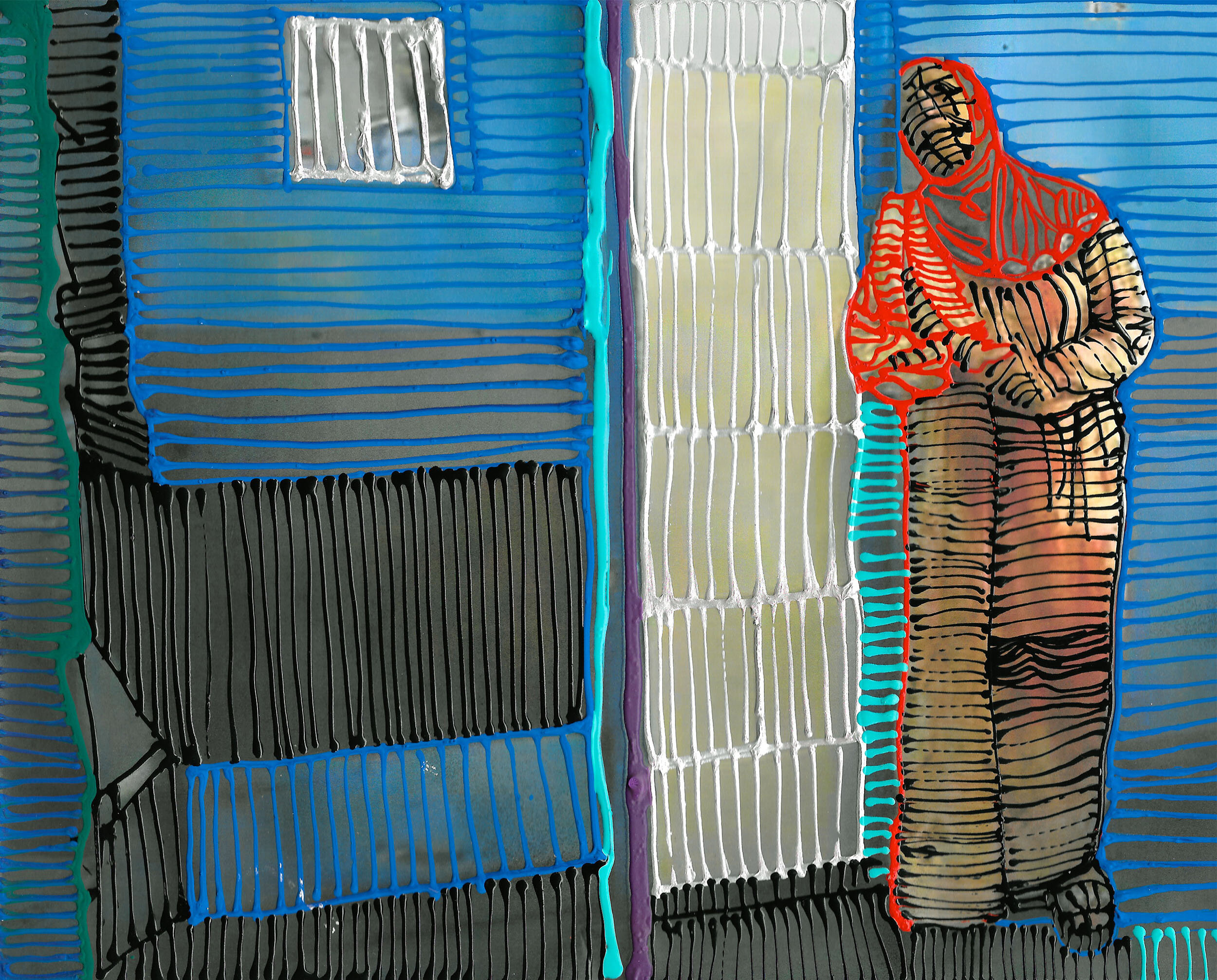

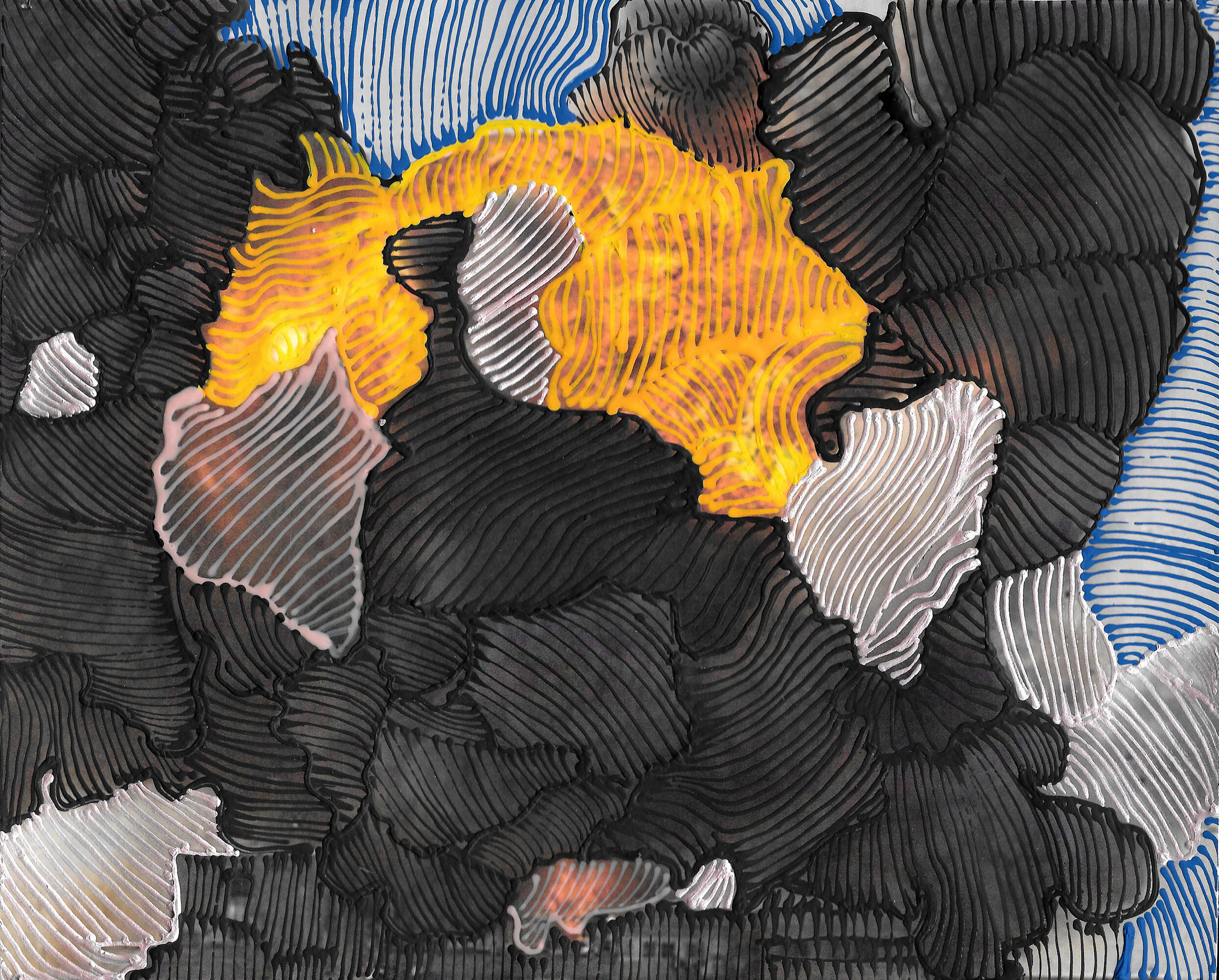

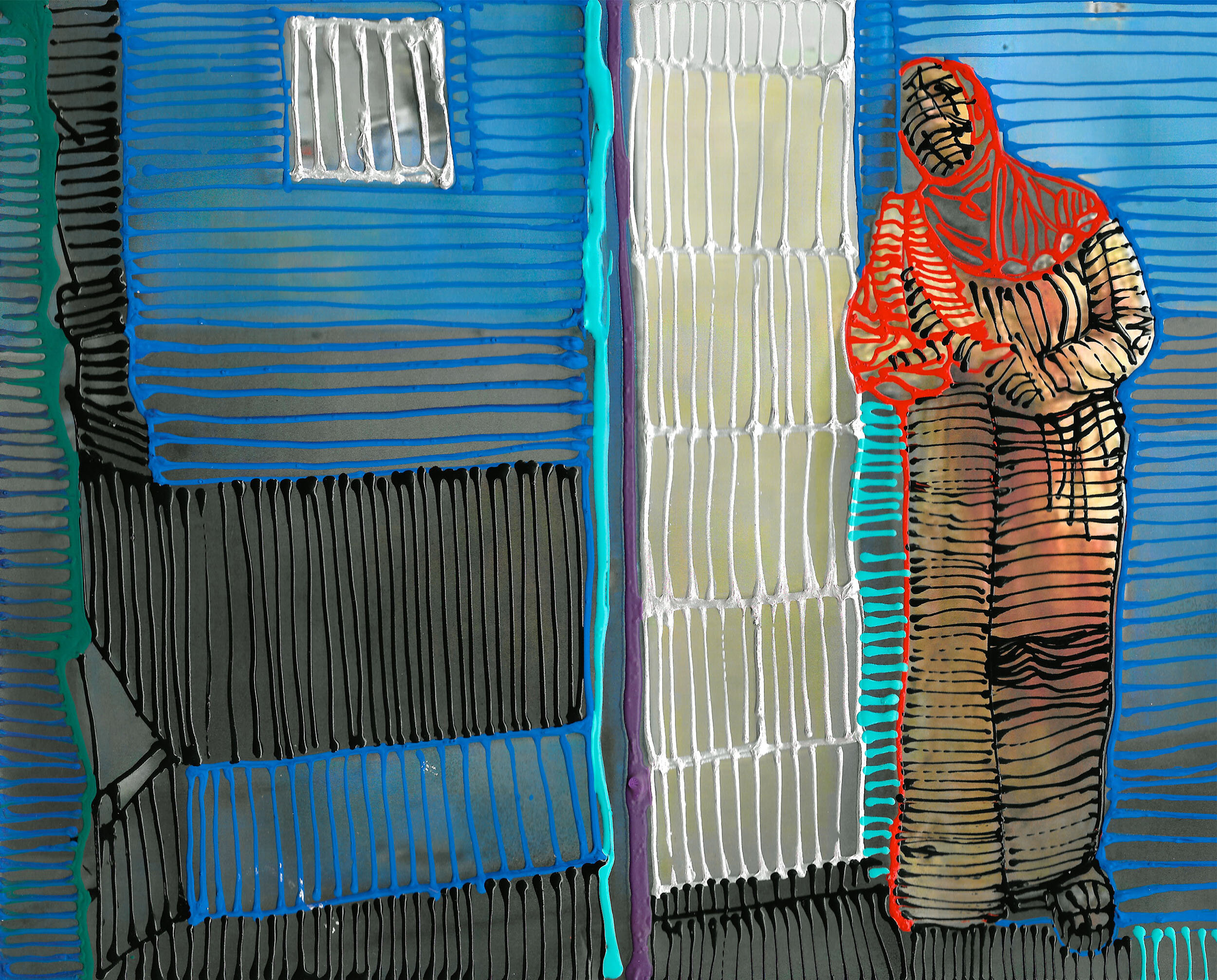

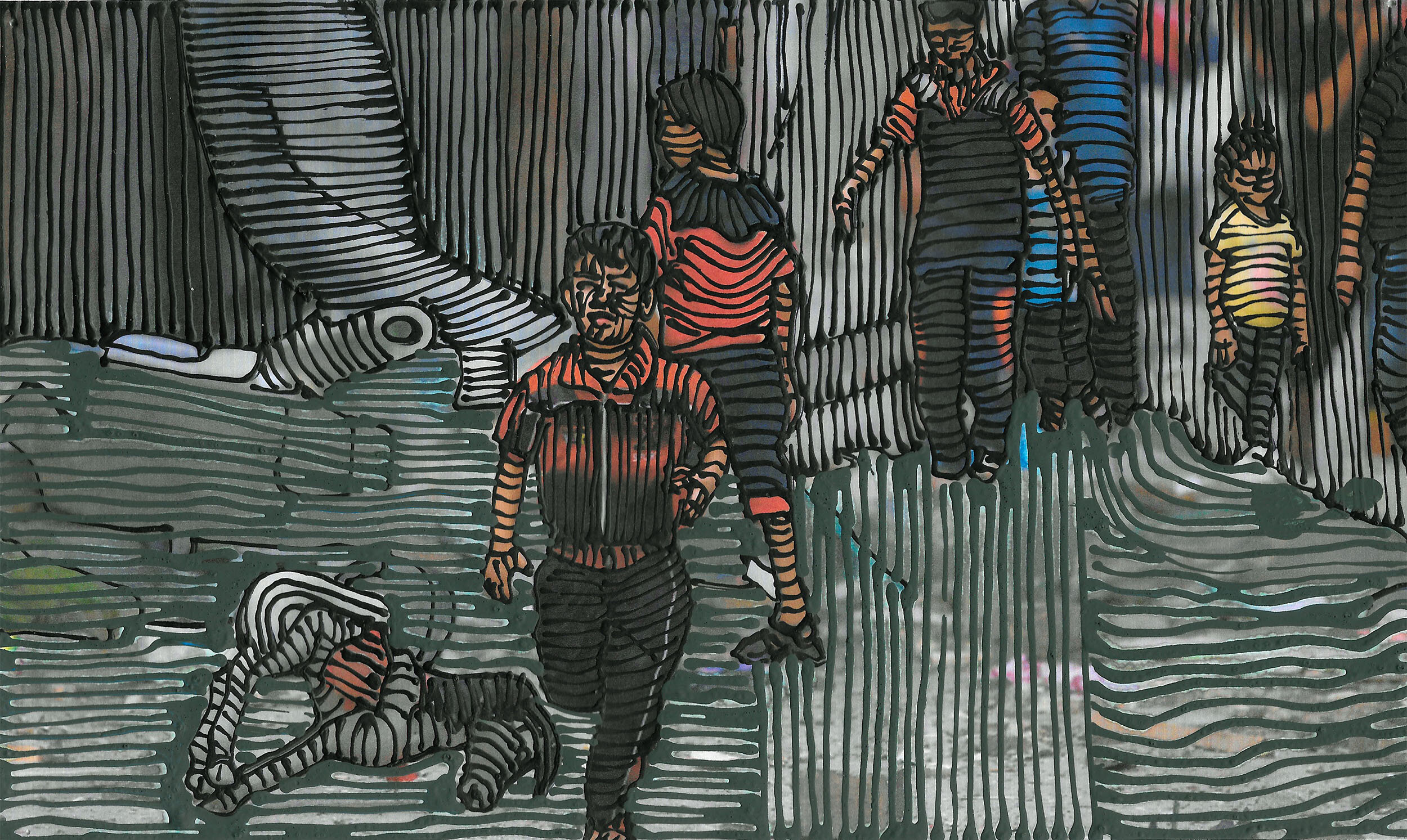

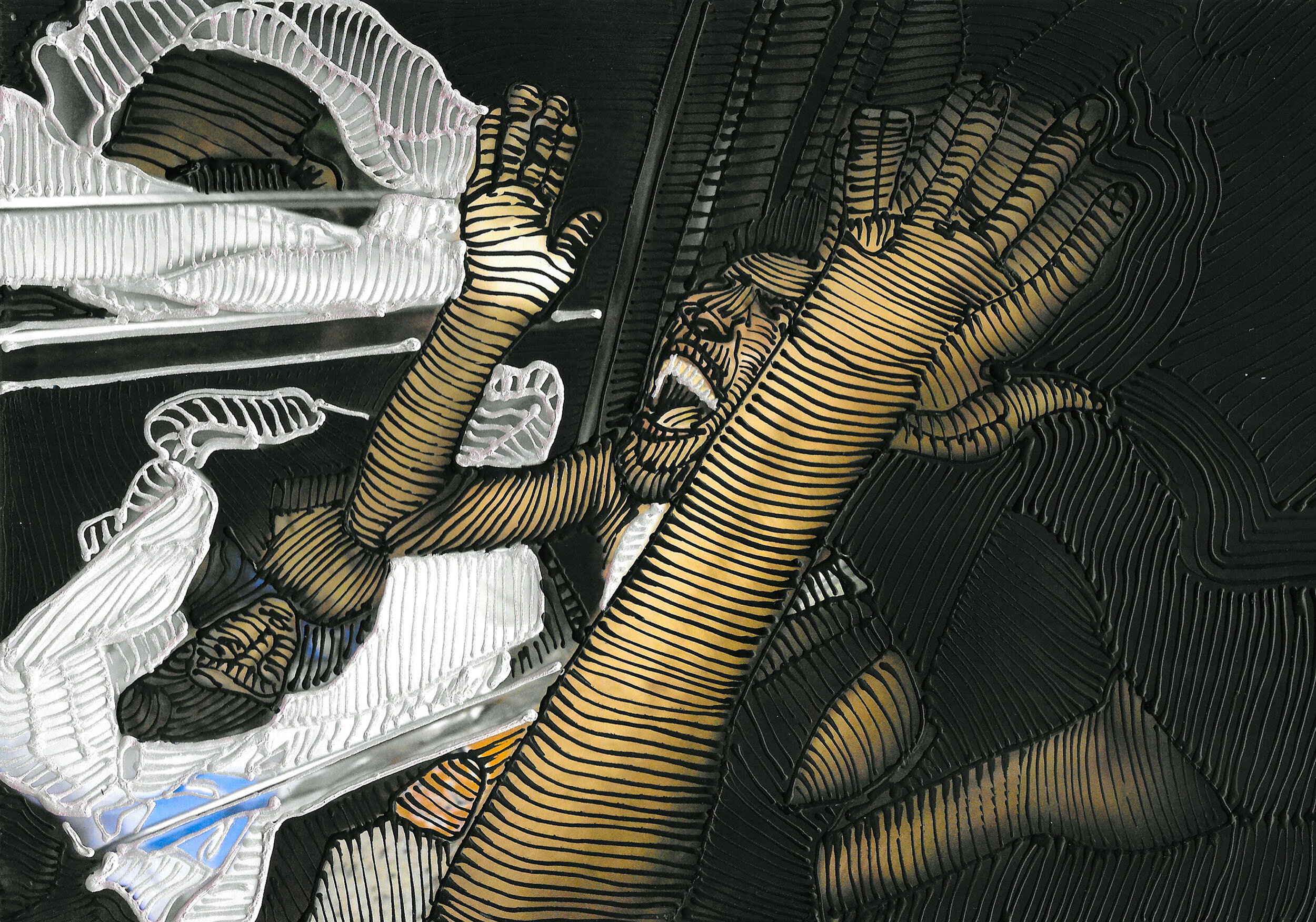

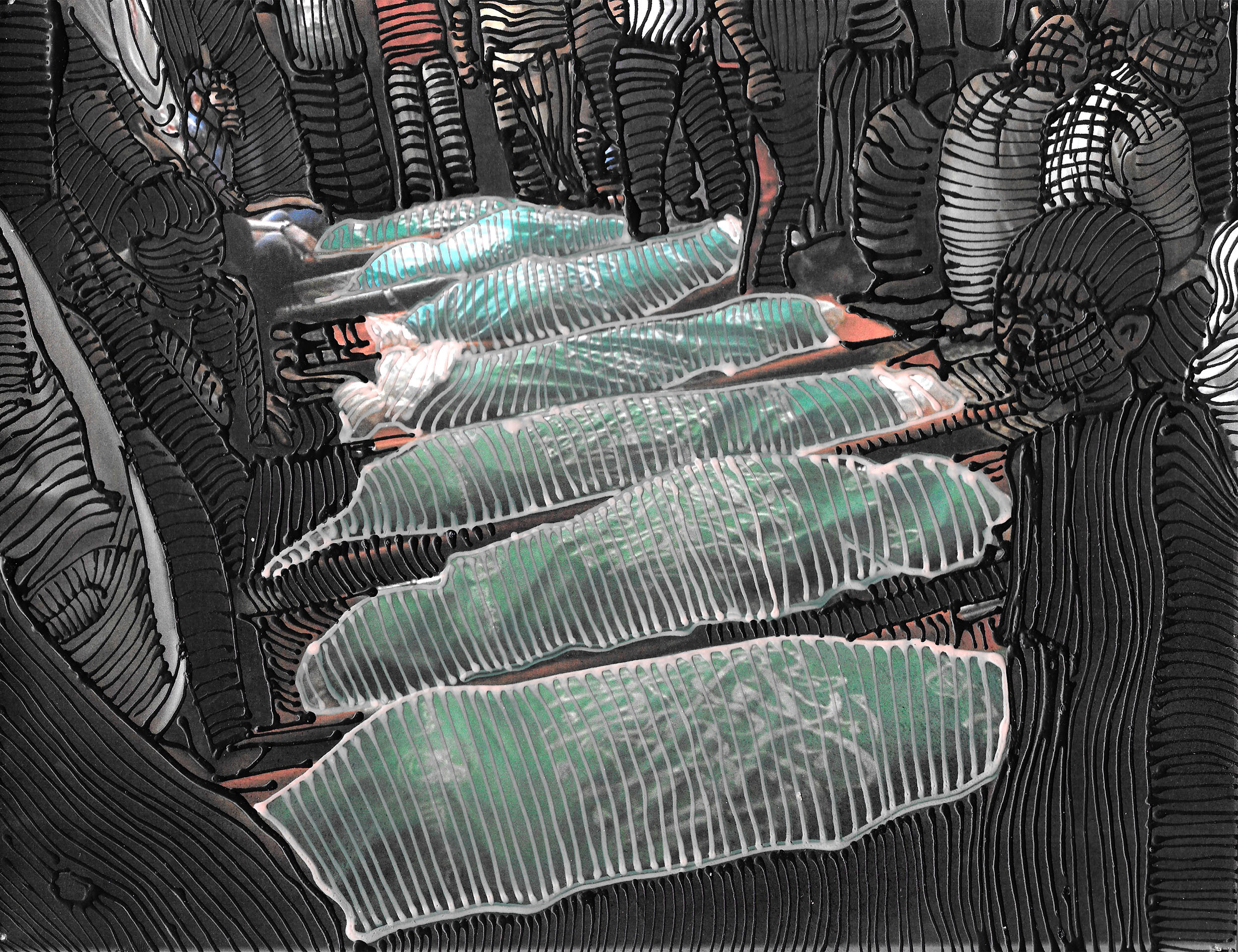

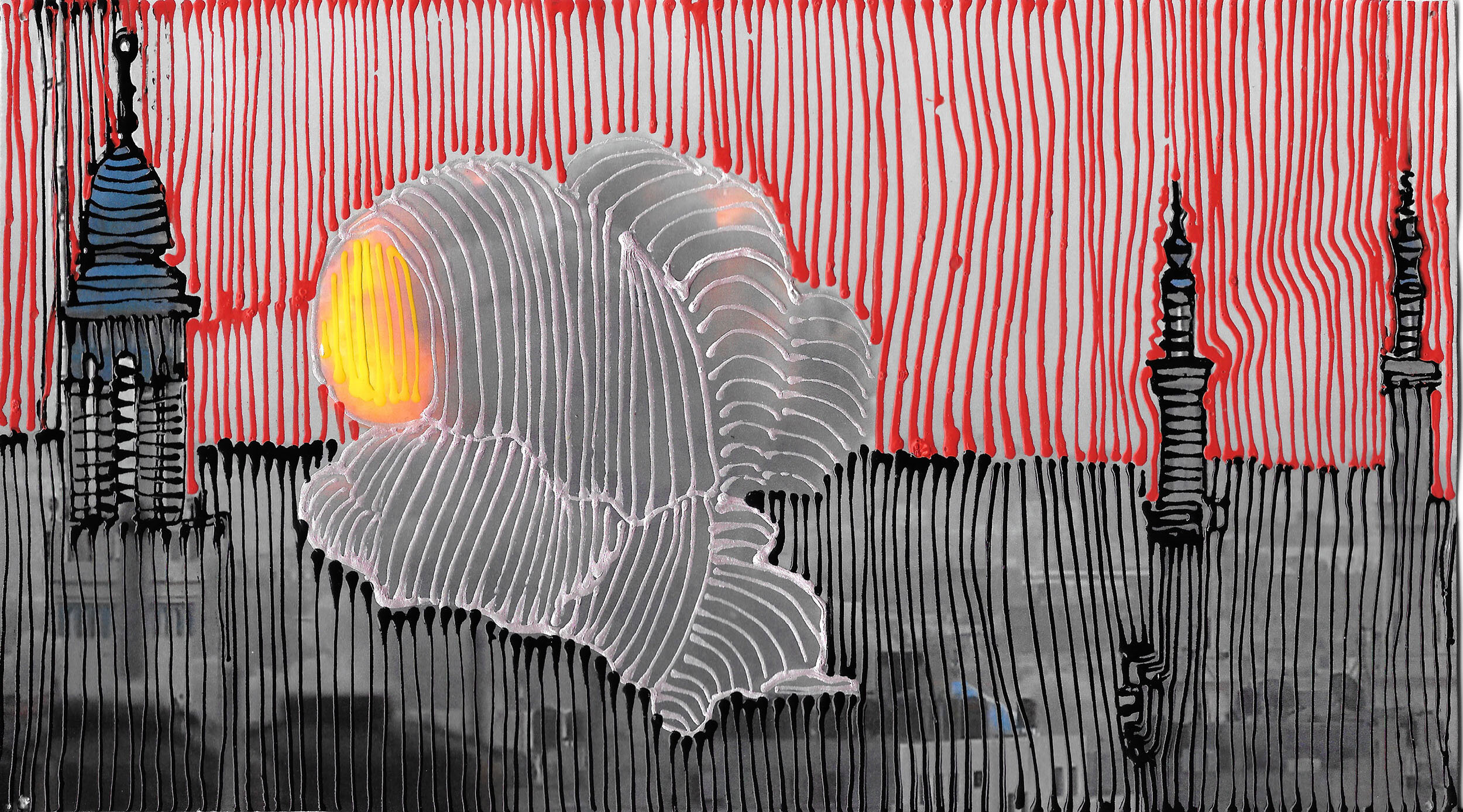

The July-August 2014 asymmetrical war that Israel called “Operation Protective Edge” left over 200,000 Gazans homeless with more than 2,000 killed. Hearing about the onslaught on the news in Los Angeles, while it was happening, artist Jaime Scholnick wanted to turn away. She says, “The images that came across my newsfeed through social media were horrific. At first, I was angry at these postings and would pass them by. After two days I stopped and made myself