Memory Box is the latest film by Lebanese artist duo Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, bringing together years of artistic experimentation, personal archives, and research on the production of images from the Lebanese Civil War. The film was the first motion picture to represent Lebanon at the 71st Berlinale in four decades.

In limited VOD and in theatres as follows: Louvre, Paris, June 19 • Lebanese Film Festival, Ottawa, June 20 • Soeurs Jumelles, Rochefort, June 22 • Beirut Cinema Days, July 3rd • Zawya Cinema, Cairo, from July 15th • Walker Art Center, September 28th • Mizna Arab Film Festival, Minneapolis, September 28th-October 2nd

Arie Akkermans-Amaya

Memory Box (2021), the most recent cinematic effort by Lebanese filmmakers and artists Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, is a film rich in imagery about the Lebanese Civil War. But violent conflict is not its central theme. Ultimately, it is a film about the transmission of memory across generations, what happens when memory becomes interrupted, and the lengths that people go to in order to either restart or halt this process. The plot is deceptively simple:

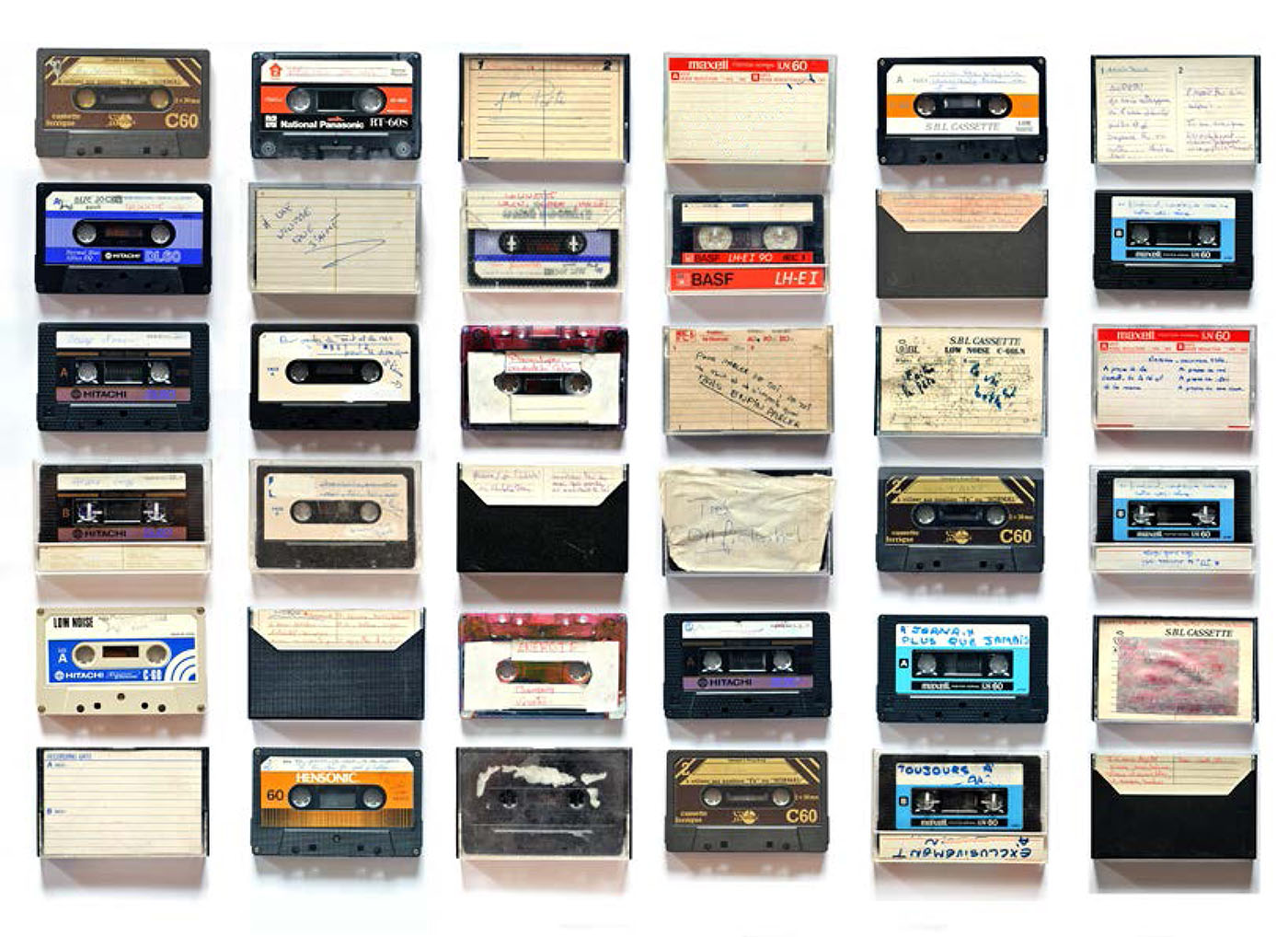

Set in present day Montreal, a teenage girl, Alex (played by Paloma Vauthier), lives with her mother Maia, and grandmother, affectionately called Téta in Arabic. On Christmas Eve, a mysterious delivery arrives, it’s a box containing Maia’s notebooks, tapes and photographs sent during the war years to her childhood friend Liza in Paris. But both Maia (played as an adult by Rim Turkhi) and her mother (Clémence Sabbagh), are afraid of the painful memories that the notebooks might reveal, and they forbid Alex from looking into the contents of the box.

“The bombing lasted all week. We had to flee the school.” This is what Maia Abboud (played by Manal Issa), the teenage protagonist from Beirut, tells her friend Liza Haber, in June 1982, in a recorded tape that traveled from Lebanon to France, alongside the notebooks, letters and photographs that capture that moment in time. We know the larger events of 1982 — the siege of Beirut which took place in the summer that year, resulting from the end of a ceasefire previously brokered by the United Nations. The ring around Beirut closed in by June 13th, a week after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, as the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Syrian forces were isolated inside the city. Maia’s narration continues: “That night, things went wild. The city was in flames. Shelling and fires, like in a movie.”

Soon thereafter, the city can be seen from above, in blurry archival images, beset by explosions.

However, this story is both less and more than a fiction, as some of the notebooks originally belonged to Hadjithomas. She offers us details about this mysterious archive and the role the notebooks played in the making of the film:

