Based in Lubbock, Texas, Lahib Jaddo has enjoyed a transnational and extensive career in the world of art. Since the early 1990s, her visual works have been displayed in solo and group exhibitions, including eight open and juried shows in 2022 alone, in destinations from California to Amman, Jordan, and multiple points in between. Championed in the state she calls home, Jaddo’s work is held in numerous collections throughout Texas, and in private and public collections throughout North America and beyond. Jaddo’s illustrated myths and narratives give grounding and purpose to the myriad moving parts of a life that transcends borders. Viewing her art conjures up notions of an invisible maternal hand making Ikebana. Jaddo’s artwork seems to depict an ongoing arrangement and rearrangement of cultures, ethnicities, and stories, and perhaps reclamation of a primeval family tree, too.

Beginning with architectural studies at the American University of Beirut (AUB), Jaddo dove deeper into the discipline at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, New York, and Texas Tech University, Lubbock. Adding to her repertoire a second master’s degree in fine arts from Texas Tech, Jaddo landed appointments as professor and later dean in the College of Architecture at her Texas alma mater, where she still teaches today. As a sought-after artist, her work is showcased in national and international exhibitions, curated around themes such as freedom, migration, human and women’s rights, and climate and social justice.

When it comes to Iraq, Jaddo recalls a family that flourished the years before the Baath party seized power. Her parents were cornerstones of their Turkmen community and contributed to the founding of modern Iraq. In 1965, however, Jaddo’s family was uprooted and, ever since, has had an on-again, off-again relationship with Iraq.

On the eve of the 20th anniversary of the March 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, TMR talked with Jaddo about her Turkmen background, her experiences in Iraq, and her life today.

The Turkmen ethnic group is one of the largest ethnicities in Iraq and thought to have origins in 7th century Central Asia. Geographically dispersed, at least in part by the Ottoman Empire, the Turkmen people live primarily across a slanted swath of Iraq, extending approximately from the country’s northwestern corner to its mid-southeastern border. Speakers of a Turkish dialect, under Saddam Hussein’s regime the Turkmen people were denied linguistic, cultural, and political rights.

Mischa Geracoulis: What was early life in Iraq like for your family?

Lahib Jaddo: My father’s career as an irrigation engineer began around 1945, and concentrated on projects to control the flooding of the Tigris River. His work also included building roads, airports, and utility systems in Baghdad. Educated and forward-thinking, he wanted to marry an educated Turkmen woman. My mother had similar aspirations, broke with tradition, and decided against marrying a cousin. Through the Iraqi Turkmen network, my parents found each other and married in 1954. My mother was a schoolteacher, and later a principal. After devoting years to rearing us five kids, she changed careers. In the mid-1980s, she traveled to Japan to learn Ikebana, the ancient Japanese art of flower-arranging. When she returned to Iraq, she shifted her teaching to the subjects of plants, flowers, and the art of arrangement.

TMR: When did you and your family first leave Iraq?

JADDO: The first time we left was in 1965, with the arrival of the Baath Party and their orders to hang my father. After a 10-year stay in Beirut, which is where I went to high school and to AUB for one year of architecture study, civil war broke out in Lebanon. In 1975, we were granted amnesty and our family returned to Iraq. Shortly thereafter, however, I moved to New York to continue my education. As the eldest of five children, I was the first to leave, and the rest of us gradually scattered.

My sister, Parine, a filmmaker now, left in 1976 for Ohio State University. My brother, Falah, returned with my parents to Iraq, completed high school, served in the army, and then in the 1980s ran away from the Iraq-Iran war to complete his education at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. My sister, Yanar, who runs an organization for women’s freedom in Iraq, started her education in architecture in Baghdad before going to Toronto to complete a degree in Women’s Studies in 2010. And my brother, Ibrahim, the youngest, born in 1962, left Iraq in 1980 and got his degree in computer programming in Buffalo, New York.

Later, Desert Storm really changed everything. After Iraq attacked Kuwait in 1990, the United States defended Kuwait, a major supplier of oil to the U.S. Fraught with war, Iraq became a difficult place in which to live, so my parents left for Canada.

TMR: What took you to Texas?

JADDO: The move to Texas was to study architecture and fine art at Texas Tech University. West Texas eventually became my home. It’s where I married and raised my kids, and where my studio is based.

TMR: How would you describe your work as an artist?

