Sarah Ben Hamadi

“Home Sweet Home.”

Few people know that John Howard Payne, the American author of this famous expression, which has become popular around the world, lived and died in Tunis, where he served for a decade as U.S. Consul. I myself only found out very recently, during a BBC report on the consular district of the medina in Tunis, yet I have always lived in the Tunisian capital.

Tunis is a city with a thousand and one facets, and a thousand and one secrets, which we discover every time we walk the streets, even if we have lived here all our lives. As French Tunisian journalist Amira Souilem described it in a recent report on Radio France International, Tunis is a bittersweet city par excellence. In my view, Tunis is sweet by virtue of its magnificent light, bitter by its often dirty streets; sweet by the beauty of its old art deco buildings, bitter by its anarchic stalls; sweet by the patience of its inhabitants, bitter by their often difficult daily lives — a city of contradictions, where everything intertwines to create its charm.

In Tunis, it is impossible not to succumb to the charm of the medina, classified as a world heritage site by UNESCO, and its magnificent residences, despite their sometimes dilapidated state. But if the interest of tourists, historians and architects is often drawn to this unavoidable district of the capital, the so-called “European” city center, which was built by the French during the era of colonization, does not lack interest or charm. Delimited by what is called Bab Bhar (Sea Gate), or “Gate of France,” which separates it from the traditional medina, the city center is the beating heart of the capital.

When we think of the city center’s downtown area, we often think of the stalls of the Avenue de Carthage, its central market with its beautiful colors, the lovely Cathedral of St. Vincent de Paul Avenue Bourguiba, and the imposing Ministry of the Interior, symbol of the police state of Ben Ali. This was where, on January 14, 2011, Tunisians came to assert their anger and shout “GET OUT!” to a self-installed authoritarian president who had ruled for 23 years.

Today, walking in the heart of the city, beyond the art deco and art nouveau buildings — built between the 19th and 20th century and as attractive as they are dilapidated — we cannot but cast our gaze at the walls, now invaded by graffiti and street art.

That’s just as well, because in Tunis you have to look at the walls to understand the situation. These walls, which were so white before 2011, have become the logbook of the city. In fact, just as it inspired John Howard Payne with his poems in the 18th century, Tunis today inspires young artists who set out to reclaim it by making its walls speak.

