It was as if I knew by instinct — as only children do — what life would teach me as an adult: that when the tragic meets the absurd, the most pernicious form of oppression is the denial of common sense.

Asmaa Elgamal

I don’t know when or why I fell in love with Egyptian black-and-white cinema. Maybe it was the thrill of watching the Egypt of my parents’ youth come to life: dazzling starlets dancing the twist in full swing skirts; college boys walking to class in oversized suits; wide, empty roads that bore no resemblance to the maze of humans and cars that was my hometown of Alexandria. Or maybe it was the possibility that every scene could turn into a song, rolling off the tongues of passengers on a train, embracing the melody of ten fingers and a bowtie on a single grand piano, bursting into a fully choreographed performance in the middle of the street.

In the handful of childhood years I spent with my parents in the Gulf, those films were my lifeline to home. I loved the eccentric characters and whimsical plotlines. I loved the familiarity of hearing my mother tongue. And I loved the “lightness of blood” we Egyptians were so well-known for, that good-humored ability to turn anything and everything into a joke.

A regular feature on the Egyptian satellite channel was the 1959 classic Serr Ta’eyet El-Ekhfaa, “The Secret of the Invisibility Cap.” The film follows ‘Asfour — literally, “bird” — as he stumbles across a magic cap and uses its powers to exact revenge on his bully and archrival, Amin. An atypical hero, ‘Asfour is affable if not handsome, meek yet principled, and an all-around good guy. His bully, on the other hand, is a Neanderthal of a man who not only enjoys tormenting ‘Asfour for his own amusement, but also threatens to steal his girlfriend and force her into marriage.

I was amused by the idea of a cap that made you invisible, especially if used to prank your unsuspecting bullies. Yet even with ‘Asfour’s endless comedic antics, the film was never one of my favorites. Egyptian black-and-white cinema was stocked with its fair share of the most evil of villains — almost any role played by Mahmoud El-Meligy or Zaki Rostom was a strong contender — but there was something about Amin that made me especially uneasy, and the entire film uncomfortable to watch. Even now, I can recall in vivid detail the thick walrus moustache that lay beneath his nose and the firm grip with which he grabs ‘Asfour by the collar and pins him to the wall. I recall his steady gaze as he reaches into his side pocket, pulls out a small ring box, and utters one of the most iconic lines in Egyptian cinema:

“El ‘elba dy feeha eh?”

What’s in the box? It’s a simple question, but ‘Asfour doesn’t have the answer.

With every high-pitched squeak of “I don’t know!” Amin whips out a hand and slaps the terrified ‘Asfour across the face. Every slap is followed by the exaggerated kat-ish of a mis-timed crackle, the delay lending an almost comic quality to the scene. Then, with an eerie calmness, Amin leans in and declares, “El ‘elba dy…feeha feel!”

It still strikes me that in spite of his terror, the bird-like ‘Asfour chooses to reject the absurdity of Amin’s declaration: no, he says, there is no way this tiny box could contain an elephant. But as his tormentor’s grip tightens and his voice booms louder, he finally surrenders his common sense: Feeha feel! He squeals. “It’s an elephant! Feeha feel!”

As a child, I knew well enough that slap-stick humor and onomatopoeic soundtracks were meant to be funny. But I still shriveled at the sight of ‘Asfour’s body pinned to the wall and the squeaky sound of his defeat. It wasn’t fear, exactly: there was no pool of blood, no dark alleyway, no ominous music. Yet, there was a sinister quality to the scene, one which I couldn’t quite identify. It was as if I knew by instinct — as only children do — what life would teach me as an adult: that when the tragic meets the absurd, the most pernicious form of oppression is the denial of common sense.

In February 2011, I asked my mother to save the papers.

“All the papers!” I repeated, clutching the phone to my ear as my voice climbed a decibel or two at the last words.

It was as if I was chasing the airwaves that separated me from my family, from Egypt, from the fireworks and euphoria of Cairo’s Tahrir Square. As if my voice could compensate for my absence from the heart of it all, and for the poor alternative that was this form of communication.

It had been eighteen days. Eighteen days of tears, of heated arguments, of grief, of despair, of inspiration, and of hope. Eighteen days that blended into seventeen sleepless nights spent refreshing my Twitter feed every hour for any news from home — the home that was thousands of miles from the London apartment I shared with two roommates, all of us master’s students, all of us with a piece of us left behind in Egypt.