look. I felt the need to document this latest atrocity on the part of the Israeli military. ‘Mowing the Lawn’ is a term they coined to describe the periodic assaults they conduct on Gaza to keep the Palestinians under control. By covering these images with multiple lines and colors, the imagery becomes easier to look at, not less horrific.” —Ed.

Sagi Refael

In her book Regarding the Pain of Others (Penguin 2003), Susan Sontag suggests reversing the common perception of “peace” as the norm and “war” as the aberration, to what they really are — war as a contentious condition, and peace as a rarity.

In other words, we are accustomed to war; we imagine peace. Sontag continues by quoting Leonardo Da Vinci’s opinion that, in order to create a provoking and sublimely beautiful work of art, the artist’s gaze at its subject should be pitiless, as evident in many early Christian masterpieces depicting the crucifixion and the Pieta. Yet, Sontag claims, it seems heartless to look for beauty when it comes to photography, a medium that brings the horrific sights from the war or the scene of the crime “directly.” That kind of photography, it is commonly agreed, should not be beautiful, since it distracts the attention from its subject matter to its framed aesthetic medium.

Jaime Scholnick’s “Gaza: Mowing the Lawn” is one of the most significant politically-charged art series of recent years. Not only because of the direct reference to one the world’s endless and violent ethnic and religious