In Tunis, the walls have much to say

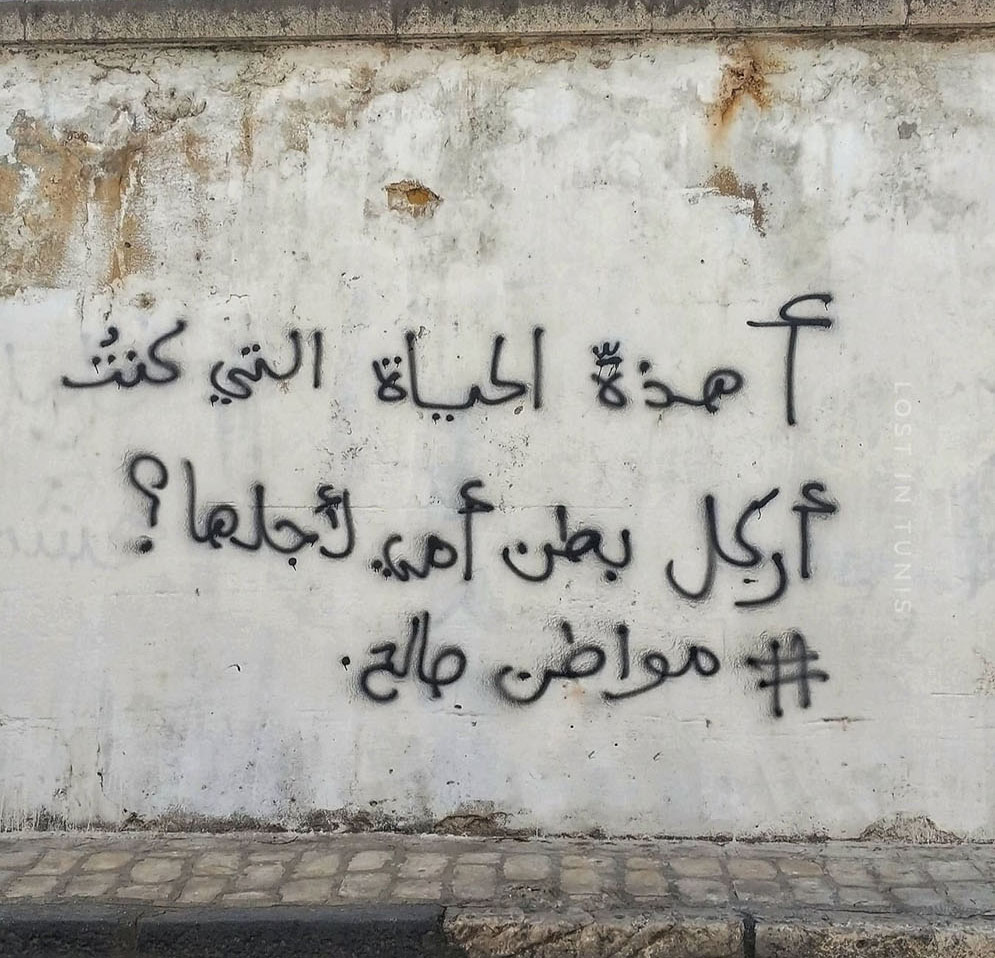

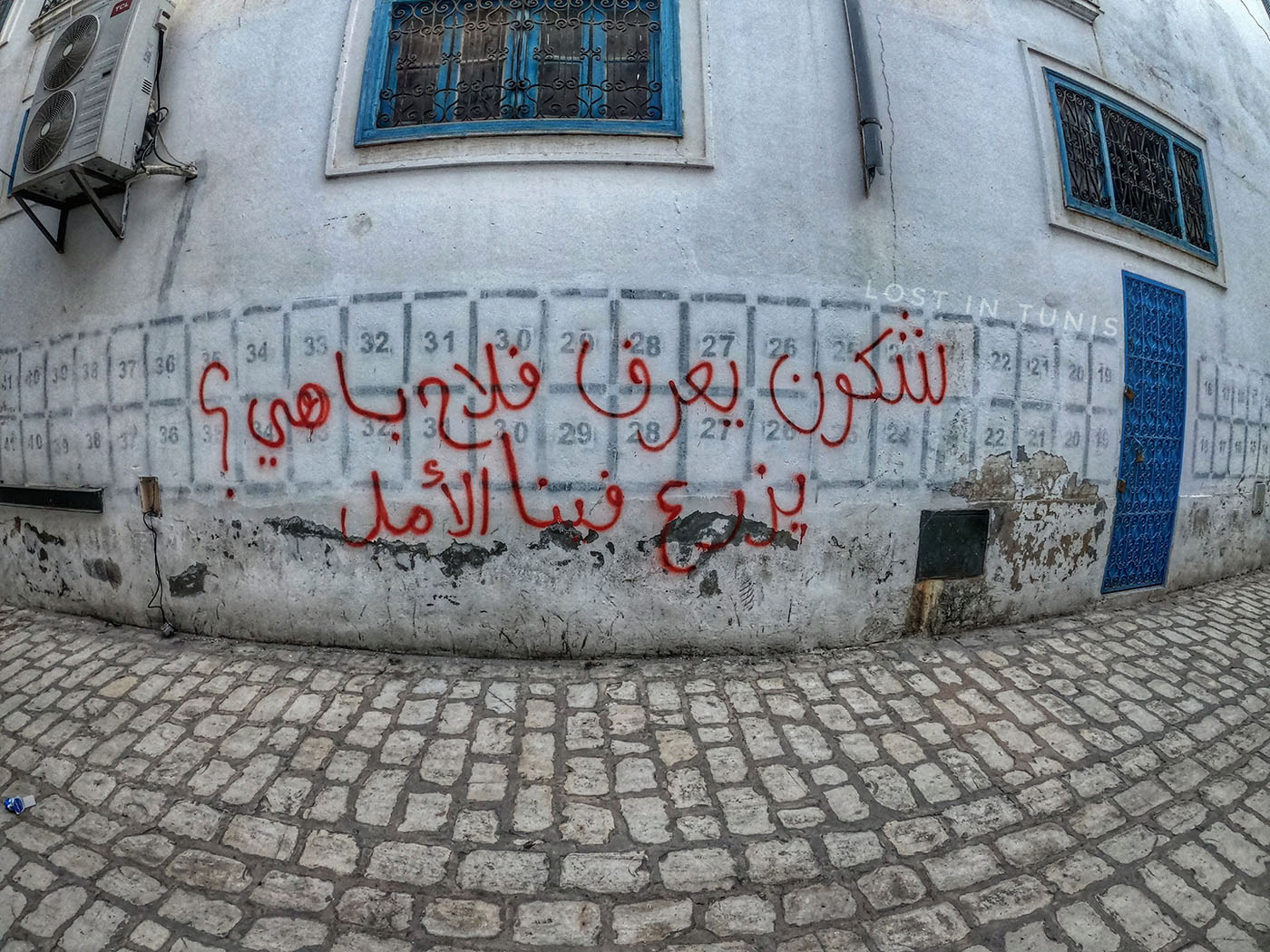

Since the popular uprising of 2011, the walls of Tunis have spoken volumes. They tell and trace the daily life of the city. Young street artists have appropriated these walls and, through their work, made them a sounding board for society.

