Kaya Genç on the arduous journey of translator Kawa Nemir.

Co-publishing with The Dial (Paris)

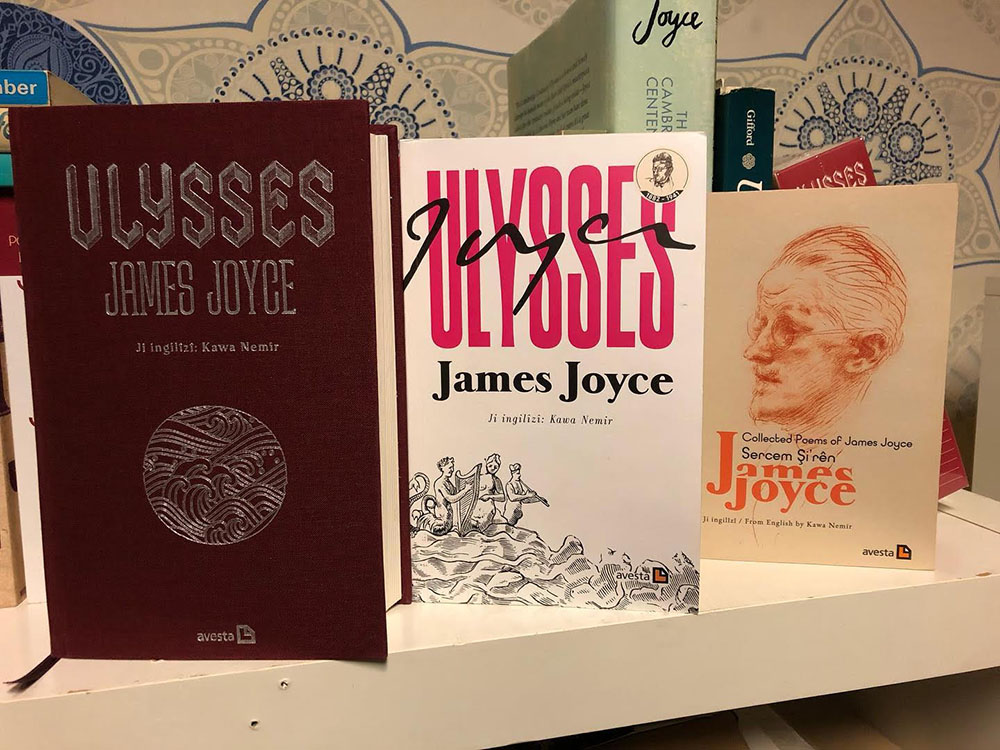

Ulysses, a novel by James Joyce

Translated to Kurdish by Kawa Nemir

Avesta 2023

ISBN: 9786258383416

Kaya Genç

On June 15, 2012, at the age of 38, Kawa Nemir visited his family home in Istanbul, lay on his childhood bed and began translating the following sentence into his native tongue: “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed.” The next afternoon, Nemir took the notebook with him, flew to Diyarbakır in eastern Turkey and continued translating the rest of James Joyce’s Ulysses into Kurdish. It did not escape his attention that it was June 16, Bloomsday, the day during which Ulysses, set in 1904, takes place.

Nemir, a chain-smoking poet with intense eyes and a romantic bent, had spent a decade translating Shakespeare’s sonnets into Kurdish. In Turkey — and increasingly in Europe, where many Kurds live in diaspora — bookworms have grown up on his translations of Emily Dickinson, Sara Teasdale and Walt Whitman.

For Nemir, translating Ulysses into Kurdish was a way to draw attention to a language that had been the victim of nationalist politics in Turkey. Kurdish, thought to be spoken by between 40 and 60 million people, is a West Iranian language from the Indo-Iranian language family. Inside Turkey, where the teaching of Turkish as a first language is mandatory, Kurdish faces a number of problems. Students at public schools can take Kurdish only as an elective, and there is a shortage of Kurdish language instructors because the government refuses to hire and appoint teachers who speak Kurdish at public schools. If, despite all these problems, a translator from Turkey who learned his native tongue on his own could translate Ulysses into Kurdish, this would set an example for aspiring Kurdish writers and translators. It would also show Turks the breadth and wealth of the language that some of them had dismissed and belittled over the past century.

