Layla AlAmmar examines the Arab melancholy at the heart of Saleem Haddad’s second novel.

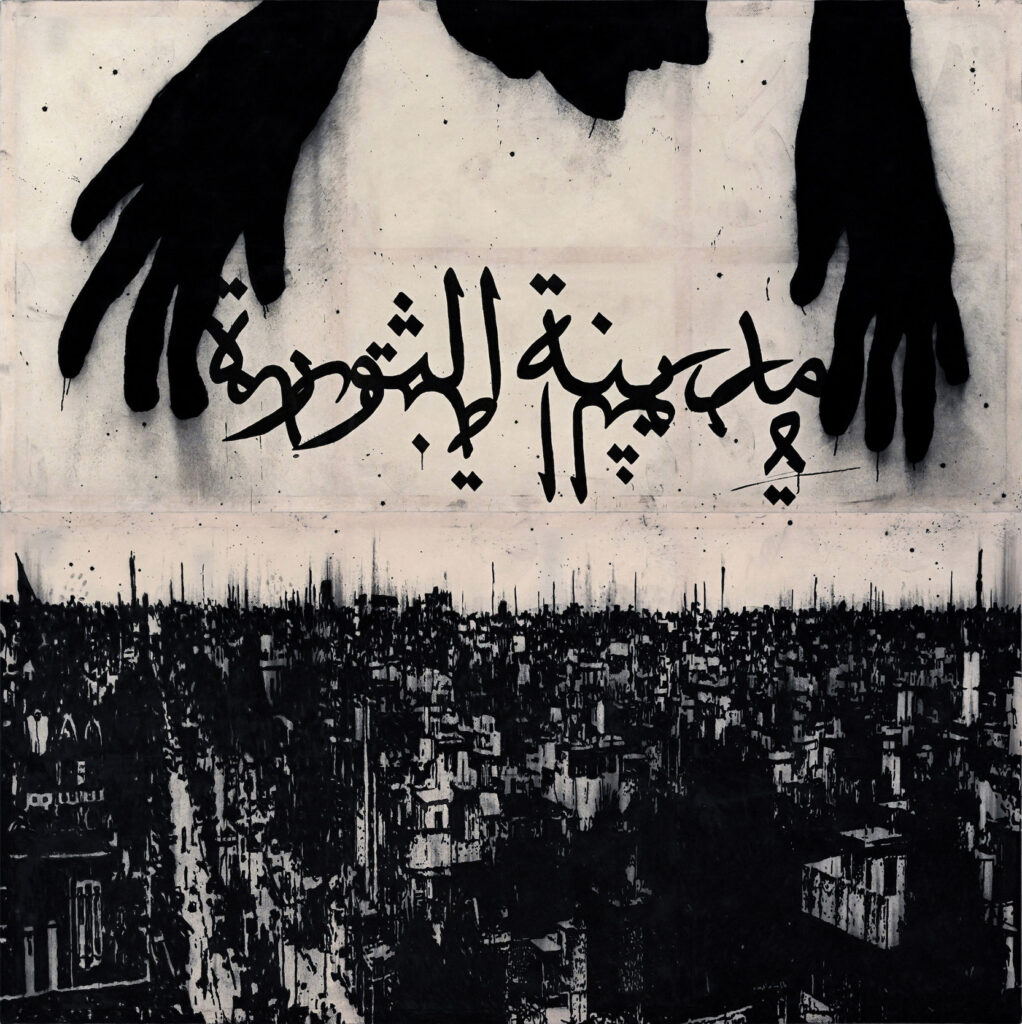

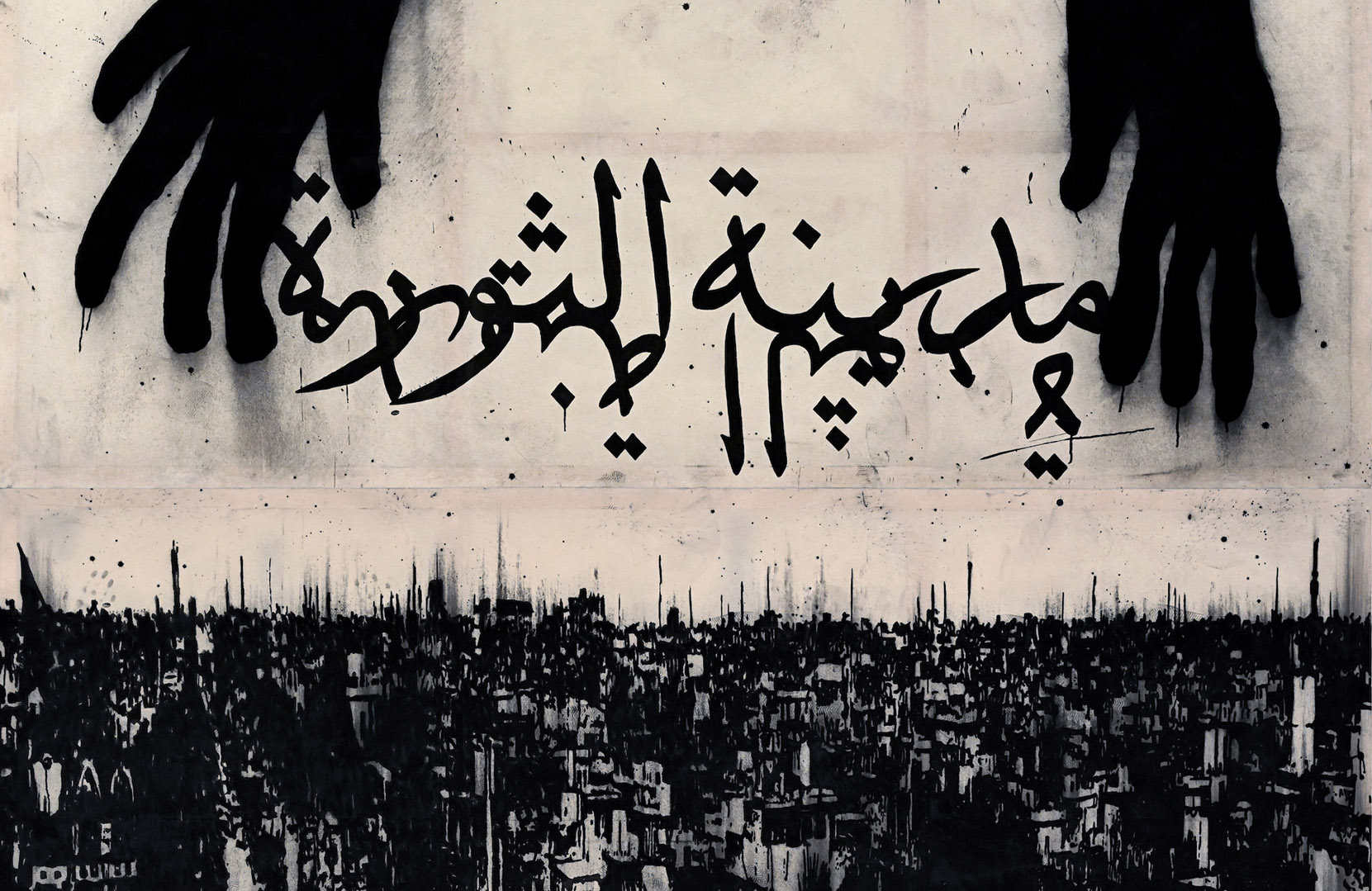

In 1980, the great Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani wrote a poem lamenting the state of the Arabs. In it, he writes of defeats, oppression, failures, and disillusionment. He writes of ruins and desolation, of talking heads and traitors. This was a time of congealing tyranny across the Arab world, of detainments and forced disappearance, a time of massacres and the brutal suppression of uprisings. It was five years into the Lebanese Civil War, and a year following the betrayal of the 1979 treaty between Egypt and Israel. On the horizon was the Iraq-Iran war, and the massacres both at Sabra and Shatila and in Hama. Qabbani’s condemnation stretches from Damascus to the Gulf and across North Africa. Halfway through the poem he admits, “I have grown weary of my Arabness… Is being Arab a curse and a punishment?”

