Introduction to the Markaz Review’s Love, Sex and Desire issue

Looking back nearly a year ago, there is a kind of innocence in “From the Middle East, with Love,” in the article’s expressions of affection in Arabic, Persian, Hebrew, Turkish and Kurdish. The hopeful emotions embedded in those languages suggested all of us could somehow make our way forward through mutual love and respect. In the last five months, since October 7, that glow has been darkened by the war in Gaza, and my thoughts for The Markaz Review’s February issue on Love, Sex and Desire (LSD) turn to the interactive website, Queering the Map.

Pin-pointed to geo-locations on a Google world map, in some 28 languages, members of the LBGTQIA community have left anonymous heartfelt expressions of hope, dreams, and encounters. Honest and oftentimes heart-breaking, Queering the Map is a digitized archive of loves, lost and found, for troubled times.

Some of the messages of love’s labors in traditional homophobic and transphobic societies have been made even more impossible by war. Under the banner: “Free Palestine Now,” someone wrote:

I’ve always imagined you and me sitting out in the sun, hand and hand, free at last. We spoke of all the places we would go if we could. Yet you are gone now. If I had known that bombs raining down on us would take you from me, I would have gladly told the world how I adored you more than anything. I’m sorry I was a coward.

It’s a heavy burden to bear when the thinnest barrier exists between the political and private.

I wish I could watch the sunset over the Gaza sea with you. For one night I wish this occupation was no longer and that we could be free for once on our own land.

Queering the Map is also filled with unexpected epiphanies:

First time visiting Israel/Palestine, I dated an ex-air force officer after we matched on Tinder. He was trying to impress me by telling me he targeted a residential building in Gaza. I’ll never forget this date, it changed my whole perspective about the conflict.

Ignoring some of the warnings on the website comes at its own peril:

I received messages at Grindr from Israeli men wearing military uniforms saying they will kill me with photos of D9-Z machine guns with laughing faces just a few hours after I landed at the airport. I had to delete the Palestinian flag next to my name to stop receiving these kinds of messages. This was my first time visiting the land my grandparents were kicked out of, using the privilege of having a Canadian passport.

Love — or rather the lack of it — reveals deeper meanings we knew and recognized, but for whatever reasons we couldn’t immediately acknowledge:

Every now and then I open on this website to re-read the Palestinian stories, and every time I cry. I wish I was able to share an lgbtq experience I had in Tiberias but I can’t because I’m a refugee. The only thing I know about this place is what my grandparents went through in … 1948. Not love but misery. To anyone reading this, please don’t support settler colonialism. Please don’t support our ethnic cleansing.

Borders have blighted both queer and heterosexual lives. It is fitting for the Love Sex and Desire issue that Markaz’s senior editor Lina Mounzer reviews Love Across Borders: Passports, Papers and Romance in a Divided World, by Anna Lekas Miller. Mounzer sent me a voice note about her initial impressions of the book. “Borders mediate our families and lives and the most personal things about us. It is also a history of how borders and passports came about, their politicization and the migrant crisis. A book with a lot of tenderness.”

Mounzer was also the editor of the prose poem, “Don’t Ask Me to Reveal My Lover’s Name,” by the Egyptian filmmaker, now living in Berlin, Mohammad Shawky Hassan. In it, the filmmaker questions, as she explains, “the ephemeral nature of desire and at the same time the ephemeral process of how actual ideas and memories get turned into film.” A letter of sorts, it was written to someone he made a film about, who has since died. “And we don’t understand Mohammad Shawky Hassan’s relationship,” concludes Mounzer, “because he’s trying to understand it.”

Love always leaves us wondering.

For some women, many of their first “brushes” with — one can’t call it love — other peoples’ sexual desires take place when these women are far too young. Aspects of Joumana Haddad’s memoir piece, “Porn, Sade, and the Next-door Flasher” are disturbing. Her formative encounters, admits the Lebanese writer, have had long lasting consequences in this brutally honest, at times darkly humorous essay; as a young girl she initially picked up Marquis du Sade because she mistook it for young adult/children’s literature. The reason she feels she has to speak out now is in part to address the lack of sex education across the Arab world. But she has a more pressing goal. That is: to lay waste to an idea prevalent across the region that a woman’s body belongs to her family or to her husband — never to herself.

Naima Morelli, in her review of the art exhibition, I Can No Longer Produce the Limits of My Own Body, at Nika Projects Space in Dubai, further explores this idea. Morelli quotes Shireen El Feki about “the spectrum of the forbidden” across the Middle East and how the control of women’s bodies and sexuality is linked to reproduction.

