In the aftermath of his father’s death by shrapnel from an Iraqi shell, Dilan Qadir contends with a life intricately shaped by his absence.

Dilan Qadir

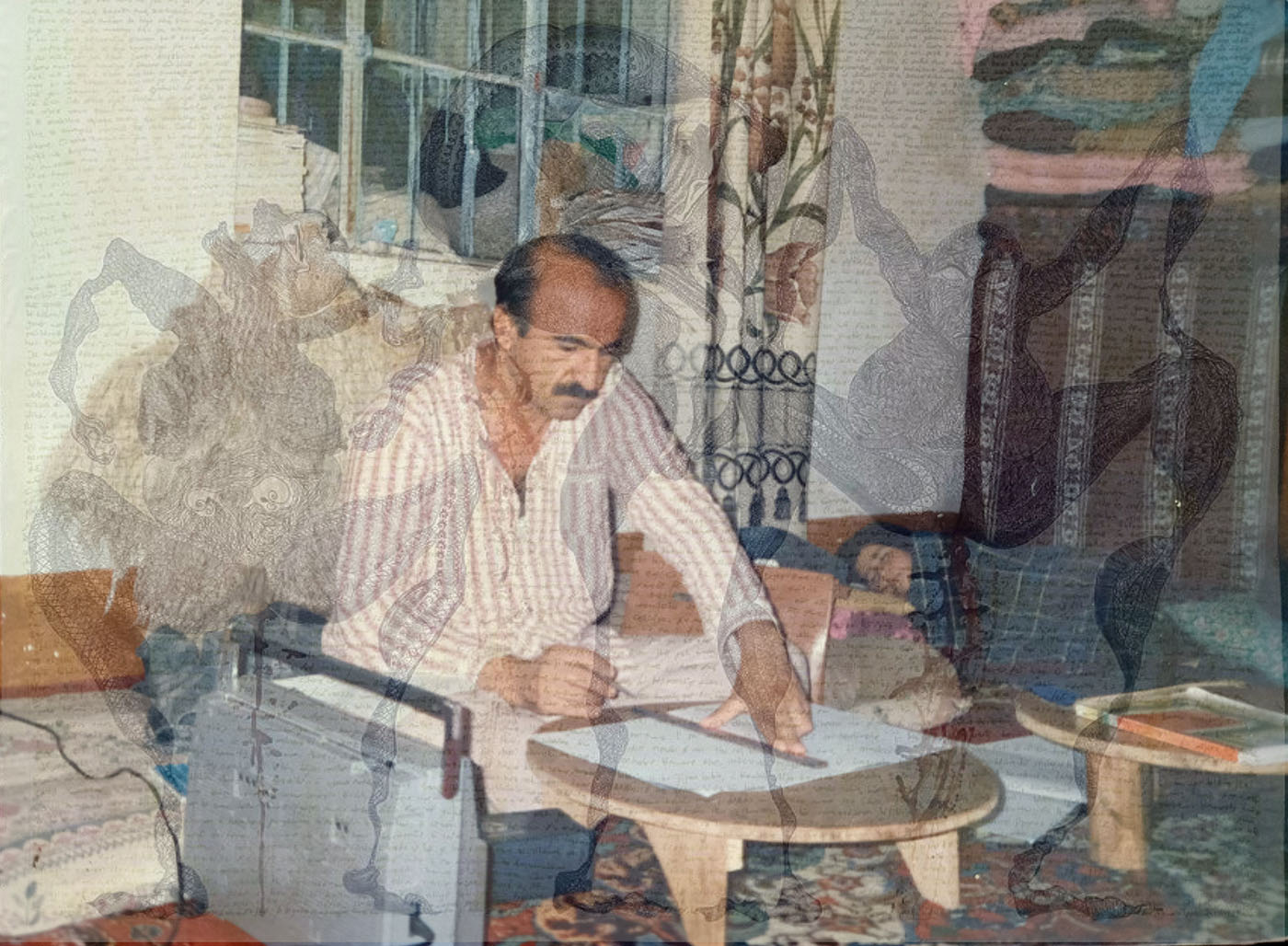

When my 40-year-old father had his lunch on October 7, 1991, he didn’t know it was going to be his last meal. I was almost four years old at the time, and I remember my father wearing a white shirt and a navy blue kurdish vest and sharwal — baggy trousers — with a large black sash tied around his waist. In my memory, he is squatting beside a single burner portable stove in the cemented front yard, and he scoops out fried potatoes from a pan and rolls them in flatbread to make quick, small wraps that he eats with sliced tomatoes and onions. Although my father has just returned from the secondary school where he worked as a principal and also taught the Kurdish language, and although he is hungry and is in a rush and the air is charged with urgency, he seems composed and focused on his lunch, as if what he is going to do next will go as smoothly as a well-planned classroom lesson.

My mother is in the front yard, baking flatbread on a convex metal griddle. My paternal grandmother is there too, and she is restless.

