“Water is a shared human resource among all. When I tell a story about the thirst faced by an Iraqi village in the south, the reader, as she reads it, does not ask about the nature of politics in Iraq, but rather expresses solidarity with the humanitarian situation.”

— Khalid Suleiman

In this interview journalist and researcher Khalid Suleiman talks about his new book on the looming threats of drought and climate change in Iraq and explains the special role that art and culture can play in raising environmental awareness in the country. Suleiman makes special note of science fiction works that imagine future worlds of ecological catastrophe: ones in which the ice sheets have melted and Basra has drowned in seawater, or where climate change has made the surface of the country too hot for human habitation. The article gives the example of the story “Graffiti 2042“ by Muhammad Khudair in which residents are driven by extreme temperatures to build a “subterranean” city. During a brief excursion above ground the story’s main character sees a friend of his painting a mural painted with the words:

“Woe to the prophecies which described what would be our ugly distorted lives”

تعساً للنبوءات التي رسَمت حياتَنا الشوهاء

Unfortunately, while environmental catastrophe has already begun to unfold in Iraq, Suleiman claims that practically nobody but fiction writers are thinking seriously about these threats. The prophecies, it seems, are not being heeded. — Matthew Chovanec

Osama Esber أسامة إسبر

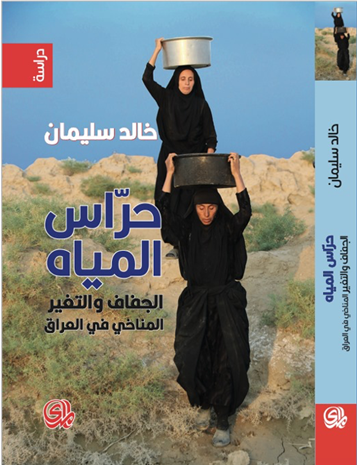

We met with Khalid Suleiman—a writer on environmental affairs with a literary flair—following the publication of his book Guardians of the Water: Drought and Climate Change in Iraq (Al-Mada Press, Baghdad). Guardians of the Water is particularly important at a time when Iraq and other Arab countries are facing an escalation of threats, such as droughts and epidemics. However, Arab governments are overlooking the dangers posed by desertification, water scarcity, floods, and torrents by not taking any meaningful action to stave off these threats and build a secure future for later generations.

Khalid Suleiman is an Iraqi Kurdish theatre actor, journalist and researcher residing in Canada. He’s published many studies in Arabic-language and international newspapers. In this conversation, he attempts to highlight the dire environmental situation in Iraq, and the Arab world in general, and proposes solutions based on the region’s collective experience throughout history.

What motivated you to write Guardians of the Water: Drought and Climate Change in Iraq, and when did you become interested in these topics?

My story with water and the environment goes back to the village where I was born and grew up. Despite its simplicity, life in the village was very difficult because we relied on monsoon rains to sustain ourselves. If there was diminished rainfall for one season, the wells would dry up and cause great hardship for the residents. Although I migrated from the village, studied theatre in the city, and later entered the world of journalism, the image, rhythm, and smell of water never left me. I used to smell the scent of water in the basil seedlings, which my aunt planted in one of the corners of my grandfather’s house.

My story with water is, in fact, the story of more than a billion people who are dealing with thirst today. It has a direct relationship with human nature. Specifically, the relationship between human beings and their environment, and the manner in which they organize that relationship.

It is part of the solution that we are looking for today in order to overcome hunger and thirst. The story is very simply, as I narrate in the book: the relationship of a Kurdish man to a berry tree. The tree was planted inside his small house after he was married and separated from his parents’ larger house. In other words, it is a relationship that derives its solutions from nature and its resources.

“Although I migrated from the village, studied theatre in the city, and later entered the world of journalism, the image, rhythm, and smell of water never left me.”

I opened my eyes in that small house, and I saw there was a berry tree that my father had brought from another village to plant in the new house. He dug a well next to it, which we never drank from, just as the tree did not drink from it. While water did not initially spring up from the well, as we grew older along with the mulberry tree, the well was slowly restored over time. No one in this isolated village taught us how to balance our need for water with the scarcity of water. Water management was conducted through an organic and sensory relationship between the population and the dry landscape where our ancestors had chosen to live.