The elder son of an affluent Kurdish family, Nemir was born in 1974. His own linguistic history mirrored that of many of his generation: While he spoke Kurdish at home, his school lessons were in Turkish and English. By the time he became a teenager, Nemir had forgotten Kurdish. Between 1990 and 1992, while studying at a high school in Istanbul, he devoted his time to regaining his Kurdish by studying the language each day. He decided to stop writing in Turkish, except for works of criticism.

Nemir took to working in Kurdish instead. After graduating from college with a degree in English literature, he found work at Jiyana Rewşen, a Kurdish literary magazine, in 1997 and became its chief editor, encouraging contributors and readers to open their eyes to world literature and become more cosmopolitan. In the meantime, he began to translate works by Shakespeare and William Blake into Kurdish.

The Kurdish artist and author Şener Özmen, a good friend of Nemir’s, said that Nemir’s translations of English classics, particularly his renditions of Shakespeare’s sonnets, gave Özmen himself the confidence to write in Kurdish. “I used to write in Turkish but switched to Kurdish, partly thanks to [Nemir’s] passion for languages,” he said. “Very few people wrote in Kurdish in Diyarbakır, where I lived.” Most Kurds didn’t in fact know the grammar, syntax and vocabulary of Kurdish well enough to write in it, and chose to articulate the Kurdish experience in Turkish-language essays, poems and books instead. Nemir’s work sought to change that. As an editor, he published Özmen’s novella Rojnivîska Spinoza (Spinoza’s diary) alongside a Kurdish translation of William Blake’s poem “The Tyger.” This was an era of growing interest in, and partial political relaxation for, the Kurdish language. In 2009, the government lifted the ban on Kurdish television and radio broadcasting (Kurdish private broadcasting had been banned for decades). A Kurdish channel of the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT), the public broadcaster, launched that same year. In 2011, Mardin Artuklu University began offering a Kurdish literature major to undergraduates — a first in the history of Turkey. A year later, Kurdish entered the school curriculum as an elective. “Kurdish books became easier to reach,” Özmen said. “We could go to a bookstore and see which new Kurdish titles were there. And the most exciting new voice was Kawa Nemir.”

In the poems from his first collection, 2003’s Selpakfiroş (Handkerchief seller), Nemir plays with the anxiety of influence that comes from encountering such a range of authors. “Wild parsley – you don’t know – has left its hue on the language,” he writes in “After the Rain” (translated by Patrick Lewis):

on the outskirts of the city the bogs bellow gently as water

the radiant, alluring, wide-eyed reeds recite.

Nemir encountered Ulysses in high school English class. As he gained more experience as a translator and poet, he felt very strongly that this could be the text whose translation would reveal the extensive vocabulary and elaborate syntax of the Kurdish language, which had been subjected to centuries of assimilation.

To translate Ulysses into a language that few Turks could learn, Nemir thought, would silence those who mocked Kurds by saying they didn’t even have a language. According to the Turkish state’s official history, after all, Kurds were simply Turkish mountain people whose name arose from the “kart-kürt” sound their boots made while walking in the snow. Nemir felt that Ulysses was the text that gave English literature its prestige, with its structural, aesthetic and literary complexity. Nemir figured that if he could replicate Joyce’s linguistic feat in Kurdish, with all its grammatical and historical texture, then nobody would be able to dismiss it as an inferior language.

Ulysses begins early in the morning on June 16, 1904, at the top of a Martello tower along the water in Dublin, where the 22-year-old Stephen Dedalus is staying with the medical student Buck Mulligan. In translating the opening chapter into Kurdish, Nemir picked the word Til to describe the Martello tower. For Nemir, the defensive forts of Ireland resembled watchtowers, or “Tils,” in Mesopotamia — similar to those he saw in Diyarbakır, where many Kurdish citizens of Turkey live. He spent time in Birca Şems, one of the local towers, climbing to its top many times at the crack of dawn, when no one was around, to read and write. The Dublin Bay reminded him of the Tigris River and its valley.