Featuring women artists, mainly from the Middle East, the exhibition is, according to its curator Nadine Khalil, “women-centric” but not focused on “the gendered body.” Interesting the curator’s own awakening concerning art and the female body came in a visceral reaction she had to Mona Hatoum’s 2004 exhibition Here Is Elsewhere, the artist’s choice of women’s artwork from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The artworks Khalil brought together in I Can No Longer Produce “interrogate the notion of boundaries … occupying space …”

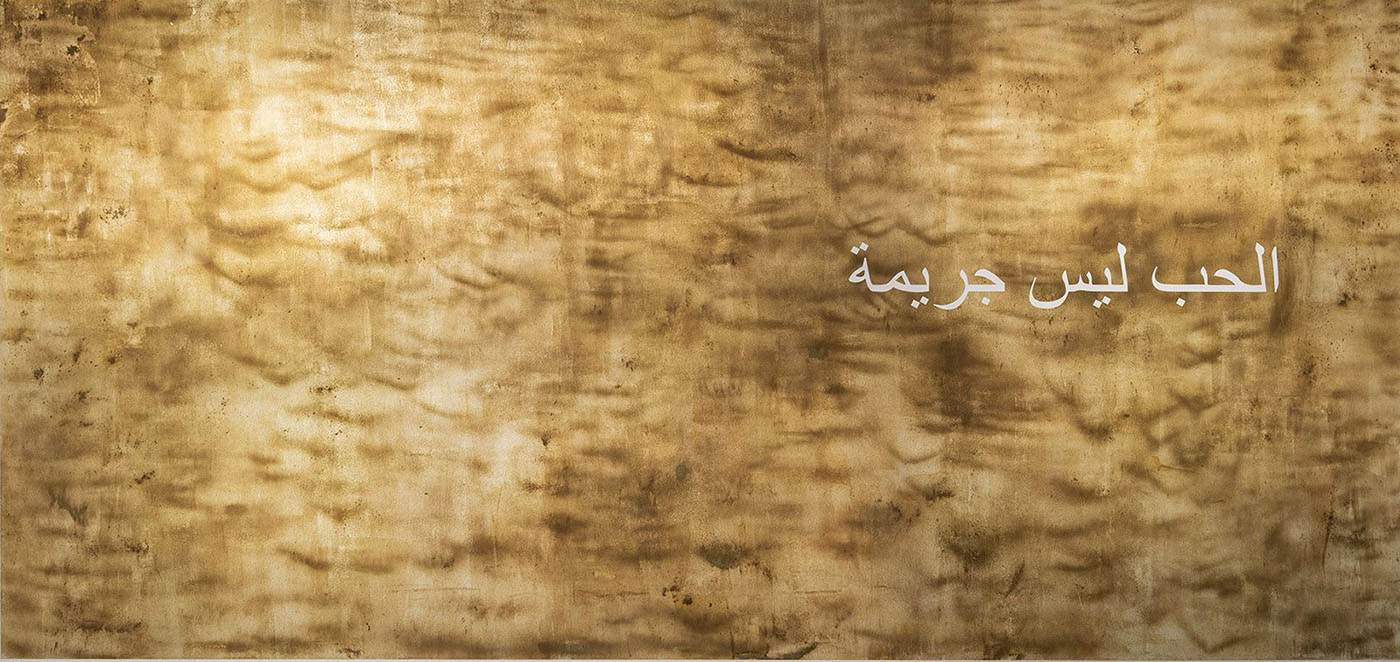

Bodies, land and bedrooms can be occupied. The featured artist for LSD, the Palestinian artist Rana Samara (b. 1985, Jerusalem) is a graduate of the International Academy of Art Palestine, Ramallah. I had written about her in my article on the creative resistance in Palestinian art. She is one of the young artists cited by Zawyeh Gallery’s Ziad Anani to watch out for. For Intimate Space, her first solo exhibition, in 2017, at Zawyeh, Ramallah, she interviewed women in al-Amari Refugee Camp about virginity, sexual desire, relationship and roles.

In an interview she described growing up in a typical Palestinian family. “I spent most of my childhood and teenage years observing and analyzing social and gender relations. I came to understand how precious, yet also suffocating, women’s roles as careers and nurturers can be.” Her paintings, to quote from a recent Zawyeh press release “often depicting the aftermath of sexual encounters … are remarkable visual metaphors of the lives of Palestinian women existing in restricted environments, cramped and constrained by internal traditions and external forces.”

Despite what seems at times unbending and draconian social pressures on female existence, some women do make their own decisions when it comes to their lives and bodies. In “It’s Just Blood,” by Egyptian poet now living in France Alaa Hasanin, the tone of the female protagonist speaking in this translation from the Arabic by Salma Moustafa Khalil is blunt and challenging:

The next morning / I swallowed a smuggled pill on the metro / And thought: He’ll die on the street / He’ll be a dead child, a beautiful child.

Her decision may not have been about sex, love, and desire but it stems from the ramifications of sex, love, and desire. Hasanin’s other poems rarely celebrate the onset of love but rather mourn the aftermath of its loss.

Another fiction writer The Markaz Review has championed is Farah Ahamed, a human rights lawyer born in Nairobi. Her short story “Drinking Tea at Lahore Chai Masters” is a tale of woeful romance between two women. The main thrust of the story could have been about love that dares not speak its name in most Islamic cultures, repelled by same-sex love. Instead it manages to be nuanced and circuitous about the nature of both romance and storytelling.

For many of us, the true meaning of love is encountered for the first time within the family. Another telling message from Queering the Map comes from Afghanistan this time:

I came out to my parents as Agender over text. Almost a year later, they are slowly beginning to understand. My dad sends me photos of news articles he sees about they/them pronouns.

