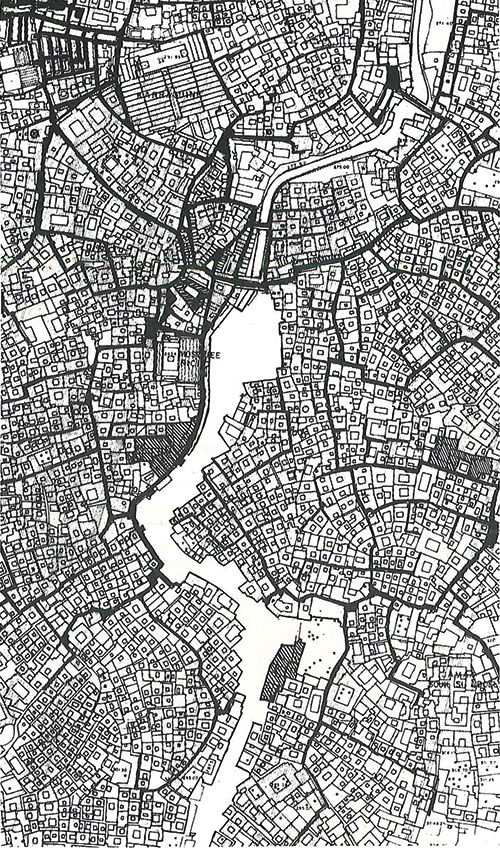

The Roman and Hellenic city was based on the orthogonal grid, known as the gridiron, or chessboard plan. Cities in Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and Libya were built to this model, including Alexandria.

T.H. Shalaby

The atom bomb

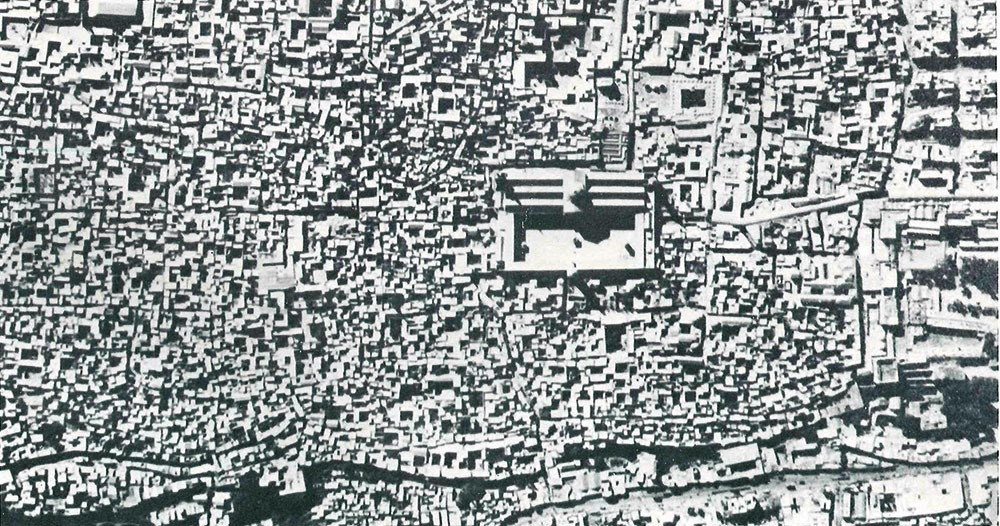

In a 1954 article, Peter Macfarlane wrote that Kuwait looked “as if an atom bomb had struck it” due to the ongoing construction resulting from his company’s new masterplan for the city. Zahra Freeth, the daughter of British political agent Harold Dickson, declared that the Kuwait of her childhood “had been destroyed as effectively, if not as brutally, as by an earthquake.” Saba George Shiber, a Palestinian architect and planner appointed in 1960 as Chief Architect of the Ministry for Public Works in Kuwait, described the new city as shaped by the “onslaught of the car,” and wrote that town planning had spawned “a Pandora’s box of problems.” The architect George Candilis described the urban change as “brutal dislocations in the condition of life.” The American magazine Newsweek referred to Riyadh’s growth in the ‘70s and ‘80s as “the biggest construction site in human history.” This is the time period referred to in Arabic as Al-Tafra, The Leap. It irrevocably changed the society of the Arabian Peninsula in the unfortunate era when rationalism and functionalism reigned dogmatically over the architectural profession. Now the pendulum has swung the other way, and a rising mania of revivalism and nation-branding is spreading across the region.