أنا يا صديقة متعب بعروبتي…. فهل العروبة لعنة وعقاب ؟

It’s a question many of us have asked over the years. In fact, nearly three years ago I was invited to discuss the particular knot of trauma, memory, and identity that bedevils the Arab psyche. The unending catastrophes we face in this region that we call home; the way one trauma and injustice bleeds into the next; the way they are political as well as painfully personal… The genocide in Sudan; the hypocrisies of our Arab states; the ease with which horrors flow past our eyes every hour and every day — all of this is frequently more than we can bear. And the last two years of genocide in Gaza — where entire families have been wiped off the civil register, and well over 70,000 have been killed by an Israeli war machine that continues to act with utter impunity — has pushed us all over the edge. Our collective Arabness, our ‘urubah, is the root of our melancholy, the feeling that when a catastrophe befalls the Palestinian people, or the Lebanese, Iraqi, or Egyptian, it befalls us all.

Arab melancholy is a curious affliction, a strange alchemy of despair, rage, and frustrated anguish. A qahar that is always smoldering in our breast. Sometimes it rises, a cancerous qhussa lodging in our throat. Sometimes it drops into the belly, a molten and roiling heat. Sometimes it explodes from us, in shouts and protests, in raised fists, sometimes in bullets and violence. Melancholy is the persistence of love, the insistence of love, beyond all reason and hope. In the same poem, Qabbani vows that he will not repent of this love that torments him — ما تُبْتُ عن عِشقي — and that those who do so are weak and unworthy.

•

Floodlines, the second novel by the Iraqi-Palestinian writer and filmmaker Saleem Haddad, is an elegant articulation of precisely this melancholy that plagues the Arabs. The narrative moves fluidly across time and space — from London to Iraq, Dubai to Edinburgh, Kuwait, Yemen, and Cairo — as it grapples with displacement, the ravages of imperialism, and the apathy of an uncaring world. We follow multiple generations of a hybrid family of artists: three sisters, Zainab, Mediha, and Ishtar; their British mother, Bridget, and deceased Iraqi father, Haydar; as well as Zainab’s son, Nizar. Set mainly against the backdrop of 2014 Iraq (a time of extraordinary violence amidst the rise of ISIS), the novel chronicles the family’s dysfunction and fragmentation, exploring questions of trauma, grief, betrayal, and acceptance.

The three sisters, estranged at the beginning of the novel, come together upon the discovery of some long-lost paintings by their father, a famous artist. Thus begins a dispute over the paintings, and, in a larger sense, over the legacy their father has left behind. But memory, history, and myth are hard to disentangle from one another. Where does one begin and the other end? What accounts are “true” and which have been falsified? What has been buried, manipulated, or constructed? And to what purpose? There are multiple layers of betrayal which must be reconciled. The personal ones — secrets of abuse, deception, and complicity that have splintered the family — as well as the larger, collective, political betrayals of a nation fractured under the stresses of neocolonialism and the consequences of the 2003 US invasion.

Art will not save us. It will not magically make things right. But art can make us feel just a little bit better, just a little less alone.

The novel is propelled by the torments of Arab modernity, which are in turn driven primarily by constant friction and encounters with the West. These produce an array of responses, which Haddad has isolated and embodied in each of the three sisters. Ishtar, the eldest, is uncompromisingly anti-imperial, faulting Western interference for every ill in the Arab world. Mediha, the youngest, vilifies Iraq. She conceives of the country itself as a monster, channeling this perspective into the art she exhibits in Edinburgh — art that the middle sister, Zainab, characterizes as “the same tired Western bullshit, shockingly vulgar and terribly predictable.” One artwork features text messages between ISIS and British youth they groomed as recruits; in another, a knife-wielding figure that Mediha calls “Jihadi John” haunts their childhood photographs; a third is a photo of the three sisters in a paddle boat, but Mediha had superimposed niqabs and abayas on them. Mediha’s art, with its reductive, simplistic, and profoundly unnuanced representations of Islam and Iraq, is the type that might be praised for its “courage” by a curator in the West while earning nothing but scoffs from the people for whom it purports to speak. Zainab is the only one of the sisters to have remained in the Arab world, which is perhaps why she copes by maintaining a sanitized image of her homeland and repressing the most painful memories of her childhood. But her marriage to a rich Emirati and life in Dubai nevertheless makes her an imperial bootlicker in the eyes of her sister Ishtar.

