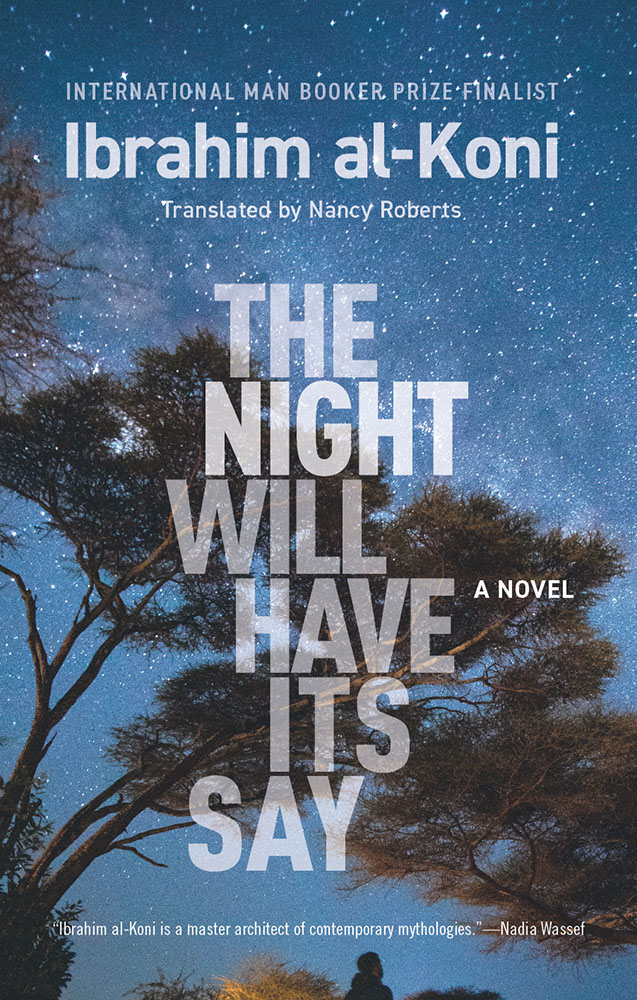

The Night Will Have Its Say, a novel by Ibrahim al-Koni

Translated from the Arabic by Nancy Roberts

Hoopoe/AUC Press 2022

ISBN 9781649031860

A damning alternative retelling of how Islam expanded into Amazigh North Africa by an authoritative insider-outsider voice

Iason Athanasiadis

An ominous prediction from the oracle of Delphi about the troubles about to befall the land of Libya, and a saying attributed to the Prophet Muhammad about how “nine-tenths of evil” come from the East, is how Ibrahim al-Koni embarks on a novel unsparing in its treatment of Islam’s early armies.

The standard narrative of the Islamic conquests involves swashbuckling Arab Muslims advancing across the known world, and attempting to win over hearts and minds to the new religion. But Koni chooses to fix his gaze on the plunder, revenge killings, vindictive taxation, kidnapped children, raped women and encompassing injustice justified by self-serving interpretations of divine rulings. And he highlights how, when they were not finding ways to engage in plunder (which ballooned into such a mainstream activity as for the word ghanima — “spoils of war” — to be formalized in religious doctrine), the purveyors of the new faith were often busy backstabbing each other. A poignant example of this concludes Koni’s novel.

Hassan Ibn al-Nu’man, commander of an Arab Muslim army and a man whose name is today prefixed by the faithful with the honorific hadhrat, spends much of The Night Will Have Its Say ruminating on his role, as he hesitates during a stalled advance in the no-man’s-land of Barca (today’s eastern Libya), biding his time before a final confrontation with his great adversary, the Amazigh leader Kahina.

The seer Kahina is the leader of North Africa’s indigenous Amazigh community, and the suitably tough product of a matrilineal society. She is a cruel yet farsighted strategist in seeking to pump vigor back into her society’s bloodstream by destroying its cities, a general in how she marshals her subjects, and a mother in the manner that she tries to “overcome enmity among the world’s peoples by commingling their blood.”

Although they are never to meet, the magical realist sequence of mental exchanges between Kahina and Nu’man form the nucleus of a novel examining the fading of a people who were vanquished militarily (but also culturally) by the unstoppable advance of monotheistic and monocultural modernity. The psychology and inner struggles of Nu’man plays along Kahina’s personality, who becomes ever more aware of her own and her people’s demise as the novel progresses.

This is a rare book, both for the voice it gives the traditionally marginalized Amazigh, and the unorthodox thoughts it dares express in a censorship-riddled and taboo-strewn literary scene.

So who is author Ibrahim al-Koni and what impelled him to take stances so extremely critical of Islam and Arab authoritarianism?

Both stateless and exiled

Koni was born stateless in a Saharan oasis in 1948, a few years before a UN referendum brought Libya into existence. He is not Arab, and from the context of this novel, which punctures the foundational myth of Islam by portraying the first ghazis (“warriors”) as little more than rampaging booty-seekers and rapists, he does not appear to have a high opinion of Islam, at least in its mainstream practice.

