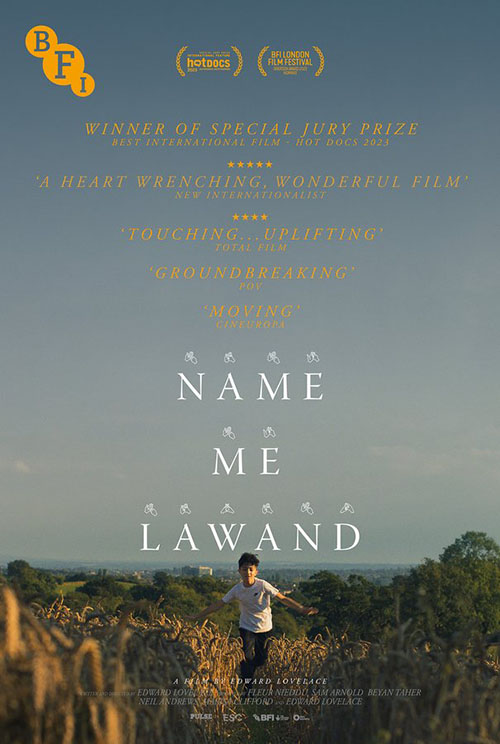

Name Me Lawand is written, produced and directed by Edward Lovelace. A Pulse Films production with support from BFI Doc Society Fund (awarding National Lottery funding) and Electric Shadow Company. In UK cinemas from July 2023, on BFI Player August 21st. (More screening info.)

Nazli Tarzi

Edward Lovelace’s latest feature documentary, Name Me Lawand, is a coming-of-age account of a deaf Kurdish Iraqi boy and his experience learning British Sign Language (BSL) in the English city of Derby in the East Midlands. The immersive film enables the viewer to take in the world through Lawand’s gaze, while also conveying salient messages about the rights of the deaf community and (un)belonging.

Lawand Hamad Amin was born into a hearing family in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), where provisions for deaf children are near non-existent, educational opportunities have been eroded by conflict and occupation, and trauma is as common as a winter’s cold. His family made its way to the UK in 2016, when Lawand was five years old. In the film, we first meet Lawand as a 12-year-old boy in Derby.

Like his brothers and cousins, Lawand is identifiably Kurdish, enjoying the same food and cultural rituals. But in the absence of a common language, there appears to be a divide between them, as well as between him and the speaking world. Rawa, Lawand’s older brother, strongest advocate, and best friend, is sensitive to the boy’s sense of estrangement; “born on the wrong planet” is Rawa’s way of making sense of it.

Lawand’s capacity to use phonetic expression is severely limited, but not non-existent. This fuels hope among his immediate family that the trickle of words he is able to muster (albeit with great difficulty) will become a flood. That does not happen and, eventually, the family accepts that his trouble with speech is not a reflection of a cognitive shortcoming, but rather is informed by his profound deafness.

The film’s twin themes — a deaf boy’s journey to articulating himself in a hearing society, and the humanitarian crisis on the fringes of Europe—move along separate tracks. They occasionally intersect, but each has its own distinctive tone. Scenes that recall moments of the family’s journey out of Iraq are abstracted like a bad dream slipping away, in contrast to scenes of the family’s current suburban life in Derby, which are upbeat, colorful, and told through slow and languorous depictions, like a pleasant daydream.

It is a characteristic of both conservative and war-weary societies — Iraq is both — that human differences, in any shape or form, are either egregiously misunderstood or labeled an aberration. Lawand knows this instinctually from experience, having spent part of his childhood in Iraq. Derby, on the other hand, injects color into his monochrome world and serves as restitution for everything he grew up without. At Derby’s Royal School for the Deaf, Lawand is introduced to Sophie, a deaf activist and artist who will be his teacher. Like Lawand, she first learned sign language as a teenager — much later than is recommended by audiologists. With Sophie’s help, Lawand discovers himself and establishes his place in an inclusive and educationally progressive setting.