“It all started when I retrieved notebooks, letters and audiotapes I sent to my best friend in the 1980s. She had to leave Lebanon with her family, because of the Civil War and I stayed there. So, we promised to write to each other every day. And we did so, every single day from 1982 to 1988. And then at some point, we lost contact for more than 25 years. Then, one day, she came to the opening of one of [mine and Khalil’s] exhibitions in Paris. We met again and decided to exchange our notebooks. Suddenly, I had, in my hands, all these incredible stories I had forgotten. I read and listened to everything. Our daughter, Alya, was then my age when I wrote to my friend, wanted to read them. Khalil and I thought that it was not a very good idea for her to do so, but we immediately saw the possibility of a film.”

Predictably for the plot of a film, Alex decides to dig in, and the notebooks reveal to her a world that had remained hidden until then — the intoxicating years of the war, both exhilarating, and terrifying. She reads and hears about her mother’s first love: “This is the best day of my life.” Her mother Maia and her grandmother [Téta] had kept all the details about their past in Lebanon a secret. This unlicensed expedition into the past leads to an inevitable confrontation with Maia, in the aftermath of which there’s truth-telling, reconciliation and eventually a journey back to Beirut, in order to attend a mass in memory of Maia’s friend Liza, who has died in the interim. It’s also Maia’s first confrontation with the ghosts of the past, and the details are too beautiful to be written down here, they must be left for the viewers of the film to discover. However ordinary this plot might seem (other Lebanese films adopt a similar narrative technique), or how accessible it is to an unprepared viewer, it is yet the elegant visual storytelling of Hadjithomas and Joreige where the real magic happens.

On Directors Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige

As contemporary artists, Hadjithomas and Joreige have spent the last two decades excavating Lebanon’s recent memory landscape inside out—across cinema, photography, archival research and multilinear narratives drawn from archaeology, literature and politics, and Memory Box is replete with subtle references to their previous works. When Alex begins to unpack her mother’s secret correspondence, she gazes incidentally upon what seems to be nothing but a contact print from an analog camera roll, containing nondescript images of the destruction in Beirut, as Maia tells her faraway friend: “Beirut is so destroyed… Liza, you wouldn’t recognize it”. The print is in fact a section from one of Hadjithomas and Joreige’s early semi-architectural photography series, The Archaeology of Our Gaze (1997), shot from the debris of buildings in Beirut, in an attempt to process fragments of a postwar city when the context has gone missing and the viewer can no longer recognize the original source.