Culture affects architecture, and architecture in turn affects culture. This may seem like a banal truism to us today, but it was forgotten or actively ignored for much of the 20th century, during the heyday of Modernist planning, when architects and urban planners set forth across the globe armed with arguments of rationality, efficiency, and Scientific Planning that they wielded like fresh converts to a new religion. Perhaps the clearest example of this relationship of culture to urban development, clear archaeological evidence of it, is the transition in the Middle East and North Africa from Roman and Hellenic urbanism to Arab-Islamic urbanism. The Roman and Hellenic city was based on the orthogonal grid, known as the gridiron, or chessboard plan. Cities in Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and Libya were built to this model, including Alexandria. Timgad in Algeria offers an excellent extant example, with its cardo and decumanus crossing at the center mirroring those built by the Romans as far away as Damascus or Chester.

When the Islamic invasion swept over the Mashriq and Maghreb, this system ended abruptly. Wherever Arabs from the Arabian Peninsula settled, their rules of urban settlement, ownership, governance, and dispute resolution prevailed over the Roman and Hellenic models that they had been subjected to in bygone ages. The Arabian invaders instead applied their “khittah” system, first to Basra, Kufa, Fustat, and Qayruwan. Space was first designated for the mosque, then the Dar al-Imara; a souq developed in the open space adjacent to the mosque, and then land was designated to tribal groups and other ethnic groups who were semi-autonomously responsible for their own internal organization. Where existing Roman and Hellenistic cities were occupied, such as in Aleppo and Damascus, the urban form was quickly transformed. The Roman urban model that exuded centralized authority gave way to the anarchic decentralization of the Arabian model. With the arrival of this Arabian tribal model of urban development and the crystallization of Islamic principles of urban governance over the following centuries, the gridiron city would disappear from the Middle East and North Africa until the 20th century when modern urban planners crisscrossed the Arabian Peninsula with their urban grids and eradicated pre-industrial settlements.

Modernism & Destruction

The primary problem of Arabian cities can be boiled down to money and timing. Money: because local rulers found themselves with the means to do what many other governments would certainly do if they had the means to do so. They hired the world’s leading technocratic experts to design and plan modern cities, and there was a palpable sense of doing away with the past and sweeping away what was not modern and new, both with client and technocrat. And timing: because the era of modern masterplanning in the region spanned roughly from 1930 to 1980, a period in which architecture became self-referential, utopian, mired in grand ideological assertions. I have previously written on the staggering extent of western masterplanning in the GCC during this era. A key tenet of Modernism in architecture was the destruction of the past, forcible replacement.

This is exemplified right at the start with the Futurists, who were obsessed with overturning tradition. The Futurist Manifesto of 1909 declared: “We want to glorify war — the only cure for the world,” and called “to destroy museums and libraries.” The co-founder of the movement, Antonio Sant’Elia, exclaimed that ornament in architecture is “absurd” and “supreme imbecility.” Shortly thereafter the 1917 De Stijl manifesto declared that “1. There is an old and a new spirit of the times,” and “2. The War is destroying the old world and its contents.” Corbusier in 1921 referred to this “eliminating process in architecture” as “the vacuum-cleaning period.” He would later call to destroy and rebuild over a dozen cities, such as Paris, Moscow, and Rio de Janeiro. In 1929 the influential Austrian architect Adolf Loos published his essay “Ornament and Crime,” in which he compared the absence of ornament with evolutionary advancement, borrowing Social Darwinist ideas in vogue at the time to argue that societies that ornamented their buildings were culturally backwards. Not a good omen for Arabic-Islamic societies in which maximalism in ornament was common in both religious and vernacular architecture.

What tradition?

