As Frieze London celebrates its 20th anniversary, we explore the Middle Eastern artists and galleries on display.

Sophie Kazan Makhlouf

The opening night of the annual art fair extravaganza Frieze in London may not have been full of the usual frisson and bounce as people juggled their oversized copies of the Frieze and Art newspapers, glasses of champagne and bulky catalogues, overcoats and umbrellas on a dark, rainy afternoon in Regent’s Park. However, for lovers of Middle Eastern artists, there were many bright beacons among the galleries at Frieze London and Frieze Masters.

At Frieze London, a massive and unmissable cutout sculpture, resembling a mythical creature, by the artist Walid Raad stood at the entrance of Beirut’s Sfeir-Semler Gallery. The gallery showed a broad range of artists and media in support of its many artists from across the Arab region. Raad’s enormous, I Long to Meet the Masses Once Again, 2019–2020, is made from wooden transport chests, assembled then cut to resemble a mythical Phoenix. The packing boxes no doubt allude to Lebanon’s Phoenician past and the transient nature of the region’s populations, many of whom have been forced to flee over the past 50 years or so, due to its civil war (1975–90), which is ever present in Raad’s work.

During the country’s bloody civil war, public monuments and the contents of its national museum were also stored in unmarked crates. According to the gallery, Raad’s work also criticizes, “the lack of a breakdown and reassembly protocol” of the museums which resulted in haphazard reconstructions and compositions such as this. The sculpture was a centerpiece for the artist’s exhibition at the Jesuit Chapel in Nimes, France, last year, where its wings made formidable shadow patterns of the floor and walls of the darkened French church.

At Frieze, the creature dwarfs the room and brings a surreal hyper-reality to the fair, together with Wael Shawky’s human and animal busts. These see Shawky reimagining identities and grotesque composite forms, using classical gargoyle heads being pecked by a bird of prey or assailed by a long-legged spider. Last year, Mounira Al Solh’s red Bedouin tent and A Day Is as Long as a Year installation at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead recalled the stories and experiences of war and displacement as told by women. Here at Frieze, Sfeir-Semler presents a very different series of work by the Netherlands-based artist that is no less powerful. Six embroidered squares, from Al Solh In Love in Blood series, appear humorous and endearing, using simple scenes of fingers holding tangled threads and children playing to represent or call to mind the emotions and conflict of daily life, particularly those of women and families in the Middle East. Al Solh works in a variety of media and these simple squares edged in colored silk offer a beautiful summary of her artistic range and skill.

Also at Sfeir-Semler is an artist’s book by the late Etel Adnan (1925−2021). Beautiful in its simplicity and linear style, it unfolds like a collection of lines and shapes in black Indian ink. Some pages written in red ink feature a traditional circular “cartouche” marking the end of each sentence, as was traditional in Islamic calligraphic manuscripts.