“Please don’t go out now, Kaka,” my grandmother implores my father. She addresses him with the affectionate honorific Kaka, the way his five sons and three daughters do. “Wait until the fighting is over.”

My father eats in silence. An AKM with a folding double-strut stock dangles from his shoulder, and a set of magazines in green specter gear encircles his waist. Outside, gunfire is exchanged between Kurdish peshmerga fighters and Iraqi army troops, and every now and then the troops fire mortar shells that explode in our small town, Arbat, in the Kurdistan region. The Iraqi army is pushing to regain areas that were liberated by the Kurds earlier in the spring uprising, and the Kurdish minority, having tasted freedom from prosecution by the Ba’ath regime, is resisting.

As my father finishes his lunch and prepares to go out, my 16-year-old eldest sister asks him: “Can I come with you, Kaka?”

“No, my daughter,” my father answers. “Do you think I’m going on a shopping trip to the bazaar?”

My father leaves to check on the disorder, to be of help in his usual selfless way, and to look for my eldest brother who is somewhere outside. I imagine my six-foot tall father peeking behind corners and ducking to avoid being hit. I imagine him advising the locals he sees to stay indoors. I imagine him asking the residents if they had seen my eldest brother.

Then the unexpected happens that changes the course of events. My father encounters several Iraqi soldiers who have refused to fight and have surrendered to the Kurdish forces.

“What should we do with them?” a Kurdish fighter who leads the soldiers asks my father.

“We’re not going to kill them, of course,” my father replies. “Let’s take them somewhere safe.”

My father and an acquaintance of his bring the surrendered soldiers to the local mosque so they can rest and wait out the fighting. The mosque, however, having been washed earlier that day, is locked. My father sends for the keys to be fetched, and while waiting, he sends someone home to bring the leftovers from his lunch. He then takes the soldiers to a nearby bakery to feed them. People start to gather around the soldiers. Iraqi forces positioned at an observation post pick up on the gathering, and, perhaps considering it a preparation for an attack, they fire a shell. A single shell with immaculate precision.

Back home, my mother is still cooking when the shell explodes outside. My mother, who doesn’t get hit, faints. My grandmother rushes to her, splashes water onto her face, and my mother comes to. My mother, who has been married to my father for 20 years, doesn’t understand why she has fainted, but she feels something terrible has just happened. Shortly after, the main door bursts open and a neighbor races in.

“Come with me,” she urges my grandmother and my mother.

My grandmother doesn’t ask for any explanation and bolts outside.

“Is everyone okay?” my mother asks the neighbor.

“Yes,” she answers.

“Is Hussein okay?” my mother asks about my father.

“Yes,” the neighbor says. “Just come with me.”

My mother goes with the neighbor, and my nine-year-old youngest sister accompanies them.

By the time they reach the mosque, which has been unlocked, the bodies of my father, another resident, and two Iraqi soldiers lie motionless. The intestines of the soldiers are strewn on the floor. My father is lying on his back. His stomach and his chest have been hit with multiple shrapnel. Most of them are small. The biggest shrapnel, however, is the one closest to his heart, where his warm blood visibly stains his white shirt under his navy blue vest.

After my father’s death, one of my family’s regular visitors when I was growing up was a distant relative. She was an old lady with trembling hands, and she constantly wore a black scarf and a black maxi. Aunt Hapsa usually visited us around noon, and my mother would invite her to join us for lunch. My mother, my siblings, and I would sit cross-legged on a carpet around a nylon tablecloth laid on the floor.

“Please have a bite with us, Aunt Hapsa,” my mother would say.

But Aunt Hapsa wouldn’t budge.

“No, thank you,” she would say. “I’m not hungry.”

My mother would insist that she must join us or else we would not eat.

“Don’t worry about me,” Aunt Hapsa would say. “Enjoy your meal. Dilan is still a child.”

I don’t know what Aunt Hapsa meant to imply by saying I was still a child.

“Oh, no,” my mother would say, “he is all grown up now.” She would then start to eat, and I would join her, aware of Aunt Hapsa’s presence and loving gaze.

Aunt Hapsa was one of the many guests who refused to eat our food. It would take me some time to understand that it was because my father was dead and I was considered an orphan. For as long as I was under 18, some guests avoided my family’s food. They did so because they wanted to sympathize with my fatherlessness. With this tradition, which originated from a cultural belief, they sought to lessen the burden of my father’s death. But contrary to their good intentions, their abstention sharpened the absence of my father. Each time such a guest visited us and refused to eat or drink, I was reminded that I was an orphan, I would feel a sense of unease, and I would lament my father’s death.

That I was a child made things worse, for one of the plights of childhood is a sense of being stuck with unfortunate situations. Back then, it was my conviction that my orphanhood was unending, and I couldn’t conceive of what the release from that condition looked like. And the more I continued to grow up and step out into the world on my own, the more I was reminded of my father’s martyrdom.