Nemir felt he had been preparing to undertake this translation his whole life, having filled dozens of notebooks with Kurdish words and expressions in his 20s. He kept Ferhenga Biwêjan a mezin (The Grand Dictionary), a dictionary of Kurdish idioms collected by the writer Dîlawer Zeraq, by his side. Zeraq had spent 20 years preparing this 2,000-page work, which contains 18,000 entries of idioms in Kurmanji, the most widely spoken form of Kurdish, which is often written in Latin script. But it was Nemir’s own notebooks, filled with Kurdish idioms he overheard in conversation, that helped him the most.

A notebook he kept during his 1998 visit to Şırnak, a village with rivers and forests, featured names of numerous freshwater creatures that later appeared in his translation of Ulysses. In other sections of the novel, he struggled with matching Joyce’s large vocabulary about the sea. After all, Nemir noted, Kurdistan is one of the most mountainous regions in the world, and Kurds never expanded far from the mountains. For the translator, the problem was finding Kurdish words for sea creatures that Kurdish writers had not mentioned in their works — and that thereby remained unnamed in the Kurdish language. He studied various genera of fish, trying to locate words used in Kurdish texts, turning to his notebooks. In 1994, Nemir had scribbled the word “whale-path” in a notebook while studying Beowulf in college. He knew that Kurds called whales neheng, so he wrote in his notebook: “whale-path: rêka nehengan.”

Kurdish poet Ehmedê Xanî’s 17th-century epic Mem û Zîn, a mystical romance about two star-crossed lovers, was among Nemir’s main sources. He extracted names of ships from it: Xanî describes zenberîs, small vessels, sailing from Diyarbakır to the Persian Gulf. That came in handy when Nemir was working on “Cyclops,” the 12th chapter of Ulysses. If he couldn’t find anything in Kurdish sources or his notebooks, Nemir coined words himself, basing them in Latin and Greek.

Sometimes, he modeled his syntax off of Kurdish poetry. To translate “Oxen of the Sun,” the 14th chapter of Ulysses, which takes place in a maternity hospital during the birth of a son and surveils the beginnings and development of the English language, he drew upon Kurdish classical literature, and transposed the verse into the chapter’s prose. Translating the chapter took him four years, as he pondered individual words for many months.

Another notebook was just a dictionary of words Nemir had gathered from conversations with Kurdish convicts, words describing details about drinking alcohol, playing card games and having sex. For example, bûye pilot, an expression Nemir had heard from a convict while staying at a prison in Mardin, describes “someone ready for action in all hours of the day.” But the word, which has a double meaning, can suggest both courage and drink. When describing Bob Doran, a character who suffers from a bad marriage in Ulysses and attempts to escape it through an extravagant alcoholic binge, he wrote, “Hê di sa‘et pênca da bûye pilot”: “Boozed at five o’clock.”

More than 30 of Nemir’s notebooks comprised words he learned from his mother, who had a deep sense of the Kurdish language. “I used all of those in Ulysses,” he said. Among the words, proverbs, expressions and idioms his mother dictated to him were cagarê lihêfê (“quilt”), ‘ilmê sînemdeftera (“lore”) and zimanê maran li ber min qetand (“by your kind solicitations”). “I didn’t know any of these words he used, and they were all Kurdish,” Özmen recalled. Nemir said he considered those words, idioms, proverbs, metaphors and slang terms as “saved from death because they found their place in Ulysses.”

Fifteen million Kurds live in Turkey, but many Turks are unaware of the Kurdish language’s deep historic roots and richness. Before 2002, Turkish authorities refused to acknowledge Kurdish as a distinct language spoken within Turkey’s borders. Their policy was rooted in the Turkish nationalist project of forging a culturally and linguistically homogeneous nation. After the foundation of the republic in 1923, Turkish became the only official language, and this policy expanded to the ban of Kurdish names (names containing the letters X, W, Q, Î, Û and Ê, which are not considered part of the Turkish language, were banned between 1928 and 2013) and a resettlement of populations aimed at weakening the demographic dominance of Kurmanji.