In holding such rigid positions, the sisters occasionally come across as portraits of the three broadest categories that modern-day Arabs fall into: the fire-breathing anti-imperialist; the self-orientalizing Arab; and the pragmatic (even apathetic) assimilator. Ishtar, in particular, has a tendency towards intellectualization and a self-reflexive awareness that flattens her character at times.

But the novel moves beyond these archetypes in the character of Nizar, Zainab’s son. A correspondent haunted by his time in war zones across the region, we meet him at a moment of personal grief as he mourns the end of a long-term relationship with his partner, Alfie. Fundamentally unable to relate to the pain Nizar feels in the face of mass death and escalating violence in Yemen, Syria, Egypt, Libya, and Palestine, Alfie’s ability to carry on with his day, his incapacity to see how these events relate to his own life and circumstances, ultimately spells the end of the relationship. And Nizar, with his air of quiet anguish and tired resignation, is the character who most embodies our Arab melancholic condition. Like him, so many of us have had to contend with well-meaning colleagues, friends, and lovers who hum and tut and shake their heads when we talk of the latest horror. They listen, but at some point their gaze slides away — to check their phone, glance at their watch, or look out the window — little cues that it’s time to change the subject. Our pain makes them uncomfortable. They don’t understand it. And like us, they don’t know what to do with it.

The novel ends on a high note, a good decade before the current moment. In light of all that has happened since, it’s a brave choice. And one earned by repudiating that Whiggish view of humanity that has us all on an ascending escalator of progress, where violence is declining and morality, empathy, and justice are on an upward trajectory. Floodlines refuses to traffic in such a view of history, which is utterly divorced from any meaningful reality. Instead, the novel acknowledges the precarity in which we’re mired, the chaos and impotence we feel, the sense that, as Nizar says, “We are all doomed.” But within this terrible uncertainty, Haddad locates space for a radical kind of hope.

Following the signing of the Oslo Accords, Edward Said, in his essay “On Lost Causes,” circles the notion of our Arab melancholy and the curious hope that finds fertile ground within it. Rightly seeing Oslo as a surrendering of the Palestinian struggle for liberation, he writes, “Does the consciousness or even the actuality of a lost cause entail [a] sense of defeat and resignation? … Must it always result in the broken will and demoralized pessimism of the defeated?” He answers in the negative, insisting that there is another road one might choose in the face of seemingly endless catastrophe. For him, the alternative lies in:

the intransigence of the individual thinker whose power of expression is a power — however modest and circumscribed in its capacity for action or victory — that enacts a moment of vitality, a gesture of defiance, a statement of hope whose “unhappiness” and meager survival are better than silence…

Said believed that we can only move forward by holding fast to an “unabated conviction in the need to begin again, with no guarantees.” And this is the radical hope that Floodlines ends on, in the form of an uneasy and imperfect reconciliation between the three sisters. Coming together in Iraq to lay their father to rest, the family’s bonds prove more resilient than the radical differences between its members. As I suspect Qabbani realized, there is perhaps no transcending the “curse and punishment” of our Arabness. But the flip side of that curse is the huge community it gives us; the larger Arab family, nearly half a billion people who share the same grief across time and space, even if they choose to deal with it or represent it differently.

It bears mention that in Floodlines, it is art that ultimately binds the family, for better or for worse. Art is also what binds us to ourselves, especially in these times of profound Arab grief. In the face of the precarious and unpredictable, when we feel defeated and weak, human beings maintain an extraordinary capacity for expression. We write, we paint, we sculpt, we sing, we dance. We yearn for what is beautiful and good. We create. And in that creation, there is life and a spirit of resistance that goes beyond mere survival.

Art will not save us. It will not magically make things right. But art can make us feel just a little bit better, just a little less alone.

And sometimes “just a little bit” is enough.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)