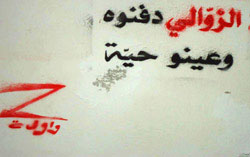

Several artist collectives have sprung up during the past decade, their members sharing their dashed hopes, their discomfort and their slogans on the walls. Such is the case with Zwewla (“the poor” in Tunisian dialect), a collective of anonymous anti-system taggers whose signature Z is recognizable as the avenging Z of Zorro, and whose objective is to raise awareness of social injustice with clandestine tags.

Social tolerance for these illegal tags following the revolution failed to dissuade the local authorities from arresting two of the collective’s graffiti artists, Oussema Bouagila and Chahine Berriche, in Gabes (southern Tunisia) in 2013, accusing them of spreading false information and undermining public order. The case created controversy because it was considered an attack on freedom of expression in a period of democratic transition, where revolutionary achievements remain fragile. Perhaps for this reason, Bouagila and Berriche were quickly released and fined a mere 100 dinars ($30).

A mode of expression considered subversive, ephemeral and in constant renewal, street art allows people to contest, denounce and shake up social codes in the public space. For a decade now, the walls of Tunis have served as a forum for communication on issues of social justice.

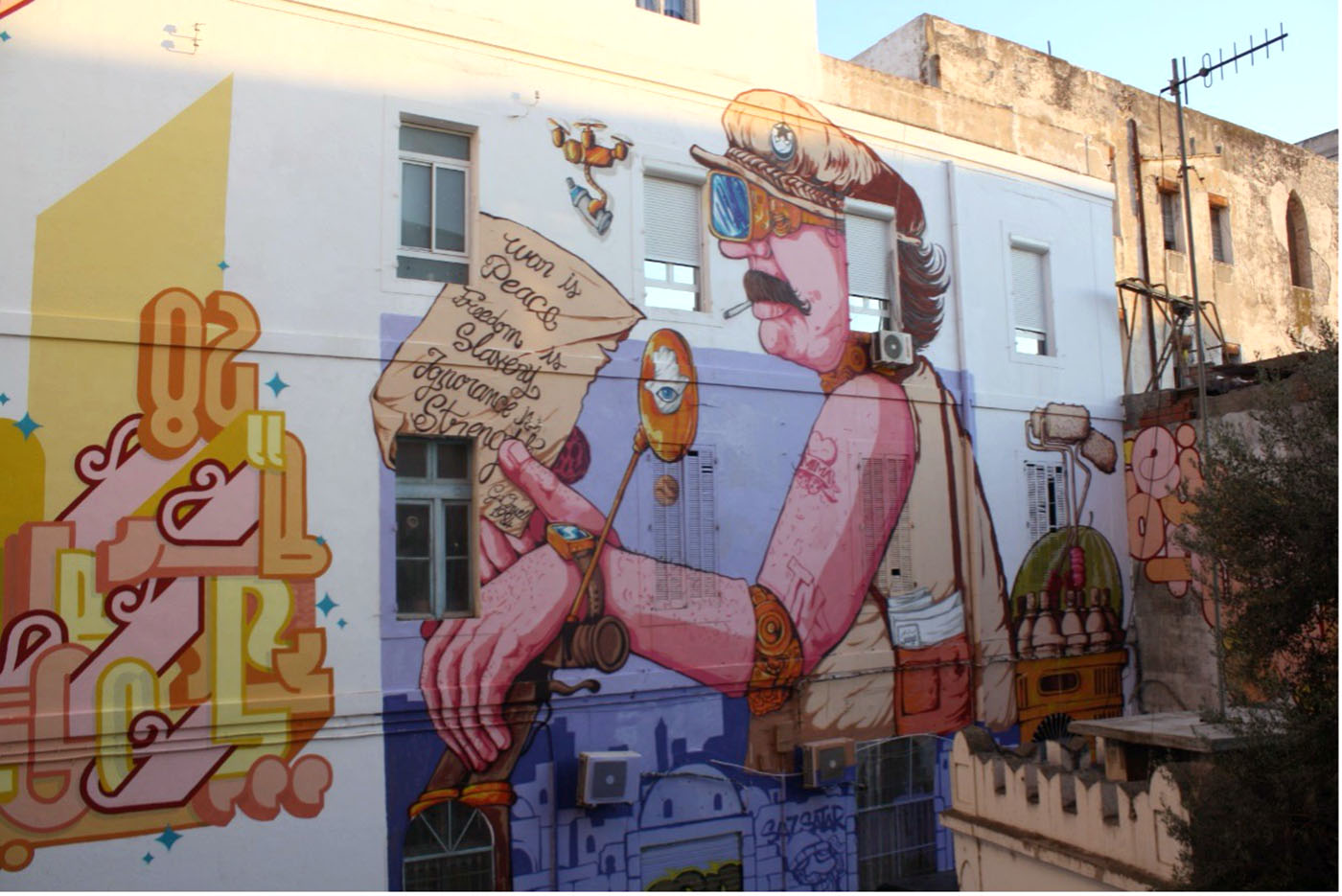

But are artists obliged to convey a message through their works? Not necessarily, according to Mehdi Ben Cheikh, artist and owner of a Parisian gallery specializing in urban and contemporary Tunisian art. Organizer of numerous projects both here and there, such as La Tour Paris 13 and Djerbahood (street art project in the island of Djerba in southern Tunisia), Ben Cheikh explains that “there is no mandatory message in art. Painting in the street is already a political act in itself.”

Lost in Tunis

Defining himself as an urbexer, Mourad Ben Cheikh Ahmed, amateur photographer, likes to get off the beaten track in order to (re)discover forgotten and lost corners of Tunis. With his camera, he archives the city from all these angles on his blog Lost in Tunis. Ahmed has observed Tunis over the years and documented its evolution: “The graffiti have become much more politicized; the level has evolved too,” he says. “We went from tags on the sly to well-developed frescoes or concepts. There are teams…They put in more resources. Some murals take more than a week of work for a team of taggers, so rich are they in detail.”

And indeed, unlike the first clandestine tags that we observed a few years ago, today the walls are covered by giant frescoes, with multiple social and political messages.

Art made accessible

We can also observe this renewed artistic interest in downtown Tunis manifesting itself in a framed way, through the mushrooming of new art galleries in the capital. Some galleries, such as 32 Bis and Central Tunis, have revived neglected areas in the heart of the city. Others are based in areas such as Sidi Bou Said and Marsa.