conflicts between the Israelis and Palestinians — but because of its precise capture of the current Zeitgeist, the spirit of our times. It seems that we are at a high point in history, where we can know so much, yet prefer not to know as much, and easily turn a blind eye.

Gallery Exhibit: Gaza: Mowing the Lawn

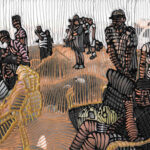

Scholnick’s 2015 installation at the CB1 Gallery in downtown Los Angeles consisted of 50 acrylic on paper works about the size of an iPad or a page in a small book. 49 of them were placed on a gray painted strip stretched on the corner of two walls, which evokes the barrier of the Israeli West Bank and seems to symbolize a blocked horizon; a fence of indifference that this presentation strives to penetrate. Situated on the opposite wall was a singular piece, the 51st, by itself, that captures a group of civilians who seem to be watching the live show of the Israeli Air Force spreading its devastation across the other side of the room.

During the Israeli bombing on Gaza in the summer of 2014, images of the destroyed city emerged online, painfully shared on social media outlets such as Facebook. Those images from a remote land in a too well known war zone were difficult to consume and digest for many, including Israeli society at large. The Israeli media shielded its consumers from images of dead bodies and destroyed family homes, uniformly presenting a picture of a “no other choice” victory. Israelis who stood against the massive attacks on Gaza were marked publicly as traitors by politicians and many brainwashed citizens. All criticism had to be put aside; it was us or them; no tolerance for varying shades of gray.

The 2015 Los Angeles exhibition of “Gaza: Mowing the Lawn” (photo courtesy Electronic Intifada).

Several of Scholnick’s friends advised her not to focus on the tragic circumstances of the victims and surrounding destruction. Some even asked her which side she supported. As it often takes at least two to tango, the Palestinian rocket attacks on the Israeli population, which caused less immediate damage and casualties, were depicted less in the international media. Neither are they evident in Scholnick’s work here. After the press release presenting “Gaza: Mowing the Lawn” was issued, feedback included complaints that the “full picture” was lacking — not including Israeli victims, both civilians and soldiers, and ignoring the ongoing violent attacks on Israel by Palestinian terrorist organizations.

But what is “the full picture,” and is it the artist’s responsibility to depict it?

In our technology-based “time is money”driven society, most of our image consumption is shaped by split second viewing, understanding and opinion forming. Scholnick’s installation, based on popped up images in the ephemeral online media, bring forth an awareness to whatever is going on in the Middle East, while reminding us in this part of the world that these events don’t really have an immediate relevance to our daily lives.