An ethnic Tuareg (one of the many communities of the Amazigh), Koni grew up in the medieval trading crossroad of Ghadames, located in modern-day Libya, in the years immediately following World War II. The mudbrick town was once a caravan station, and today huddles in a patch of desert where the corners of Libya, Tunisia and Algeria meet. One of the world’s masterpieces of desert architecture, Ghadames saw its extraordinary bioclimatic urban web restored by UNESCO just before the 2011 revolution in Libya. But it is also empty, following the forced relocations of its inhabitants, initially by former Libyan leader Muammar Ghaddafi (who moved them to a collection of air-conditioned, flat-topped cement buildings as part of his modernization drive) and in the early 2010s by Arab Islamist militias carrying out a racial purification drive. When this writer visited Ghadames in 2013, some of the Salafist fighters who had driven out the Tuareg from the city were already setting off for Syria in order to wage jihad against the Alawite Bashar al-Assad, as they put it.

“I was driven out of my paradise as a young child,” Koni lamented in an interview, referring to Ghadames. Subsequently, his books — which recreate a lost world of desert dwelling — have been translated into 40 languages. Koni was named a finalist for the 2015 Man Booker International Prize.

“Even if I were a prophet, I would not have managed to write sixty books about it [Ghadames] from memory…So in order to make this beloved of mine present I have had recourse to memory of another kind, what the Sufis, the Islamic mystics, like to call ‘inner memory’ and psychologists refer to as ‘the unconscious,’” he said.

Despite only learning Arabic at age 12, Koni went on to become one of the most awarded authors in Arabic today. Rather than viewing the desert as a bourgeois escape hatch from civilization (increasingly how urban Arabs choose to experience it), Koni evokes the balance it brings to its remaining residents.

As a young man, Koni worked in Tripoli as a journalist. His political dissidence soon drove him out of Libya to the Soviet Union, where he studied comparative literature and philosophy. He worked as a journalist in Moscow, founded a literary magazine in Warsaw and, shortly after communism’s collapse, moved to Switzerland for twenty years, then Sweden, and onwards to Spain, where he lives today.

As time passed, the anti-authoritarian symbolism Koni injected into his novels became more overtly political. In 2011, he praised Mohammed Bouazizi, the Tunisian street vendor who sparked the Arab Spring by immolating himself after a routine incident of police harassment, as “a saint… the Christ of our time” who “bore his cross and sacrificed his life.” Gaddafi’s fall followed (with a helping hand by NATO) but rather than a happy ending, Libya segued into ripping itself apart in an ongoing orgy of violent turmoil.

From his perch in Spain, Koni acts as the voice of the stateless and voiceless Tuareg. He relentlessly reminds us in his books and interviews that Tuareg isolation and their traditional lifestyle in the Sahara were exploited to deny them the twin agencies modernity requires: a recognized state and language. Instead, French colonialists occupied Tuareg areas, subjected them to years of withering nuclear tests, before divvying up the land between Algeria, Libya, Niger and Senegal, none of whom acknowledge Tamasheq (a variant of Amazigh) as a formal language. Koni likes to remind the world in interviews that the Sahara is humanity’s cradle, and that therefore the Tuareg deserve a better fate than their current one.

The Islamic conquest

In focusing on the Islamic conquest of North Africa, The Night Will Have Its Say identifies the key turning point in Amazigh loss of agency. Koni views Islam as neither enlightening nor civilizing, but as the purveyor of a corrupting modernity that taints the purity of animistic culture.

Kahina, the Amazigh queen, has a greater ambition than just defeating the Arab Muslim invaders: she hopes to end racial competition through creating a mixed race, a “reconciliation among the races through the magical mediation of motherhood.” But as the Arab troops approach, her project shifts into a confrontation between a matrilineal society and Arab patriarchy. Koni writes:

“How was she to exact revenge on people who made a profession of igniting wars when, as everyone knows, in wartime all is lawful, and the copies of the Quran raised high on their spear tips were nothing but an excuse to amass blood-drenched plunder?”

As the Arabs edge closer, Kahina institutes a scorched earth policy, cutting down the forests that offer respite from the Sahara’s furnace. “She ordered her men to cut down its trees and raze its fortresses, destroying every remnant of civilization and vegetation alike… in the belief that wiping the Shade off the face of the earth would shield her from the Arabs, who had only come out against her out of greed for a civilization they had forfeited in their own homelands.”

But Kahina is also fighting an internal rearguard action against her own people’s compromises. Many have ceased their nomadic life to urbanize. She has “no sympathy for people who, to her disgust, were content to spend their days lolling in houses of clay and whose affinity for life in the Shade had extinguished the flames of heroism in their hearts.”

Although she will never meet her conqueror (and his conquest will come through betrayal), Nu’man, they share this instinctive distrust of the urban: “I have avoided living in cities for fear of falling captive to these very customs,” he notes. “I refused to live in Kairouan (an Arab garrison city developed after the conquest of the territory that is today’s Tunisia), or claim my share of the booty or take concubines. I didn’t want to give myself a taste of luxury, lest wealth be my demise, as it had been for so many.”

In the end, Koni shows that it is money that makes the world go round: the new religion becomes an empty vessel, exploited by booty-seekers to enhance their reach. A few sensitive outsiders, like Nu’man or the dervish Hanash Sanaani, hold onto their values at the cost of swift marginalization. Ultimately, Koni signals to us that the fate of the person who chooses to remain authentic, whether in the 7th century or the 21st, is to be violently pushed aside.