Exclusive excerpt from The Handsome Jew, a novel by Ali Al-Muqri

Translated by Mbarek Sryfi

Dar Arab 2022

ISBN 9781788710879

The Markaz Review bookgroup will discuss The Handsome Jew, moderated by Rana Asfour and with translator Mbarek Sryfi, on August 28, 2022. Info.

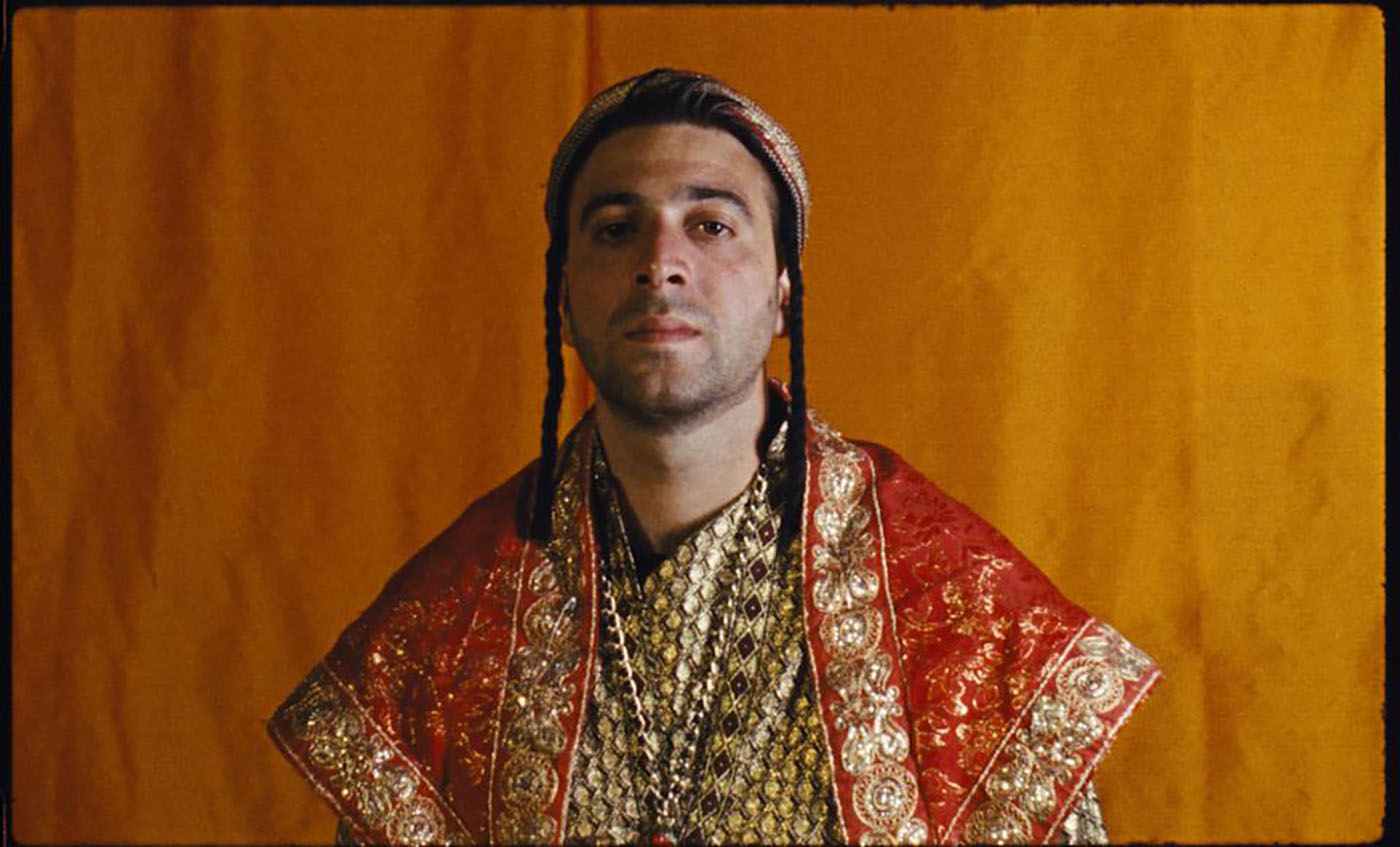

Ali Al-Muqri

And then it was the year 1054 AH (AD1644 -1645), during which, after the wind of years had crushed me and death debilitated me, I decided to record these stories about Fatima’s days and her time, up to this year when I married a dream, and we had twins: hope and catastrophe.

It all began seven years ago. Over the course of those years, I did some chores for her family, and they rewarded me, generously, with whatever they had, be it corn, bread, or candy. At first, I didn’t like the idea of going to their house. I would spend most of my time with my new friend, a dog I picked up as a puppy in the street without its mother’s knowledge; I branded the tip of its ear with a knife and called it ‘Allus.

I wasn’t able to take it with me until the third time. That day, my father asked me to carry some firewood to the mufti’s house, which was how the man was known in the village of Raydah. My mother picked out a pile from the sticks she had gathered from the mountains, tied it up with a tree- fibre rope, and put it on my head. I dragged my dog along. He would stop whenever he saw something moving. But with the dog beside me, I didn’t feel the weight of the wood the way I had the last two times.

Amat al-Raouf skilfully ignored us, both boy and dog. Her sister Fatima would usually open the door when she heard me yelling “Hello there! Anyone home?” She would then take me to the third-floor roof, where the family cooked and baked bread. There, I would deposit my load, with ‘Allus waiting patiently all the while by the front door.