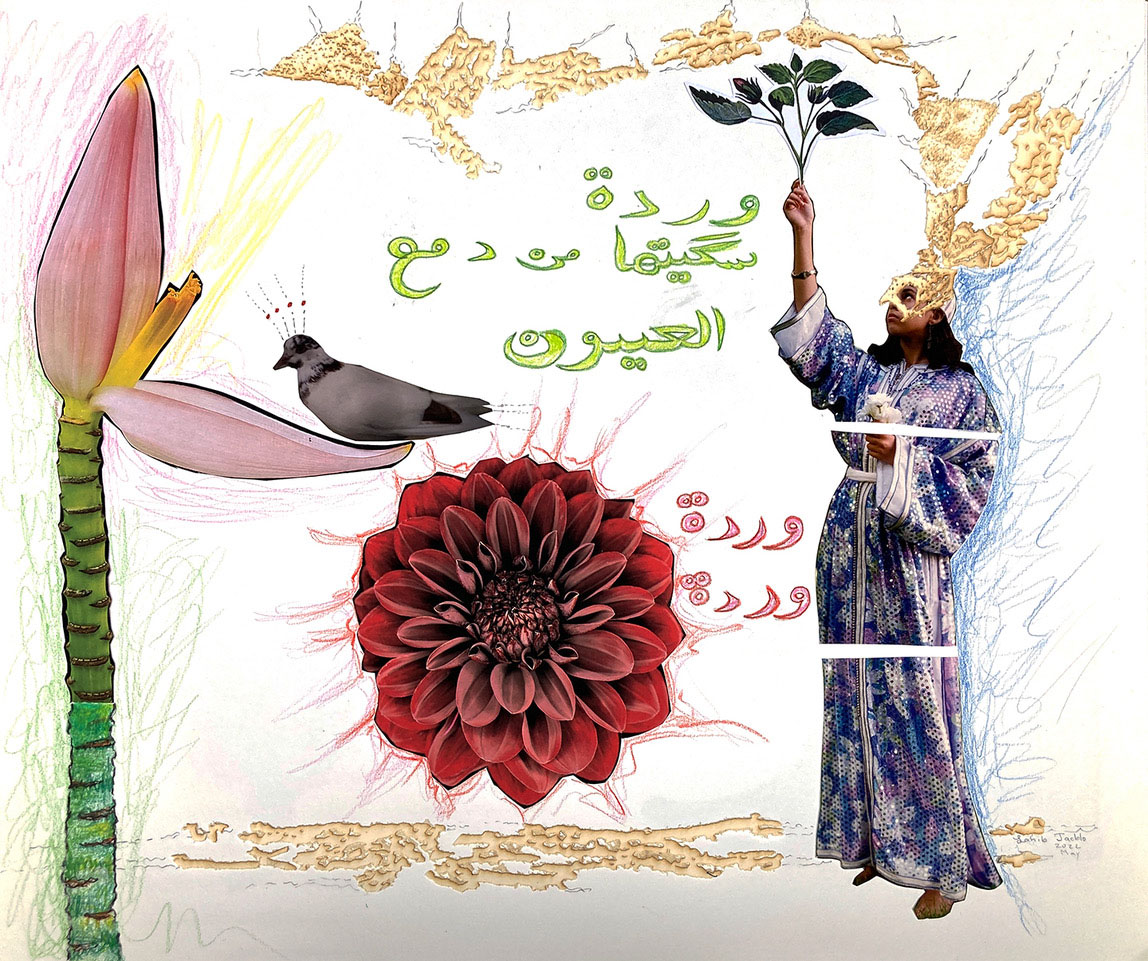

JADDO: My work is about myths, imaginary narratives that connect me firmly to the realm of nature and spirit. I create visual narratives to help me feel connected and centered in this world. Over the years, my work has received attention, and I continue to show my work locally, regionally, nationally, and globally.

TMR: Would you say more about your Turkmen heritage?

JADDO: My paternal grandfather, Haji Mohammad Jaddo, is from Tel Afar, a small town in northwest Iraq. He is from a Turkmen tribe that had settled in the area during the Abbasid Dynasty (750 CE to 1258 CE). I did some research and discovered that the tribe was placed in that area in a diagonal layout, stretching across Iraq from the northwest region down to the southeast, to separate the Arabs from the Kurdish or Persian or whatever other ethnicity was present then in Iraq’s northeast. Another search uncovered that my paternal grandfather’s tribe had been (presumably hired) horsemen and fighters for the Abbasids!