Each family had a well, and it became common for berry trees to be planted near these water wells. As children, we would be pleased with the sweet berries in the summer. The relationship between the underground water that we received after great hardship and our thirst was based on an innate knowledge of trees and their need for water. In that little house, our well was not blessed with water. But the berry tree grew in length and its branches passed through the walls of the yard, or rather, the land upon which the house was settled continued to grow. The water that my father used to perform ablution everyday was then used to water the tree. I never saw him waste water that he had used for ablution. Instead, he recycled it by watering our beautiful tree, which attracted many birds and turned our house into a true oasis. Following in his footsteps, we—his children—learned to conserve water, recycle it for uses other than drinking or preparing food. The people of the village reused the remaining water in the rivers for livestock and to water small gardens that looked like green oases in our village during the summer.

This was the origin of my interest in water and the environment. But the more immediate reason for this book was my experience with Iraq’s water problems, which Arabic and Kurdish newspapers have written about for years. I often thought about the vast space that separates academic conferences and forums from the daily reality of people. Journalists write a story or a report on water issues based on the narratives of experts and officials. Personally, I do not like this method and I do not want to rely on the narrative of a local or international expert on water and climate change before listening to and relaying the daily stories of people.

Stylistically, this book relies on a journalistic or literary approach that avoids theoretical language. Why did you choose to adopt this innovative narrative style that reads like a novel about yet another tragedy suffered by Iraq and the region?

The numbers, government data, and regional and international agreements shed light on water and the climate for academic and theoretical writing, which is necessary for policymaking and research. As I mentioned in my previous response, many journalists are satisfied with reporting official numbers and data. Personally, I am not only inclined toward a different method, but also toward a different philosophy, one which informs people about what is happening around them in terms of water scarcity using a journalistic narrative style that foregrounds the human-interest side of the story. Water is a shared human resource among all. When I tell a story about the thirst faced by an Iraqi village in the south, the reader, as she reads it, does not ask about the nature of politics in Iraq, but rather expresses solidarity with the humanitarian situation.

In addition, I want to say that finding solutions to environmental crises and droughts in Iraq, and the region as a whole, requires the involvement of local communities for their experience and instinct when dealing with their environment and natural resources. But at the same time, these societies need to understand these changes and their implications for the future, such as climate change, biodiversity, the impact of urbanization, and agriculture on water resources, population growth, high temperatures, etc. In this case, climate change and drought cannot be analyzed based on the numbers provided by physicists and chemists, because local communities require a simple language that they can understand. From this perspective, scientific data becomes part of the journalistic narrative, i.e., simplifying the theoretical academic language on the cases of drought and climate change and turning it into a language that everyone understands. More importantly, the communities most affected by these factors must understand.

This approach to finding solutions through journalistic narratives is a successful approach used today by the global press. On the one hand, it adopts an informative narrative, and on the other hand, it suggests solutions to these problems. Relying on this approach, I was satisfied with the stories recounted by the characters I met in the process of realizing this book. First, I listened to them and engaged with their stories. Then, I took an interest in obtaining the information that I needed for the book.

Your book begins with a legend and arrives at modern Iraqi literature, through the kinds of stories such as Muhammad Khudair’s, and through oral conversations. It is possible to characterize this book as a journey through Iraqi culture by researching the issue of water. So, can we speak about the anxiety around drought and how this is reflected in Iraqi culture and literature?

Water has a great presence in literature, art, and culture in Iraq—in myths, as well as in the Islamic era, and also in modern literature. Even the Sumerian story of creation begins with water. It is present in the Epic of Gilgamesh, the story of the flood with its Sumerian and Babylonian variations, the Code of Hammurabi, and in modern Iraqi literature, as well as in popular arts and culture. We even see a large presence and symbolism of water in the culture of food and types of dessert. For this reason, my work on this book forced me to return to Iraqi texts, literary records, and songs in order to understand the essential role of water in Iraqi culture; for example, the famous Mayhana Mayhana song by Nazem al-Ghazali. In order to preserve this cultural and artistic heritage in the collective Iraqi memory, we must talk and think aloud about what might happen if this issue and the cycles of drought worsen. Yes, culture and art die in the absence of water.

We could read the story Graffiti 2042, by the Iraqi writer Muhammad Khudair, as a warning for the future. He talks about life on the Earth’s surface fleeing from heat. What is the future that awaits Iraq in light of this prophetic warning? What is the scenario that is imagined?