Some bans were relaxed in the 2000s and the early 2010s, as part of the Turkish government’s “Kurdish opening,” and more Turks, not just Kurds, began to learn Kurdish. But in the last few years, after the government’s democratic initiative on Kurdish rights came to a close, there have been growing tensions around Kurdish politics in Turkey. Meanwhile, despite growing interest in Kurdish, learning the language inside Turkey’s borders is not a universal demand among Kurdish families. In 2019, a Kurdish research center in Diyarbakır conducted a survey of 600 Kurds between the ages of 18 and 30 in southern Turkey. Forty-four percent said they could speak their mother tongue, and only 18 percent said they could read and write it as well. When nine Kurdish parties established a “Kurdish language platform” in 2018 to promote the use of Kurdish, they found that in numerous municipalities held by the pro-Kurdish HDP party, Kurdish-language signs had been taken down by government appointees. For Kurdish activists and intellectuals, this was further proof that the assault on their language remained unwavering.

In translating Ulysses into a language that, as he put it, “miraculously survived the hellish conditions of the Middle East for one thousand years,” Nemir had one advantage: Kurdish, he found, is very close to Old English, as the syntaxes of Kurdish and English are quite similar. In Kurdish, which belongs to the same eastern branch of the Indo-European language group as English, the sentence order consists of the subject, the verb and the object, which is very similar to that of English. The linguists Robinson Paulmony and Shivan Mawlood Hussein point to how “in English as well as Kurdish languages, simple, perfect and progressive aspects are distinguished.” The sentence order is largely the same, so it’s easier to create rhyming.

From 2012 to 2015, Nemir finished half of his translation of Ulysses in Diyarbakır. But in 2014, months into this work, a chain of geopolitical events intervened in his life and the lives of his fellow Kurds. Across the Syrian border, the Islamic State group undertook genocidal acts against Syria’s Kurdish-speaking Yazidi communities, exiling and executing men and forcing women and girls into sexual slavery. As its militants enslaved, tortured and executed Yazidis, the Islamic State group was finalizing its advance on the Kurdish town of Kobanî in northern Syria. By September 2014, with 200,000 Syrians seeking refuge in Turkey, Kurdish volunteers from Turkey demanded to cross the border to defend Kobanî. But the Turkish state didn’t allow their passage and refused to intervene in the city’s defense. This led to pro-Kobanî demonstrations across Turkey. Protests in Mardin, Van, Bingöl and Diyarbakır resulted in curfews. By Oct. 8, 2014, 19 people had died in Kurdish demonstrations, and a week later, the death toll reached 31: at least one protester died by police fire; killers of some found shot on the streets couldn’t be identified. In November, 15,000 Kurds marched in Diyarbakır, where Nemir was increasingly derailed from his Ulysses translation.

The first barricades for the Kobanî protests were erected outside Nemir’s apartment. Between focused bouts of translation, he would witness violent clashes on the street below his study’s window and watch others on social media. After finishing a chapter, he would spend the night watching the aerial bombing of nearby cities Nusaybin and Cizre.

But staying in Diyarbakır became too dangerous. In mid-2015, Nemir decided to resettle in Mardin, a city farther south, thinking that it would be calmer. He formed a group of proofreaders, mostly Kurdish literature students from the Mardin Artuklu University. Because each member came from a different background, they all brought new words to Joyce’s text, calling the elders of their families in Hakkari, Van and Adıyaman to excavate words and then notifying Nemir of their findings.

While looking at the translation of “Scylla and Charybdis,” the ninth chapter of Ulysses, for example, the group tried to come up with the meaning of the word “jobber,” Joyce’s word for a black marketeer. One participant located the Kurdish equivalent, malgir, in a phrase they encountered in the city of Hakkari, named after the Kurdish tribe Hakkar. There was also the Kurdish word for “diver” — during a conversation in Mardin, Nemir learned that it meant xozneber in Kurdish, a word used by elders during the 1980s.