JADDO: My paternal grandfather, Haji Mohammad Jaddo, is from Tel Afar, a small town in northwest Iraq. He is from a Turkmen tribe that had settled in the area during the Abbasid Dynasty (750 CE to 1258 CE). I did some research and discovered that the tribe was placed in that area in a diagonal layout, stretching across Iraq from the northwest region down to the southeast, to separate the Arabs from the Kurdish or Persian or whatever other ethnicity was present then in Iraq’s northeast. Another search uncovered that my paternal grandfather’s tribe had been (presumably hired) horsemen and fighters for the Abbasids!

In about 1910, Haji Mohammad Jaddo was unhappily forced into a first marriage with an older relative. Later, on one of his trips through northwestern Syria, while visiting several Shammar tribal groups to trade wheat for cattle, he stopped at a water well to quench his thirst. There he met Mariam, who turned out to be the head Shammar tribe’s adopted daughter. Mariam was Armenian, and had lost all her family during the Armenian Genocide. As the story goes, my grandfather purchased her with some gold coins, and she became his beloved second wife in or around 1920.

TMR: We’re on the eve of the 20th anniversary of the second Gulf War, also called the Iraq War, that began when the U.S. invaded Iraq on the 20th of March, 2003. Do you think the country is finally coming out from under the cloud of war and occupation, and beginning to stand on its own authority?

JADDO: I am at a distance from Iraq. My conclusions are based on what I hear and see from the people I know who are living there, or somehow connected to Iraq through their work.

The country is lost. Parts of it are a complete mess due to ISIS destruction. I’ve heard that my father’s hometown, Tel Afar, is still hurting, and so are many Yezidi towns in that area. National laws have relaxed, now allowing multiple marriages for men, which is wreaking havoc in communities and probably triggering more disturbances than I am aware of. Is all of this because of the Gulf War? I only know that the Gulf War during 1990-1991 removed all sense of order that had been in place, and many of the secular organizations were replaced with religious control.

TMR: What is your relationship with Iraq now, and when were you last there?

JADDO: My connection to Iraq has been strengthened more recently through Facebook. In 2022, an Iraq-based Turkmen Facebook group connected with me, and now promotes me as one of their people in diaspora. But the last time I went to Iraq was 10 years earlier, in 2012, with my daughter, filmmaker Nadia Shihab, to help with her film, Amal’s Garden (2012). The film is about my Turkmen aunt and uncle who refused to leave their homestead in Kirkuk, which was also my mother’s hometown.

[Nadia Shihab’s feature-length documentary, Jaddoland (2018), is a poignant exploration of the inner and outer landscapes of Lahib Jaddo — cherished mother, woman, and artist. Jaddoland conveys introspection and emotional longing that could be said to emanate from the filmmaker as much as from her subject. Communicated in the film too are innovation, resiliency, and a sense of renewal inherent in the processes of creation and immigration.]

TMR: Do you think that artists are now able to thrive in Iraq?

JADDO: I am not sure how to answer this, as I’ve not shown my work in Iraq since 2005.

TMR: Do you have hope for the future of Iraq?

JADDO: Hope, in my mind, resides in education. After the Gulf War, an embargo was imposed, creating many problems that led to a lack of education for the younger generations. Iraq had a very strong educational system before then. Why should quality education not be possible in Iraq, considering how much the country generates from oil sales? Where is all that income going? If the country manages to strengthen the education of younger generations, then there is hope.

* “Poppies for Kirkuk” includes a Kirkuki poem that reads:

Ekin Ektim olmadi

Bulbul gule konmadi

Kalaya olan zulüm

Hıç kımseye olmadı

Translation:

I planted fields

Nothing grew

Birds had no roses to perch on

This torture that befell our Citadel

No one had seen the like before

Jaddo’s upcoming exhibits are updated on her Instagram and Facebook pages.

Lahib, thank you for including me in your distribution. I enjoyed reading the interview and seeing the artwork, getting a better sense of your history and that of your family and the geography of that history. I especially like “Four Nadias” and “Poppies for Kirkuk” that came from your heart.

Thanks Jim, Four Nadias city scape I photographed in the destroyed Citadel of Kirkuk in 2004 when I was finally able to go back to the city. The destruction was heart wrenching. Memory becomes alive with how one remembers a place that was thriving with life. Four Nadias sit like ghosts from an era gone forever.

Thanks very much for reading and commenting, Jim!