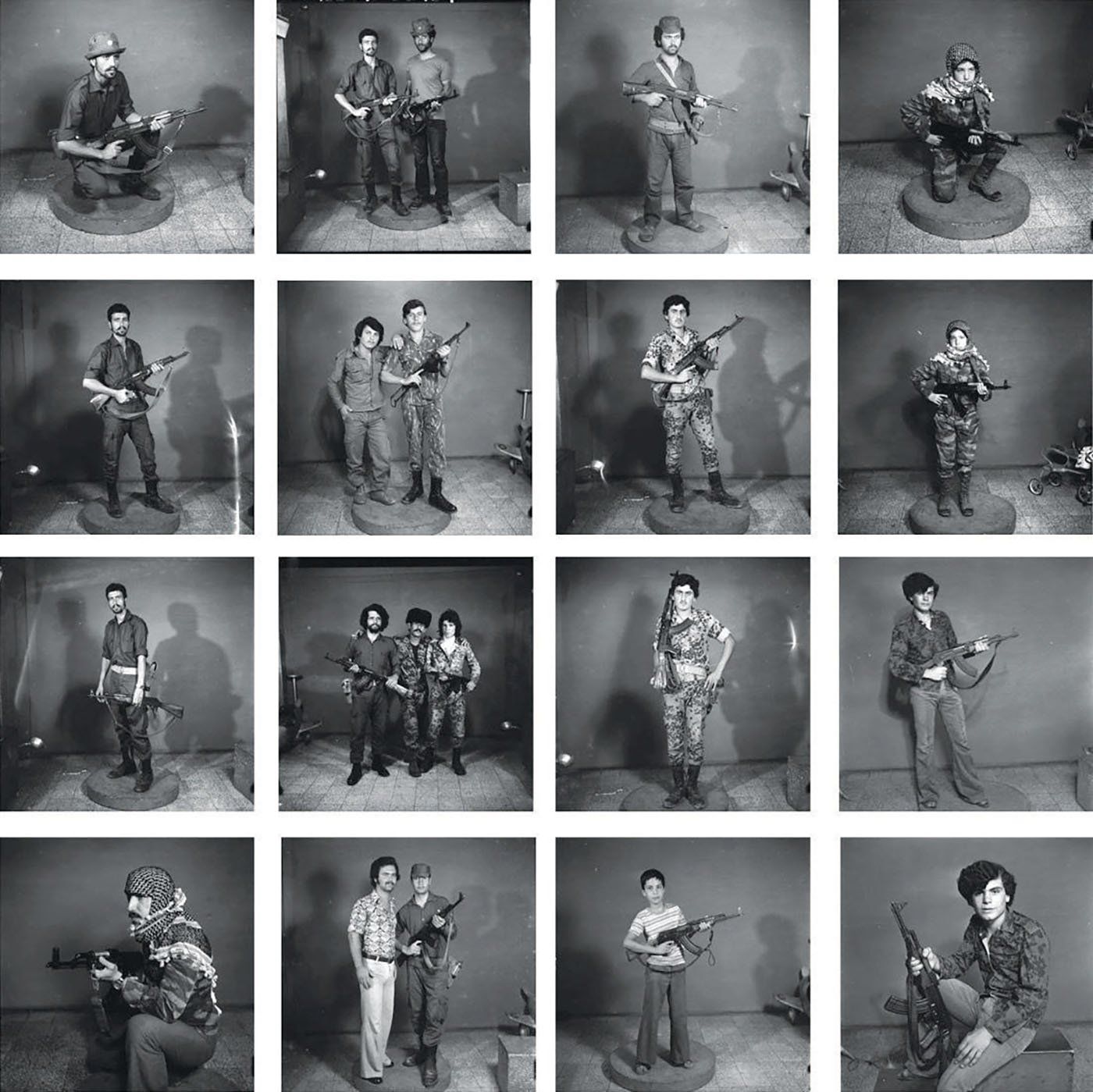

While the UK has been reeling from its recent economic downturn, the socio-economic and political way of life in Lebanon seem to have gone beyond social commentary. The work by the acclaimed artist and photographer Akram Zaatari is particularly chilling. Along the outer wall of the Sfeir-Semler stand, facing one of the fair’s main thoroughfares, are large photographs of young fighters, dressed in army fatigues and brandishing their automatic weapons. Salvaged from the archives of studio photographers from around the Middle East, Zaatari deconstructs the images of young men with scruffy haircuts and camouflage, most under the age of 20 years old. Zaatari has carefully scraped the guns out of the image just enough to draw the attention of the viewer to the extreme youth of the boys and their polite and patient poses for the studio photographer.

Maria Sukkar sits on several acquisition committees for major London museums such as the Tate Gallery, the British Museum and the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA). She was particularly impressed by Paula Yacoub’s photographs from the Marfa’ Gallery in Beirut. These photographs depict water after it hits a solid surface and splashes or glides along a fountain’s edge. Yacoub works are investigative and structured and her two waxworks, one laser copied wax (Mist Shatila, 1995) the other a delicate wax and paper arrangement (White Pile, 1993) develop the artist’s exploration of the shape of liquid, as it changes into a solid.

In the main hall of Frieze London, the AlUla and Jeddah-based Athr Gallery’s offering was unexpected. The stand had been divided into two parts in which on one side and in a nod to traditional views of Saudi Arabia, a display of photographs by Sultan bin Fahad shows the opulent life, clothing and dress of the Saudi royal elite. A gold rimmed dinner service, complete crystal and colored glass are posited nonchalantly atop a dining table (Dinner at the Palace, 2019) and beside it are photographs from Untitled 1, 2 and 4, 2020 as well as other surveillance style photographs and videos that deconstruct Saudi cultural life.

