TMR’s literary editor works the 2023 London Book Fair.

Malu Halasa

In the Gulf, reading has become the latest hip leisure activity. One of the largest stands at April’s prestigious London Book Fair was the Saudi Commission. There one could spot a man in a starched white thobe and traditional gutrah headdress serving extra-strength qahwa, Arabic coffee. Reading and books were recently taken out of Saudi’s Ministry of Media, and placed at the heart of the country’s 2030 Vision, in the Ministry of Culture. It was significant — an acknowledgement that reading was more than just functional but key to a new sense of Saudi identity. Last year the country hosted four book fairs, including one for international titles in Riyadh, another for Islamic books in Medina and sci-fi and animation in Jeddah, where the K-Pop loving Saudi kids are learning Korean.

Another of the larger commissions from the Gulf at the Book Fair was the Sharjah Book Authority, which had as its calling card thick annual award books. The authority issues these for the Sharjah Children Book Illustration Awards. If they had served strong coffee there, I would have spent an entire day at the stand, lost among the volumes that went as far back as 2017. Sudan was in the news and the drawings and paintings by Sudanese artists such as Islam Zian-Alabdeen, Ahmed Siddig and Tariq Nasre, to name a few, were particularly poignant, considering the ongoing violence in their country.

As the threat of Covid retreats, it seems difficult for the largest English-language publishers to leave the Covid mindset behind. The majority at the London book fair turned inwards and reverted to releasing more and more titles related to living at home, in the West. Well-being is popular. Western houses, apparently, are more worried about sensitivity reading than the state of the world.

There was certainly more promotion of Middle Eastern titles at previous book fairs. Still, interest in the region persists in bandes dessinée, where Books France and the Bureau International de l’Édition Française showcased the latest graphic novels about the region and beyond. From Casablanca, there is colonial and post colonial family memoir, Darna by Zineb Benjelloun (ça et là); history, with Une historie du génocide des Arméniens by Jean-Blaise Djian, Gorune Aprikian and Kyungeun Park (Petit à Petit), and Histoire de Jérusalem by Vincent Lemire and Christopher Gaultier (Les Arènes). The Kurds, too, feature as kolbar porters in Les Oiseaux de papier [The Paper Birds] by Mana Neyestani (ça et là) — reviewed in TMR’s WORK issue by Clive Bell — and as fighters in Jusqu’ à Raqqa – Un combattant français avec les Kurdes contre Daech [To Raqqa: A Frenchman Joins Kurds Fighting Islamic State], by André Hebert and Nicolas Otero (Delcourt).

Mostly, though, the fair emphasized writing about a war not in the Middle East but in Europe — Ukraine. That said, age-old problems like surveillance and terrorism, which people often associate with the MENA region, colored the fair, even though they took place away from bookshelves in liveried and branded cubicles.

British plainclothes police met foreign rights manager Ernest Moret, from the radical French publishing house, La Fabrique, as he stepped off the Eurostar to attend the London Book Fair. Moret was interrogated for six hours, during which he was asked about his attendance at anti-government protests in France. British agents also quizzed him about authors at La Fabrique who were anti-French government. These questions were asked, despite the fact that the UK is no longer a member of the European Union. Moret’s refusal to hand over his passwords to unlock his smartphone and laptop upset UK authorities. He was eventually released sans his devices. “Chilling” was how La Fabrique and the British publisher Verso described Moret’s arrest in a joint statement. But the question remains why British police felt it necessary to act for the French authorities, especially after the UK’s ungracious exit from the European Union. As a headline in the satirical French journal, Le Canard enchaîné, declared: “Tout le monde déteste Scotland Yard” (Everyone hates Scotland Yard.)

