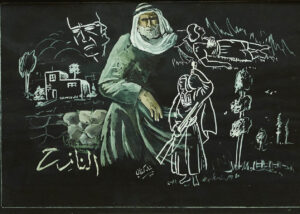

A writer reacts to the 51 painted photographs by artist Jaime Scholnick in her 2015 exhibit in Los Angeles, “Gaza: Mowing the Lawn,” following Israel’s brutal 2014 Operation Protective Edge, the onslaught on Hamas and Gaza that cost many lives.

Tony Litwinko

You cannot go there now, and when you were there in 2009 it was too brief to take it all in. Barely twenty-four hours. Yet the first impressions are still strong. The broken American School, the demolished cement plants, the apartment buildings with their folded floors and rubble sliding into the streets as if from a scoop, a plastic tent covering a family, the administrative building with the burned windows on the third and fourth floors, its blackened walls where the missile had entered precisely. The divided boulevards with the donkey-drawn wagons with auto tires, the vista down to the Mediterranean. When you were in Gaza six months after Operation Cast Lead, the rubble was still there, the holes in the stucco, and yet: you could stand on that boulevard separated by a dusty divider with broken trees and imagine what peace might bring — a seaside vacation spot with thriving tourism, the beach down below the hotel looking out over a rebuilt tiny harbor like the one in Jaffa, the fisherman casting for an unpolluted dinner. But now all you can remember — no, because of pictures you imagine — are children playing soccer on the beach in 2014 then struck by shells from offshore and torn apart.

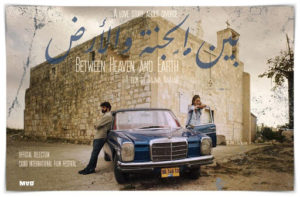

Visit “Gaza: Mowing the Lawn” and read a critical review of the exhibit.

In the gallery where the artist placed her exhibit, your first impression was that these are so small, so dwarfed by the wall on which they hang, double rowed, leading to and around the far corner, so that you have to approach and zoom in as if you were on Google maps to drill down and look hard at these images, barred and threaded and strung instruments of grief, the screams and wails silent, the fierce steadfastness, roads to nowhere passing between disintegrating rubble. Dead children, dead mothers, the screaming fathers, the dead children.

But go closer. These taut threads of color keep you from seeing the images in their journalistic mode, truly the size of the news photos they are built on, providing only the slimmest of narrative for this most recent of Israel’s vicious attacks on the Palestinians enclosed in Gaza since 1994-96. Haven’t you had enough of those photos by themselves? Haven’t you seen, since the Vietnam War, the naked torment of a running girl scorched in a napalm flash? Or some other version of her? Of the father holding his dead child in a pink bathrobe in Baghdad, her spindly leg dangling from a tendon. And for us, the empathizers, seeing their inner pain of loss?

When you stand back you see them as photos no longer, but you know the stories are behind the bright primary colors, the way reality is behind the images. The way death is immediate in the arms of the loving survivor in pain, or the fear of another death that brings the scalpel in the white gloved hands of a surgeon excising shrapnel from a child’s gut.

For almost all Americans these 51 images have evaporated in time. A picture for each day of the war, now hidden by fast currents of the news — so here, says the artist, here, work into your commitment, struggle with it, because you must know that only those who feel the empathic pain, that is, only we Americans who have rejected the clichés of the media (“terrorism,” “the right to defend themselves”) are coming to this gallery to experience the grief of these condemned and brutally ignored victims and defiant steadfast Gazans. It seems at moments like these that only those who know want to know more, want to see how someone else knows, how an artist knows.

Ironic, is it not, that all of us who have come to see these images understand and assume that it is not a member of AIPAC next to us shaking his head in grief. We know that Hillary Clinton will not be here. We know that Haim Saban will be off electronically transferring funds to the Friends of the IDF. They will not be looking at the images of Jaime Scholnick, although we wish they were.

These photographs bear witness to the latest violence against this concentration of ill-nourished and captive people, classified by their prison administrators, as if they are vegetation, growing and growing until “the lawn must be mowed.” The Israeli thug who first used the phrase “mowing the lawn” has dehumanized the Gazans as if they were a cosmetic nuisance for a slumlord who wants to keep things neat and trimmed and manageable, who does it with machinery, blades of shrapnel, weed whackers with wings and missiles supplied by his US benefactors.

Operation Rainbow (2004). Operation Days of Penitence (2004). Operation Summer Rains (2006). Operation Autumn Clouds (2006). Operation Hot Winter (2008) Operation Cast Lead (2008-2009). Operation Pillar of Cloud (2012). Operation Protective Edge (2014) aka Operation Strong Cliff (“Miv’tza Tzuk Eitan”). Nine years after Israel bussed out the illegal settlers to help reinforce the occupied West Bank settlements, stationed its Gaza occupation soldiers around the Gaza border fence, its Marines out in the Mediterranean, its helicopters and drones and American-supplied fighter/bomber jets in the air above the destroyed Gaza Airport (and then insisted that it was not “occupying” the Gaza Strip) — nine years after that withdrawal Israel launched its last and most vicious infiltration, “mowing the lawn” of the 27.4 square mile Gaza Strip — including, of course, the almost half-kilometer wide killing strip inside the fence that nullifies a good deal of Gaza’s best agricultural land, that is to say, the soil farthest away from the encroaching salt water of the sea.