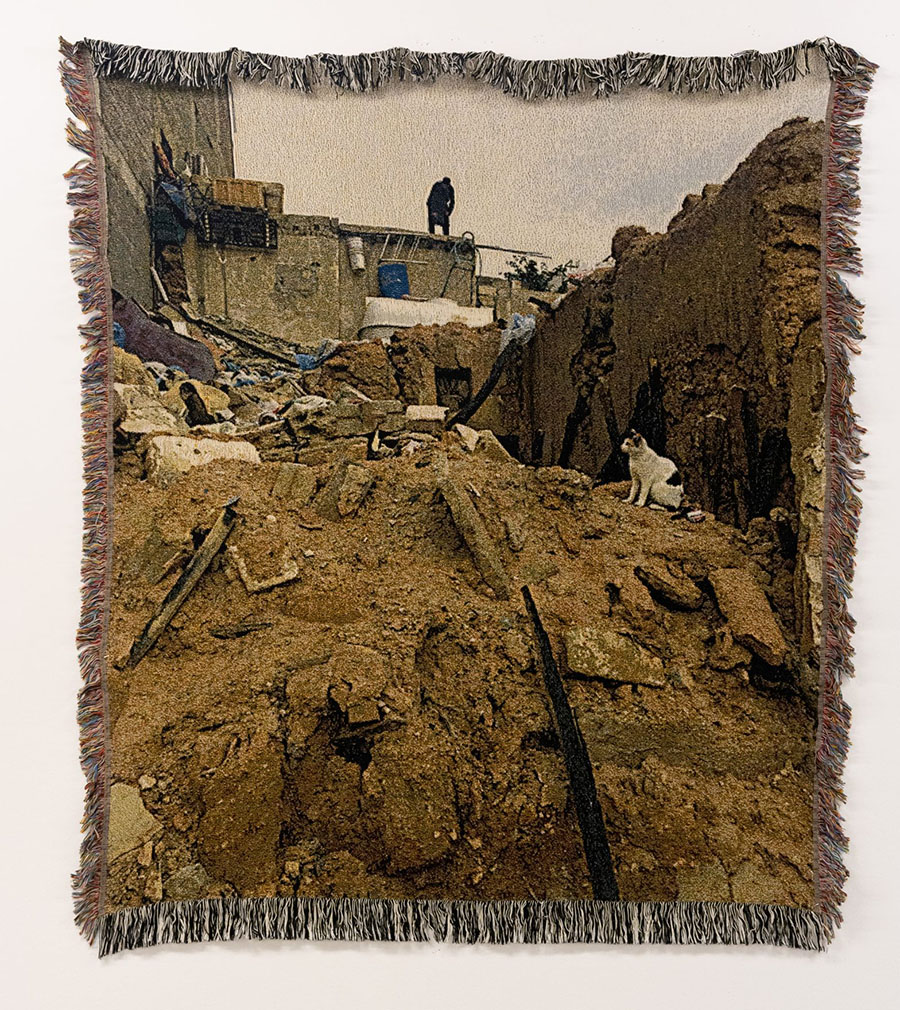

On the other side of the stand and in stark contrast are thick, woven cotton blankets by the artist Sarah Abu-Abdallah. No doubt referencing the ever-present use of carpets in the Gulf and throughout the Arab world in a domestic and prayer environment, Abu-Abdallah’s blankets depict more candid aspects of daily life. One seems to portray the contents of her fridge with sliced bread and plastic wrapped tomatoes carefully displayed in a mindful way that is starkly contrasted by the haphazard piles of priceless tableware in bin Fahad’s installations nearby. Another features an abandoned urban landscape with its broken-down buildings and streets creating a sense of isolation and loss. Perhaps the two artists’ work communicate the new Saudi Arabia, which recognizes difference. As a woman from a non-royal social status, Abu-Abdallah’s work is an interesting exploration into a very different, non-glamorous side of Saudi contemporary life. This is surprising and also somewhat exciting.

