Gaza is reminiscent of the military campaign against Raqqa. While combatants might change, carpet bombing of Middle Eastern cities is nothing new.

Ammar Azzouz

Wars of our time, sometimes fought in our name, are not in the trenches; they are fought street-to-street, house-to-house, one home after another. Why does a hospital, a kindergarten, always seem to be hit in every outbreak of hostilities? After nearly four decades of reporting on conflict, I now often say: Civilians are not close to the frontlines; they are the frontline.

— Lyse Doucet, BBC Chief International Correspondent

For over a decade now, the built environment in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Libya has been radically transformed through the mass destruction of cities and villages and, before them, many cities throughout different times in history, such as Warsaw, Coventry, Hiroshima and Sarajevo, have been destroyed due to human conflicts and wars. The relationship between the built environment and violence, wars and conflicts has been widely researched. This increasingly growing body of research has focused on different lenses to theorize the geographical shifts of urban conflicts towards cities, their spatiality and their political causes and consequences. The built environment within cities, towns and villages has become the site of battlefields and contestation as conflicts have moved beyond conventional armies.

As Saskia Sassen notes, nowadays, major cities are likely to be the frontline during wars, which is different from the two World Wars when large armies needed skies, oceans and fields to fight. The shift of conflicts towards everyday spaces has meant that an entire way of living has collapsed. Residents find themselves at the heart of conflict. Tanks enter their neighborhoods, snipers occupy their buildings and fighting groups knock down walls across homes to access the neighborhood. In war on cities, soft targets such as bakery shops, schools and local markets are attacked, making every day life a war in itself.

In contested cities, dividing lines emerge to control people’s mobility and separate communities from one another. Public spaces become contested about who has the right to access them and who can protest in these spaces. Conflict infrastructure such as walls, fences, buffer zones, cement blocks and checkpoints emerge spatially within the built environment to segregate communities and create sectarian and homogeneous geographies. With the emergence of these dividing frontiers, even infrastructure projects including main roads and train lines become sharp dividing edges between communities.

Urban studies “as a discipline has been surprisingly slow to analyze how the experience of cities in the ‘South’ might cause us to rethink urban knowledge in urban theory,” writes Colin McFarlane. This also applies to the urban violence research that has been geographically limited. Mona Harb highlights the need to diversify the perspectives of urban studies on the city at war. She explains how current urban studies on conflict “very much privilege cities of the global North, while cities at war elsewhere are less explored, even though they are increasingly the target of the US and Europe’s defense strategies, as well as the testing ground of many of the military and informational technologies implanted in policing and securing urban neighborhoods.” These limitations are reflected by the lack of writing about cities that went through radical destruction in the aftermath of the Arab Spring in countries such as Libya, Yemen and Iraq. There is a little scholarly work on what happened in these countries and how cities have been reshaped by long-term conflicts.

An example of this lack of knowledge is the destruction of Raqqa, a Syrian city that has become synonymous with ruins and urban misery. Between June and October 2017, the city was the site of mass bombardment by the Global Coalition led by the US (it included several forces, e.g. UK and France.) With thousands of airstrikes within the four-month period (including 30,000 US artillery rounds), at least 1,600 civilians were killed and 80 percent of the city has been reduced to rubble. The destruction included residential areas of people’s homes, leaving tens of thousands of buildings uninhabitable.

Raqqa is an example of a city that has been destroyed by foreign powers, but to date no academic research focuses on the city and its destruction. Other cities, including Gaza, Misrata, Deir ez-Zur, Mosul and Taiz remain underexposed despite all the losses each of these cities has endured. Other cities that were bombed and destroyed by foreign powers have been the focus of some academic research, such as the case of Belgrade which was bombed by NATO in 1999.

This lack of studies on cities among the post-Arab Spring cities contrasts with the writings on urban violence in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks in cities such as Brussels, Paris and London. The main question that should be asked is why do scholars on urban studies focus on certain contested areas and why do they avoid cities destroyed in the Arab region? Does this align with the “First” and “Third” World prejudice where some lives and cities are less valued than others?

Domicide: The Destruction of Home

Whilst a growing body of work has emerged the past decade on the relationship between the built environment and violence in Syria, little attention has been focused on the consequences of destruction on impacted communities. In Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary, Veena Das writes that her main interest in her book is not in describing “the moments of horror, but rather in describing what happens to the subject and the world when the memory of such events is folded into ongoing relationships.” Like Das, my own interest lies in the aftermath of destruction, in the violence that takes place in everyday urban life and in the impact of this violence on communities whose lives have been reshaped by the horrors of war.