Their engagement with archaeology starts out in this series of semi-architectural photographs, but continues in the following decades with larger narratives, such as the complex processes of archaeological timescales, or the relations of continuity between the ancient past and the political present. Yet, what the artist duo is searching for in archaeology—which immediately connects with the process and medium of their latest film, is not necessarily the past, but new possibilities on how lived time can be described, narrated and recorded. Khalil Joreige tells in an interview from 2012: “Archaeology here is interesting in the way that it forbids you to give any definition of a place because it is structured in time across different times.”

Flocks of birds fly in slow motion across a pristine blue sky, suddenly interrupted at night by the sounds of fire. These poisoned images blend with one another, and cross temporalities, while personal memories become estranged from one another. The carnage of war is too brutal here to be treated à part in aesthetic terms. This violent world is above all one of suffering, beyond any redemption.

In a recent conversation from Beirut, Joreige told us about the relationship between personal archives and cinema in their work: “We often start from something very personal to us, from our own archives, or from an encounter, and then we start researching. In [the film] A Perfect Day (2005), it was the story of the kidnapping of my maternal uncle who is one of the 17,000 missing persons in Lebanon who never returned. And in I Want To See (2008), it was our reaction to the July 2006 war between Israel and Lebanon, and the question of what images and cinema can do in these moments. Here we had extraordinarily detailed material. We were interested in making it into a fiction because we had to get away from the personal aspect of it. We decided to work with a scriptwriter who did not know Lebanon, and who had never lived through a civil war. Multiple axes were of our interest: the transmission between three generations and in parallel, yesterday’s correspondence with today.”

Referring to Memory Box Joreige continued, “The notebooks are seen through Alex’s eyes, a young girl who reinterprets the life of her teenage mother between imagination and reality. To do this, she relies on photographs, most of which I took in the 1980s in Beirut and the 10,000 photos we had to take for the film, in order to reconstruct everything. We wanted to add a visual dimension based on the photos I had taken in the course of my adolescence in Beirut, during the same timeframe. We each had expressed ourselves through the medium of our choice available at the time, through our individual passion. It seemed important for us to establish the same dialogue. We combined the two archives, our two stories.”

In this confusion of images from the present mixed with memories from the past, remembrance can become unstable. Yet the vividness of young Maia’s world, a chaotic universe of violence and disaster, punctuated by love and dreams, by pop music and friendship, is constructed with such intensity of experience that the temporal distance from the viewer breaks down, and you can almost taste a chronic despair mixed with unending desire.

Maia shares her traumatic experience, which culminated in an escape to Canada via Cyprus, with her daughter: “From that point on, I don’t know. I can’t remember. I don’t really remember things. Sometimes I feel that I reinvent things. I don’t know what’s real or false.” Young Maia, obsessed with photography, snaps her last picture of Beirut from the distance, on a ship to safety: “And my world vanished forever.” Yet a dark secret remains untold.

The artists’ previous films about Lebanon reappear in Memory Box as visual or textual quotations, creating a thread of continuity over time. While recounting her final years in Beirut, Maia utters the following sentence: “We were all looking for something we’d lost.” This is paraphrasing directly from A Perfect Day (2005), an elegiac film about intentional amnesia and lost love. A number of visual allegories reappear here as well from other films: fleeting lights signalling reconciliation with tragedy or the long shots of the Beirut corniche, symbolizing open-ended hope. The artist Rabih Mroué, protagonist and narrator of I Want To See, returns to Memory Box, in the similarly enigmatic role of Raja, the long lost love of Maia’s youth.

The transtemporal knots between different junctures of Hadjithomas and Joreige’s work, their archives, cinematic eyes, and conversations with others, are so many that they cannot be mapped out accurately, without falling into a circle of confusion—the title of an earlier photographic work of theirs, reading Beirut as a body that is in perpetual mutation and movement.

