The first Sudanese civil war flickered on and off from 1955 to 1972. A second civil war ignited in 1983 and rumbled into 2005. Now, following last year’s Blue Nile clashes, a new outbreak began in April between government forces, the SAF, and a paramilitary group, the RSF. Other factions have since joined in. Ordinary Sudanese, meanwhile, are leaving, while others are returning to try to save the country.

Dallia Abdel-Moniem

Khartoum works and moves at its own pace. It is a sprawling city made up of the triumvirate of Omdurman, Bahri, and old Khartoum. Each part of the triumvirate has its own unique characteristics; they are separate yet joined at the seams by its inhabitants and the long snaking arm of the Nile River. Omdurman is the original capital, and Khartoum is/was the new one that has expanded with the construction of new neighborhoods. To reach either Omdurman, Bahri or Khartoum we have to cross bridges, such that each is seen as its own city within a city.

My home city is warm and welcoming yet notoriously selfish and harsh, and when temperatures hit the 50 Celsius mark and no shade is found, it can be unforgiving. Deeply misunderstood and unknown by the outside world, if you peel away the layers there is so much depth and the city offers hidden gems. We Sudanese all surged to it, seeking and making a home amongst its broken roads, worn-down infrastructure, and unforgiving temperament. It welcomed millions from myriad backgrounds, those seeking refuge and a better life.

It wasn’t paradise but it was home: a melting pot of people who straddled so many diverse backgrounds — African, Arab, Muslim, Coptic, Christian. A place with dozens of dialects and languages yet metaphorically, we all spoke with one tongue. In Khartoum, Christmas and the Moulid were celebrated with fervor, and church bells and the mosque’s call to prayer both sounded. The city was a party town from December through late January with weddings, events, and religious celebrations. If you weren’t there, you were missing out.

Speak to virtually any Sudanese and he or she will cite fond memories of this city, which is now a war playground for two generals and their merry men.

Every neighborhood in Khartoum tells a story.

El Bashdar stop was where we’d all congregate, and at 1pm sharp the protest would start heading towards the Presidential Palace. Wad Nubawi in Omdurman was where we were chased by security personnel firing tear gas at our protest back in 2018. Burri was our point of entry to the sit-in at the General Command in 2019. Shari’ El Matar was where so many of us celebrated the fall of the dictatorship in 2019.

Having tea at sunset in El Mugran was a must. The confluence of the Blue and the White Niles was a sight to be seen. That precise juncture where the two different colored bodies of water meet is known as “the longest kiss,” with Tuti Island in the background and the architectural dream that is the Nilein Mosque (meaning the two Niles) up ahead. For a short period of time, you were lulled into a sense of security and serenity, two senses that were very hard to come by.

Most nights the air would be filled with the sounds of a wedding celebration, a singer crooning old and new Sudanese songs with ululations ringing out loud and clear. The continuous power cuts made sound travel clearer, though sometimes the generators caused more ruckus. The cafés, from the high-end ones offering fancy pastries to those that grew out of a tea lady’s stall where everything from sweet tea, cardamon, and ginger-flavored coffee to freshly fried lugaimat sprinkled with powder sugar were served from sunrise until the late hours of the night, was where we met, talked, planned, laughed, and bemoaned the state of our country. The conversations were free-flowing and most times you’d bump into someone you knew or would forge new relationships and contacts.

I had the best barbequed meat in my life at Kandahar, a livestock market well beyond the city’s boundaries. When I queried why it was called that, I was asked where Kandahar is located. “Afghanistan,” I replied. “Exactly; it’s so far away from Khartoum and so is this place,” came the explanation. The ground was sprayed with water to make it cooler; beds and benches were laid out for the ubiquitous post-food coma, and the meat was slow-grilled as our stomachs grumbled, demanding to be fed. Camel liver was marinated in lime, chili, salt, and pepper, and served as a delicious appetizer. Our grilled beef was served with freshly baked baladi bread, a garden salad, pan fried sheep liver and kidneys in a garlicky sauce, our infamous dakwa (peanut butter) salad dip, and a shatta (chili dip) so fiery it stops just short of being inedible. It’s where we plotted our next moves to bring about change to our country. Food and conversations — the best combo. The ideas flowed.

The souqs of Omdurman, El Markazi, El Shaabi, and Saad Gishra were where you found anything you could think of, from the freshest produce to household items, knick knacks, fashion fabrics, and accessories. Souq Omdurman especially was something special and unique, the oldest and largest market. The best spices were found there, their pungent smells sending you into a sneezing fit while the shopkeepers laughingly teased you for being so “delicate.” The alleyways were lined with shops selling Sudanese ornaments, from ebony figurines and carpets from the Rashaida tribe in Eastern Sudan to the straw baskets and old-school household items that every Sudanese home had at one point in time — star motif-painted steel bowls and platters, the coffee gabana and cups, the woven taraqa used to cover the food tray. Every time I went, I discovered a new shop, a new alleyway filled with goodies; you never left Souq Omdurman empty-handed. But Souq Omdurman is no more. It was burned down and looted during the ongoing war.