By the time my eyes began to open a bit, as I fought the prickly pain on my head, Fatima would have unfurled her smile all over the place. She would linger, before getting me whatever her father, mother, or she herself decided to give me for what I’d brought. Even before that, she would lift up my spirits.

“What a strong man!” she would say to praise me, and go on to pray, “God bless you… May He make you rich and strong… may He protect you!”

“May God keep you young and bring joy to your years” were words that made my day, complimenting my coming of age, while everyone else around me insisted on reminding me that I was younger than her. I was twelve at the time, and, according to my mother, she was five years my senior.

Many times, Fatima would give me a cup of tea and gaze at me in admiration. I didn’t know what attracted her. She would rarely say anything. Sometimes, she would hold my head and pull my face to her waist, or she would bend over and touch her chest. Once there, she’d whisper, “What’s wrong? What’s the matter?”

2

One morning, she surprised me. She announced that, the next day, she was going to start teaching me to read and write. With that in mind, I had to get ready to spend every morning with her.

“Don’t they teach you at home, my handsome Jew?”

I felt my stomach flutter as she tenderly and flirtatiously articulated those words, which I wasn’t used to. Was I her Jew? Her own Jew. Not only that, but, in her eyes, I was handsome. Not knowing the meaning of reading and writing, I answered her question with a shrug.

At home, I asked my father about it. He explained that the sayings and prayers he used in his invocations were found in old manuscripts, that they were recorded on tablets, parchments, and papyruses for those who knew how to read, by those who knew how to write. He himself did not know how to read or write, he told me, but he observed the prayers and heard the sayings and hymns from other people who had heard them from the ancestors.

When I told him that the mufti’s daughter was going to teach me reading and writing, he looked stunned. He stared at me for a long time without saying a word. Long minutes elapsed before I heard him mumble something indistinctly to himself.

That night, he woke me up. “Listen to me very carefully. Learning how to read and write with them is all good. But…be careful. Make sure not to learn their religion and their Quran…they are Muslims, son, and we are Jews…do you understand?”

I nodded. Yet, the next morning, he repeated what he had said. He handed me a leather bag covered with lambswool, in which he put a clay tablet for writing, a ceramic inkwell filled with a vivid brown liquid, and a stick resembling a tooth-cleaning miswak for writing. For erasing, he gave me a piece of silk like a small pillow, filled with cotton, that you wet when in use.

As Fatima welcomed me, her expression was full of delight. She invited me to their long room, which they called the diwan, and there we sat facing each other. She began writing on the tablet, “S…A…L…E…M…Salem.” I relished my name as her lips enunciated it. I felt like someone stumbling onto his name and existence for the very first time. She held my hand as she taught me how to draw the letters and say them aloud.

“Handsome,” she told me after that first lesson, “very handsome…You’re so smart!” “Now, what would you like?” she went on with a smile. “Do you want me to write your name as ‘Salem the Jew’ or ‘Salem the handsome,’ or, you know what, ‘the handsome Jew’? What do you think?”

I shrank back, not knowing what to say. I simply lowered my head, so that my eyes avoided hers.

“The handsome Jew, then,” she said. “I know you like it when I call you that.”

She spelled out the letters of my name and my new moniker, and she kept repeating them in a tone that sounded like chanting.

That is how I started getting lessons from her every morning. First, she taught me the alphabet, from Aleph to Yaa’. Then she taught me how to connect two letters or more to form a word, “Father, mother, free, affection, love.”

When I started writing and reading in complete words and sentences, she brought a book with colored writing, which she asked me to read. I saw decorated words, interlaced and dotted letters, in a wide font that made reading difficult. But, as soon as I heard Fatima’s voice reading them, I learned them by heart.

As a matter of fact, what I learned by heart was her voice, not the words, which I could never match. Her performance of them, in a melodious voice, drew me in and amazed me. I kept on repeating them in the same style, either in front of her, on the road, or at home:

By the sun and its brightness,

And by the moon—when it follows it, And by the day—when it displays it, And by the night—when it covers it,

And by the sky—and He who constructed it, And by the earth—and He who spread it,

And by the soul—and He who proportioned it.

I also enjoyed other words:

By the morning brightness,

And by the night when it covers all with darkness, Your Lord has not taken leave of you,

O Muhammad, nor has He despised you.

And the Hereafter is better for you than the first life.

And your Lord will give unto you, and you will be satisfied. Did He not find you an orphan and give you refuge?

He found you lost and guided you,

And He found you poor and made you self-sufficient. So as for the orphan, do not oppress him.

And as for the petitioner, do not repel him.

At home, when my father heard my voice as I recited those words, he almost lost it. He kept standing up and sitting down, coming and going back and forth, yelling, “Oh God Almighty…Oh God Almighty.” My mother tried to calm him down while asking him what was the matter.

“What’s wrong? He’s just repeating Arabic hymns, talking about the sun, the moon, and providing for orphans.”

He raised his voice, “What’s wrong? What are you saying, whore? This is the Quran…This is the Muslim’s religion…They’ll ruin the boy…They’ll ruin the Jew’s son… They’ll ruin the Jew’s son…Oh God Almighty…Oh God Almighty!”

Our neighbor As‘ad heard him and called out from his roof, “What’s going on, al-Naqqash? What’s happened?”

Soon, he pushed open the door to our house and asked again. What he learned was soon known to the whole neighborhood.

Even though it was nothing, what Fatima had done was like igniting a fire in the Jewish neighborhood. She had just taught me how to read and write.