These images get the same attention, if not less, than breakout Hollywood gossip or Washington politics, functioning as a checkbox for our social conscience… We know that something horrifying is still happening over there, but thank God it’s happening to total strangers, far, far away.

A Response to “Gaza: Mowing the Lawn” by Tony Litwinko

Scholnick retrieved these images daily from social media outlets and printed them at home, then started carefully painting on them, covering the pictures with colorful, patterned lines. At first, these lines camouflage the hard to look at views, luring the audience in with the guise of colorful abstract drawings. After capturing the spectator’s attention, she forces one to gaze into the core of the image, into its realism of human suffering. By repeatedly marking horizontal and vertical lines, day after day, on top of the documented reality of destruction, it feels as if the artist is mending the broken and dead, wrapping the scattered human limbs with a metaphorical, healing bandage.

In some cases, the scenario is not completely clear. But in most of the pieces, the composition repeats itself over of over, refusing to be a dry reportage of cliché journalism — demolished houses, toys scattered on ruins, funeral after funeral, mourning, sadness, despair. While we might prefer to swipe these violent images aside in an endless search for the new, Scholnick forces us to slow down, stop, look, think, concentrate, analyze, and comprehend.

The shallow criticism over this body of work was not for how the artist treats the topic of war, but for depicting it in the first place. Not to mention that “criticism” from an inner circle Jew, which destabilizes the defensive wall of righteousness, should not be heard in public. At the same time, it is easy to imagine criticism from the Palestinian side for appropriating the suffering of their people, and for “beautifying” it, partially covering the whole truth.

But “Gaza: Mowing the Lawn” goes beyond referencing the singular case of Gaza. These works comment on the way we consume and refer to war and misery — as a flood of images that we view from a safe distance, and yet the more we can see, the less we want to know. Instead of allowing us to keep war in the abstract, Scholnick insists on presenting her audience with hardcore facts, swathed in a see-through veneer.

Jaime Scholnick lives and works in Los Angeles, California, where she continues to create art addressing global and domestic concerns. The artist received her BA from California State Sacramento and her MFA from the Claremont Graduate University in 1991. Her work has been included in institutional presentations as well as galleries in Asia, North America and Europe. She was commissioned by the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority to create a 400 ft. mural for the Crenshaw Expo Station on the new line to the LAX Airport which will open in late 2021. In 2020 Ms. Scholnick was commissioned by the Los Angeles County Department of Art to create a 20′ x 42′ mural to adorn the exterior of one of four buildings of the newly built LAC + USC Restorative Care Village on the KECK USC Medical Center Complex. This newest piece will be installed August 2021. It is an homage to the Boyle Heights Community. She lives and works in a studio in East L.A.

While horrific violence has always existed throughout history, nowadays depictions of war and violence have become more familiar, and their consumption has become more pornographic (ISIS-filmed beheadings, for example). As Sontag argued, “shock can become familiar, shock can wear off”; the attraction to violence becomes a norm in an escapist society, whether for entertainment (violence in movies and on TV) or for subconscious enhancement of self-esteem (personal and national). These images from Gaza are not of violent action, but the results of it.

So why are they hard to look at? Because they reprimand us silently for our own comfort and security — for looking at them in a pristine gallery or on a flat computer screen from the safety of our own homes. They remind us that we hardly do anything to protest against or intervene and prevent these recurring horrifying events from happening again.

“The problem is not that people remember through photographs, but that they remember only the photographs,” Sontag declared, stating our habit to detach the image from its source and its original accurate reference. By using the pictures as a plane on which she builds her visual statement, Scholnick’s transformation of these images from Gaza into works of art causes their circulation to go beyond the frame of the daily or weekly news arena into the timeless frame of culture.

Following Goya’s “The Disasters of War,” Picasso’s “Guernica” or Leon Golub’s post-Vietnam war oeuvre, the subject matter of war and its consequences in “Gaza: Mowing the Lawn” becomes bigger than its specificity. By including an image of ISIS soldiers directing their guns onto a baby’s head, Scholnick blurs the lines between the different victimizers. While they remain remote and faceless, the victims of violence and war become all victims, of any violence, in any culture, of any time.

While these representative proofs might not hold the commander’s finger from pressing the next trigger or button, these artistically-altered pictures serve as both tools of remembrance of past catastrophes, and, despite the gap of time and place, a personal “Memento Mori” for the viewers of the fragility of their own lives.