In which Washington DC’s ardent artist-entrepreneur-philanthropist (and one-time mayoral candidate) dishes on matters of hunger and racism.

Jordan Elgrably

In a recent conversation among the editors at The Markaz Review, we discussed the rising threat of starvation among people in Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria and other countries, and as a result decided to devote an issue of TMR to the subject of food and hunger. According to the World Food Programme (WFP), in 2022 “up to 811 million people do not have enough food.” The Covid-19 pandemic and recent conflicts across the globe have brought millions to the brink of famine. The war in Ukraine has made Europe part of this discussion, even as more than 39 million Americans, including 12 million children, according to the USDA, “are food insecure.”

In Gaza, Palestine, the WFP reports, hunger effects more than 64% of the population. “Severely food insecure Palestinians are suffering significant consumption gap and lack the means to cover their basic needs including food, housing and clothing,” notes the WFP.

It must be said that with the war in Ukraine, we have observed firsthand how much more Ukrainian refugees have been welcomed, fed and housed, as opposed to the rather disgraceful reception experienced in recent years by people fleeing conflict in Syria and Afghanistan, for instance — quite as if there is a double standard for white Christian Europeans versus Arabs and Muslims.

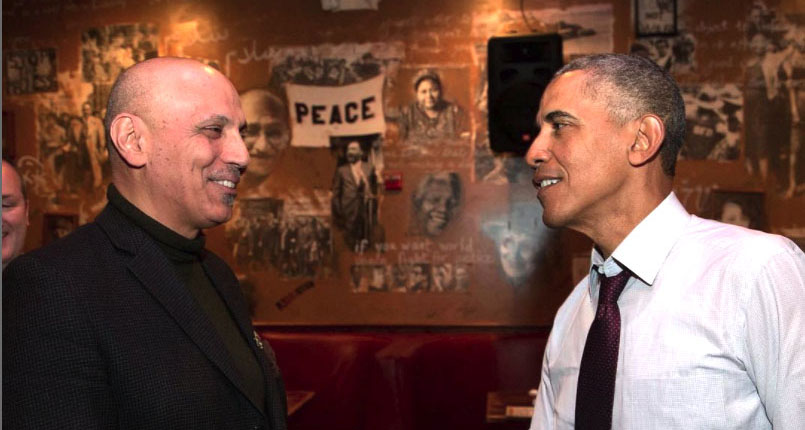

In thinking about the intersectionality of hunger and race, my mind went first to two movers and shakers in the Washington, DC area — Spanish-born chef José Andrés*, who has devoted recent years and millions of dollars to feeding hungry people, from along the US border to Haiti to Ukraine, with his nonprofit World Central Kitchen; and Iraqi native Anas “Andy” Shallal (أنس شلال), the founder of the Busboys and Poets chain of restaurant-bookstores.

When he was 10 years old, Anas Shallal left Baghdad with his middle-class family, arriving in the United States in 1966. Shallal’s father was ambassador for the Arab League in DC, a position he held until Saddam Hussein seized power, after which he did not feel it was safe to return. Growing up in Arlington, Shallal went to public school and with his siblings, tried to blend in. While many Arab Americans pass for white, Shallal has passed for Black, and more than once has been confronted with the awkward question, “What are you?”

Race is important to Shallal and he encourages frank discussions about race at work. As a recent story in the Washington Post noted, one of the aspects Shallal loves most about supervising his 600 Busboys and Poets employees is that every few weeks, he attends new-hire orientations, where there is an open discussion about race, discrimination and serving customers, in which “employees gather around a table … to discuss their fears, their pasts and their experiences with race. It’s an approach Shallal has refined over decades and one that is increasingly urgent as hourly wage workers are on the front lines of America’s race wars — and often ill-equipped.”

As he once explained, “I didn’t think I was white and I didn’t think I was black, and no kid wants to be the ‘other’” — but from time to time, he remembers, kids in school would say to him, “What are you?”

And it’s funny, because my brother looks more white than I do. And so he did not have the same experiences I had. I have two sisters also. One of them looks African American. She could easily pass for a light-skinned African American. The other one looks like she’s Italian or French, you know, completely European-looking. And so when I talk to my sisters, the darker sister and I have much more in common of how we interpreted race than my older siblings, who were lighter and had a whole different experience. [Analysis]

Shallal graduated with a BA from the Catholic University of American and then enrolled in Howard University’s medical school. He went on to become a researcher in medical immunology at the National Institutes of Health, before going back to school to earn an MBA at the University of Maryland. Unlike his engineer brother, Shallal did not stay on the straight and narrow path. Instead, he realized that he loved the experience of meeting new people at the small pizza restaurant his father had owned, and he determined he would combine his passion for African American culture, food and progressive politics, to create a space that brought together his diverse interests.

Shallal has worked with chef José Andrés and others on food relief projects. During the Covid pandemic, he observed that people of color took it on the chin, more than many white folks. Hunger and food scarcity have been a major concern, but he says, “DC is an impressive city and it has really done a decent job in making sure nobody’s left behind in this situation.”

Shallal acknowledges that Busboys and Poets has partnered with the city government and “with World Central Kitchen to provide meals locally, because I think sometimes we forget that while we’re helping people in the rest of the world, we’re not seeing the people in our own backyard. Sometimes it’s easier to work with people thousands of miles away than it is to work with people that are on our doorsteps. I think José Andrés is doing great work. However, I did tell him that I think we also need to focus on areas that are not always in the news, places like Yemen, like Eritrea and Ethiopia, places like Palestine, where there are issues insofar as food and access to food are concerned.”