Thus, the walls of the former Philips factory, built in 1953 in downtown Tunis, became the hybrid art space 32 Bis. This is a spacious gallery of some 4,000 square meters, fitted out and transformed — on a street known for the sale of tools and spare parts, where art traditionally has had no place — “in order to create links with the inhabitants of the district,” according to its director, Camille Lévy. 32 Bis coheres with the neighborhood and lends space to an artist such as Atef Maatallah. He painted a giant fresco representing the workers of the construction site who contributed to the redevelopment of the factory into a gallery. Maatallah observes that many neighborhood passersby are uncertain that such a grand gallery really is for them, but the fresco is an open invitation. “[My work] allows all these people to know that they can come inside,” he says.

A few streets away, on Avenue Carthage, near the iconic Barcelona Square train and bus station through which thousands of Tunisians pass every day, the Central Tunis gallery was inaugurated in 2018. It’s an impressive cultural project, to be sure, intended to serve a wide range of viewers and art lovers from all social classes, while making art more accessible.

Founded by Emna Ben Yedder, Mehdi Tamarziste and Arij Kallel, in collaboration with Soumaya Jebnaini, Central Tunis proposes artistically challenging but financially accessible art, and supports both established and emerging artists. As Emna Ben Yedder explains, “Each time we have an exhibition, we ask the artists to propose variations of certain works that will not hurt the artist’s price range but which, by proposing another type of work, can be sold at a lower price. Thus, one can find at Central lithographs, engravings, serigraphs or collages. This gives a greater number of art lovers the possibility to go home with something to call their own.”

Ben Yedder, who has been very involved in revolutionizing Tunisian society since the ouster of Ben Ali in 2011, considers Central Tunis’ mission to celebrate the joy and freedom of art while straying from the beaten path, proposing painting, photography and installations that search for meaning. Words that come up in conversation with Ben Yedder are “free,” “experimental,” “liberated” and “joyful.”

A catalyst of Tunis’s new urban dynamics, the creation of art in the heart of the city is in turn integrated into the mutations of the latter. And so, for the past ten years, the city has been undergoing a subtle transformation, through artistic movements and projects, individual and collective, clandestine and legal. It is a transformation that pushes back the walls of classical cultural institutions and makes art more accessible. It is also a vestige of Tunisia’s struggling democracy.

Thank you for this valuable text.