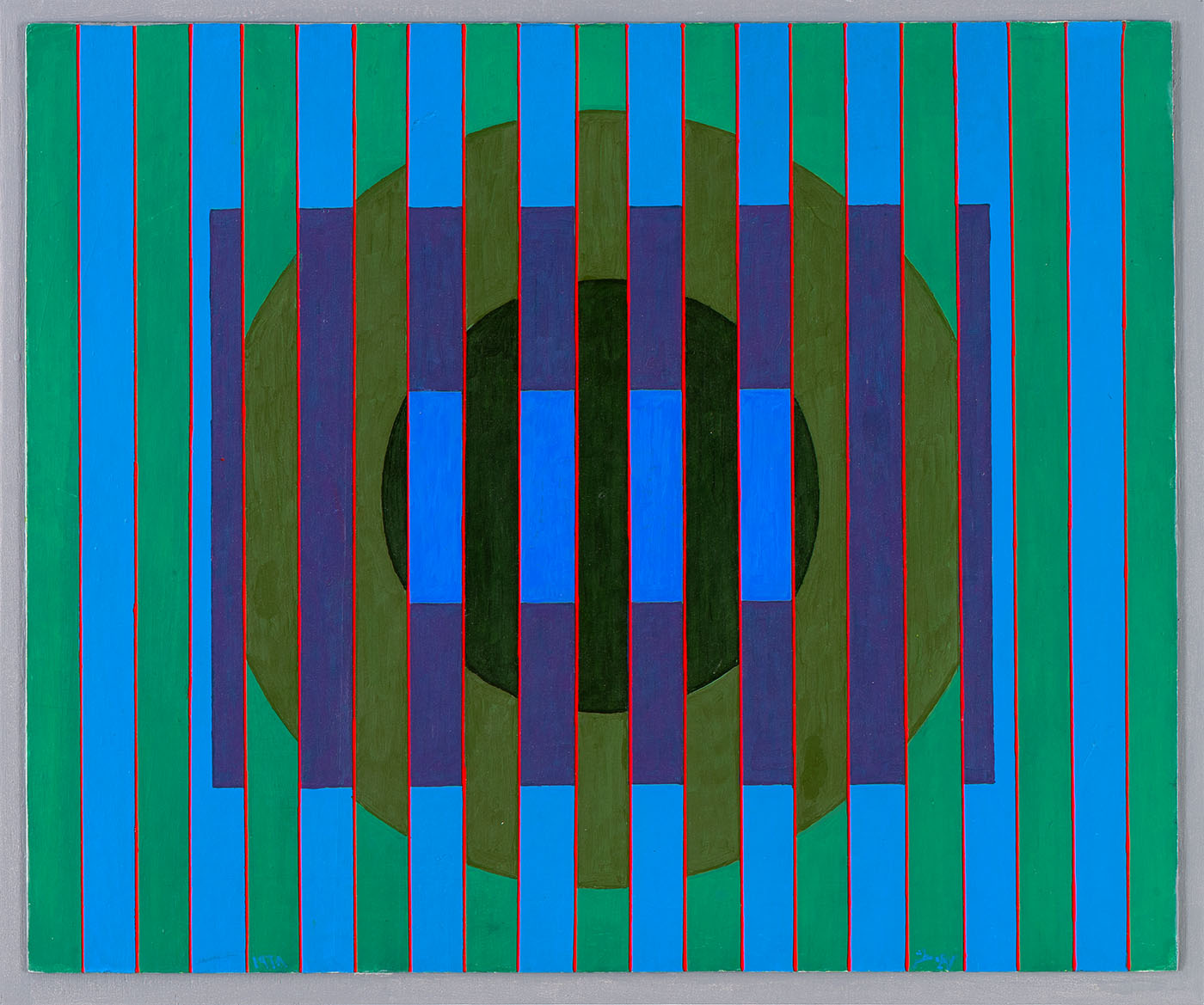

Moving into Frieze Masters, with its emphasis on historic art, Dubai’s Lawrie Shabibi Gallery deserves a special mention. The gallery presented work by Iraqi artist and contemporary painter Mehdi Moutashar. His work is extremely versatile and geometric though abstract; his colors and lines reach out from the walls.

Gallerist Asmaa Shabibi had only praise for the art fair, “Frieze was brilliant this year. We met some very good collectors and had a lot of discussions about geometric abstraction: Le Parc Carlos Cruz-Diez, Jesus Rafael Soto … Everyone was delighted to discover a new artist and [was] also surprised that an Iraqi artist was doing this sort of work. One curator told me that this was one of the best works by any Iraqi artist he had ever seen! Overall Moutashar had an amazing response.”

Middle Eastern art expert and former Sotheby’s Deputy Chairman, Roxane Zand told me it was heartening to see more Middle Eastern collectors attending the annual art fair, and she felt that this had been encouraged by the new Frieze 91 membership program, which was launched in 2021. A members-only community devoted to sharing art from diverse communities meant that many of the fair’s exhibitors were also taking part in more talks and lateral events this year.

While Lawrie Shabibi was a hit among many collectors, another highlight at the art fair was White Cube’s presentation of the legendary artist Mona Hatoum, curated by Sheena Wagstaff as a “studio” space. This allows the viewer to explore a range of Hatoum’s work in all its variety and intensity. Wagstaff uses glass cases to display recognizable and beautifully formed hair balls from the 1990s, balanced precariously beside cases, cages, henna prints, conjoined coffee cups (T42 (gold), 1999) and “eye-catchers” made of bamboo, stainless steel and fishing wire. A provocative triangular pile of hair is positioned on the seat of a wooden bistrot chair (Jardin Public, 1993) in the corner of the stand and a recent work comprised of puddles of red hand-blown glass that appear to be caged within tall stainless-steel enclosures (Cells (tower), 2023). It is refreshing to see an artist’s work displayed in a way that shows the trajectory of their work and allows viewers to appreciate recent works in context. Hatoum and her art remain undisputedly irreverent and questioning as ever!

Frieze London and Frieze Masters took place from October 11 to 15, 2023. The first Frieze art fair took place in London, in 2003. The first Frieze Los Angeles was held in 2019 and Frieze New York appeared three years later. In 2022 was the first edition of Frieze Seoul. The Korean capital welcomed the fair for the second time this year.