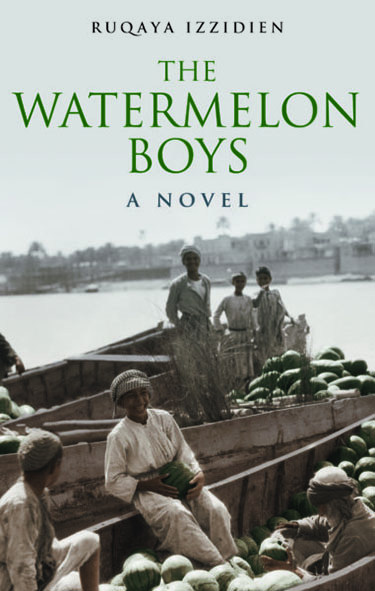

The Watermelon Boys, a novel by Ruqaya Izzidien

Hoopoe Fiction, 2018

ISBN: 9789774168802

Rachel Campbell

Ruqaya Izzidien’s debut novel is an emotional family saga and a compelling work of historical fiction that chronicles the military campaign in Mesopotamia during the First World War. Starting in 1915, The Watermelon Boys begins with Iraq still under Ottoman rule. However, over the course of the novel, the Ottoman Empire falls, the Sykes-Picot agreement divides up the Middle East, and the Iraqi people unite in mass demonstrations against the British during the 1920 Iraqi Revolt. The narrative examines how the events during and immediately after the war affect two men: Ahmed, a Baghdadi watermelon seller who joins the British-led revolt against the Ottomans, and Carwyn, a Welsh teenager who is sent overseas to fight on behalf of the British

The novel opens on the banks of the Tigris, where Ahmed lies, having nearly died in the battle of Ctesiphon after fighting alongside Ottoman forces. Although Ahmed is able to recover from his physical injuries with the support of his wife Dabriya, he still suffers psychologically because of all he has seen and done. Now a defector, Ahmed becomes increasingly concerned about the safety of his Armenian friend Mikhail, living under Ottoman rule. When his closest friend Dawood, a Jewish judge, is rounded up and taken away, Ahmed reluctantly joins the British-led revolt after hearing promises that the British will create a “Baghdad for all Baghdadis” should they defeat the Ottomans. However, when the war ends and the Ottoman forces are defeated, Ahmed is bitterly disappointed, as the British renege on their promises of self-governance. He is left a broken man, having killed fellow Baghdadis, both on behalf of the Ottomans and the British.

Similarly tortured by his participation in the war is Izzidien’s second protagonist, Carwyn, a Welsh teenager who is sent overseas to fight on behalf of the British. Having been beaten in school for speaking Welsh and subsequently losing his father after a miner strike in Wales turns violent, Carwyn similarly holds no soft spot for the British. He nevertheless joins the army at the behest of his mother, in order to escape his abusive stepfather. As Carwyn is sent to Baghdad, he tells himself that he will be a different kind of soldier and that he will rebel in his own way. However, like Ahmed, he finds himself disappointed and wracked with guilt as a result of his actions. As the lives of these two men intersect, Izzidien brings together two distinctive characters and shows the devastating effects of war and colonization. As a Welsh-Iraqi, the author manages to build her novel with the use of multiple perspectives that have frequently been disregarded in mainstream historical and literary narratives.

One of the most potent aspects of Izzidien’s novel is the way she is able to offer up fleshed-out characters with nuance and depth, without disregarding the consequences of their actions. At one point, for example, Carwyn encounters Ahmed’s son Yusuf and confesses the guilt he feels for all that he has had to do for the British army. Yusuf in turn realistically confides that he too has “no time to ease the guilt of a man who was killing his people.”

I read The Watermelon Boys with Adabiyat, an online book club that meets monthly to read and discuss works by Arab authors. That month, the author was invited to attend the meeting, and she answered general questions on the writing process as well as the motivations that led her to write the book. During the discussion, Izzidien pointed out that unlike the British forces, the characters in her novel never referred to themselves as Iraqis, instead attributing their origins to the region of Iraq from which they came, mainly Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul. In the novel, Izzidien clearly alludes to how the circumstances in which the modern state of Iraq was formed have had repercussions that can be seen in the present day: “Men who dabble in war and conquest seldom understand the value of identity,” she writes. “Is there a possession more volatile or valuable? And to steal such a thing, to maim it beyond recognition, triggers a fracture that festers in the veins of progeny for eternity.”

The Watermelon Boys is deeply personal for Izzidien, not only as its creator but as a woman of Iraqi descent. In the author’s note she writes, “On a personal level, The Watermelon Boys reclaims the dominant narrative of the British occupation of Iraq, which was largely written by the colonizer.” Throughout, the idea of who writes and interprets history is something that Izzidien alludes to several times. One instance where this was done involves the character of Ahmed’s wife, who is the backbone of her family. She fights tirelessly to hold her family together, both while her husband is away fighting and when he returns, mentally and emotionally distant and distraught. When her son, Emad, remarks on her bravery, she responds: “I am nothing special, Emad. This is what women have always done, but we don’t write the history books. We rebuild countries, but the stories always end at the victory, so the men, they never talk of our fight.”

It is moments like this where Izzidien almost breaks the literary fourth wall; where, although this novel is a historical fiction set in 1915, the reader is almost able to glimpse beyond the veil to see the 21st-century author who is intending to provide small nuggets of commentary through her characters. Although lines like this are both beautiful and painfully true, they often feel somewhat out of place and create a temporary sense of dissonance.

As this is Izzidien’s first book, and seeing as she is writing a work of historical fiction from a perspective that has been both underrepresented and misrepresented, one feels there is pressure on Izzidien to try to say so many things and make so many points through one novel. However, I think that in many ways, the characters and the narrative in The Watermelon Boys are so expertly written that these moments of commentary are not needed in order for Izzidien to make her desired point. For example, in the novel, Dabriya is explored in depth as a character, and she is clearly depicted as an integral part of her family. I think most readers would be able to recognize her significance and to understand the ways that women’s contributions to history are often overlooked, without the need for Izzidien to directly spoon-feed this idea to them.

The Watermelon Boys is a beautifully written book and merits consideration, not exclusively because of the historical narrative it reclaims, but also because of Izzidien’s talent as a storyteller. Her novel is an informative work of historical fiction about war and colonization, but it is at the same time a novel about familial love and loyalty.