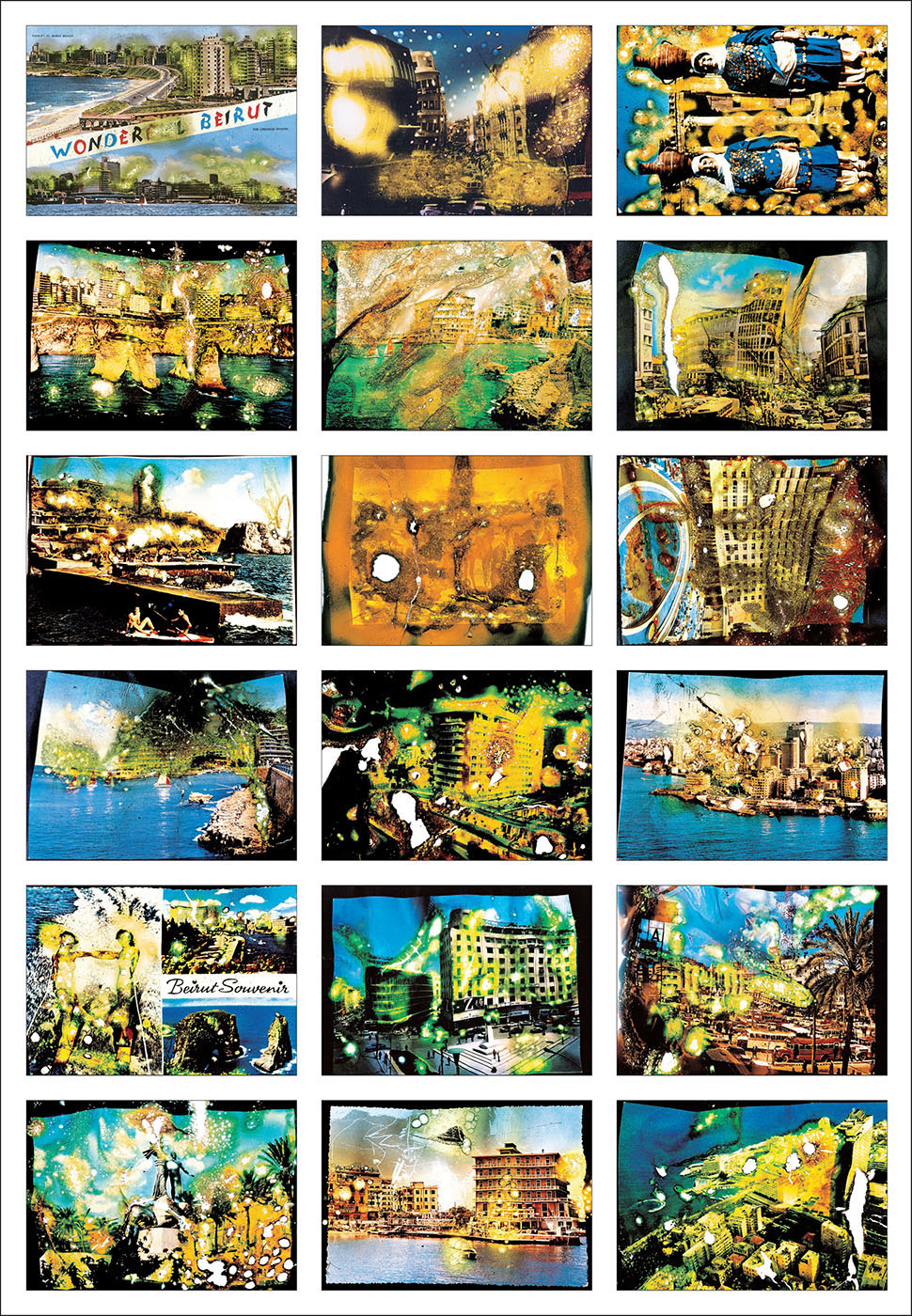

For those familiar with their work, one of the most fascinating narrative moments in Memory Box is the animated scenes, in which the photographic images of Maia’s Beirut, become slowly burned on the edges, as the war begins to slowly consume the city. I believe this is a reference to “Postcards of War” (1997-2006), part of the project Wonder Beirut, consisting of a selection of touristic images of Beirut taken between 1968 and 1969, by a fictional photographer, portraying the Beirut Central District, the Lebanese Riviera and its luxury hotels; an idyllic, glamorized idea of Lebanon in the 1960s. The images were then burned by the photographer himself between 1975 and 1990, following the shelling and destruction caused by the war in these locations. These burned marks represent, once again, the potential collapse of historical imagery, their potential obsolescence.

However, the topic of transmission from grandmother to mother to daughter is indeed the most crucial aspect of the film. Each of the three tells her own story but at the same time weaves into the others. Following the cycle of life, one allows the dead to take the place of the living, and the other way around. In this process they become able to see through each other. But what happens to this transmission when the chains of images, meanings and experiences that create bonds have been torn apart? If the image loses its focus, and its context becomes ambiguous or goes missing, the bond cannot be reconstructed.

Yet images and personal stories are not a series of freeze frames, and this is where the process of transmission that Joreige told us about, encounters his idea of archaeology: According to contemporary archaeologists, every site is the accumulation of continuous activity, with each event partially or wholly erasing traces of earlier events. Thus, our present is always replete with pasts mixing and folding together. Gérard Chouqer coined the neologism transformission, to refer to the mutually constitutive and simultaneous process of transmission and transformation. Transmission as transformission means for us here, that the past is not a fossil abandoned to empty time, but something that is actively modified and changed over time, while it simultaneously gives structure to our present selves.

