The new book by Hassan Blasim explores jihad, exile, and the surreal life of the refugee through stories that defy convention.

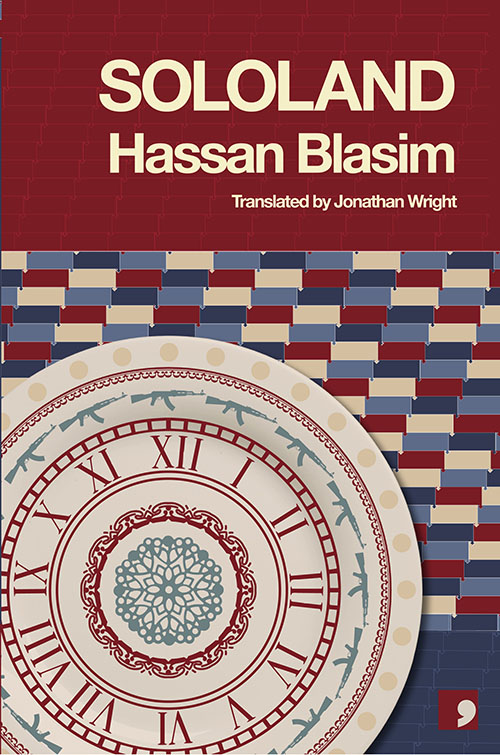

Sololand by Hassan Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright

Comma Press 2025

ISBN 9781912697809

I’m writing to settle accounts with those wearing masks in the fancy-dress ball called ‘human rights.’ —The Law of Sololand

Hassan Abdulrazzak

In TMR it’s rare that one knows personally the author of a book under review, but I was one of the writers featured in Iraq + 100, the 2016 speculative fiction anthology that Hassan Blasim edited and contributed to. We’ve since met on a few occasions. Blasim is a gifted storyteller both in conversation and on the page. I recall him telling me how sometimes he likes to write on his laptop in nightclubs with loud techno music in the background. Reading his work has the thrill of an adventurous night out on the town.

Sololand, his latest book, is made up of three novellas. It’s a raw, occasionally uneven collection, but one that cements Blasim’s place among the most essential chroniclers of Iraq’s post-2003 nightmare. These are tales of war, dislocation, and absurdity told with the surrealism of Kafka and the brutal satire of Irvine Welsh. But make no mistake: Blasim’s work is not imitation. His is a voice forged in exile, sharpened by survival, and steeped in the paradoxes of displacement.

The opening novella, Elias in the Land of ISIS, plunges us into Mosul at the height of its occupation by Daesh. Elias is a Yezidi teenager who must fake being a zealous convert to survive. He assists Abu Qatada, an elderly man who cooks for ISIS fighters inside the Clock Church, where they sleep beneath a shattered statue of the Virgin Mary.

Abu Qatada, it turns out, was raised by Dominican priests, fled Iraq, and then returned to rescue ancient manuscripts from the church — only to be captured. The story-within-a-story structure, with Abu Qatada telling tales by night, recalls Scheherazade and highlights the power of storytelling as resistance.

We also get to learn about the foreign fighters including the “couscous brothers,” French-Moroccan jihadists who often beg Abu Qatada to cook couscous for them, something that baffles him as an Iraqi because it sounds rude (kus means vagina in the Iraqi dialect). These moments of absurdity give the story both levity and edge. In Blasim’s Iraq, violence and farce are never far apart.

The real emotional core, however, lies with Sara, a pharmacist and poet forcibly married to an ISIS fighter. She closes her pharmacy in protest at jihadists buying Viagra — a detail that encapsulates a tragedy. Sara is fearless, opinionated, feminist — perhaps the most fully realized woman in the entire book. When Elias, Sara, and Abu Qatada plan to escape, the narrative grips with genuine urgency.

Forest Gump of Iraq

If Elias draws from Iraq’s hellscape, the second novella, The Law of Sololand, channels the refugee experience in Europe. The unnamed narrator lives in a “cruel, selfish, dark North” — a thinly veiled Finland, where Blasim himself sought asylum in 2004 after escaping Iraq.

The plot is layered and disturbing. After a scandal involving a rape by immigrants in a remote town, the narrator travels to the town of Sololand where the incident happened, ostensibly to finish a treatise comparing refugee lives to the life cycle of locusts. He meets Marko, a native activist who runs a “Refugees Welcome in Sololand” Facebook page with a meager 34 followers. Through him, the narrator is introduced to a program where migrants cook meals for locals in their homes — a symbolic gesture of cultural exchange.