There is no question that a lot of people are hungry in Yemen, Gaza, Syria and Afghanistan, to name but a few countries that should remain on our radar.

“Yes, and in Iraq,” Shallal says. “Let’s not forget that people who have a voice and a megaphone are empowered to highlight those places, because oftentimes, as you know, people get forgotten. I mean Yemen is a real disaster [with millions facing food scarcity]. That’s happening today in Ukraine and they’re getting a lot of support, people are going insane here, raising billions of dollars for Ukraine, you know, but let’s not forget Yemen and these other countries. At times, it feels a little lopsided. I’m all for the Ukrainian people and I want everybody to be safe and fed, but I also feel like sometimes we go for the shiny thing and we don’t really care about those who are more desperate.”

Besides the eclectic menu that includes Arab dishes as well as soul, vegan and comfort food, most familiar at Busboys and Poets are the murals of major civil rights figures and writers, and the fact that the original Busboys and Poets, which Shallal founded in 2005, was named in homage to Langston Hughes. These are places where conversations on race are encouraged. Shallal’s restaurants are also bookstores and cultural centers and bars, where people converge for author readings, conferences and political events. As the Washington Post observed, Shallal has tried to “create a melting pot of employees who believe in equality. And his restaurants take on a feeling of a community center — with poetry slams, book readings and film screenings.”

It’s hardly surprising to learn that Shallal considered anti-war activist and historian Howard Zinn (A People’s History of the United States) his friend and mentor, and the late novelist-essayist James Baldwin his inspiration. He has hosted friends and acquaintances from the Black and Arab communities in speaker events that include author-activist Angela Davis, Senator Corey Booker, Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, Nikki Giovanni, Cornel West, Danny Glover and Michael Moore.

Shallal is also an artist who has painted murals at several of the Busboys and Poets locations. And as a board member of the Institute for Policy Studies, a DC think tank located four blocks north of the White House, he painted a conference room mural that features Martin Luther King, Jr., Benjamin Spock, the late Senator Paul Wellstone, and late Chilean diplomat and IPS fellow Orlando Letelier and his assistant Ronni Moffitt, who were killed by a car bomb on DC’s Embassy Row in 1976.

It doesn’t take an artist to support artists, but it doesn’t hurt, either: during the pandemic, Shallal hired local broke and underemployed artists to paint murals at the seven DC-area Busboys and Poets restaurants.

Andy Shallal is an excellent oxymoron — a wealthy progressive who cares about his employees and about the quality of the food his customers consume, and a CEO who has often been seen volunteering for the homeless.

For Shallal, who says James Baldwin is his favorite writer (“we had a James Baldwin book club that I led for a long time”), food remains part of his progressive thinking on social issues.

“Food is vital to me, because it’s a common denominator that brings people to the table, literally and figuratively,” he says. “It’s also the engine that drives the machine — when we started Busboys and Poets, I considered organizing it as a nonprofit, and I thought about how nonprofits struggle. I’m on the board of several nonprofits, and they are always at the mercy of the funders, and I didn’t want to be in that situation; I wanted to have the freedom to do the things I wanted to do, without having to pass by some test that a funder wants you to undergo. So,” Shallal mused, “food became the way that we make enough money that we’re able to continue doing the programs that we do. And the type of food that we serve has to be such that it allows people to enter wherever they want to, whether they want to just come and have a cup of coffee and leave, or a full meal, so it had to have lots of options for different people, and different types of dietary options, whether they’re vegan or vegetarian or don’t eat glutin — we wanted it to be a place where we could bring everybody to the table.”

Shallal was always hyper-aware of being an Arab American, and he was also staunchly anti-war. In fact, he was such a vocal opponent of the second Gulf War in 2003 that when he first opened the original Busboys and Poets two years later, it was immediately successful in part because of his anti-war activism and critique of the George W. Bush regime. In addition, Shallal has worked on several Arab-Jewish dialogue projects, with The Peace Café, Seeds of Peace and Abraham’s Vision. And yes, Busboys and Poets has been a central actor in fighting hunger and homelessness in the DC area.

Food for Shallal is the lure, “but I always think that food is a means to an end and not the end itself,” he says.

One Thanksgiving season, he remembers, Busboys and Poets “prepared a large meal for homeless people, and we put the word out to all the shelters, telling them their clients could come and eat on Thanksgiving Day, and we had all these volunteers, and we made this wonderful meal, you know, everything fresh…All these people walked in, and we paired them up with volunteers. One guy who came in by himself, probably in his 40s, we paired up with a young woman volunteer, and she sat with him for hours — they were eating and chatting for a long time. At the end of the meal, he came up to me and asked, ‘Are you the owner?’ and he said, ‘I just want you to know that today I had planned to commit suicide, because Thanksgiving is a painful day for me.’ As for many people who are homeless, holidays tend to bring out a lot of anxiety. And he said, ‘I was going to commit suicide today had it not been that you guys were open and had it not been for the woman sitting here and talking with me.’ At the time I felt like maybe we were literally saving lives here. It really shows you the power of meeting people and the power of food, and how important it is.”

* Despite multiple attempts, José Andrés proved unreachable as he hopscotched across Ukraine, traveling between more than 10 locations where massive kitchens were operating to feed migratory Ukrainians.