…wherever you go in what was once the Roman Empire, you are likely to encounter the same insignia of Roman power. The Romans built the same type of forum, colosseum and public bath whenever they sought to establish a major city, just as under the American imperium, Holiday Inns and shopping malls are ubiquitous. There was little or no desire on the part of the Roman conquerors to heed the genius of place, to incorporate local materials and traditions in their buildings. —Yi-Fu Tuan

Professor Yi-Fu Tuan has argued that tradition is encapsulated by the relationship of constraint and individual action. Constraints caused on a group of people by their climate, culture, and circumstances, where tradition is the question: “Out of all the things that have been handed down to us and that we now possess, what do we wish to pass on?” Societies wish to pass on what they value, and what they value is often pinned on an idea of a Golden Age or “the immemorial ways of one’s ancestors.”

In modern GCC society, the way in which the pre-oil era is viewed is often tinged with nostalgia, and false claims of continuity and purity tarnished by globalism and immigrants. In my professional career, I was once asked by a government official to identify the pure form of arch belonging to a particular region of Arabia. On another occasion, we were asked to avoid incorporating any architectural elements from a particular country that had lost political favor. We referred to these projects as “Identity Projects.”

The question rings repeatedly: what is our true heritage? We do not want theirs. Every province wants to have a pure aesthetic lineage. As one government official put it: “we influenced others, we were not influenced.” Architects are all too happy to pretend fixed borders existed for thousands of years between modern nationalities and provincial identities, cherry-picking architectural features from historic images and extant buildings as examples of a pure, true tradition and then magnifying that to the status of national symbol. The Modernist instinct to destroy images of the past has cut off traditional practice so thoroughly that it is unclear anymore what exactly the traditional forms were. Yi-Fu Tuan and Janet Abu-Lughod argued that buildings are not as important as the skills and crafts to reproduce them. However, the character areas that one might find in Fes or parts of Old Cairo based on industry and crafts such as pottery or leather tanning have largely been removed in the GCC.

Transmission of traditional process in Indian, and Japan

In a 2013 paper, Harpreet Mand discussed the debates that raged around style and self-representation as part of decolonization that took place in India and Japan. At the peak of westernization during the Meiji period in Japan, the debate around tradition and modernity became how to modernize while retaining Japanese traditions and continuity. It rode on a rising wave of nationalism and the overt assertion of Japanese identity, culminating in the “Imperial crown style” of architecture. This parallels a similar trend in Saudi Arabia today with the new “Salmani Architecture Style” promoted heavily by the government in an era of architectural revivalism and anti-expat vitriol. In India, the question was viewed from the point of view of decolonization, national unity, and the desire to symbolize the beginning of a new era after the period of British domination, which extended to architecture and urbanism. The imperial British architect Sir Herbert Baker illustrates the existential problems faced by Indians while discussing the construction of New Delhi, stating that “it is unthinkable that we should throw away all the lessons taught us by the finest architecture in the world and allow the new capitol [sic] of our great Indian Empire to be handed over to modern master builders or architects of India, or the combined efforts of a race of native craftsmen, however genuine and vital their tradition may be.”

Would the designers of Doha, Dubai, Riyadh, Kuwait, Dhahran, disagree with this sentiment?

In both India and Japan, the modern professional architectural bodies were developed under British influence: the Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ) in 1886 and the Indian Institute of Architects (IIA) in 1929. British architect Josiah Conder acted as both head of the AIJ and a professor at the Imperial College of Engineering, run by Japan’s Ministry of Public Works. He had been recruited directly by the government to train Japan’s first generation of modern architects. There is a fundamental difference, however, in how the architectural profession developed in Japan and India. In Japan, the new architects and engineers usurped the position of the traditional “daiku” master carpenters, but the daiku carpentry guilds were able to survive by reconstituting themselves as construction companies, ensuring the retention and transmission of skills, codes, and techniques. These construction companies work symbiotically, collaboratively with Japanese architects, which helped form a uniquely Japanese style — a synthesis of modern technology with Japanese traditions and customs. And although the first generation of Japanese architects were western-trained, they quickly took over government commissions from western architects.

