The Book of Queens, a novel by Joumana Haddad

Interlink (2022)

ISBN 9781623718473

…turn those white tents inside out like pockets, shake them, and the blackness will fall out. You see the mud in the trails and in the arteries. The threads where people’s exhausted laundry hangs like life residues.

Laila Halaby

“Freedom is a ridiculous impossibility,” ruminates Qayah in Part One of Joumana Haddad’s novel, The Book of Queens. “Just like choice. We are born in a cage we haven’t picked, at a time we had no say in deciding, in a place we previously knew nothing about, having features we did not shape, and ethnicities and religions and character traits we did not choose.”

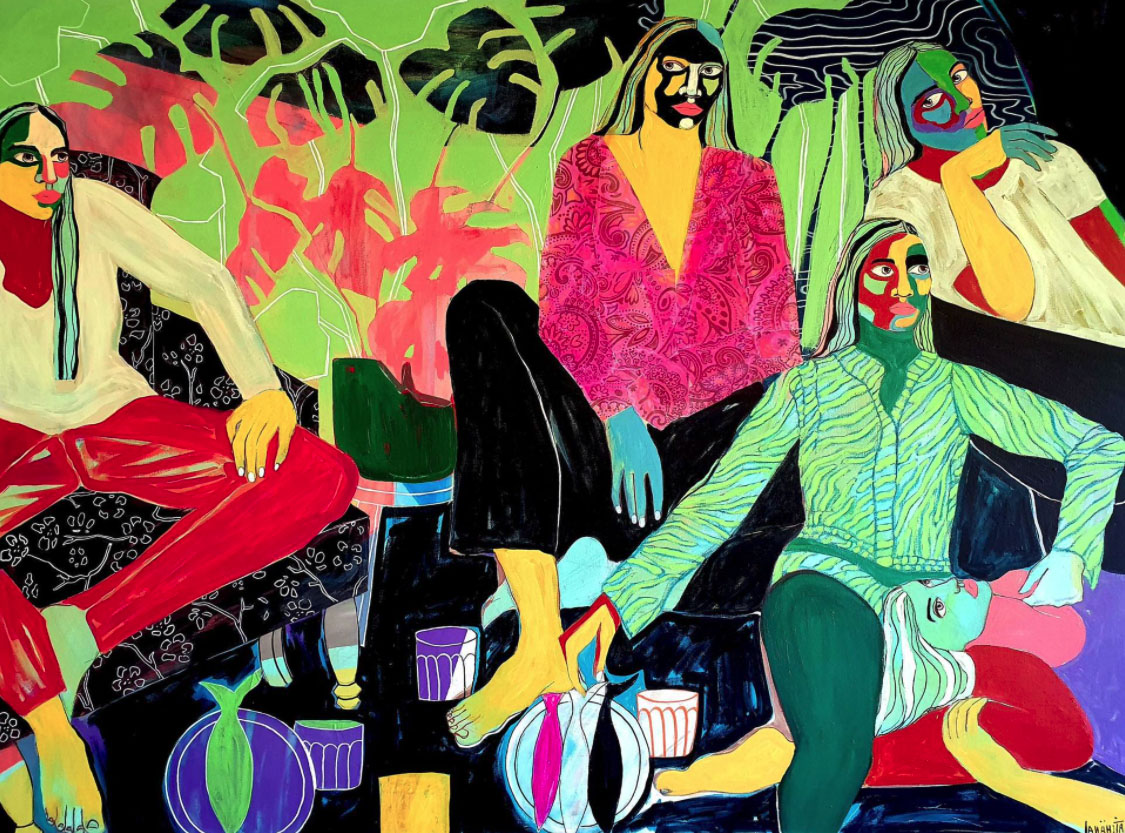

This outlook sets the tone for the unfolding of the lives of four generations of curious-girls-turned-suffering-queen in a family saga that covers a lot of territory, “a perfect circle of fire, with a circumference of one hundred years.”

The Book of Queens is divided into four sections and alternates between recounting and narrating the individual stories of Qayah, Qadar, Qamar, and Qana, each inextricably part of a larger family story that is inextricably part of so many Middle Eastern stories, including the Armenian Genocide, the occupation of Palestine, wars in Lebanon and Syria, and the inevitable refugee camps, all with religious dissonance sprinkled on top. Queens reads like a microhistory, individual voices making up a global tale of womanhood: that which is endured under the thumb of the patriarchy and that which is passed down from one generation to the next, despite fervent attempts at avoiding doing that very thing.

Does change come in breaking with religious, cultural, or linguistic expectations? If Queens is any indication, then it does… and it doesn’t. Sorrow — “no bond is stronger” — runs through all the stories like blood and red hair and “[W]ars, inside and outside, [that] would keep on tying them together endlessly, growing and snaking around them, between them, under their feet, above their heads, and around their necks like wild plants in the Amazon Forest.”

To get more of the flavor of Haddad’s prose, here is a passage from The Book of Queens:

If one looks at a Syrian refugee camp from above, they discover a sea of white tents exuding optimism and safety. Everything seems organized and neat. A haven where people flock to be saved, to be provided for and taken care of. Not exactly a dreamland, but close enough in such difficult circumstances. One must assess a given context relatively: Gaziantep versus Aleppo, not Gaziantep versus Stockholm.

But turn those white tents inside out like pockets, shake them, and the blackness will fall out. You see the mud in the trails and in the arteries. The threads where people’s exhausted laundry hangs like life residues. The tear stains on the used pillows. The improvised schools where a one-eyed orphan is supposed to learn how to count to ten. The timeworn cooktops where women take turns brewing something they need to believe tastes like coffee, or hope. The cold. The unbearable cold in winter. And then the heat. The intolerable summer heat.

Turn the refugees’ faces inside out, too. Those faces, especially. You see the shame, the desperation. The disgust. You can’t possibly miss the “I wish I had died instead” or “I wish I’d never been born at all” expressions. A forsaken limbo where the only tool of survival is in thinking, “It could have been much worse,” comparing their situation to that of those who’ve been less fortunate. Luckily, in a refugee camp, one always manages to find the less fortunate. Even if you’ve lost two kids and an arm, there will be someone around who’s lost all of their family and both legs. You just need to look close enough, to be a good disaster hunter. For the tragedy of others is your sole consolation.

Despite the heaviness and tragedy that works its way into almost all the characters’ lives, there is a lightness in the telling — even the most unjust or brutal of deaths is reported as a matter-of-fact event, the latest casualty to whom we must bid adieu — in a tone that harkens to Elif Shafak, a bemused voice noting that life is fickle and unfair, and what of it? We must go on. Besides, life is also hilarious and gorgeous.

Amid the global catastrophes are delightful intimate moments. One of my favorite scenarios involves the importance of a shoe cupboard, a father seeing all the stories lived in those “filthy items,” the “…roads taken, and others untaken, so many nice and bad encounters.” And his child, wishing she were a shoe, to not be burdened with the emotionality of humans, “peaceful, discreet, and low-profile.”

Queens is, after all, a book about families, an exploration of relationships, as well as a treatise on the personal becoming public (both in the action of the novel and in the occasion of the novel being written) especially as it pertains to women and the weight of expectation placed on them. On us. And grief. So much grief.

Joumana Haddad is a multilingual journalist, poet, translator, and human rights activist — none of which will surprise you as you read about these four women and feel her in the mix, rooting for all of them as well as mourning their losses. What a pleasure to spend time in Haddad’s company, to be encased in her ease with language, her delight at word play, and her empathy for her rich and unique characters.