When I was 14 years old, my family moved into a new neighborhood and I had to change schools. One day in August, I went to the local secondary school and filled out a form in the reception area. After waiting for ten minutes, I was allowed to see the principal. He was a middle-aged man sitting behind a large desk. He skimmed over my application with an agitated look, put down the paper, and looked at me over the rims of his eyeglasses.

“I’m sorry, son,” he said, “but we don’t have space. You should try another school.”

I stood frozen in the office. I must have glimpsed what my life would look like without being enrolled in school, and I must have felt terror. My life revolved around being a student, and there was nothing else for me to do. In the face of the principal’s rejection, I felt weak and helpless.

A few seconds passed in silence. When our gazes met and neither of us said anything, it felt awkward.

“But this is the only school in the neighborhood,” I finally said.

“Well,” the principal said, “it is full.”

I didn’t move.

“Tell me,” he said with a softened tone. “What does your father do?”

“He is a martyr.”

Suddenly, a solemn look took over his face. He straightened his posture, grabbed a pen, and signed my application.

“Because your father is a martyr,” he said as he handed me the paper, “there is no need for further delay and I welcome you to the school.”

As I left and went to a bus stop, I felt my father walking beside me. He boarded the bus with me and sat next to me. No one else could see him. I then thought about my school admission, getting in by the skin of my teeth, and how my father had reached back from death and played a role in my life. His death was not for nothing, I thought to myself. I missed him and my eyes teared up in silence.

Each time I think of my father, the first image that comes to my mind is his grave. I grew up visiting his grave several times each year, on the anniversary of his martyrdom — on the first days of the Feast of Ramadan and the Feast of Sacrifice.

During a family visit to the cemetery one Friday morning in late 2000s, the view was the same. I could roughly count 100 white and gray concrete headstones. The terrain was mostly dirt, except for some pine trees and bushes. My mother, one of my sisters, one of my sisters-in-law, my six-year-old niece and I entered the cemetery and walked toward my father’s grave. My niece, Rava, maneuvered playfully among the tombstones like a soccer player crossing a field with a ball. The wind played with her curly hair as she moved ahead of us. She then stopped, looked back, and seemed lost.

“Where is father Hussein?” she asked. She addressed the grave by the name of her grandfather.

“Come over here,” I told her. I held Rava’s hand and led her toward the grave at the upper part of the cemetery. We gathered around a rectangular, grayish blue tombstone made of marble that was distinctively different from the others. We took turns and kissed the headstone. None of us adults asked Rava to do so. We thought with time she would come to follow my family’s tradition.

Although the practice of kissing the headstone baffled me, I related it to my family’s need to connect with my father. In a way, my father’s headstone and grave strengthened his memory.

My mother moved the pebbles on the grave. One pebble at a time, she moved them as if she was moving the beads of a rosary. She murmured a prayer only she understood.

My sister’s eyes became moist, and she sniffed.

My sister-in-law stood in silence and watched Rava as she romped around and played with fallen pine cones.

The sun warmed my face, and I wondered how warm or cool it must be down in the grave beneath one and a half meters of soil. For a second, I imagined my father’s body shrouded in white linen cloth, placed on his back, looking up at us. The image evaporated and was replaced by the concept of my father as a living presence. I then quietly reported to my father where I was at in my life.

If the past is still alive in our present, it is not in its entirety, but in its bits and pieces. My siblings and I have slightly different memories of the exact details of my father’s last meal and the day in general. While I remember him squatting in the courtyard to eat, my youngest sister says he was seated on the veranda. And while my siblings remember the shots fired and the explosions, my memory of that day holds no sound, it is like a silent movie in my mind. Regardless of such differences, two certainties remain: my father’s last meal and his subsequent death.

I still wonder if his death was made less painful because of his last meal. The practice of providing a last meal to prisoners who are about to be executed dates back to the Greeks, where it was likely done so that the soul of the dead pass the river Styx peacefully and their hungry ghosts would not return to earth. But a more feasible explanation as to why it is humane to feed people who are about to die may lie in the fact that eating makes us feel content, and we are more likely to face our demise with less agitation.

What is known is that my father spent his last moments in a calm that is sometimes characteristic of people who come to accept their death.

“My time has come,” my father reportedly said to a neighbor who witnessed his last breaths.

“This is enough, this is enough” my father then repeatedly said. Was he referring to the fighting between the Kurds and the Iraqi regime? To his journey on earth? No one knows.

My father wrote poems, contemplated studying a master’s degree, and from what I had been told, considered immigrating to Europe. His death has come to make me think of people as fragmentary beings who strive to put together a complete picture of themselves and their lives. But it sometimes happens that in the process of applying brushstrokes, death enters and our pictures remain forever unfinished. That’s one reason enough why no one should be killed. Everyone is born with the right to have a chance to work on the paintings that define their life for as long as possible.