Only television could take us back.

January 25. National Police Day. I gawk at the crowds on the screen, gathered in Tahrir Square, the downtown roundabout where I had spent the bulk of my college years. Behind the chanting voices, I imagine, is the memory of Khaled Saeed, the 28-year-old man who had been killed at the hands of police not too far from my childhood home in Alexandria.

Photos of his mangled face — beaten, bruised, disfigured — are all over social media. Police reports insist he suffocated while swallowing a packet of hash.

There’s an elephant in the box.

January 28. The Day of Rage. A battle line is drawn across the Nile. Protestors stand on the Qasr El-Nil bridge, guarded on either end by the commanding posture of its four bronze lion statues. They march towards Tahrir Square, pushing against columns of riot police, braving the rubber bullets, breathing through white clouds of smoke and tear gas. When the air vibrates with the call of the adhan, worshippers stand side-by-side, bowing and kneeling in prayer as if immune to the deluge of water being fired at them from a cannon standing just outside the frame.

I feel like a prisoner behind the screen.

February 1. Volunteers clean streets and distribute food. Tens of thousands are still packed in and around Tahrir Square, wearing buckets and cooking pots for helmets. The mood is festive: fingers strum on a guitar, faces beam with pride, and voices burst into collective song.

It’s a scene right out of an Egyptian black-and-white classic.

February 2. Men gallop into the square on horses and camels, faces full of rage, hands armed with clubs, batons and machetes. Clubs beat into the crowds, protesters part like the Red Sea, hopes are crushed along with bones.

These aren’t hired thugs, we are told.

There’s an elephant in the box.

February 11. Tahrir Square is exploding with fireworks, their sparks dancing along with thousands of flags flapping in the night sky. The following day, the papers will read, Al-sha’b asqat al-nitham: “The people have toppled the regime.”

And there I was, an agonizing distance away, with a phone clutched to my ear, wanting desperately to be part of the crowd. But if I couldn’t smell the faint whiff of gunpowder in the smoky air, or hear the symphony of car horns competing with cries of jubilation, or dig my heels into the uneven pavements, I was determined to hold tomorrow’s papers in my hands. Somehow, running my fingers across the headlines would prove that I too, was part of this moment. Somehow, it would forever make it mine.

So I asked my mother to save the daily papers.

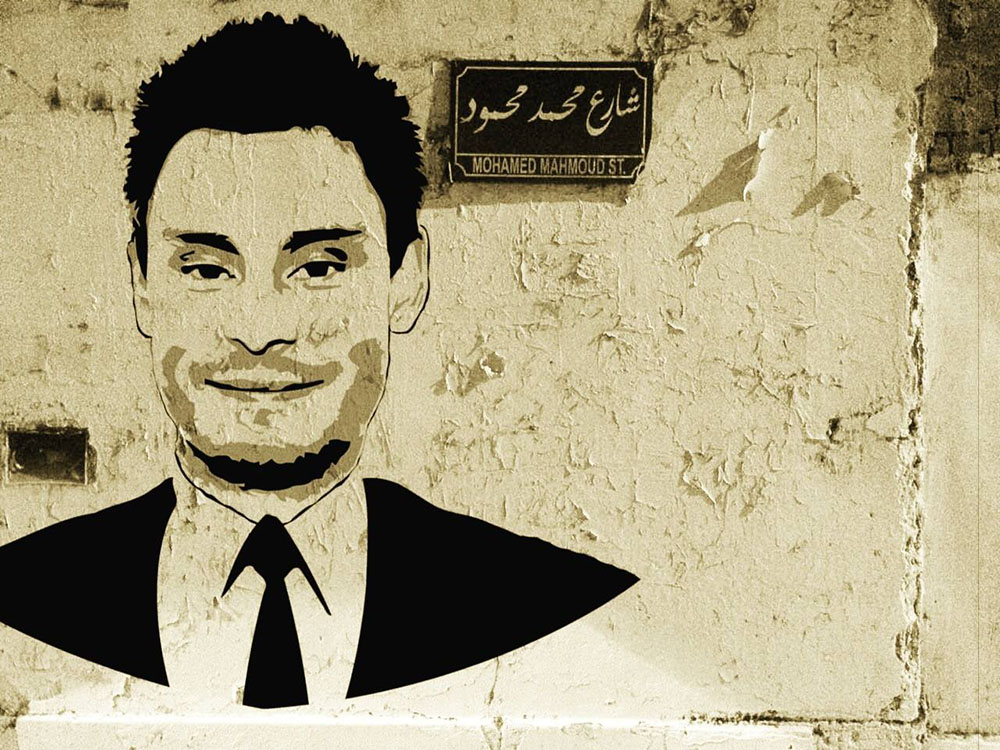

I first saw Giulio on TV. He had gentle eyes, a short trimmed beard, and spikes of soft, dark chocolate hair leaning over his forehead. Peeking from underneath his olive green sweater was a salmon-toned shirt collar. And across his photo the headline read, “Search continues for missing University of Cambridge student.”