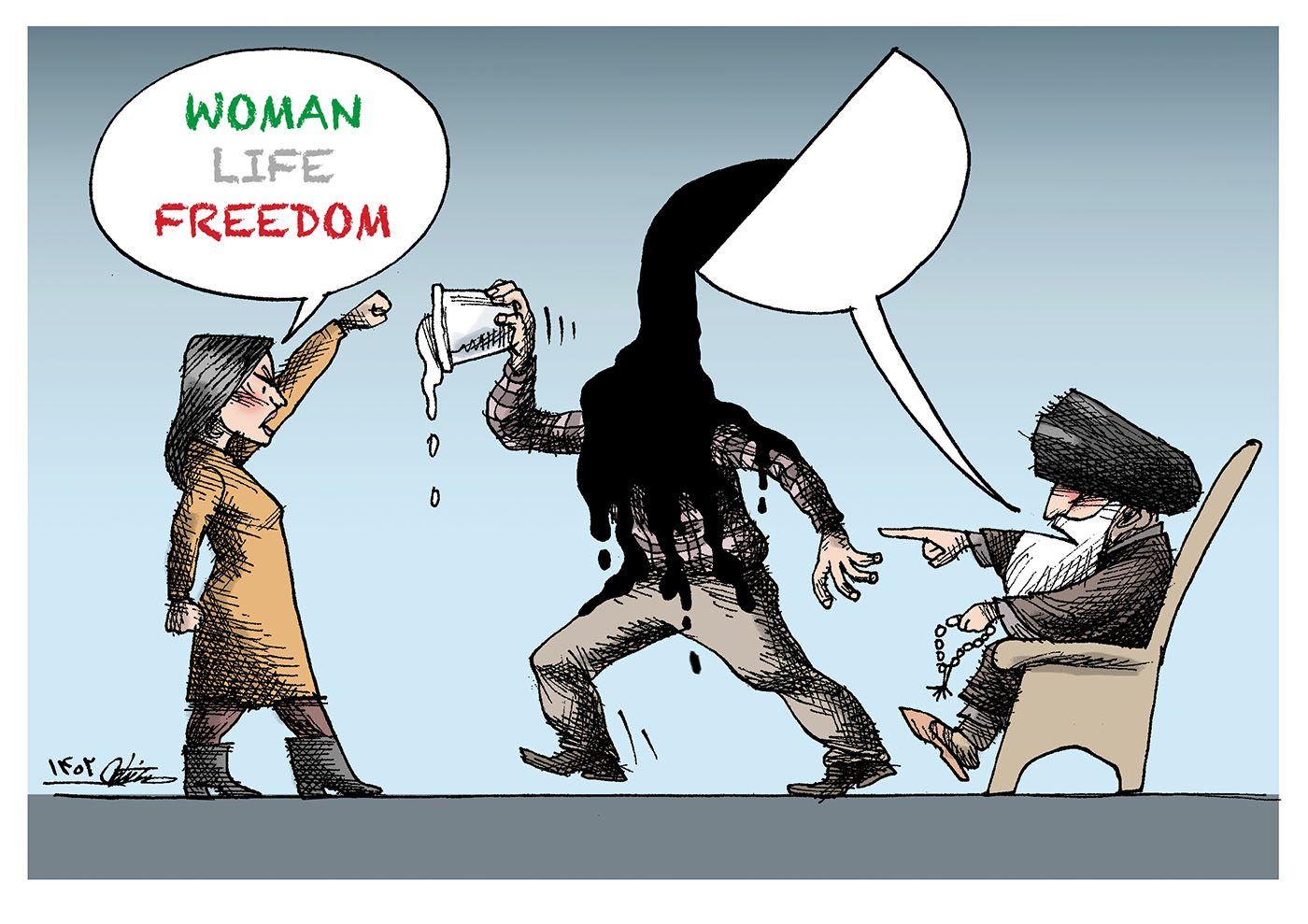

At the fair, Saqi Books announced my forthcoming newly edited anthology, Woman Life Freedom – Voices and Art from the Women’s Protests, in Iran. OneWorld is also publishing a reported account of the Iranian women’s protests by a writer and historian in New York, Iran’s New Revolution by Arash Azizi. On its cover is an illustration of a woman loosely wearing a hijab, fist raised, fighting for what rights, I’m not sure.

My book has a working cover, again an illustration of a young woman, bare-headed, standing on top of a car, with her back towards the viewer, holding a scarf in one hand, and making a peace sign with the other. It is a take on a famous social media image from Jina Mahsa Amini’s hometown of Saqqez, on the 40th-day anniversary of the 22-year old Kurdish Iranian woman’s death. Book lovers purchase books with faces on them. However, in Iran, demonstrating women don’t show their faces, in case the authorities track them down due to the terrible surveillance operating there, and arrest them.

At the London Book Fair, salability trumps all, and rights people prefer selling books to foreign publishers rather than discussing them. This wasn’t the case at W.W. Norton, whose international sales specialists Dina Vakser and Sophie Piquemal spoke enthusiastically about the publisher’s new cookbook, Yogurt & Whey: Recipes of an Iranian Immigrant Life by Homa Dashtaki from the White Moustache, a yogurt company in Red Hook, Brooklyn, New York.

Dashtaki spent her early childhood in Tehran during the Iran-Iraq war, although her Zoroastrian family kept a house in the village of Mobarakeh. They resettled in California and she went on to study law, as good immigrant children do, and became a corporate lawyer in Manhattan. In the 2008 financial crash she lost her job. The death of the uncle who brought her family to the US unmoored her, and she re-connected with her Zoroastrian roots, in Iran. Her famed yogurt company is named after her father’s memorable toolbar white moustache.

More recently, yogurt in Iran has been in the news for all the wrong reasons. A viral video on social media showed two young women waiting to be served in a busy yoghurt shop. A man in a checkered shirt comes in, sees that the women are not wearing hijabs and becomes agitated. He scolds the women — although their exchange is not audible on the shop’s CCTV footage. The women turn away. The man reaches for something off camera and throws pots of yogurt on the heads of the women. The shopkeeper, enraged, comes out from behind the counter, and forcibly pushes the man out onto the street.

In Dashtaki’s family, like mine, yogurt is for eating not throwing. For years a competition existed between my father and uncle over who makes the best lebaneh, or yogurt cheese. Amo Bassam’s is a family favorite because it is light and creamy, whereas my father notoriously tends to squeeze every drop of water out of his made-from-scratch yogurt and the lebaneh he produces is Bedouin-like stiff, hard and perfect for transport across arid landscapes. He is in his nineties and drinks the whey, which Dashtaki maintains is good for you and better than washing it down our sinks into our waterways and streams.

There were some rare taste treats worth teasing out of this year’s London Book Fair.

As soon as I heard of the book Woman. Life. Freedom, ed. Malu Halasa, I rushed to order it. I am European but identify as Human Woman. I followed the events in Iran starting with Mahsa Amini’s murder, in the British media. Reading direct words from some of the women is precious to me. Heartfelt thanks to M. Halasa for this book.