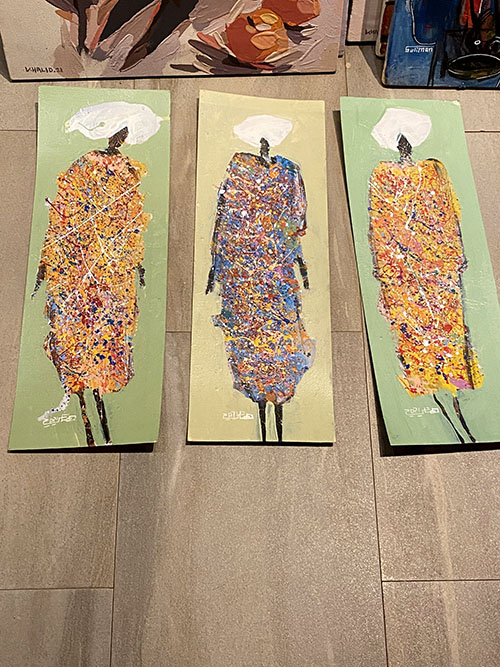

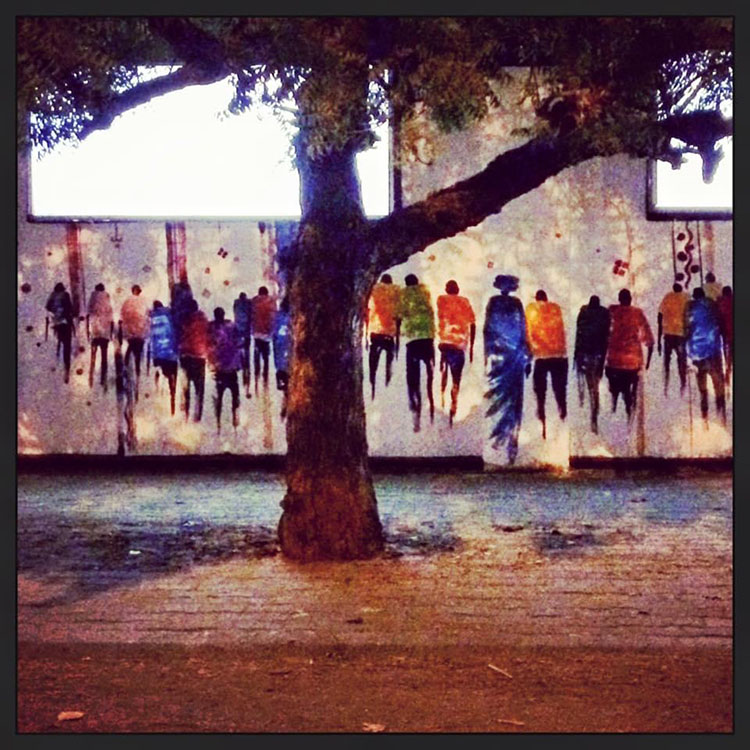

Back in the days of promise, when the air was electric with change, a favorite pastime of mine was to go on an art jaunt. The art scene in Sudan had taken a huge leap in the ten years since I moved back home, in 2013. Whereas earlier there were a few established names, now there was a younger, hungrier, and — dare I say — more expressive generation of artists who emerged and were making a name for themselves. I guess repression does bring out creativity in people. Using various formats, from canvases and graphic design to fashion, music, and film, Sudanese creatives were finding new ways to tell their stories. Screenings were put on for Sudanese films and documentaries, and exhibitions were held to showcase the best and the up and coming in the world of art, sculpture, and design. Jewelry designers mixed the traditional with the contemporary. The radio airwaves were filled with the sounds of a new wave of musicians who mixed the classics with their own original pieces, seamlessly weaving in AfroBeats as well as lyrical hip hop in both Arabic and English.

And those of us who could lapped it all up. We bought into this new frenzy of creativity. We were investing in the present and in the future, in fellow Sudanese who dared to dream of something better, who told our stories in the best way possible.

Today, those of us still back home, who couldn’t and haven’t left, can’t keep holding down the fort for much longer. The civilian-led groups and committees have always without fail stepped in when needed and now, when the state structures in the capital have completely collapsed, they are doing jobs many can’t fathom in the most trying of circumstances. They set up communal food kitchens, find and provide refuge to those escaping the raging war, serve as a medical care system, and help bury the dead when their families can’t. These young Sudanese are our beacon of hope, and we are all forever indebted to them. But a tired and exhausted Khartoum can only offer so much. It gave us a lot, but it also took a lot from us.

Nevertheless, we must start again. In the past, try as many of us did, we couldn’t leave Khartoum permanently; we always rushed back to her. We came back with plans, with ideas, with the belief that this time round we would make it better. And we did for a short while. Well, we will have to do something similar again: rebuild, replan, re-live. When? No one knows. But soon, I hope. I miss my Khartoum, our Khartoum.

Thank you Dallia. This moved me deeply. We were lucky to know and grow in a Khartoum that provided us with great opportunities and values, and a sudaneya identity which we will carry with us wherever we go. We must hold onto that, and continue our journey by enlightening ourselves and others. You are succeeding in doing this, in spite of all you have lost. Clearly you are and will gain a lot inshallah.