In India, meanwhile, the traditional “sthapathi” master builders were relegated to mere laborers, subordinate to the British architects. This continued through to the post-colonial era in the British-established Public Works Department, resulting in an abrupt break from the past. In the Arab world, and particularly the Arabian Peninsula, the transmission of skills was abbreviated by The Leap. There was no collaborative practice of traditional builders and artisans among the bevy of British and American masterplanners and architects. A total loss of cultural transmission. The Japanese architects had been able to absorb and digest rapid technological changes on their own terms. A perfect illustration of this loss of transmission is the extinction of the courtyard house, a form of house that has existed in the Middle East and North Africa from the neolithic period to WW2, from ancient Egypt and Babylonia up until the 20th century. Along with the compound-house form, it was the dominant house type in the Arabian Peninsula. The masterplans and design codes did not allow this indigenous house form to exist. It was replaced by the detached villa for locals and the apartment building for expats. A silent extinction of a multi-millenarian way of living.

Identity Anxiety

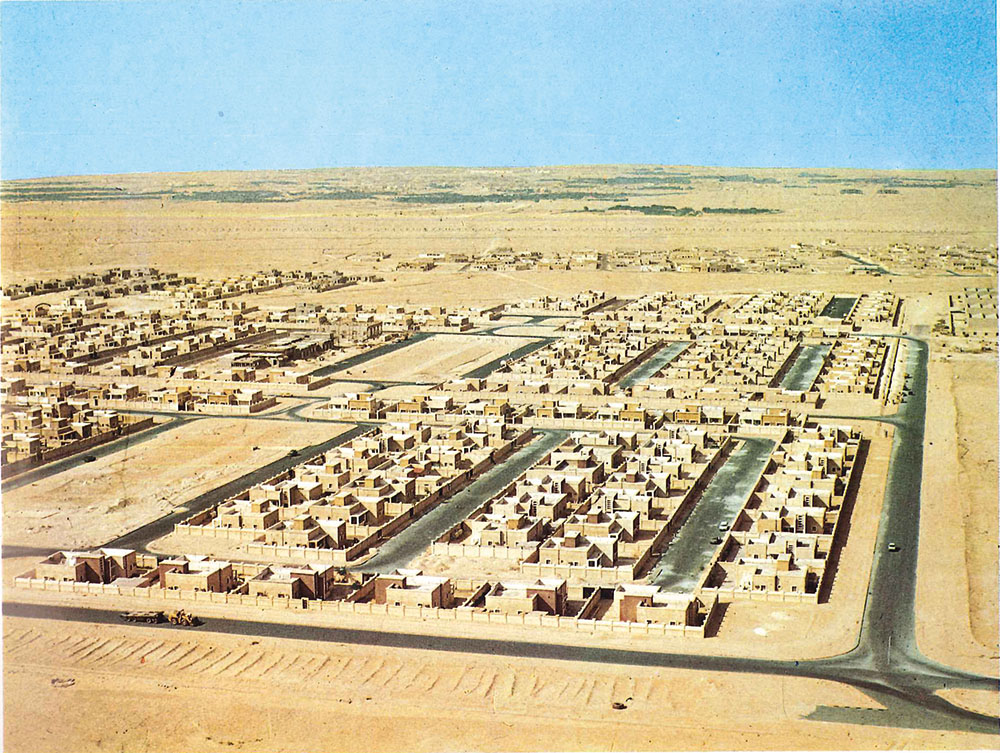

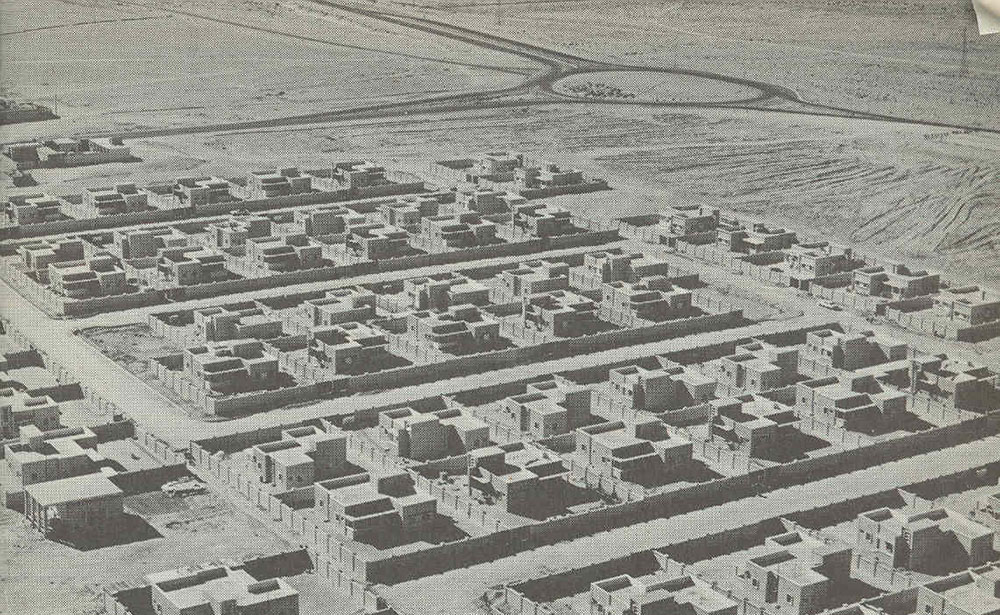

The impact of Corbusier and CIAM on a generation of planners, and these values of rationalism, functionalism, and a disdain for the past and of cultural specificity are clearly evident in the masterplans and architectural projects of this era in the Arabian Peninsula. The masterplanner of Riyadh, Constantinos Doxiadis, coined a new term for his ideology of planning: Ekistics. His philosophy of practice was a marriage of ancient Greco-Roman gridiron planning with the Modernist ideas of functionalism and rational order. His Action Area Plans for the central region of Saudi Arabia would exhibit the same gridiron system. The cities of Ras Tanura, Abuqaiq, Dammam, and Khobar, that were masterplanned by Aramco, helped to establish