Even love within the family can be complicated but not impossible.

For this issue, the Arab Iranian writer Maryam Haidari recalls a sister’s love beyond the call of duty in a health crisis. Her piece, entitled, “A Treatise on Love,” was translated from the Persian into English by Salar Abdoh.

Since high school in Ohio where I grew up, the invisibility of the Middle Eastern family in world literature has always mystified me, and I remember discussing this void with Raja Shehadeh. MK Harb is a writer whose humorous, pointed stories about Lebanese family life seem affectionately real to me. After reading “Double Apple” for LSD, I emailed him and asked him about fictionalized family memoir. He wrote back, “I think being born the year the war ended and the youngest — my siblings are 20 years older than me — made me surrounded by fascinating adults at an early age because there was no one else my age. So I try to be faithful to these neighbors, family and friends and their undiluted worldview.”

“Double Apple” turns on a cousin’s request, his cousin’s response and an ensuing adventure, in a Beirut from a very specific time.

It is through Salar Abdoh’s fiction that I find myself thinking about the lives of paramilitary men I normally feel estranged from, because of their destructive role in the ill-fated Syrian war. His short story for LSD, “Water,” brings together unlikely protagonists. One is a man who served in a Shi’a militia. Another is an English literature professor and a third “character” is Melville’s 19th century classic Moby Dick. After I read “Water” I wrote to Abdoh and asked him why he’s so insistent on writing short stories about these kinds of men; and how he manages to make someone like me care so much about them. His answer by email:

“I write about such men because so many of them are so misunderstood, or perhaps more precisely not understood at all. Men who can commit terrible things, but there is a kernel in them that is pure and just never had a chance to bloom, mainly because of circumstance. No one writes about them, and if they do it is from a viewpoint of condescension or dislike or downright aversion. Somebody had to take up their voice, as complicated and even ugly as that voice can be sometimes. And I did it, well, because I’ve been to places with such men that others have not, and I know something about brotherhood.”

There’s love of country, culture and religion in “Water” but after such extreme experience, perhaps that’s not enough. The story details the main character’s alienation and his tortured journey back to wider society, and eventually redemption. Abdoh’s fiction and his translations of other Persian writers have greatly added to the wealth of literature we feature in The Markaz Review.

It would be spurious to suggest that all emotion is heartfelt. A case in point is the essay, “The Tears of the Patriarch,” also included in this issue. The excerpt is from feminist scholar Dina Wahba’s groundbreaking study, Counter Revolutionary Egypt: From the Midan to the Neighborhood, published in the Routledge series, Studies in Middle Eastern Democratization and Government. In it, Wahba unpicks Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s use of crying in public to engender loyalty among his followers and the wider Egyptian public.

However, for some Arabs, love and life loom greater than politics. The Markaz’s Arabic editor and Egyptian novelist Mohammad Rabie has written about the popular podcast for the region, Bath ya Hashem hosted and produced by Sara Eldayekh and Hashem. The podcast’s title is a play on words since ‘th’ in bath — a difficult sound in Egyptian dialect — comes out as bas, which means broadcast or stop. Each show has a theme. Leading the conversation on relationships, jealousy, desire or even why “good boys” don’t end up in relationships is Sara Eldayekh, originally from Lebanon, now in Berlin. These topics are usually illustrated by popular song. Hashem, a music producer, illustrator, designer and photographer originally from Cairo, now lives and broadcasts from Amman. Markaz editor Rabie includes links for the podcast in his article, which was translated from the Arabic by our managing editor Rana Asfour.

Dear Readers, consider this introduction to our February issue an extended Valentine in which I’ve lingered. For the last couple of months, the editor of The Markaz Review Jordan Elgrably and I have been coediting Sumud: A New Palestinian Reader for Seven Stories Press, in New York, due for publication in October. The constant reading and worry for Palestine during this time of war has made musing on love a small oasis for me.

I’m about to end with a young Palestinian poet whose debut collection of poems, Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow. (Haymarket Press, 2022), has been on my desk this past week. Its author Noor Hindi comes from my neck of the woods — northeastern Ohio, which unbeknownst to the rest of the world is a hotbed of immigrant Arab-American family life and culture. Perhaps the “yellow” referred to in the collection’s title addresses not just “real” enemies but the stupid, racist, xenophobic attitudes surrounding the fight for social justice for Palestine. Hindi’s experiences, sense of moral outrage and love of family inform her sharp, modern writing, which includes the iconic poem: “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying.”

I was struck by her dedication at the front of her book: “For those on the outside of the door. Let this book be an invitation, as prayer, as love, come in.”

Perhaps in a broader sense, love of humankind is about acknowledging vulnerability, and that sometimes means leaving a space in your heart for your adversaries. But then like all destructive love affairs that have ended in unacceptable violence, more often than not it’s best to shut the door firmly and turn the key in the lock.

—Malu Halasa, Literary Editor

Endnote:

The title of this essay comes from the song “Poison Arrow” by the band ABC, which reached No. 6 on the UK singles chart and entered Billboard’s Hot 100, at 25, in 1982.