New SWANA films respond to genocide and starvation. The Encampments and Sudan, Remember Us serve both as witness to suffering but also act as a call to action, urging viewers beyond passive consumption of the big screen.

There is a chilling sense of uncanniness to watching Michael T. Workman and Kei Pritsker’s The Encampments in the summer of 2025. Audiences accustomed to the documentary film genre might expect to sit through a retelling of historical events, but the catastrophe of the past 22 months — that is, the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people at the hands of Israel and its Arab and Western accomplices — is so far-reaching that it has almost destroyed the concept of linear time itself. The present agony over Gaza has merged into a recurring past — that being the enactment of a second Nakba and its attempt to blot out the future, the liberation of Palestine and by extension, the world. We are enduring a permanent October.

Although released only this March, the documentary has last year’s widespread pro-Palestine university encampments as its primary focus. The encampments themselves are long gone, leaving behind the ghostly presence of the solidarities that formed among the tents and the institutional repression, which tore them asunder. So when scenes of students at Colombia University raise their voices in outrage and sorrow at Palestinian deaths are dated to April, of 2024, one perhaps unintentional effect of the film is the reflection on how little has changed since.

The Encampments incorporates archival footage of the 1968 student occupation of Hamilton Hall — also occupied in 2024 and renamed Hind’s Hall, in memory of five-year-old Hind Rajab, killed along with her family and paramedics by the IDF. That the student protests in support of Palestine took on forms inherited from previous generations — sit-ins, teach-outs, occupations, horizontalism and the demand to imagine better — should not surprise anybody. Indeed, by inviting comment from activists like the former Panther 21 defendant Jamal Joseph, the filmmakers purposefully tap into a historical trajectory where the demonized radicals of yesterday are heralded as pioneers by the very establishment they railed against.

Mirroring ’68, the present-day forces of authority dutifully took their place on the opposing side of the barricades. The disgraced, now former, NYPD commissioner Edward Caban offered a particularly hammy appearance worthy of nomination for a Razzie. In the aftermath of the police raid on Hind’s Hall he shook a lock and chain at a news conference that culminated in the well-practiced line that New York’s Finest “will never be locked out” by students.

The Encampments also showcases the made-for-soundbite accusations by politicians and media commentators. One scene shows a condescending Joe Scarborough glaring down from his desk at MSNBC as he lambasts “white, woke, pampered, elitist… children” (he means students) for having the gall to sympathize with the oppressed. This contrasts with the reality beyond cushy TV studios of a multiethnic, diverse, and community-based movement, which has drawn in new constituencies on the basis of a common humanity and who see in Palestine a familiar struggle, from the conquest of Indigenous land in the past to the occupation of Kashmir today.

The documentary draws to a close with the persistent optimism of Mahmoud Khalil. The use of the title card straight afterwards in effect throws cold water on his words almost as if the directors lose confidence in his hopefulness and backtrack to say, “We know what’s going on, we’re not that naïve” — or it could be a sober nod to the stepping up of domestic repression. The conclusion also betrays a sense of prematurity on the directors’ part.

In the same month as the film’s release, Khalil was detained by ICE agents and threatened with deportation despite having a US green card. Time, it seems, again collapses in on itself.

The screening of The Encampments held last month at London’s Reference Point included a post-film roundtable with veterans of the UK’s own student encampments. Chaired by Hazem Jamjoum, the translator of Ghassan Kanafani’s The Revolution of 1936-1939 in Palestine and an editor at the newly-founded Safarjal Press, the panel drew transatlantic comparisons and touched upon a number of the themes present in the film and their own actions at Kings’ College London, the London School of Economics, Imperial College London and Goldsmiths, University of London.

The year 1968, as an inspiration, was mentioned a few times, albeit without any sense of unquestioning reverence. Jamjoum picked up on the point of the insularity and inherent conservatism of the university institution with the students at the roundtable discussion, who alongside Khalil in the film, appeared to have once shared an illusion. In one of his pieces to camera in The Encampments, Khalil expresses bewilderment as to why a place of higher education like Columbia would involve itself in something as unpleasant as the arms trade. In London, a panel member and student at Imperial College quoted a management figure declaring that “this university is not a democracy, it is a business.”

The Encampments, the film and in real life, are less a story of how institutions went wrong, but one of how institutions were kept right by the side of repression, capital flows, and the ruling class. The Encampments is a strong template for future documentaries that may examine other forms of solidarity actions, which seek to place tangible pressure on the continuation of business as usual, from the dockworkers in various ports refusing to handle military cargo destined for Israel to the Global March to Gaza that set off on a road convoy from Tunisia before it was stopped in Libya and Egypt, miles from the intended destination of the Rafah crossing.