the gridiron pattern as the primary form of urban development in Saudi Arabia. It may be this relentless sameness of modern GCC cities, the palpable break with the pre-oil urban traditions, the way in which they were planned, transcendent over any local conditions, that has created this anxiety around identity today. That has pushed governments and architectural critics and influencers to demand a revival, a Neo-Arabian-Traditionalism. Unfortunately, it is all too often simplistic, pastiche, lipstick treatment of facades with an impoverished understanding of urbanism and design guidelines.

In Qatar, new major projects must be submitted to the PEO (Private Engineering Office) for review. It has become a quasi-municipal planning entity, simultaneously a design review board and also a private subsidiary of the Emiri Diwan. However, new buildings such as the Ministry of Interior are a perfect example of this strained revivalist effort. The previous Ministry of Interior building, designed in the 70s by Lebanese architect William Sednaoui, is a complex climate-responsive design exhibiting the best that Critical Regionalism could offer. The new building is a Postmodern structure that feels at least 40 years too late. In its structure — its ocean of surface parking, its deep setbacks, paved lawns, roundabouts, entry portico — it is a typical modern structure. But to make it Qatari, there are crenellations and turrets. It typifies the architect’s instinct, seen in architectural competitions in the region for decades, of designing a building as you would anywhere in the world, and then applying a lipstick treatment of stick-on crenellations and Arabic text and calling it local.

True traditional revival requires a complete revolution in planning, in transport, in design guidelines. No amount of crenellations or wind towers can fundamentally change these cities that have been planned to a completely different set of values. With no living traditions to pass on, all we can do is pass on crenellations, or abstracted forms of traditional life such as the sail, dhow, or sand dune.