Nemir spent 2015 and 2016 revising his Ulysses with their input. His linguist friend Ergin Opengin, from the American University of Kurdistan, devoted hours to the project. Nemir’s friend Özmen, meanwhile, worked on the designs of the paperback and hardcover editions of the book, and tried to keep up the translator’s spirits by bringing him various copies of Ulysses from London, Brussels, New York and Paris.

Nemir spent 2015 and 2016 revising his Ulysses with their input. His linguist friend Ergin Opengin, from the American University of Kurdistan, devoted hours to the project. Nemir’s friend Özmen, meanwhile, worked on the designs of the paperback and hardcover editions of the book, and tried to keep up the translator’s spirits by bringing him various copies of Ulysses from London, Brussels, New York and Paris.

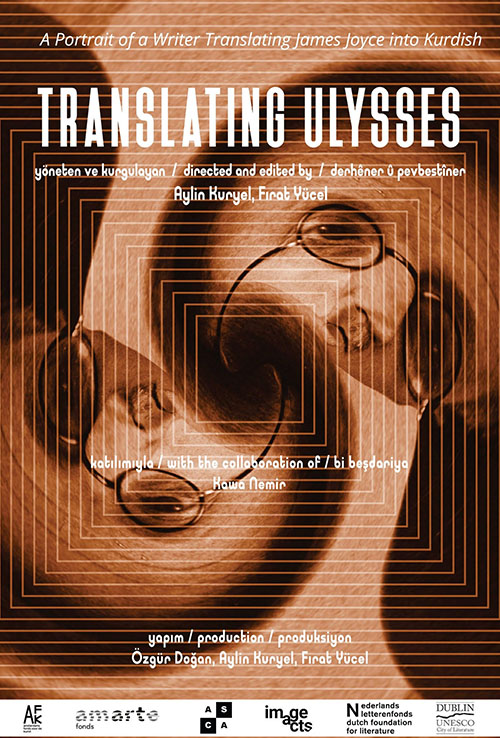

Toward the end of 2017, Nemir saw that his activist, artist and journalist friends were leaving Turkey. On March 1, 2018, he went to the airport, taking a handbag, a coat, underwear, a pair of trousers, his Ulysses notebooks and the Gabler edition of Ulysses. He took a KLM flight to Amsterdam, leaving behind the Joyce archive he had collected for 27 years in Turkey, and arrived at Schiphol Airport at 10 p.m. The Dutch Foundation for Literature had accepted Nemir as a resident in the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. Around this time, Nemir met Aylin Kuryel and Fırat Yücel, a couple from Turkey who would later direct Translating Ulysses, a documentary about Nemir. Their film weaves the proofreading process of Ulysses into Nemir’s struggle to find an apartment during the housing crisis in Amsterdam. In Turkey, the International Istanbul Film Festival refused to screen Translating Ulysses, which features footage of the violent suppression of the 2014 Kobanî protests. Kuryel, the filmmaker, jokingly described Translating Ulysses as a “censored documentary about the translation of a book censored for its obscenity into a language that remains banned a century later.”

Nemir is most interested in what Kurdish authors will make of his translation. Özlem Belçim Galip, a scholar of Kurdish literature at the University of Oxford, said she believes Nemir is “one of the translators who see the Kurdish language as an ocean of flexibility and creativity where there is no limit.” According to Özmen, the Kurdish Ulysses marks a “starting point for all Kurdish writers, novelists and short story writers.”

With its rich history of poetry and prose, Kurdish literature presents a great many styles and themes for today’s writers, and the Kurdish Ulysses, published on March 21, 2023, the day on which Kurds celebrated the arrival of new year as part of Newroz festivities, is a starting point for more experimental literary endeavors in contemporary Kurdish fiction. Nemir’s translation shows how expansive the Kurdish vocabulary is and how experimental contemporary Kurdish authors can write novels and poems in their language. The translation will remind them of the deep grammatical reserves of Kurdish, and many may feel inspired to produce texts that embrace a great poetic tradition while articulating present-day realities.

Nowadays, in his apartment in Amsterdam, Nemir is writing a 900-page Kurdish readers’ guide to Ulysses, with references, photographs and a 200-page preface. As for his next translation, he said, he’s hard at work on “something even bigger” than Ulysses: Finnegans Wake.