Sheffield DocFest

Documentary film has been one of the more obvious cultural mediums for bearing witness to the crimes against humanity still taking place in occupied Palestine. The films which featured Palestine and the wider SWANA region showcased earlier this year at the Sheffield DocFest were unanimous in their concern with the impact of conflict, resistance, and post-coloniality on everyday human life. Or, to phrase it somewhat differently, the movies were a hard watch. Not so much to be enjoyed, but “appreciated” as one festival staff member put it. The festival took place during the beginning of the missile war between Israel, the US, and Iran. Sheffield is a city with a manufacturing legacy now being put to lethal use; it produces components of US F-35 fighter jets that are sold to Tel Aviv, the same jets that bombed Tehran. It was also the second festival since the unleashing of Israel’s devastating annihilation of Gaza.

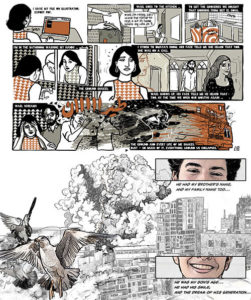

The Palestine Film Institute (PFI) presented projects currently at various stages of the development process. From surrealist narratives of reclaiming history and time to the use of horrifying footage from Israel’s assault on Gaza’s healthcare system, these soon-to-be-finished documentaries challenge the all too one-dimensional portrayal of Palestinians.

During the screening of extracts from Mahmoud Atassi’s White Resistance: Letters to the Living, the crying of numerous viewers was so audible, it almost formed part of the film’s soundtrack. The Syrian-Turkish director, screenwriter, and cinematographer Atassi navigates past and present in the ongoing attempt to release Dr. Hussam Abu Safiya, the director of what was once the Kamal Adwan Hospital in northern Gaza, from captivity by Israeli forces. In the synopsis of the film given to the audience who were watching excerpts, a Palestinian lawyer trawls through footage of desperate operations within the besieged hospital, and discloses the unrelenting commitment of medical staff and ordinary people as the world around them falls apart.

In introducing the film, PFI member and contributor to The Markaz Review, Saeed Taji Farouky said that the inspiration for the PFI came from the Palestine Film Unit (PFU). He insisted, “We must, even in the worst and darkest of times, we must see culture as central to the liberation movement.”

He further referenced the PFU’s own consideration of the work they did “not [as] objective documentarians, not objective journalists but active participants in the liberation of Palestine.”

Away from stage, Farouky is a former spokesperson for the group, Palestine Action. At the time of the Sheffield Film Festival it was not yet proscribed as a terrorist organization by the UK government, despite making headlines following a break-in at RAF Brize Norton, where the group spray-painted two military planes.

Sudan, Remember Us

This was the second year in a row that the Sheffield DocFest Tim Hetherington Award recognized “outstanding humanitarian storytelling” in SWANA filmmaking. Last year’s award went to No Other Land, directed by Basel Adra, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham, and Rachel Szor. This year, in the documentary Sudan, Remember Us, directed by Hind Meddeb, poetry and song meets bullets and tear gas in the streets of Khartoum just as starkly as the past meets the present.

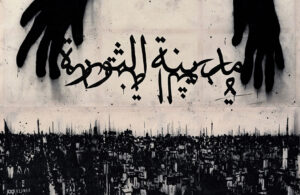

Entitled in Arabic Sudan Y’a Ghali, the documentary takes place during the heady days of 2018 and 2019 where revolutionary upheaval is in the streets and the echo of chants and music populate the air — not only in Sudan, but elsewhere too. Algeria, Lebanon, and Iraq would soon join the forward march of youth demanding change, before being halted by repression, co-option, and ultimately the demobilizing effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

Maddeb, of Maghrebi heritage, published a book recalling her time in Sudan and draws parallels in the film between the slogans and dreams of the women-led rebellion and “my countries’ futures” which she sees embodied within the new generation of activists as they learn from earlier struggles and each other.

In Sudan, Remember Us, a group of activists in their 20s — Shajane, Maha, Muzamil, Khatab, and Chaikhoon — weave through the crowds and spiraling events with an urgent sense of grace and determination that is a testament to the power of an uprising under assault by the proxy forces of counter-revolution. Although aware of its own tragic chronology, the film allows the audience to forget hindsight and share in the activists’ huddled conversations over the aims of the movement and the moments of heartfelt joy, without reeling away from the carnage unleashed by the military establishment.

One of the most arresting scenes is compiled of footage from the June 3 massacre, much of which was shot by the perpetrators themselves, supposedly with the intention of striking horror into the hearts of would-be demonstrators. By re-appropriating this online material, the director and her editor, Gladys Joujou, carry through the subversive spirit of the uprising and lend a certain sense of defiance to the hackneyed narrative of a revolution gone wrong.

We are in dark times, but tomorrow’s dawn can only be held off for so long.

Sudan, Remember Us is a vital watch and its accolades are much-deserved in the goal of ensuring that this forgotten war will not remain that way. It should also be remembered that there is more to Sudan than its capital. Darfur is mentioned briefly by a protestor, but not enough for a film that speaks of a people united amidst the struggle against racism and tribalism. The devastation that Sudan’s periphery has long had to ensure feeds directly into the inter-elite conflict tearing the country apart.

Distributed by Watermelon Pictures — the company behind The Encampments — this production is an ode to those who see a natural bond between politics and the arts, rather than the false dichotomy claimed by those who preach the aesthetics of apolitical neutrality. Maddeb ends the documentary on an unusual note — an original song made for the film as a tribute to the lives lost at the June sit-in, but sung as a classic French chanson. Were the narrative less centered on the power of words and music, it might otherwise have been overlooked.