Cultural breakages

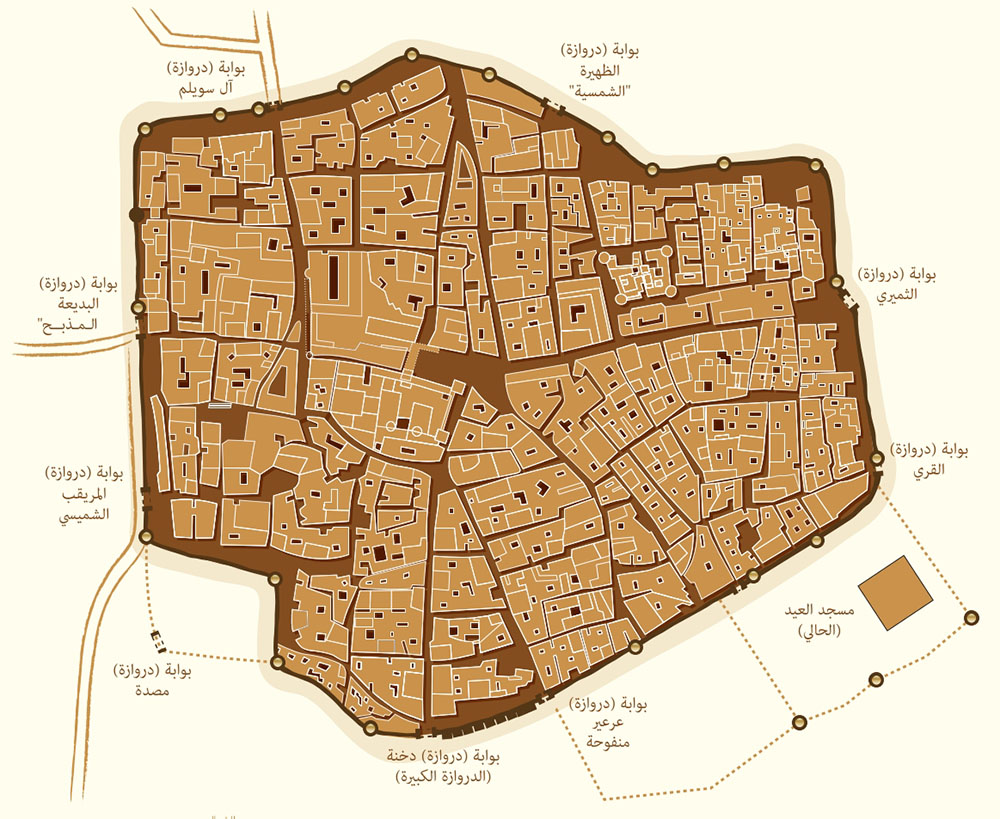

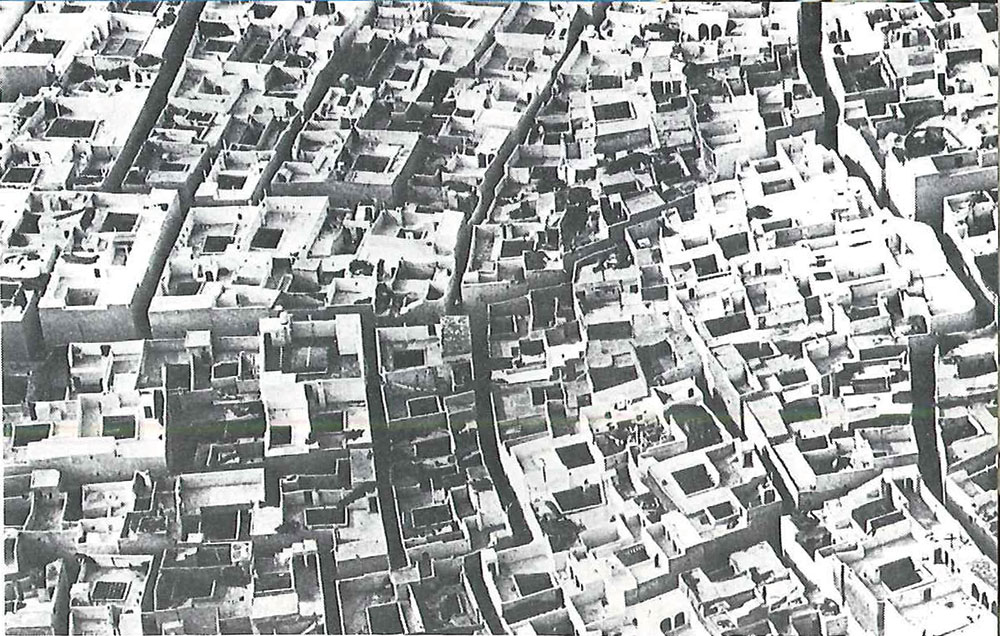

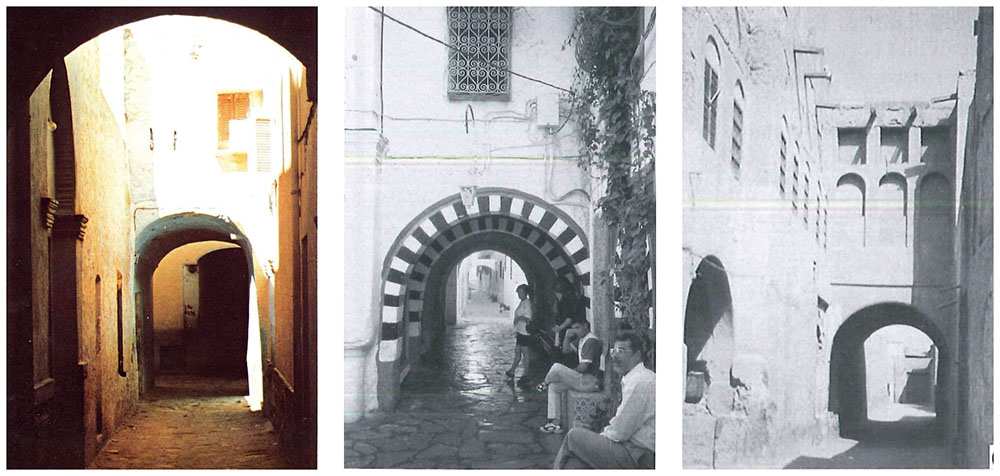

The genesis, evolution & growth of Arab-Islamic cities in the pre-modern period prior to the adoption of civil codes is covered extensively by authors such as Besim Hakim, Jamel Akbar, Saleh al-Hathloul, Nezar Alsayyad and others. From the importance of the waqf and Iqta’ systems, to dispute resolution, inheritance and plot division; from the role of the muhtasib and “Ahkam al-Souq,” to specific codes of practice mentioned by jurists such as Ibn Hanbal, Ibn Wansharīsi, Ibn al-Qadim, Ibn Habīb, Ibn ar-Rāmi, and many others. Title deeds did not exist, and ownership was based on possession. These practices resulted in a traditional Arab-Islamic urban form identified by individually walled and gated quarters with narrow meandering routes and cul-de-sacs that provided street-level shade. Houses were built around courtyards, with projecting jetties to increase street-level shade and “sabat” overpasses spanning across the streets. Roofs were occupied both as social spaces and connected as a route, and geometric latticework was used in wood and steel to enhance privacy while providing a porous ventilating tissue to facades. The traditional neighborhood unit was referred to in eastern Arabia as a “fereej.” As Todd Reisz explains in his history of Dubai, the traditional fereej was relational, based on kinship, solar gain, and wind capture. These neighborhoods were often clan-based, with groups of relatives (a “hamola”) clustering near one another, where the norm was for multi-generational extended families to occupy the same home.

By introducing the gridiron urban layout as the predominant form of modern urban development, the detached villa as the predominant form of housing, the ring road or orbital motorway as the primary distributional mechanism, and the coastal motorway as the main structuring element of the city’s relationship to the sea, the planner neuters thousands of years of cultural accretion. The extended family house becomes a nuclear family villa. Private walkable neighborhoods become car-dominated pedestrian-free dead zones. Coastal seafaring cultures such as in Kuwait and Qatar change from their seaward orientation to an inward orientation cut off from the sea by a major highway. Each government in the GCC exacerbated the problems of Modernist sprawl through their housing allocation policies. In Qatar, all locals were guaranteed housing through the 1964 “Popular Housing Scheme.” In Kuwait during the first Minoprio masterplan, families were moved from the city-center to the new neighborhoods, and recently sedentarized Bedouins were housed using the Plot and Loan Scheme. Similar schemes in Saudi Arabia, such as ARAMCO’s Land Subdivision Plan and its 1951 Resettlement Scheme, and the UAE’s ‘national housing’ policy have helped to create a globally unique urban phenomenon where the detached villa is the main housing form for locals and where the government is trapped in a feedback loop of ever-continuous sprawl.