Muhammad Khudair wrote many anecdotal texts about southern Iraq’s environment and its relationship to water and the marshes. But what surprised me in the story Graffiti 2042, which in terms of climate change literature is an excellent work of art, is how rising temperatures that cannot be tolerated by human beings drive them to live underground, or to build a “subterranean” city, so to speak. In the context of this conversation, it is possible to return to the story of a female farmer in southern Diwaniya, who I interviewed in order to document how she dealt with rising temperatures. She provided a clear image of current high temperatures, since she works on the ground and feels the details of each day working under the hot sun in the summer. The agricultural work that she used to do in September in the 1980s, she now does in the month of October, sometimes November, due to the fragility of seedlings in the face of overwhelming heat that now extends into the month of November.

The storyteller Muhammad Khudair has a high literary sensitivity to water and the climate. He has covered them in more than one story, not to mention his articles on the same topic, especially given that he lives in Basra, which is not only a source of water and salinity, but also a source of heat in Iraq. So, I not only read his texts, but also went to meet him in Basra to talk to him about the role of water in Iraqi literature. In brief, he examines the movement of people through the movement of water. However, there is an important point that should be mentioned in this context. The population of Basra, which has been suffering from these rising temperatures, is also threatened by flooding in the middle of this century due to rising sea levels caused by the melting of ice in Antarctica and Greenland. Of course, no one in Iraq talks about this threat today. When I tried to obtain information from researchers and specialists about this impending catastrophe, I learned that nobody had access to this information despite recent digital photos from space agencies and international universities that illustrate this phenomenon.

Of course, it is not possible to imagine the lives of people and the ways that they will cope with increased heat, as reflected in the story of Muhammad Khudair. There remains the possibility of coping with higher temperatures, which exceed fifty degrees centigrade in summer, but what if it were to rise more? The answer is not limited to human life, as we have the option to retreat into basements or subterranean cities, but what about animals, insects, and plants? Can a human being survive without biodiversity? Certainly not. For all of these reasons, Iraq faces great challenges in the future, and we must be prepared to confront them.

The God Enlil decided, as you say in the book, to punish people for their proliferation, hustle, and bustle on the ground, by sending them floods and droughts. This reflects an earlier awareness of the dangers involved in violating the environment. Now, in the face of climate change, is there anyone in Iraq who expresses this kind of anger?

The Babylonian deity Enlil held the fervent determination to get rid of the people after their numbers and noise on earth increased. Enlil chose to inflict epidemics and disease on people in order to eliminate them. From here, the hero of the Babylonian story of the flood (Atrakhasis) intervenes. He is the savior of biodiversity, as he protects one pair of each animal on his ship, and calls on the god of wisdom and water (Ea) to save people from the epidemic. Ea responded to his calls and guided him to a path where he could save people from their plight. Enlil then returns in a later period once again to impose epidemics on people through drought and flooding. This was because the relationship between the world of the gods and that of human beings returned to the state of their predecessors, when the number of people increased in such a way that Enlil could not bear.

If politicians and rulers in Iraq had read the ancient history of their country, they might have used some of the laws they had left for us and for humanity. But there are very complex problems and crises in Iraq today: a political system based on quotas, corruption, tremendous population growth, old and dilapidated urban infrastructure that leads to flooding, and dirty water minutes after rainfall, constant power cuts in summer and winter, and high levels of air, soil, and water pollution.

It could be said that the popular protests that began in October are a part of this anger, albeit indirectly. Imagine living in a big city like Baghdad, where nine million people live under high heat, power outages, and a lack of services, such as public libraries, gardens, cultural, and social centers. So, where do people go? To the mosque or arenas of protest despite harsh environmental conditions. One of the clear paradoxes in Iraq today is that basic services are provided by mosques, whereas schools and libraries lack them. Therefore, there are schools in villages and towns whose students turn to the surrounding mosques for washing and relieving themselves because their schools lack these basic services.

While writing, I was asking myself whether someone could prevent a catastrophe in Iraq today, as the God of Wisdom (Ea) did in ancient Iraq.

In addition to politically and economically devastating their homelands, corrupt Arab politicians are also destroying the environments of their homelands. How do private farms, fish-breeding lakes, monopolized investment projects, stolen water, and artificial tributaries that support the private projects of politicians and their properties harm the environment?