I therefore ask: What does it mean to lose one’s home? What does it mean to be uprooted from one’s home and from the people you love and cherish? What does it mean to lose something every day? To lose the familiar streets, buildings and squares, to lose your city — even when you lose them, slowly and gradually. What does it mean to walk on the path of life knowing that even the return to the ruins of your city, the chance to say a final goodbye to the ones you lost, the visit to your erased home, is impossible?

J. Douglas Porteous and Sandra E. Smith define domicide as the: “planned, deliberate destruction of home causing suffering to the dwellers.” This destruction tends to reinforce existing socio-spatial struggles of segregation, inequality and oppressions forced upon people who have already been penalized, disadvantaged and excluded.

Domicide puts “home” as a central concept (Latin: domus), and the deliberate destruction of this home through its suffix, “cide.” The suffix “cide” refers not to the death or decline but rather to the deliberate killing, as in suicide or urbicide.

The intentional destruction of home is selective, causing deep suffering to individuals and communities. Yunpeng Zhang who writes about the social suffering and symbolic violence in Shanghai, China notes that what victims of domicide have in common is their unaccountability in social and numeric senses. Some bodies are seen as irrelevant, and in some cases, land has even become more valuable than the people who live on it. Constructing unaccountability takes on several disguises according to Zhang. At best, a paternalistic view is constructed projecting victims of domicide as inferior and that domicide is in their own interest. As a result, domicidal projects are based on the normalization of victims of domicide, portraying their suffering as a sacrifice for the collective good. In the worse case, however, the “othering” processes within communities constructs an image that dehumanizes the victims of domicide or even considers them enemies of the state who need to be defeated, displaced, punished or killed.

Wartime Domicide

In times of war and conflict, people’s homes and their cultural heritage are destroyed not only for “military purposes” or in the name of “the war on terror,” but rather are also demolished, bulldozed and bombed willfully. Scholars and activists have shown how the built environment has been weaponized in Syria. The destruction of people’s homes has been seen as a tool for punishment, displacement and violence against those who oppose the regime or sympathize with the uprising. The leveling of people’s homes did not only mean the eradication of physical buildings and structures, but also meant the eradication of the conditions of possibility and existence for their personal identities.

Through domicide, people have been either killed or forcibly displaced away from the areas which they lived. Their entire way of life has collapsed, causing more suffering to people who have already been marginalized and are struggling. This happened in many towns and cities in Syria where the government erased “informal” areas at the time of conflict. Even now, after years of destruction as in Hama, these ruined neighborhoods have been kept without any development. Destruction of the built environment in Syria is by no means exceptional as this has been the case in many cities throughout history.

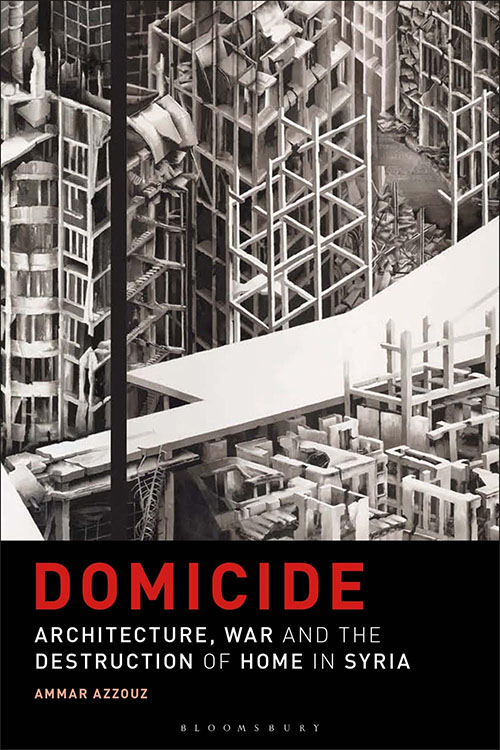

This is an edited excerpt from Domicide: Architecture, War and the Destruction of Home in Syria (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023), by Ammar Azzouz.

Authoritative and incisive. Domicide, unfortunately, has wide-ranging applicability and far-reaching consequences.