Inaam Kachachi is scheduled to appear in two talks at the 2023 Emirates Airline Festival of Literature this February in Dubai. Her first appearance will be alongside Yasmina Khadra in which the authors tackle politics and longing. They will discuss the state of the political novel in the Arab world as it is written from the diaspora, and what it means to be an Arab today. Throughout her novel, The Dispersal, excerpted below, Kachachi toys with the central question of whether it is best for a person to remain within one’s homeland, among family and all that is familiar even if it means suffering the hardship of war and a constant fear of death? Or whether one is better off moving elsewhere, to safety and stability, despite the sustained feelings of alienation and foreigness?

Kachachi’s second panel will be shared with Tareq Imam, where the two will divulge the secrets of inciting fear in fantasy — from their explorations of electronic cemeteries, in Kachachi’s Tashari, to places made out of endless walls, in Imam’s City of Infinite Walls.

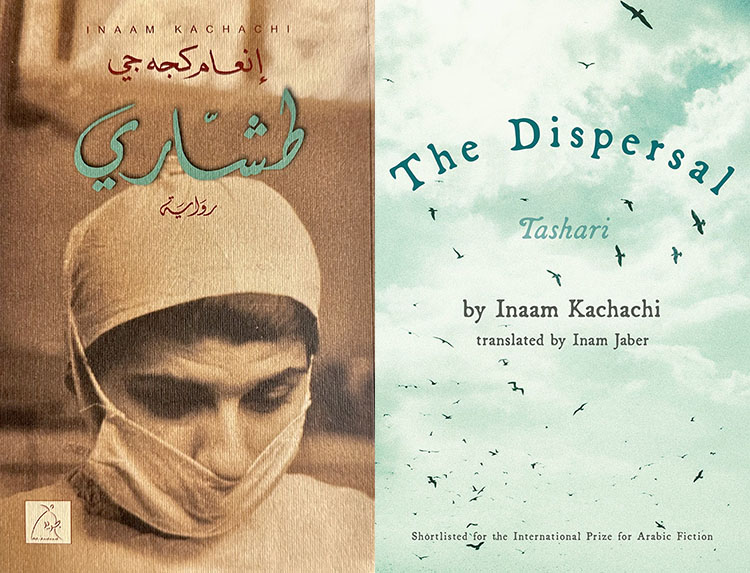

The Dispersal, or Tashari, the book’s title in Arabic is an Iraqi word for a shot from a hunting rifle, which scatters creatures in all directions. The word tashari expresses the scattering of Iraqis as a people across the globe and the separation from home and loved ones that pursues them. Within the novel, it is used to refer to the Christians of Iraq in particular who have dispersed throughout the world as a result of the country’s sectarianism.

It is a timely and insightful novel about displacement, loss, poetry, war, and migration from a leading Arab voice. Released last year in English, Kachachi’s writing has been described as a “spontaneous reflection on the closest ties of family that evokes quiet power and beauty, relayed by the warmth of Inam Jaber’s translation.”

The novel follows the career of Wardiyah Iskander, a physician working in the Iraq countryside in the 1950s. Delivering babies and tending to the many health needs of her rural women patients, she struggles to improve care for them. But as the years pass, the upheavals the country faces continue to worsen. Her family, like many others, is pressed to leave. Wardiyah finally goes, arriving in France. There her niece, a poet, helps her now elderly aunt to get settled and, reflecting on their family’s dispersal, to tell her story.

Wardiyah develops a bond with her niece’s son Iskander, who has grown up in France alienated from his extended family, his language, and his culture. As he gets to know his great-aunt, the doctor, he learns more about his people’s calamities and extraordinary heritage. He is inspired to construct a virtual graveyard online, a digital resting place where families can be reunited again.

—Rana Asfour

Excerpt from Dispersal, Chapter 25, by Inaam Kachachi.

Had it not been for that mad young woman, Wardiyah’s way of life would not have changed.

Had it not been for the nightmares, Paris wouldn’t have allured her, nor would any city in the entire world. Even missing her son and two daughters had become a simple fact that she dealt with by shedding a silent tear and taking two expired sleeping pills, imported from Jordan. She kept hoping they could be reunited in one place, one country, or even in one continent. But the nightmares overcame the day’s hopes. She was strong, wise, and experienced. But she was too weak to control her subconscious. She couldn’t program her dreams or her visions.

Wardiyah switched off the TV and closed her eyes to sleep. She had moved her bedroom. She used to have it on the second floor. But now she chose to have it in the study on the first floor, which overlooked the garden. The house wasn’t crowded, and the pain in her knees wouldn’t allow her to climb up and down.

Also, the double bed in the bedroom reminded her of Jirjis, of where he had slept and where he had taken his last breath. His hand let go from hers and he passed away. When she felt he was dying, she took the oxygen muzzle off his nose and gave him a handful of cold water; he should not die with a dry throat after six months of thirst.