What is happening in Iraq due to corruption and theft is beyond our imagination. The things I have heard and documented, and which I could not document due to a lack of interviews and incomplete data, will make one’s hair turn gray. Yes, there are politicians who steal water for their own farms, and no law holds them accountable. There are members of local governments, provincial councils, and members of parliament who have farms and fields for raising fish and buffalo at the expense of water bodies and biodiversity, and of course the costs are borne by the people.

Politicians in Iraq do not care about their country’s environment, biodiversity, natural systems, and natural resources. They have turned the country into a warehouse for Turkish and Iranian food products. Iraq is no longer a productive country, despite the fact that in the past it was the region’s breadbasket. We have seen how difficult economic conditions become when the global price of oil fell amid the coronavirus pandemic. While working on and researching this book, I asked people about the importance of protecting water and biological diversity. They answered that such questions should be directed to politicians, rulers, and influential people, since they are the ones who violate nature, biodiversity, and water.

The issue is not only of the exploitation of water and other natural resources by influential people and politicians, it is also the lack of legislation protecting Iraq’s environment and its biodiversity and natural resources from daily violations. A researcher in southern Iraq said, you can kill anything that moves, and there are no laws preventing this, so the ecosystem in Iraq is vulnerable to killing and hunting. Hence, the government and its institutions bear the responsibility for the level of devastation and environmental degradation reached today.

How did Saddam Hussein use water as a weapon to suppress the population? What exactly did he do?

The environmental damage that took place during Saddam Hussein’s regime requires specialized, independent research, because the scale of the damage that occurred was so great: razing the palm groves during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), drying the southern marshes after the second Gulf War in 1991, depositing war-related materials in rivers and water basins, displacing local communities and uprooting them from their local environments, and destroying Kurdish land through the proliferation of landmines. Each of these instances require further research in order to formulate responses and improve the environment. After the fall of the regime in 2003, the reality of the environmental collapse was unchanged and the most heinous, illegal, and immoral exploitation of what remained of the environment continued. I was shocked to see military ships destroyed in the Shatt al-Arab in Basra during the 1980s, as the river turned into a museum of destroyed warships.

You have spoken about how hundreds of villages in Iraq have suffered from miserable health conditions due to the lack of water drainage networks in the winter and water scarcity in the summer. Is this situation getting worse? What might this lead to?

The conditions that most Iraqi villages live in are tragic in the full sense of the word, because they lack health facilities such as sewage networks, potable water, and electricity. Dermatological diseases are common in some villages due to the reliance of their inhabitants on salty water bodies, which also contain high levels of harmful chemicals, such as sulfur. Yes, this type of environmental and health situation exists in many villages. It will lead to serious disease among the population, especially among women and children, because they have the most contact with water in their daily work. I am specifically speaking about women, because they bring water from polluted rivers to their families using traditional means and use this water for washing and cleaning. In short, Iraq is on the brink of a health and environmental catastrophe if these conditions continue.

How does climate change affect the decline of education in Iraq?

There are several consequences of climate change that affect the process of education in Iraq, such as high temperatures, droughts, and floods. With regards to the increase in high temperatures and the prolongation of summer due to climate change, most of the public (government) schools do not have air conditioners. At the end of June 2019, the temperatures were approximately fifty degrees centigrade until seven o’clock in the evening in the southern cities.

The educational policy in Iraq does not take climate change into consideration, neither in terms of infrastructure, nor in terms of education. There are temporary solutions to fluctuations in weather that depend mostly on daily or weekly changes, but not on the long-term impact of climate change. These solutions do not adequately address the future challenges posed by global warming. For example, on 13 June 2019, the Directorate General of Education in the capital Baghdad (first Rusafa) distributed air coolers to its exam centers to help students pass exams under high temperatures that approached the boiling point. However, climate change requires permanent and long-term solutions that are related to the environmental specificities of Iraq.

In Iraq, students cannot wash their faces and hands at school; they are afraid of skin diseases that are caused by polluted water. The polluted water has led many students to leave school, according to UNICEF. I should also mention the dust storms that have become part of the daily life and environmental reality of the people. The increasing desertification caused by receding rivers and lack of rain leads to the disruption of both agricultural practices and food production. The effects of climate change and the expansion of urban areas have begun to manifest on the production of dates, sesame, rice, and other types of key nutrients, not to mention fish and livestock in Iraq.