Come with me, my fellow Americans, come with me for a tour of this proscribed acreage. You won’t as a private citizen enter Gaza easily. I know. I have friends who have been patiently waiting for years. So let us enter Gaza as a photograph, courtesy of Google. You can find the perimeter fence easily, and then see how the perimeter road runs on the Israeli side, how the land to the West looks spotty and greyed, with some patches of green. But to the East, observe the Israeli farmland, green, blue-green and yellow-green butting right up against the perimeter road. Observe the difference in action. Patchwork fields like in the American Midwest or all over the world, and an occasional irrigated circle. Observe them from Sderot in the northern edge to Kfar Aza, Alumin, Kfar Masrion, Be’eri, Re’Im, Kissufim, Nirim, Magen, Yedea, Ein Ha’Besor, Yesha, Nir Yitzhak, Holit — down to the Egyptian border, all these settlements or villages created since 1948, or having been occupied, renamed — and you will see that the land within the fence could be very productive for all. Could be feeding Gazans. Could be producing exports to the EU. Rolling agricultural land.

Please observe how Google gives us bonus photos, ironically usually without people, since landscape images seem more serene without them. Does this remind you? Click on Nir Yitzok to see the photo of a purple iris in front of a field of mustard and trees in the distance, as if this were a pastorale. Scan the “Phoenician Style Modern-art Colonnade” with greening hills in the distance covered with trees from the New Israel Fund. Check out the “Wonderful World of Beery Vale” filled with idyllic grass. Or the “Green Road Border of Gaza.” Click and you will see cultivated land on the Israeli side. Is this not wonderful scenery?

And in the same exercise observe how you can safely hop over the fence without an entry permit to see a plume of evil smoke issuing from a fire near the Gaza power station. Could this be from the July 29th tank attack on the fuel depot near the plant? (Google maps never says.) That was the attack that in turn disabled the water treatment facilities for Gaza. The plume is ugly, thick and black. The shadows of the smoke stacks fall on the ground. There are patches of plowed land within the Gaza confines — as far away from the encroaching polluted sea as can be and edging right up and into the no-man’s land where brave farmers and belligerent frustrated shouting youth are shot for their livelihood or their defiance. And as more than one person has commented, notably Noam Chomsky, the no-man’s land could have been placed on the Eastern side of the border fence. The No-Man’s land is a systemic encroachment that drives us nuts when we know the reality. In Sara Roy’s revised edition of The Gaza Strip: the Political Economy of De-Development, she reprints a warning from the Israeli “Defense” Forces and a rough translation (p. xlvii): “To the People of the Strip: The Israel Defense Forces repeat their warning about the danger of approaching within 300 meters of the borderline. Henceforth, the Israel Defense Forces will take all necessary measures to eliminate anyone who gets close to the zone. If necessary the IDF will open fire without hesitations. No excuses will be accepted now that you have been warned.”

Google maps will show the detail but not the motion and life needed to understand the texture of ruin and rubble, death and pain, defiance and terror. We can only go so far into the pixels of the image or the pointillist graphics of a news photo. One pixel equals a smashed bedroom.

So, let us return to the gallery of the chosen scenes of Gaza.

The artist emphasizes the borders of empathy, and has deliberately added to the limits of visualization, reminding us that you have to be there to understand the 2014 onslaught on Gaza, reminds us, shows us what we will see when we zoom in — the anguished father’s eyes clenched tight while his clenched fists rend his jalabiyah; a father tenderly carrying the corpse of his eight year old; mourning families; anger and frustration; blackened corpses lying in sheets; a screaming father near the drawers of a morgue that hold his wife and children. Is there not enough sadness? Then think of the children. The children. And then there is too much sadness.

If in those 51 days of terror, of “mowing the lawn” — and I know how some religious people of conscience will recall Isaiah’s “all flesh is grass and all its loveliness is like the flower of the field. The grass withers and the flowers fade when the breath of the Lord blows upon it” (40:6-8) — and no doubt well-read partisans of self-defense will see in this most recent mowing of the lawn that the Israeli onslaught was like the “breath of the Lord.” Perhaps that will be the military title of the next mowing… Operation Breath of the Lord.

Because you know, the Lords of the Land, as they have been called, appear in Scholnick’s last picture element, which she has made to stand alone on its own wall. Apart. Distant. But always there.

And by this means of separation the artist makes the final commentary on the lords of that constricted land. She shows Israelis enjoying the show as if they were on a hill above a Fourth of July celebration in this city. We zoom in and see the calm figures of Israeli photographers and sightseers on the hill outside of Sderot, looking down on the plumes of smoke and destruction, but at a safe distance, lords of the land looking down on the out of sight flesh as if it were grass, being whipped and shrapnelled to blood and entrails, far, far off in the distance, where the explosions are immediate and lethal but the blast is heard much later. Please note the seconds of silence between smoking reality and sound. Observe how you never, never hear the screams of the children.

Me interesa este contacto. Soy artista visual de la República Dominicana

Impresionante relato..increíble en pleno siglo XXI un genocidio trasmitido por la redes sociales y no hacemos nada!!!