He had been missing since January 25, 2016, the fifth anniversary of the Egyptian Revolution. Uprising? Events? I no longer knew what to call it.

This year, there were no marches, no chants thundering from one balcony to the next, no flags flying over Tahrir Square. There were only arrests, lots of them. My stack of saved newspapers — about a kilogram’s worth — was collecting dust on the top shelf of my bedroom closet.

Giulio, I learned, was an Italian researcher studying independent trade unions in Egypt. And he was 28 years old, the same age as me. One minute, he was at the metro station on his way to downtown Cairo. The next minute, he was gone.

Ten days later, his face was still on TV, this time because his corpse had been found. His battered body — beaten, burnt, tortured — was found half-naked in a ditch on the side of the Cairo-Alexandria highway. I knew that road. I had driven on that road more times than I could count.

According to police, Giulio had died in a road accident.

I tried to imagine this possible hit-and-run. Maybe Giulio fancied a midnight stroll on the 220-kilometer highway. He was blasting music in his earphones, which was why he couldn’t hear the oncoming car — no, something bigger, a truck — heading in his direction. Yes, a truck would explain his seven broken ribs, his splintered fingers, his shattered toes. Maybe the truck was carrying a shipment of knives. They tumbled out of the back of the truck, ninja-style, and stabbed him all over his body. Yes, on the soles of his feet too — this Giulio liked to walk barefoot. And the cigarette burns on his skin? Maybe he was a smoker, and he…no, maybe the driver was a smoker, and he dumped an ashtray full of burning cigarettes on the battered Giulio before he fled the scene. And the missing clothes? The wind blew them away.

A road accident was plausible.

There’s an elephant in the box.

A few weeks later, it was revealed that Giulio had been under government surveillance. A different headline crawled across the screen: “Gang members involved in murder of Italian student killed in police shootout.” Giulio, the official story went, was abducted by a gang of thugs. Unfortunately, all four gang members had been killed in a police shootout before they could be interrogated. Perhaps if they had lived, they could have reasonably explained why a gang of thieves would torture their victim for days on end. Maybe they would have confessed to being method actors, fully committed to the impersonation of the character of the wayward policeman.

There’s an elephant in the box.

As the litany of theories continued to stumble out of the TV, I turned away from Giulio’s smiling photo to the email open on my laptop screen. It was my letter of admission to a PhD program at the University of Cambridge, the place where I would have almost certainly met him. The place where we might have shared a supervisor, a group of friends, perhaps a meal — in a different life.

Looking at the congratulatory message, I felt neither pride nor accomplishment, but sorrow. Deep, piercing sorrow. Folding the screen, I tucked my laptop under my arm and walked out of the room, the bruising pellets of the TV fading into the distance.

Can you mourn a friendship that never was?

Four years later, I was back in Cairo after a few months spent in Cambridge. Not the Cambridge where I would have met Giulio, but the other Cambridge, in Massachusetts, where I had been working towards my PhD for the last few years. With the aroma of fresh basbousa all around me, I was cuddled under a blanket on my mother’s living room couch, my feet warm and my stomach full of homemade goodness.

But instead of enjoying a quiet family evening over a bite of dessert, I wanted to crawl over to the TV, dig my fingers into the LCD display, and rip out the bottom left corner of the screen.

At first it was hard to make out. Small but ostentatious, it looked like a shock of gold splattered across a dark navy background. I had to squint to read what it said: “Police Day, 68 years.” Adorned by a frame of golden leaves, the Arabic calligraphy sat alongside the head and disproportionately large wing of an eagle. At the top of the frame, like a bow on a Christmas wreath, was a red, white and black ribbon of the Egyptian flag, held at the center by another golden eagle bearing the colors of the flag on its chest. It was gaud meets nationalism, sprinkled with some holiday spirit.