This decrease in food production results in child malnutrition, particularly in rural areas, where approximately twelve million people live today. It is well-known that children in primary school need good nutrition and sufficient calories to be able to learn. Without this, students risk failing classes, experience fatigue, and there are high rates of skipping school. In addition, in recent years, torrential floods have led to the closure of schools in more than one region in Iraq due to their severity and destruction of many homes, bridges, roads, and the interruption of services. Schools have been affected by these floods at a higher rate than other institutions. This, and the lack of educational infrastructure in Iraq, exposes primary and middle school students to many health and educational risks.

What role did the successive wars and weapons testing play in destroying Kurdistan’s environment? And how did this affect birds and wild animals?

Kurdistan, due to its proximity to the Mediterranean, and its differences from Iraq’s other regions, is conducive for biodiversity. Many kinds of birds migrate from all over the world to the region during breeding season. However, throughout its long history, the region has often been a hotspot for many devastating wars. For example, during the wars under Saddam Hussein’s regime and the scorched-earth policy at the end of the 1970s and 1980s, more than four thousand villages were destroyed during a genocidal campaign, named “Anfal” (“spoils of war”) by the regime, demonstrates the extent of the damage to Kurdistan’s environment. In addition, the region has been exposed to continuous bombing on its borders with Turkey and Iran, forest fires, the destruction of animal habitats, internal wars among Kurdish parties that have damaged the environment in the region, and the massive effects of logging conducted by the population in the 1990s. The increase in logging was due to Saddam’s regime siege imposed on Kurdistan, which rendered trees as the only source of fuel for heating and cooking for Kurdish villages and towns.

Another issue, which is no less important, is the overfishing that has led to the eradication of birds and animals in some regions. The war with the Islamic State has caused the spread of black-market contemporary machine guns that have been used for poaching and unlawful killing (for immoral and inhumane transportation), exacerbating the situation of wildlife in Kurdistan. There are projects to establish natural reserves in Kurdistan, but the local Kurdish government has invested all its effort in oil, in the service of a ruling elite who is not overly concerned with environmental issues.

The above photograph, included in Chapter 10 of your book, refers to the role of climate change in social conflicts, as I pointed out in an article that was previously published by al-Hayat on the role of climate change in the Syrian conflict. How does climate change play a role in social conflict and how is this manifested?

Since the mid-1990s, Syria has been suffering from high levels of water scarcity and drought. One report on water, published by the World Resources Institute on 25 August 2015, explained that between half a million and a million peasants left their farms and livelihoods to migrate to cities due to water scarcity, which negatively affected the overall stability of the country. The same report pointed out that fourteen Arab countries topped the list of thirty-three countries in the world that were facing water shortages two decades ago. Among these countries are Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, Palestine, Qatar, Iran, and Israel. It also indicates that poor management, wastefulness, and overpopulation are additional factors in the droughts that hit several regions of the world due to global warming and climate change. The Middle East is one of the regions that will be hardest hit by drought and severe water shortages in the future.

The story, simply put, is that migration resulting from drought and water scarcity leads to social, political, and economic conflict, because those fleeing from harsh climatic conditions to cities require work, food, water, and energy. Cities, however, are already facing difficulties in providing services, infrastructure, and job opportunities. At other times, severe water shortages can lead to conflict between communities, as happened in Iraq in 2017.

Historically, these mass migrations have contributed to “instability,” and if mass migration was previously caused by war and violence, today it occurs because of climate change, water scarcity, and shortages of basic resources. This could lead to even more violence in the future if solutions are not developed and local communities are not empowered to manage their resources better and improve their environment through solutions derived from nature. If nature and natural environments are not improved, other solutions are difficult to achieve.

The effects of global warming cross borders. How will global warming affect Iraq in the future if the situation worsens, considering that Iraq, along with some other countries in the region, claims that it produces not more than five percent of the greenhouse gases responsible for exacerbating global warming?

The effects of climate change, due to rising greenhouse gas emissions, are not limited to the location where the gas is first emitted. For example, the United States and China are the largest producers of greenhouse gases, but the effects are felt everywhere around the globe. Not only Iraq, but the entire Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, generates no more than five percent of greenhouse gases. But the region is affected more than others by climate change due to its semi-arid landscape, since it is not covered by vegetation, and suffers from a scarcity of renewable natural resources, not to mention population growth, and an increased demand for food, energy, and water. For example, the proportion of freshwater in the region is less than two percent of the freshwater available globally, while the population is more than six percent of the total global population. This imbalance between natural resources and the population is a major factor in the impact of climate change on Iraq and the MENA region as a whole.

