Eman Quotah reviews a new anthology of love poems of Arab poets writing in English, either in diaspora or in their home countries — many of whom are born in 1980 or later. “That overwhelming youth reflects more than patterns of Arab migration to Anglophone countries.”

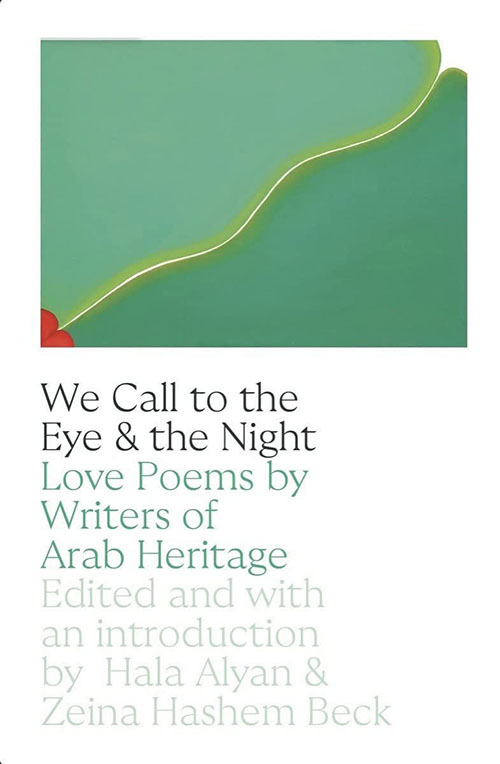

We Call to the Eye & the Night: Love Poems by Writers of Arab Heritage

Edited by Hala Alyan & Zeina Hashem Beck

Persea Books 2023

ISBN 9780892555673

Eman Quotah

At the college I attended, one poetry professor famously asked students to, “Write a happy love poem” as their first assignment in her poetry-writing class. Most students considered the prompt tricky. Writing about unrequited love, unhealthy ardor, broken hearts, and failed passions seemed so much easier to jaded 17- to 22-year-olds than writing about love that completes us and bathes us in contentment.

But of course, love poetry offers more than two registers; experiences of love encompass much more than happiness and sadness. In their new anthology We Call to the Eye & the Night: Love Poems by Writers of Arab Heritage, editors Hala Alyan and Zeina Hashem Beck have assembled poems that tackle a striking range of leitmotifs: desire and betrayal, heartbreak and healing, passion and possession, crushes and obsession, beginnings and endings, lust and loss, butterflies and self-doubt, steadiness and serendipity, nostalgia and regret.

In Hedy Habra’s “The Camisole,” the feel of silk fabric suggests yearning for a lover who may or may not arrive. In Rewa Zeinati’s “the ways we learn about love”—which begins, “Mother wants to break father/in half”—we learn the origin story of traumatic familial love. Marlin M. Jenkins’ rollicking and humorous praise poem “Ode to my Uni-brow,” centers self- and ancestor-love in a world that does not guarantee either.

Jenkins, who was born and raised in Detroit to a Black father and Lebanese mother, writes,

… praise to the hairiness my Lebanese

family shares, praise be to owning what may keep

the TSA’s eyes on us, though god-willing not their hands

(and fuck the TSA while we’re at it), and praise be

to pride and to the Muslim man at the gas station

who asks if I am Muslim, too, and though I am not, praise

to being seen as a brother …

Featuring work by dozens of living writers with Arab roots — both those living in diaspora and those living in the lands of their origin — We Call to the Eye & the Night was conceived by Alyan and Hashem Beck as “a record of and a tribute to some of the wonderful Arab-heritage poets writing in English today.”

Some contributions, like Jenkins’, wear identity on their sleeves and others do not, a testament to the diverse ways contemporary poets lean into their Arabness or choose not to, in individual poems and in their work as a whole.

Diving into the book, I wondered if its focus on love was truly central or merely incidental — a way to streamline the selection of poems.

As the editors explain in their introduction, they quickly agreed, over WhatsApp, on their theme. “We were both at moments in our lives that called for the sustenance of love poems,” they write.

Although, or because, the anthology’s authors are all poets of Arab descent, Alyan and Hashem Beck refuse to draw a line between “Arabness and love,” or between who is in the anthology and what they are writing about.

“Yes, we realize there are endless expressions and words for love in Arabic … but we’d be forcing it, pandering to an Orientalist gaze, if we proselytized about love and Arabic,” they write.

Their instinct not to pander is noble and correct. But in their succinct (just a page and a half) introduction, the editors miss an opportunity to contextualize the contents of the anthology for the reader: Why this group of poets, why now, and why love poems?

Not out of a need to justify their decisions — it’s fine for editors to publish what they want and what they personally love. But rather as an attempt to put forward a unifying theory about the power of the love poem in the hands of these specific poets, a theory with which the reader may agree or disagree but might serve to guide their reading of this eclectic collection.

Naming We Call to the Eye & the Night a book of love poems (rather than poems about love) does more than suggest a theme; it suggests a connection to poetic tradition. Love poetry’s family tree, in both Anglophone and Arabophone literature, casts a large shadow. Its many branches stem from the poetic traditions that have influenced English and Arabic verse over centuries (French, Italian, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Persian, Urdu, to name a few).

