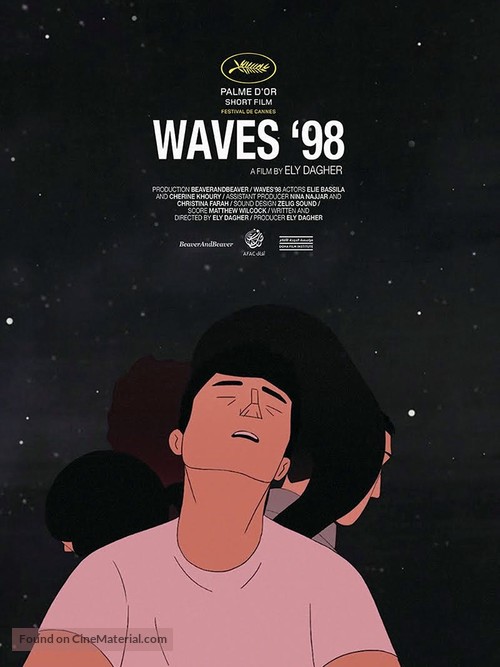

In the surrealist film Waves ’98, a young Lebanese man named Omar wastes away in Beirut’s segregated suburbs, in the late ’90s. Eventually, his disillusionment with post-civil war suburban life lures him into the city’s depths, where he slowly loses touch with reality as he struggles to maintain his sense of belonging to the hollow world around him.

Youssef Manessa

We open on the decrepit face of a sad, old man — slowly zooming in until an abstract current within him leads us into what looks like inner decay. Footage from an LBC broadcast is then screened, but before the anchor can deliver the news, it cuts to our protagonist Omar, on his bed, staring up at the ceiling as the news anchor drones on about the waste crisis.

A phone suddenly rings, but no one answers. No one seems to see a reason to. So it goes to voicemail over a montage of news footage and Omar’s drab apartment and disinterested parents.

The voice on the machine tells us:

“I’m tired of hearing the same story over and over again. It’s like everything’s stuck in a loop. I’m tired of my house, my bed. Tired of all these depressing stories. Everyone is fed up. They wake every morning to the same news, same chaos, and mess. Nothing ever changes. I don’t want to end up like them.”

As we’re hearing this, we don’t know who’s calling or what he’s referring to, but we don’t need to.

Anyone from Lebanon watching this knows exactly what he’s talking about.

Much has been said over the years about the complex relationship Beirutis have with their city. Gone are the days when the capital of this beleaguered nation could call itself “the Paris of the Middle East,” and in the aftermath of a brutal civil war, few, if any, were sold on the promises of the reconstruction era that vowed to restore the capital to its former glory. Now that peace has lasted for decades, a new generation of artists has emerged who were not conscious of the war but grew up in its wreckage, acutely aware that the promises of a golden age restored were frivolous lies. These lies were told and retold to us as our future was stolen right out of our bank accounts — leaving us with the empty platitudes of Mr. Lebanon and his neoliberal paradise that was always just a couple of years away.

Using a mix of animation, live-action footage, and photography, the Lebanese short film Waves ‘98 incomparably captures the deceptions and disappointments of the era in all its complexity and nuance, never offering us the simple solutions that we’ve become weary of as Lebanon spirals out of control. Set during the waste crisis of 1998 — an event chosen by its writer/director Ely Dagher as it was one of the few that affected everyone in Lebanon from all sects and both sides of the political spectrum — the film follows Omar, a Lebanese teenager wasting away in the segregated suburbs of Beirut, where his disillusionment with post-civil war life lures him into the city’s depths. There, Omar slowly loses touch with reality as he struggles to maintain his sense of belonging to the hollow world around him.

It’s not long before he encounters a colossal crystalline elephant in the heart of the dying city — the film panning up to it in all its glory, then zooming in on to Omar as he stares up at it in awe. For the first time, the screen is awash with warm colors, the allure of something so sublime irresistible in a place as miserable as Beirut. As Omar approaches the elephant’s snout, an opening reveals itself. When he looks to his side, he sees other youth jumping into other openings, but still hesitant, Omar balks at the opportunity…only for a beam of light to shoot out and pull him into the elephant.

And here, one stylistic choice sticks out.

Throughout the short film, a collage of animation and filmmaking techniques is used to meld the fantastical and the mundane — heightening Omar’s disorientation as he slowly loses touch with the reality around him. Notably, Beirut and its ever-present news broadcasts are neither animated nor even illustrated. Rather they’re depicted with footage and photographs of the real thing. Reality, it seems, must always be drawn from live-action footage and photographs just as the fantastical is only shown to us through animation.

Yet Omar and those around him are animated — just like the crystalline elephant is.

Perhaps, that’s what allows them inside?

But what happens inside the elephant is as mundane as the elephant is surreal. Omar is allowed to live out the life that Beirut prevents him from enjoying — the life he craves, being both beautiful and heartbreaking in its modest desires. What we are shown here is that the wonders of the unreal are our only hope when imprisoned by the listlessness of the real. But even though the elephant seems to be Omar’s only way out of the doldrums of Lebanese life, it is also an illusion that isolates him from the life he’s actually living and harms the world around him.

Hanging heavily and visibly over the city, the elephant isn’t the safe haven that Omar and other youth make it out to be. As it makes its way through the urban sprawl, it destroys buildings and damages roads until it can no longer sustain itself and collapses. Unlike the concrete that overwhelms Beirut, the elephant is made out of a fragile substance malleable enough to change and accommodate those it allows in — but that also means that it could fall apart at any moment.