Since the industrial revolution in the mid-nineteenth century, industrialized countries have generated large quantities of greenhouse gases and they are primarily responsible for climate change. However, fragile regions, which have less renewable natural resources, pay the price for this. This is applicable not only in Iraq, but in all the countries in the region as well as other regions in the world, such as Africa, Asia, and Europe. Today, on the African continent alone, more than fifty million people suffer from poverty and destitution due to drought and climate change, while people in Asian countries suffer from poverty due to floods that are also caused by climate change.

Are you talking about the need to change prevailing cultural norms, in order to better understand an individual’s relationship to their environment? How can this be done in a region dominated by tradition and authoritarian polices which are indifferent to the collective fate of the population, and ignorant of the dangers that lie ahead?

As previously discussed, official policies in most countries in the region lack plans to tackle climate change. Any program aiming to improve the environment and reduce damage to local populations must involve five core constituencies: local governments (governorates or regions), the private sector, academia (universities and scientific institutions), local communities, and international organizations. With regards to the centralized government and the absence of decentralization among the countries in the region, together with a lack of specific departments responsible for environmental policy, it also seems difficult to speak about the role of the private sector, because it is also connected to governmental policies. Therefore, the discussion focuses, on the one hand, on the role of universities and scientific research on drought and climate change, and on the other hand, the involvement of local communities and their innate skills in adapting to change through the work of civil society organizations with the help of international institutions.

Ancient cultural norms have been based on fantasies and myths, because they have viewed water as an inexhaustible natural resource. Instead, the present condition reached by humankind has positioned us on the precipice of the downfall of cities, civilizations, and cultures due to water scarcity or rising sea levels caused by the accelerated melting of glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica.

I think we need to change cultural norms, change the way that water is consumed, managed and recycled, and we need to restore wastewater or stagnant water, and take into consideration the water in trees, food, and air. Wasting food is tantamount to wasting water; razing green areas in favor of excessive urbanization is also wasting water, because green spaces, in addition to being a sign of a healthy, natural system, also contain water, despite their color being green not blue. Heavy wastewater is not actually wastewater, as it is commonly termed. Instead, it could be used for recycling and consumption. Human waste can be converted into energy, as is done in many European countries nowadays. Considering all of these aspects, we need to change our overriding culture in relation to water and look to the future rather than remaining in an ancient world that is measured and managed with reference to a “profane” culture.

It is often said that when Adam Smith tried to calculate “the value of water,” the value of water ended up exceeding the value of oil. What political changes could this bring about, and can we talk about conflict over sources of water and how this might change the nature of wars in our region?

The conflict over water is already underway. Countries that control the sources of international rivers use it as a weapon against countries located further downstream or where the river passes through. Turkey’s current policies regarding, and control of, the international Tigris and Euphrates rivers are a perfect example of such a conflict, as are Ethiopia’s policies toward the Nile, and Israel’s policies toward the Jordan River. However, these policies, which are restricting the flow of water, may harm countries located upstream as well, because if local populations are exposed to drought, thirst, and loss of their livelihoods, they will not remain on parched land. Migration in search of water is a human choice and right, and thirst does not recognize international borders. Water, like air, cannot be trapped and prevented from moving.

When Adam Smith was discussing the value of water in the eighteenth century, Europe in general, and Scotland in particular, suffered from cold and high levels of humidity due to heavy rains. However, water still occupied a primary position in his economic thought. Smith’s comparison of water and diamonds reminds us of the essence of water, not only in myths, stories of creation, philosophy, and literature, but also the intrinsic value that man places on human life before all other natural resources. Yes, today the price of water is more expensive than the price of oil, but huge amounts of it are wasted every day. And yet, international security companies protect oil resources and are careful not to waste a single drop. Despite the fact that Adam Smith discussed the scarcity of water, we still prefer diamonds over water and do not appreciate the value of the latter. It is the great paradox of our culture.

Translated by Huma Gupta from a conversation with Khalid Suleiman & Osama Esber in Arabic. This interview appears in TMR courtesy of Jadaliyya.

1 comment