Love is more than sex and desire, it is a boundless force and a bond between two people in a relationship. In this account, the writer realizes how love changed her life forever.

Maryam Haidari

Translated from Persian by Salar Abdoh

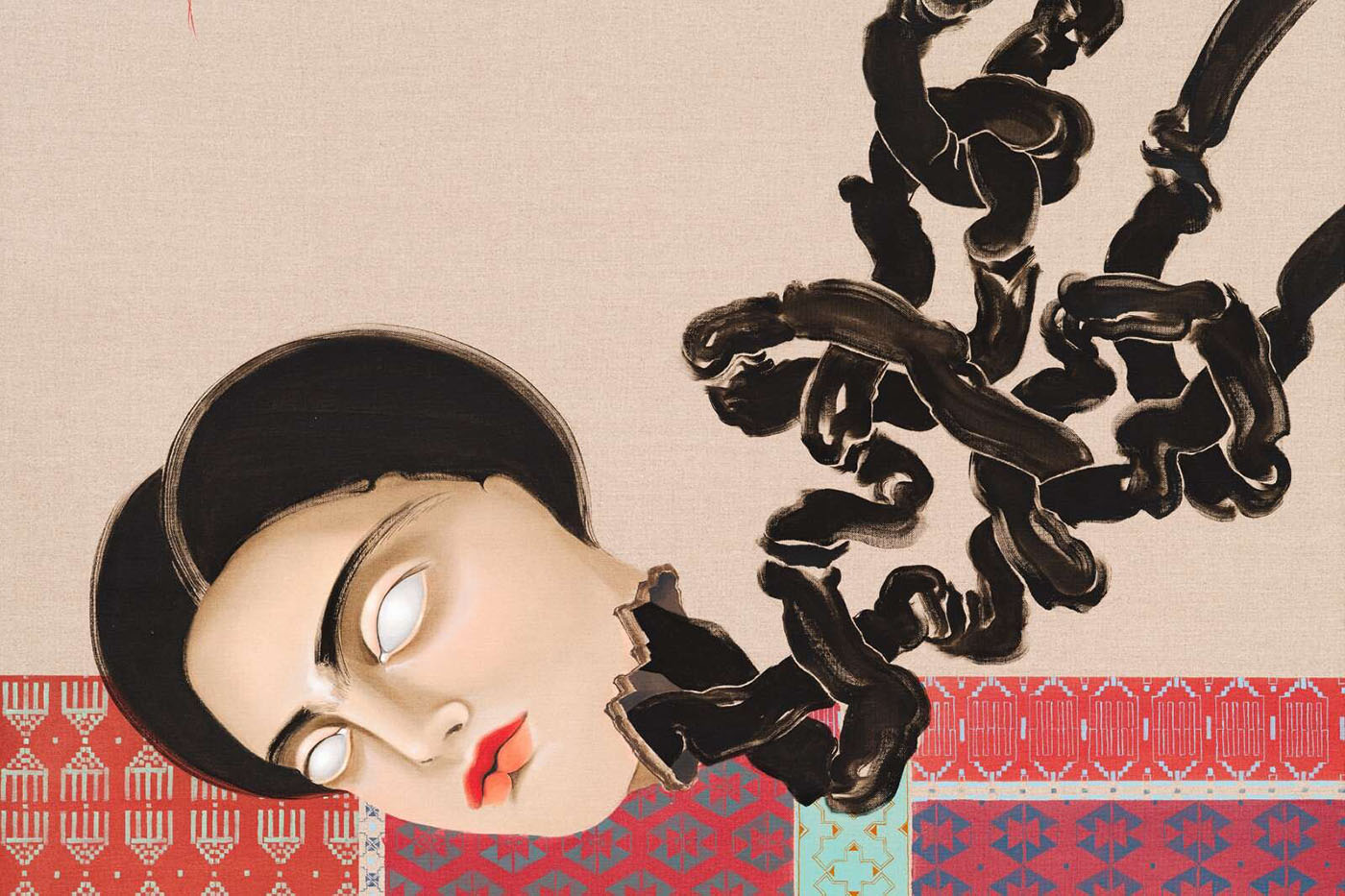

I listened. Motionless. Lying on a hospital bed in Tehran. Only a day had passed since I had finally opened my eyes. The nurses kept letting me know where I was, what I was doing there and what had happened to me. And now a friend sat at my side reading from one of Shihab al-Din Suhrawardi’s Persian works:

Love spoke, “I come from beauty’s gate. My house sits adjacent to sorrow. And my occupation is travel.”