In the eastern room, near the deep-rooted date palm tree and between the two olive trees she felt secure and enjoyed tranquility. She wasn’t afraid of thieves, although gangs were moving freely throughout Baghdad. She sold the Persian carpets, the silver spoons, and crystal chandeliers. She was left only with her wedding ring, the stethoscope, heaps of drugs in the drawers, and her husband’s books and magazines on the shelves of the library. She enjoyed dusting them every day and she didn’t want to discard them, as they were so dear to him; he looked to them as his treasure. But now nobody would want them. Even thieves would shun them as trivial and wouldn’t be tempted by them. Now they were capable of examining houses with mineral- detecting devices and categorizing which houses laid golden eggs and were worth visiting, and which ones hatched only cheap metals, unworthy of their visit.

Wardiyah closed her eyes and slept, and the nightmares began broadcasting in her head. She thought of calling to the Virgin Mary before sleep so that she might see her in her dreams. That was what her departed sister Julie used do every night, and Mary would be standing behind the curtain, ready to enter her dream theater.

She also yearned for her three far-away grandsons in Canada, that they might come see her in sleep. The Virgin Mary, however, was not attentive to her, and the loved ones were busy with their lives. Only the persistent nightmares found a way to her. She resolved to close the door of her mind, but dreams held the key that could unlock all the locks.

“You work out your own plans, but in the end fate laughs at them.”

That was what her brother, Sulayman, would say when confronting the vicissitudes of his life and everything related to his sons’ and daughters’ affairs. They learned the expression by heart and believed it. The youngest daughter, however, wanted to rebel against predestination. In a moment of thoughtlessness, she dared to ask him, “Dad, will you take me to London if I score eighty out of a hundred in secondary school?”

“Do you know that your grandfather, Iskander, lived sixty- seven years without setting a foot outside Mosul?”

“Our grandpa lived in an age different from ours.”

“Stop it!”

He shouted at her in a way that made the daughter swallow her tongue and not repeat what her father called disrespect. He stressed every segment of the word: dis—re—spect, which made the word linger in one’s mind and never leave. Perhaps he doubted that London was present in his daughter’s book of destiny. He might have stubbornly resisted the unknown, a blurred unknown that defied deciphering.

After a number of years, the girl married a young man studying in London. She accompanied him and pursued her studies there. Then she came back and worked as a governmental employee, but she was fired, because she belonged to no specific political party. Finally, she emigrated to a remote area.

Tashari was what her loving niece was writing. She wrote poetry about loved ones who had dispersed and could only be reunited on maps. She was a romantic poetess. She was unlike her aunt, who didn’t want her niece to slide into the trap of nostalgia. It was a psychological disease that attacked the weak and the defeated.

Wardiyah was not inclined to accept memories from “the good old days.” What was good was decided by God. That was what she had been taught since she was young, and so she went forward without turning back or protesting. The unknown had been cunning with her and pushed her to the farthest borders. She got used to its tricks and was no longer surprised by anything unexpected that might knock at the door of her old age.

The unknown had taken her outside the borders of Mosul and permitted her to study in Baghdad. It had allowed her to put on the lab coat and the white mask and had drawn her out of a conservative family to plant her in Diwaniya ,where she had lived in a different world, with a mix of dialects on her tongue. The deceitful unknown allowed her to orbit, with her groom, around cities of Europe and granted her matchless opportunity.

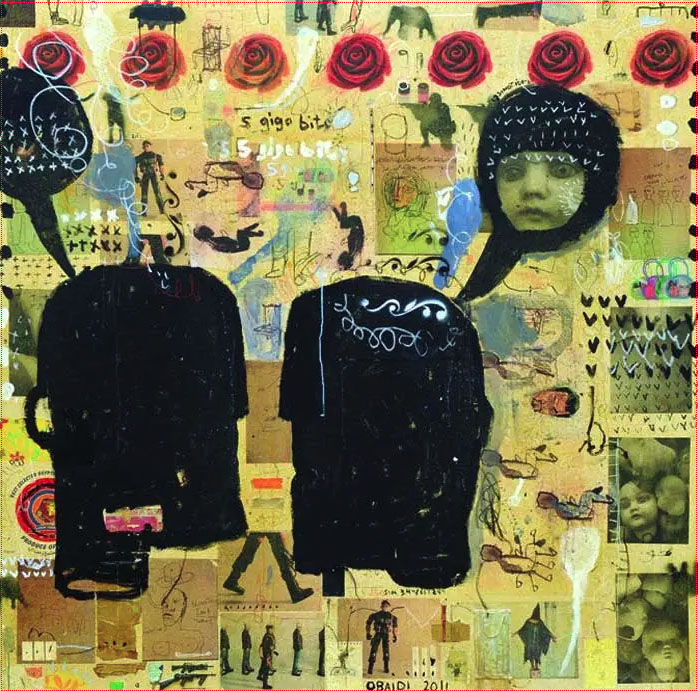

Her only leave time had been when she gave birth to her babies, and even then she would get up before her blood had dried out. She gave birth at the hospital where she worked every day. It was a building that held her work, rests, pains, and her love. It was the place where she took a deep breath and inhaled the smells of many of aba’as, be they of the women standing or the women sitting in front of her with their necks craning in her direction.