Midway through the film, however, Lawand and family receive earth-shattering news from the Home Office: they are to be deported. This bombshell galvanizes the teaching staff at Lawand’s school as well as members of the local community, who make every effort to fight for the family’s right to stay. Through this plot twist, the film’s narrative swerves in a new direction, heightening our awareness of the double bind Lawand faces as a child who straddles underrepresented communities — the deaf on the one hand, and refugees on the other. Audiences can almost feel anxiety simmering in Lawand’s two worlds, at home and at school, as his fate hangs in the balance.

In many ways, the film is driven by the close bond between teacher and pupil, and in particular the empathy that Sophie radiates. This is best captured by Lovelace in the scene where Lawand is introduced to Visual Vernacular (non-verbal storytelling) by Sophie through her reenactment of the famous bullet-dodging scene in The Matrix, which Lawand playfully mimics in acknowledgment. “See, I can do it,” he then tells her via hand signs.

Fly-on-the-wall moments like these — of which there are plenty — offer more than just insight into Lawand’s life. The viewer is confronted with rarely contemplated questions: What is language? How does it function, and is it necessarily an auditory medium? As someone whose younger sibling was mute until the age of six, I’m reminded of my own experience as a young caregiver, and also of the view that “human bodies are words,” as stated memorably by American poet Walt Whitman.

At another point in the film, Sophie asks Lawand if he would prefer to communicate through his voice, which his family is keen for him to utilize, or through BSL. Lawand unhesitatingly answers, “BSL,” which becomes his primary means of communication. Like a racehorse out of the starting gate, he takes off and never looks back.

As recognition of his school’s dedicated support for Lawand grows inside the Amin household, his parents decide to overcome their initial reluctance and learn BSL themselves. Their learning curve is much steeper than that of Lawand, whose classroom environment is more conducive to the task. For years, Lawand had no choice but to conform to those around him, but in Derby the tables are turned. His family must now adjust to his choices in search of the common ground promised by BSL.

Beyan Taher, one of the film’s producers (and, I should disclose, a friend of mine), was keen to include in Name Me Lawand Iraq-filmed archival material that she shot herself. Scenes include the mountainscapes of northern Iraq, and Rawa and Lawand’s primary school in Chwarqurna, which is located in the governorate of Sulaymaniyah. This gives the film an air of hyper-poetic realism. A poetic texture is also achieved by Lovelace’s inclusion of introspective commentary from Lawand’s family members as they reflect on their changing attitudes towards Lawand’s learning needs. Their choice of words in Kurdish and their cadence feel almost lyrical, and in my opinion as an Iraqi, subtly mirror poetic expressions in Iraq.

The film’s most cherishable moments, however, are those that remind the viewer that love is not contingent on spoken language. Even in its absence, bonds can be cultivated. The exclusion that characterized Lawand’s earlier years as the only non-speaking member of his family may well resonate with children from multilingual households where not everyone speaks a common dialect or even language.

Lovelace’s feel-good, buoyant film makes for great viewing, but owing to the limited snapshot it offers into Lawand’s new life, the viewer is left with unanswered questions about the way that his family is affected by their dislocation from Iraq. Rawa in particular carries with him a profound nostalgia for his native country. For me, the film felt like the first episode of a series: I yearned to learn more about the personal lives of other family members, the challenges that Lawand’s impairment poses for them, and I wanted to follow Lawand’s progression at school.

Though not for the weak-hearted, Name Me Lawand is a poignant portrait of self-discovery and growth. Through a dreamlike aesthetic, it captures the world from the vantage point of a deaf child. The film is also a powerful reminder that asylum policies must account for children with special needs. Lovelace prompts us to think of the UK’s discriminatory immigration policies and the weaponization of the law against social groups for whom home is, to borrow the words of poet Warsan Shire, “the mouth of the shark.”