But this encounter curdles into something far more unsettling. Suspicion and prejudice simmer beneath the surface. A seemingly generous host, Katerina, invites the narrator and his friends for dinner, only to reveal — through a slow unraveling of social codes — that the encounter is a kind of trap.

The novella hits a minor snag midway, when the narrator breaks the narrative to deliver a monologue — a direct address to other migrants cataloguing the indignities of exile. Though heartfelt, this moment feels heavy-handed. The forward momentum of the story stalls in favor of polemic. Yet even here, one senses a sincerity, a rage too pressing to remain buried in metaphor. Perhaps we are living in an age when the old adage “show, don’t tell” no longer holds absolute power. Sometimes the truth must speak directly.

The final novella, Bulbul, is the most sprawling — and arguably the most comic. Muhsin al-Bulbul is a former Artane-pill dealer from a poor Baghdad neighborhood now living in Sweden, recounting his chaotic life in post-2003 Iraq. His uncle rescues him from prison by enlisting him in a Shia militia called Ahbab Allah. Bulbul is assigned to manage a cleric’s email account, primarily to respond to female admirers. One such woman, Zainab, marries the cleric temporarily through mut‘ah, only to later attempt to seduce Bulbul himself, leading to his dismissal.

From there, he tumbles through a series of absurd careers: radio host, militia member, spy. He marries Karima, a woman who sighs constantly — a tic that becomes tragically meaningful later in the story. Blasim turns Bulbul into a kind of Forrest Gump of post-invasion Iraq — always near the action, yet never quite in control.

Iraqi Dialect

Jonathan Wright, Blasim’s long-time translator, notes in his afterword that Bulbul is written entirely in Iraqi dialect. That’s a bold move in the Arabic literary world, where Modern Standard Arabic still reigns in fiction. The claim that Blasim is the first to do so is hard to verify, however, because Iraqi writers are dispersed all over the globe and there is no authoritative survey of all their work. Blasim, for instance, has a great deal in common with my late uncle, the Iraqi short story writer Mahmoud Albayaty (1944–2014). Both writers have elements of the surreal in some of their stories, both capture the agony of the immigrant experience, both write protagonists that serve as alter egos, and both have been compared to Kafka. Yet Albayaty’s work is not as well known as Blasim’s, largely because it was published in exile prior to the fall of the Saddam regime and has not been translated.

Born in Baghdad in 1973, Blasim studied at the city’s Academy of Fine Arts and directed several short films, one of which — The Wounded Camera — criticized the regime’s treatment of the Kurds. He fled Iraq in 2000, journeying through Iran, Turkey, Bulgaria, and Hungary before reaching Finland in 2004, where he applied for asylum. Those years in transit — marked by fear, precarity, and absurdity — became the bedrock of his stories.

His first short story collection, The Madman of Freedom Square (2009), introduced English readers to his distinct mix of horror, humor, and surrealism. His second, The Iraqi Christ (2013), won the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, making him the first Arabic writer to do so. That book, and his later contribution to Iraq + 100, confirmed Blasim’s status as an adventurous kind of Arab writer, one who embraces experimental forms.

In the Arab world, his reputation remains contested. Some critics have dismissed his work as exoticizing atrocities. Others critique his use of language. Blasim anticipates some of that criticism in his fiction, and in Sololand he makes the case for the use of Iraqi dialect in literature through the character of Bulbul.

Sololand is a book about the redemptive power of storytelling. Some of Blasim’s protagonists use writing as a way to process trauma and make sense of exile. In this, they echo Blasim himself: a man who has turned personal upheaval into aesthetic innovation.

That said, the collection is not without flaws. When characters become mouthpieces for Blasim’s political views, the fiction wobbles. Yet even in these moments, there’s something compelling — perhaps because our era demands clarity as much as ambiguity. In Jasmine Naziha Jones’ 2022 play Baghdaddy, a young Iraqi-British woman breaks the fourth wall to deliver a political monologue. It worked. In a post-truth world, maybe readers and audiences now want stories that don’t flinch.

While Sara is a standout, most other female characters feel thinly drawn or filtered through a problematic male gaze. Bulbul’s fixation on women’s bodies — particularly their breasts — is likely meant to be comic or satirical, but it risks coming across as sexist, especially in a post-MeToo landscape.

Despite its uneven moments, Sololand is a vital, courageous and ultimately entertaining book. It rejects easy binaries of East and West, good and evil, victim and perpetrator. And it reminds us that literature, at its best, is a place where the marginalized can be given center stage and rendered visible.

Remarkable article