She wasn’t disturbed by the smell of the bodies, mouths, or armpits. She lifted the breasts, the saggy abdomens, and wiped the layers of skin with cotton and antiseptics. She was like the policeman who would go to work even on his holidays, since it was the only place where he felt he was of value. And had it not been for that young woman strapped with the explosive belt, who visited her in nightmares, Wardiyah wouldn’t have left work in the clinic until Azrael, the Angel of Death, came to her.

Of course, Azrael would only come suddenly to see her busy on the examination table, wearing sterilized gloves and messing with vulvas. Or he might feel shy, and decide to come late, allowing her to move to Baghdad, retire, and open another clinic. She kept up the work and forgot about herself.

Wardiyah recalled how the young woman had entered the clinic, shivering. Folding her aba’a around her body, she pushed the other women waiting aside so that she could get into the exam- ination room first. She was stopped by the housecleaner, who asked her to sit down in the waiting room until it was her turn. But she stood up angrily and said,

“Hide me…I will die.”

Wardiyah thought that the young woman might be pregnant outside of marriage. She was ready to send her out of the clinic. The patient, however, refused to leave, and her shivering grew more intense. Her eyes rolled back and she fell. The housecleaner helped her to the examination table. Her face had turned pale, and she was in a serious condition.

When Doctor Wardiyah placed the stethoscope on her chest, she felt a solid layer. She tried to remove the patient’s dress, but the woman stood up and pushed her away. Opening her eyes, she held on to the doctor’s arms. Tears were running down her face, and her lips turned bluish.

“I don’t want to die…I don’t want to kill you and die.”

Wardiyah removed the woman’s dress and saw that the woman’s chest was belted with white, brown, and green packets, rolls lined up with tape like the ammunition belts worn by soldiers. The doctor’s body stiffened and she couldn’t move away, with her patient’s two arms clutching at her as if asking her to restrain her. Four eyes met with horror culminating between them. It was the fright of the animal facing the hunter’s gun and their alertness, confronting the quarry.

The housecleaner ran away, shouting:

“An explosive belt, this woman’s a bomb!”

A short circuit cry of shock rose up from the women in the waiting room. Abandoning their aba’as, slippers, bags, and baby strollers, they pushed to get out into the street.

Wardiyah pulled herself free from the woman’s cramped fists and moved back. She bumped into a chair and fell in front of the metal table. She tried to get up, but her knees refused to help her. Wrapping her hands around her head, she waited for the sound of an explosion.

A few seconds passed as if they were ages. She prayed that it might end quickly. Half-conscious, she glimpsed an image of Jirjis on his death bed. She wanted him to protect her and gave him her hand so that he could pull her away, but her arm didn’t respond. Her vision got cloudy, and she thought the electric power was going out. Dizzy, she surrendered to the light emptiness in her head. And before she fainted, she heard the girl’s teeth chatter:

“I…d…o…n…o…t…w…a…n…t…t…o…d…i…e.”

“Thank God, Doctor. It’s over.”

Wardiyah recognized the hoarse voice of the owner of the neighboring pharmacy. Opening her eyes, she tried to move. She found herself lying on the floor between the shelves of drugs, covered by a men’s aba’a, with smelling salts near her nose. The horns of the police cars made her head ache. She glimpsed many faces crowded over her; some she knew, and others she didn’t.

Dozens of mouths were moving in praise of God, and hands spread water. Her dress got wet, but she couldn’t tell whether it was real or in a nightmare.

She saw two officers shooing the crowd away, shouting at those who were present to be quiet. The officers squatted close to her.

“Do you know her…Is she one of your patients?”

She needed someone to retrieve her chair and help her get up; she felt ashamed lying on the floor. She touched her face and tried to reach to her handbag; she thought of Yasameen and worried about how she would react to the news.

“I don’t know her… I haven’t seen her…What happened?” “She felt afraid and didn’t blow up the belt. We put her in

prison. Don’t worry.”

Death had come so close to her and passed by without asking her to accompany it, leaving her with the image of the pregnant woman with the belt bomb and the sound of her chattering teeth. She couldn’t erase from her mind the view of the scared girl with the rolled back eyes, who had reached out stiff fingers to cling to life, a young woman who had rebelled against a programmed death.

This excerpt published by special arrangement with Interlink Publishing.