Architects have tended to treat tradition as a catalogue of elements. You can design any modern building to be traditional by throwing a few traditional elements on it, even if its plot and setbacks and road widths are all modern — like a man who drives to his office job and wears a suit getting a tribal tattoo. But it is the cultural impacts of planning that are more important: territoriality, a sense of public ownership and belonging, social interaction, local control. In her analysis of how modern masterplanning affected Kuwaiti culture and politics, Farah Al-Nakib notes that 19th and 20th century European explorers and sailors who visited Kuwait prior to the oil boom unanimously commented on its cleanliness. Each neighborhood was responsible for its own cleanliness.

What of Arab cities today? Is there a high sense of public ownership of the street, or of local responsibility? In a 1982 study on how culture affects territoriality, experimenters placed bags of garbage in the front yards and pavements in US and Greek neighborhoods. They found that in the US local homeowners cleaned away the trash bags in an average of six hours, whilst in Greece it was 15 hours. In another study from 1981, researchers analyzed Slavic and non-Slavic households in a community in Kansas City, with both studies arguing that public cleanliness was a function of culture and that some cultures are just cleaner. However, in the same period, the urban designer Donald Appleyard ran his own studies that focused on urbanism, finding that street and neighborhood design affected the number of friends that residents reported having, the number of social visits between neighbors, and found that high traffic streets reduced the time residents spent outdoors as well as their sense of ‘personal territory’ and personal responsibility over areas outside their own homes. Urban design, therefore, directly affects the social characteristics of communities.

Many studies have looked at “norm emergence” in neighborhoods and “acquaintance formation,” at how “group-level expression” within neighborhoods enhances bonds between residents, and even carried out “rumor-transmission analysis” by looking at how streetblock design affected the spread of rumors. It is clear that the design and layout of entryways, routes, cross-paths, and pavements in neighborhoods affects the social existence of residents to a great degree. The Saudi author Mashary Al-Naim has argued that each fereej and clan sought to differentiate itself from the others. This would perhaps be what the researchers liked to call “group-level expression.”

Arab culture emphasizes communal gatherings, and the traditional city was filled with pocket spaces. There was a range of privacy levels that no longer exists. In the detached villa model of urbanism, once you exit your front door you are in a public space. You enter your car and go to another public space. In the traditional city of cul-de-sacs, gated entryways, and clustered familial groups, there were layered zones of semi-privacy before one was truly outside in the public. Several authors have noted the social retreat of women into the home in the post-oil suburbs of several parts of the Arabian Peninsula. Without an economic imperative to take part in outdoor labor, nor communal spaces that could nurture an outdoor social life, women’s territorial expanse was reduced to the home. Al-Nakib notes how in the pre-oil town of Kuwait, women were active participants in outdoor life, particularly when the men were out at sea, often selling snacks in the “baraha” yards between neighborhoods. Men often sat outside their homes on “dach’a” benches, and children spent their time in local open areas. The Arab city was the city of closure & enclosure, the baraha, fina’, sāhah.

Sir Anthony Minoprio, whose partner Peter McFarlane had described Kuwait 30 years earlier as if an atom bomb had struck it, reflected on the masterplan in his retirement: “It was a difficult commission,” he said. “We didn’t know anything much about the Muslim world and the Kuwaitis wanted a city — they wanted a new city…. All we could give them was what we knew.” What Arabs received was a design philosophy that represented the European zeitgeist and Anglo-American social traditions. If modern cities want to assert their identities but cannot grasp building and artistic traditions that have been lost, perhaps they should look towards the social conditions of the past that they want to recreate through urban design. Would it be more valuable to pass on traditions of enclosure, privacy, cleanliness, territorial belonging, or would they rather reproduce crenellations and symbols of sails?