Yet, in Omar’s eyes, both somehow coexist on the same plane.

What that means is only apparent when the crystalline elephant collapses onto the city after yet another news broadcast.

Not only is the elephant what Beirut isn’t, but it’s what Beirut could be…

One question lies at the heart of the film:

Who is the old man?

When we are first introduced to him, he appears to be some sort of apparition haunting our protagonist. But is he the kind of phantom that reemerges from our pasts?

Not quite.

We can’t be sure of whose speaking when we first hear the voice mail — only when the scene on the shore, later on, is serenaded with Omar’s musings that we finally understand that it was him all along. But then, at the end of the film, snippets from the voicemail come out of the old man’s mouth as he re-emerges from the darkness.

What is being communicated to us is clear:

The old man was once Omar. Omar may become the old man.

For the old man is not a revenant from Omar’s past, but a specter of the future he fears for himself.

And, when he and it finally confront each other, this is the phrase that the old man repeats:

“It feels like everything is stuck in a loop?”

This is where the cycle comes together. But will it loop or repeat?

Challenging and experimental, the film was unlike anything Lebanese cinema had seen up till the point of its release in 2015. What could’ve easily ended up an impenetrable mess resulted in a moving meditation on the post-war disillusionment of Lebanese youth — one prescient enough that, even though I was only three years old when the film takes place, I could’ve easily imagined it being about me or any of my friends growing up in Beirut more than ten years later.

And there’s something heartbreaking about that.

Though set in 1998, little if anything had changed when this film was released in 2015. Even though the filmmaker firmly establishes the time period he’s examining — going as far as to include it in the title — there’s something timeless explored here about the Lebanese condition. A condition that seems to be stuck in a loop, on repeat, endlessly. That’s why it comes as no surprise to me that Lebanon would experience yet another waste crisis only months after this film was first screened. Led by the grassroots organization “You Stink!”, protests took place throughout the summer, culminating in large gatherings that August that would spawn the political campaign known as Beirut Madinati. This initiative would historically garner more than 50% of the votes in the Christian district of East Beirut and more than a third of the vote in Sunni Muslim neighborhoods, signaling an unprecedented shift in the local political scene. These dwindling sentiments in the traditional post-war political class, coupled with a burgeoning economic crisis, collapsing infrastructure, and endemic corruption stirred up a revolutionary fervor unseen since the Cedar Revolution of 2005. Millions gathered on the streets of Lebanon, condemning sectarian rule and calling on the resignation of the Lebanese political elite who for the first time in decades feared the people whose lives they ran into the ground. It wouldn’t be long until Saad Hariri, the Prime Minister at the time, would resign, and the future that was promised to us by his late father seemed to be finally within reach…but the protests would not last.

Confronted by the vitriol of the people, za’ims (political leaders) sent thugs out into the street to aid the army in quelling the rebellion. It wasn’t long until a financial crisis — one of the worst in recorded history — would devalue the currency and eat up all of our savings. The Beirut Blast would soon follow only a couple of months later. By this time, the revolution was over and Saad Hariri would be designated Prime Minister again, only to fail to form a cabinet again only for Najib Mikati who had been Prime Minister twice before to take on another term. Again…

Naturally, those who could flee the country would, and those who were forced to remain, were now preoccupied with trying to maintain what little these za’ims — who took everything from us — had allowed us to hold on to.

This is not the first time the Lebanese have lost their savings, nor the first time that our currency has been made worthless by the careless fiscal policy of the financial elite. It is not the first time that Beirut has been ravaged, nor the first time in modern history that it has been decimated by an explosion. Years on from the waste crisis of 2015, we still haven’t even been able to clean up the mountains of trash from that time. These mountains loom large over Lebanon — larger every day, garbage piling on top of garbage, only for the structures to collapse in on themselves…then grow again with further accumulation.

This has all happened before, and alas, if history is any indicator, it will happen again.

Mr. Dagher is right.

Lebanon, it seems, is in a loop, endlessly reliving the same tragedies over and over again — the same news, same chaos, and mess. Nothing ever changes. There is little doubt in my mind that those of us left here such as myself, will end up like them.

And there’s nothing we can do about it.

There is a sense of entitlement in what we expect from art. We expect art to offer solutions to the state of affairs it explores, not just portray it in all its suffocating listlessness…but can it?

In the darkness, Omar’s eyes open again.

An opening from outside the elephant appears, shining light onto his weary eyes.

We see now that the crystalline elephant is suspended above the sea.

Omar stands on the ledge, the wind blowing against him, as the old man haunting him fades back into the darkness he came from.

The film ends with the camera slowly zooming out on the lone figure of the crystalline elephant hovering before the endless sprawl….

Does Waves ‘98 offer us, or in other words, Omar, a way out?

Not quite.

After it collapses, Omar wakes up in the elephant again, standing on the edge of the opening as it hovers above the sea — the dream behind him, the nightmare facing him — always facing him.

What will he do next?

Will Omar jump into the sea or head back inside?

Will the cycle break, or will it loop?

But, in the end, does it even matter?

In all of these options, there is no escaping Beirut.

For it seems that Beirut isn’t just a city. It’s a state of mind.

Watch the film here.