“Do you need anything from your apartment?” my sister, Khadija, had asked.

“Bring Suhrawardi’s Treatise on Love.”

The friend continued to read: I am a Sufi alone. Going where I go. Residing where I will.

Though they had already told me countless times what had happened to me between Tunis and Tehran, everything remained a blur. Day and night were indistinguishable. The hospital lights bothered my eyes. I’d heard one of the nurses ask another, “Has she any idea what has happened?” The other nurse replying, “Yes, I told her.”

What I knew was I hadn’t been in an accident or fallen from anywhere. And this hospital was not in Tunis and that it was Persian I was hearing, not Arabic, and — most importantly — I wasn’t dead. Nor was I dreaming. These things I knew. And I was certain that it was indeed Suhrawardi’s words I was hearing just then from eight hundred years earlier: If I were to tell you of my realm and describe the marvels therein, you would be perplexed and unable to understand.

Meanwhile, around me people kept repeating the same sentence: “We thought we had two deaths on our hands, Maryam and her sister Khadija.”

Khadija said little except to bring me things — the treatise at first, then my favorite lotion which she held to my nose so I could take in its scent before she applied it to my face and hands. She told me that our mother had visited from Ahwaz and that I needed to sip my protein drink.

They had rushed me to the hospital after I passed out. Apparently one of the doctors had taken one glance and pronounced, “There’s no hope for her.” Hearing the doctor’s words, Khadija too had dropped to the hospital floor.

Two deaths, they’d imagined. But now both of us were alive.

The medical team had given me no more than a one-week window. One week to find a liver that matched my blood type. In a coma, I knew nothing about any of these things. On the fifth day a liver was matched. A few hours later the transplant was done. And now I was alive.

I could barely open my lips to speak or move my legs. My right hand was completely immobile. The world was still a haze through my eyes. But I could hear everything being said around me clearly. At some point another friend had whispered, “Just imagine, a few days ago the doctors handed your liver inside a jar to Khadija.”

Seven years have passed since those words were spoken to me. And barely a day passes that I don’t think about the image those words describe. I am still alive; my hands function, my eyes see. But everything that is me is suspended forever between the day my sister carried my dead liver away in a jar and the life I had lived until that time.

Astonishment, love, tenderness, grief, tears and helplessness — which of these was my sister feeling as she carried a bloody part of me to the pathology lab at the hospital? This same sister who could barely stand the sight of a surface wound during our childhood. What distance did she carry that vessel in that building? I ask myself. How many meters? How many turns from one room and one floor to the next?

Had an ordeal such as this not been a part of my life, maybe today I could recall many things, including the experience that they call love, with a nostalgic bent, so that I could give into the dictates of sentimentality and of past lovers that I once knew and lost. But the image of my sister carrying that jar — her emotions a mixed bag and a tempest that spelled hope, determination and vulnerability — lends every memory I possess a dimension beyond itself. Love that day was the hands of a woman wrapped firmly around a receptacle inside which lay the stilled liver of her sister.

Khadija never spoke of any of this to me. Not then, not afterwards. Others did.

Our mother, on the other hand, is different. She talks. A woman from the provinces who speaks her mind. During those days of coma when she came up to visit me from Ahwaz, they still had not told her about the gravity of my situation. Later on, she would call me and cry over the phone. “Yumma, Yumma,” she had breathed into my ear in our native Arabic, but saw that I could not hear her at all.

There are voices that we think have not heard (a mother calling to her child teetering between death and life), or instances that we never witnessed in person (Khadija carrying a part of her sister to the pathology lab of the hospital). But because they happened, life changed forever. And because it did, so did the meaning of love.