Gaza Sound Man and a Beirut beauty salon

Another of the festival’s short listed films was Gaza Sound Man (2025), directed by Hosam Abu Dan, an Al Jazeera 360 production that follows sound engineer, Mohammed Yaghi, in an immersive account of the cacophony and chaos of survival in the besieged Gaza Strip. Known in Arabic by the name Gaza, Sound of Life and Death (Gaza, Sawt al-Hayat wa al-Mawt), the film takes on an entire spectrum of audio, from Yaghi’s recordings of the very first moments of a baby’s entrance into the world to the continuous presence of drones and ambulance sirens.

When Yaghi puts on his headphones, it is not to remove himself from those around him but to bring himself closer, even to seek out the voice of a person buried in the ruins of bombed-out buildings. This is a documentary to be watched, not described. It challenges the ability of words to adequately deliver the gut-punch and questions whether audiences can leave the cinema without feeling that their humanity remains trapped beneath the pixelated rubble.

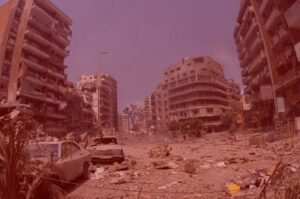

Although it missed out on the Youth Jury award, A Frown Gone Mad (2024), directed by Lebanese artist Omar Mismar, fixates on a single point: a chair in a Beirut beauty salon as clients slide into view to undergo cosmetic treatments. Despite the world outside falling apart in tandem with the decay of the Lebanese state, the documentary locks in on “the desire for security” which is in part what makes it so intimate.

Catherine Huckle, a member of the Youth Jury, went on to add that: “We feel like we are stuck in that room, having a conversation with these people as they try to get what little control they can through these beauty injections.”

Beyond the Arabic-speaking world, audiences at the festival were also reminded of the ongoing situation for women in Afghanistan through the UK premiere of Writing Hawa (2024) directed by Najiba Noori.

In a similar vein to Sudan, Remember Us, Noori’s work is bookended by the twists and turns of political events. The film itself begins with a window shot from a plane soon to be landing in France, in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Kabul in the summer of 2021, as the director goes into exile.

Flashback to the years leading up to the Taliban’s return, Writing Hawa navigates between society’s moving goalposts of what a woman is allowed to do. The director places her own mother, Hawa, in the frame as she slowly steps beyond her traditional lifestyle in an arranged marriage, gets her own business off the ground, and learns how to read and write Dari at the age of 52. Hawa sees her newly rebuilt life dismantled once more as the outside world closes in — on herself, her daughter, and granddaughter, Zahra. Noori — a former video journalist for AFP — makes extensive use of local news coverage and her family’s reaction to geopolitical developments where their lives appear to be no more than an afterthought.

What sets Writing Hawa apart from something like Hollywoodgate is the intimate mother-daughter relation playing out between the subject and the person behind the camera. It speaks to a sense of generational obligation that is reaffirmed when characters like Zahra enter the fray, having initially sought refuge from abusive men only to find extreme patriarchy on the verge of its own reconquista.

Inter-generational relationships are a theme that’s also taken up in A History of Sadness (2024), directed by the Iranian-Canadian director, Layla Tosifi. Over a duration of 18 minutes, Tosifi interrogates motherhood across three generations of women: herself Canadian-born, her mother who left Iran, and her grandmother who remained there.

Dedicated to her grandmother who passed away, the director dives into an archive of family video from the 1990s to catch a glimpse of the unspoken, and often melancholic, tension that lies at the crossroads of culture and tradition. She then threads this together with more recent filming and a series of questions that act as a bridge between the gaps that inhabit even the longest of relationships.

More archival footage

Turning to institutional archives, El Mahdi Lyoubi’s Marseille July 14th (2025) is a delightful experiment in the juxtaposition of time and sound. Taking its cue from July 14, 2019, the nine-minute film captures the day when the Africa Cup of Nations match between Algeria and Nigeria coincided with France’s national holiday. The short ventures out into the streets of the Mediterranean city as celebrations spill over from cafés and cars jam up the roads. Diegetic and non-diegetic sound reach out in compelling ways as a broadcast commentary of the 1974 Bastille Day parade plays out over images of flares, flags, and run-ins with the police. The metropole’s official myths clash with the irrepressible reality of the Republic’s indigenes.

This year’s Sheffield DocFest had been billed as the place “where perspectives meet” — what happens during the encounter itself remains an open question, here at the festival and particularly outside its walls.

These are perilous times, and if the role of the documentary is to document, how are we — those who receive this record — to engage with and respond to it? As spectators, merely to spectate, or is there more to be done even after the credits stop rolling?

From the curtailing of civil liberties in The Encampment to the impunity of violence in Gaza Sound Man and Sudan, Remember Us, the SWANA region may be at the epicenter of any number of the contemporary world’s crises, but it is not unique in experiencing them.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)