Near the end of the film, when Alex and Maia arrive in Beirut, the grandmother calls on the phone and tells her granddaughter: “Alex, listen, sweetheart, take photos of Beirut for me and of the sun too. Don’t forget the sun!” This otherwise casual request would go unnoticed, except that the sun is a central figure for Hadjithomas and Joreige. It is at the very heart of their ongoing project “I Stared at Beauty So Much.” The sun was also a central feature in one of their major exhibitions, “Two Suns in a Sunset” (2016), first shown at the Sharjah Art Foundation, in which they moved away from the literalism of political narratives and positioned themselves towards the light, towards the sun, and began to speculate on other possibilities of history: Would it change if we narrated it differently? Can poetry help us make sense of disaster without radical defeat?

Hadjithomas told me in an interview we did at the time in Dubai: “When you superimpose so many temporalities, so many images, little by little, there is a kind of duplicity, so you have many suns appearing. Things were happening to some people; this idea of multiple suns when you feel this chaotic time. It’s not only what’s happening to men; it’s affecting nature, it’s affecting the universe, and it’s affecting everything.”

The sun is the deciding element in the plot resolution of Memory Box but it doesn’t bring any closure — it is just the remote possibility of light that stands in its place. In between so many apocalypses and disasters, Hadjithomas tells us now in recent conversations where the multiple suns have gone six years later:

“We finished shooting the film in May 2019, and started editing it in the midst of a revolution, in the autumn of the same year. A revolution against the corrupt and criminal leaders and against the banking system that has taken the Lebanese people hostage. Of course, this resonates in a tragic way, like a terrifying mirror, with many pages from my notebooks that are quoted in the film and which echo the violence of the war, the current devaluation of the Lebanese pound, the insecurity, the despair and the systemic collapse of the country; the temptation and sometimes even the terrible obligation of exile. And then there’s the tragic explosion of August 4th, which destroyed a third of the city, and a part of our lives. Everyone feels all the more strongly belonging to cycles of destruction and reconstruction, a perpetual cyclical motion. The film’s ending, with the idea of the sun setting and rising again, and thus the start of new beginnings, bright moments alternating with dark ones. But there’s something permanent, unchanging, like a cycle, after each catastrophe, there’s a regeneration. After each disaster, perhaps one can hope for a renewal. You can see the sun setting or rising. It’s a continuous cycle.”

Upon her return to Beirut, Maia is faced with a Beirut that is new—the central district has been reconstructed and in the process, her family home has vanished to make place for a luxury building. We as viewers know that it is also just about to be destroyed once again. And through this conspicuous knowledge, the light of the sun becomes doubly haunting. It’s almost as if we don’t want to see it, as if we don’t want to accept that this beauty is possible at all. But in spite of the redemptive promise of this metaphor, Maia doesn’t find closure—her home has been destroyed and they’re unable to locate the graves of her father and brother in the cemetery. Maybe it’s better to not find closure at a time like this, before another fall? Yet, the artists remain convinced of the power of human encounters.

Hadjithomas concludes our most recent conversation:

“The end of the film appears since then as a dream, a kind of science fiction; the dream of a return to the community, to a country that has been rebuilt in order to be destroyed again today. And again, as in the film, exile is at the centre of our lives. The last part of the film also tells the fantasy of a return at a time when the majority of people of all generations are leaving the country. It’s true that Maia does not find her home, nor the graves of her brother and father, nor the Beirut she once knew. But in a small country, some reunions are possible, like the one with her friends of yesterday, with her great love Raja, their ties are renewed despite the lost youth. Maia finds again loved faces, an energy, just for one evening, just one… Like a parenthesis. When Maia returns to Beirut, there’s a confrontation between fantasy, imagination, memories and the present. This confrontation opens a new relation to a past history, yet without resolving it. The past is evasive, slipping away. However, there was a transmission and a form of reconciliation. There was the possibility to relieve some of the grief, and to become receptive to the joy of being reunited. The film also relates a return to the present once the past has been evoked, unearthed, and brought out of its latency. It is a political and vital choice to be able to not end a film from the region in a dramatic way even if the tragic violence and chaos eventually catch up with us. In the profound distress that is ours, we can’t give in to absolute despair, as we so desperately need light. Indeed, There will be light promises a song at the end of the film…”