Though January 25 had been National Police Day since 1952, never before had I seen it celebrated in the bottom left corner of every Egyptian TV channel for an entire month. I certainly hadn’t seen it celebrated with such gusto before 2011, nor during the few years that followed. I even remembered a year or two when that little icon at the bottom of the screen was celebrating the January 25 Revolution.

But today, it was celebrating Police Day. Only Police Day. It was as if nine years after an uprising that began in protest of police brutality, we were, by way of omission, choosing to celebrate that same brutality.

And there it was, that gaudy display of selective amnesia, goading me from the bottom left corner of the TV.

It felt like a trap. Like it was fishing for a reaction, daring me to say something controversial, to break the unspoken ceasefire that allows families to coexist in peace in spite of their opposing views. I had been there before: it starts with a protestation, grows into an argument, and ends with a dismissal of the naïve ideals of the “Facebook generation.” I knew it was wiser to say nothing.

For the past ten days or so, I had even succeeded: Instead of protesting the treachery of memory, I tapped my foot in nervous energy. Instead of mourning the disillusionment of a generation, I fired critiques at the half-baked plotlines of the 9 p.m. mosalsal. Instead of facing my wounded sense of belonging, I stuffed my face with dessert.

But there it was again. Like an obnoxious seven-year-old boy, I half-expected the eagle to turn towards me, stick out its tongue, and blow a raspberry. Or pin me to the wall, put on an eerie smile and ask, “El ‘elba dy feeha eh?”

With that thought, my defenses crumbled. “That thing is extremely provocative,” I snapped, throwing an icy coldness onto the otherwise warm atmosphere of the evening. I knew I was firing across the buffer zone, but I no longer cared.

It started with a protestation, grew into an argument, and ended in tears. That night, as I fell asleep, I felt a lump in my throat the size of an elephant.

The square looked different, almost brand new. That is, if you didn’t count the collection of centuries-old antiquities which now stood at its center.

At the heart of Tahrir Square as I once knew it was a large green roundabout, an open space where tents were once erected and protesters swarmed around them like iron filings drawn to a magnetic field. At the center of this 2023 version of the square was a nineteen-meter-tall obelisk belonging to Ramses II, flanked by four magnificent ram-headed sphinxes transported from Luxor. They looked like they had always been there, as if the history of the square had always been pharaonic. As if it was the only history that mattered.

I was back in Cairo for the winter, this time escaping bigger elephants in the tiny boxes of American media and politics. The ones that equated occupation with liberation, confused ceasefire with genocide, and graded human lives according to a hierarchy of value. I welcomed the respite from the assaults of logic-defying mental acrobatics and the comfort of knowing that here, at least, hearts were breaking in the same way.

As I circled the roundabout, I cracked open my car window to breathe in the cool night air, along with the elegant vibes of this new Tahrir. Every building overlooking the square — the pink tones of the Egyptian Museum up ahead; the delicate, French-style apartment buildings to my right; the imposing brutalism of the Mogama’ building behind me — was glowing in a tasteful display of accent lighting. There was almost a fairytale quality to it.

I glanced to my right down the street where I had spent the bulk of my college years. I didn’t need to drive through it to know what was no longer there: the colorful graffiti painted on the walls in 2011, an entire visual history of the uprising. Deleted. Gone.

The massive concrete blocks constructed by the Ministry of Interior had also been removed. I felt a strange sadness at their absence. As much as I hated their hostile countenance, I loved to see them painted into optical illusions that transformed the draconian grayness of the concrete into joyful scenes of city life. It was as if ‘Asfour had broken into a wide smile, snapped his fingers, and conjured an actual elephant out of the box.

Stuck between the erasure of the past and the grief of the present, between the elephants of Tahrir and those of Gaza, I turned on the car audio and tuned in to Cairokee, one of my favorite Egyptian bands.

As I pressed on the gas pedal, I sang along to the lyrics of their absurd satirical hit, “Dinosaur,” sneering with the lead singer at the political fictions of the past decade:

I won’t be surprised,

If I see a dinosaur or a penguin,

At the street corner, scoring [drugs]

I won’t be surprised

As long as memory remains alive, absurdity can be liberating.

I love your work. It’s amazing! I have been to Egypt and Alexandria for 30 years now and I think your work shows the beauty of Egyptian architecture, colors and lights of the great nature and it’s also a work on Egyptian daily life. The soul of Egyptians is in your art.

nice