In her ghazal “A Lover’s Quarrel with the World,” contributor Deema K. Shehabi writes,

History gallops over the margins of your page, what’s a story, but its plural all over the world?

Arabic lulls ageless in your ears, but to you what most matters is temporal in this world.

The Sheikh with a gold pen in his pocket, the girl lathering her father’s head with musk

And you—pearling over Whitman’s poems—all have a lover’s quarrel with the world.

It would not be Orientalizing or essentializing to point out that the ghazal form Shehabi employs, an important and beloved poetic form in English today, wended its way to Anglophone poetry from Arabic via Urdu. In Arabic, the ghazal is a poem of love; the word derives from a root that can mean “to flirt.”

And it would not, I think, be explaining too much to discuss how love poetry’s lineage in Arabic brings to mind, say, Darwish, Adonis, Nizar Qabbani, Qays wa Layla, Umm Kulthum’s interpretations of Ahmed Rami’s lyrics, and even the elegies of Al Khansaa. Or how the love poem’s roots in English are firmly planted in, for example, poets as varied as Shakespeare, Walt Whitman, E.E. Cummings, Adrienne Rich, and Sylvia Plath, not to mention translations of Sappho and Rumi, to name just a few predecessors.

Each poet in this anthology, to be sure, writes from and within their own idiosyncratic literary heritage. But readers’ understanding of many of the poems can deepen if we are given an opening to see how the poets simultaneously root their verse in established traditions of love poetry while carving out new ones.

For example, Mariam Gomaa’s provocative “Tell My White Boyfriend I Will Always Leave” is a love poem to an imaginary, fleeting lover, an Arab man who is “all nose, thick lashes, stubborn hair—/who in the sunlit afternoon will call out ya’3asal.” It’s a poem about leaving — and the constant threat of loss that comes with any love — that is also about staying true to double-edged cultural expectations and oneself. Gomaa writes, “When I reach for him, I reach for everyone/who loved me once.”

We Call to the Eye & the Night doesn’t claim to define the modern love poem. And it’s definitely not — and I mean this as a compliment — a book from which engaged couples might easily select readings for their wedding ceremonies. For good or for ill, the burden of supplying love poems for Western weddings remains firmly on Rumi’s broad shoulders.

Instead, as Alyan and Hashem Beck intended, the anthology works well as a roll call of some of the exciting Anglophone poets of Arab heritage writing and publishing now — in numbers far greater than there were just a decade ago. While I was familiar with the work of many of the poets here, a few others were new to me. Collected in one volume, the poems create a lively conversation, whether one reads them in order or by dipping in and out of the book.

Take the concrete poems “Ananas” and “Qalb,” respectively by poets Hajer Almosleh and Silvia El Helo, who use the limitations of the shapes they’ve chosen to very different ends. Almosleh’s pineapple, though prickly, comes to define romantic love. El Helo’s modified heart shape distorts memory and feeling.

Based on the birth dates in the contributors’ notes, I estimate that about three-quarters of the poets were born in 1980 or later. That overwhelming youth reflects more than patterns of Arab migration to Anglophone countries. Because of the spread of English-language media and the Internet, we’ve also seen, over the past decade or so, more non-diasporic Arab writers writing in English. The past five to 10 years have also brought sea changes in Anglophone literature and publishing — which, while it remains very white, has shown greater interest than ever before in nurturing, publishing, and championing Arab writers.

Anthologies of Arab writing in English published in the early aughts and the 2010s exclusively featured Arab Americans or a mix of Anglophone and translated work. Today, editors like Alyan, Hashem Beck, and Elias Jahshan of This Arab Is Queer can bring together a large number of writers of Arab heritage from all over the world who write primarily in English.

But what makes putting Arab-heritage writers in a volume together necessary or compelling?

For me, the answer comes from an open mic I attended last year in Dearborn, Michigan, following the Arab American National Museum’s Arab American Book Awards ceremony. Attending with my husband and kids (then ages 11 and 14), I wondered what they would think of the format. At open mics in the past, I’d heard both amazing poetry and some real clunkers.

I shouldn’t have worried. The level of excellence was high in that room full of mostly people of Arab heritage. Every reader and musician performed from the heart, creating a pitch perfect, beautiful, and thrilling celebration of Arab and SWANA voices and community in the English-speaking world.

We Call to the Eye & the Night feels as affirming as that open mic. The book does not attempt to survey living Arab writers, as past anthologies have done. (See: Post Gibran: An Anthology of New Arab-American Writing, Inclined to Speak: An Anthology of Contemporary Arab American Poetry, Dinarzad’s Children: An Anthology of Contemporary Arab American Fiction, and Nathalie Handal’s classic The Poetry of Arab Women: A Contemporary Anthology.) Instead, Alyan and Hashem Beck have invited writers to an open celebration, a haflah or ’azumah, a place where they can be with other writers with whom they have this one thing in common, and to whom they don’t have to explain themselves. Where they can be themselves on the page, with no expectation that they will “perform their identities and otherness,” as, the editors say, writers of Arab heritage are often asked to do in an Anglophone publishing scene.

Where they can write about love, a supremely human and universal topic, however they want to.

As Leila Chatti writes in “While You Are Shaving, It Rains,”

… I have come four thousand miles

To love you better. …