Kurdish female and non-binary writers strive to communicate Kurdish women’s unique experience of patriarchy, suffering and state violence to the world, while simultaneously resisting the potential constraints imposed by this political task. At its best, the new anthology showcases writers pushing boundaries and subverting political expectations, achieving its mission statement of “breaking… monolithic ideologies about the Kurds.”

Sleeping in the Courtyard: Contemporary Kurdish Writers in Diaspora, edited by Holly Mason Badra

University of Arkansas Press, 2025

ISBN 978-1-68226-273-3

An important new anthology of work by contemporary female and non-binary Kurdish writers aims to challenge the reduction of Kurdish women’s experience to a bleak political struggle, expressing (in the words of editor Holly Mason Badra) not just “what we are without… there is great bounty, too.” Yet that ‘without’ necessarily hangs over Sleeping in the Courtyard: Contemporary Kurdish Writers in Diaspora, as contributors strive to communicate Kurdish women’s unique experience of patriarchy, suffering and state violence to the world, while simultaneously resisting the potential constraints imposed by this political task. At its best, the collection showcases writers pushing boundaries and subverting political expectations, achieving Badra’s mission statement of “breaking… monolithic ideologies about the Kurds.”

Unavoidably, the anthology opens with a summary of the political violence faced by around forty million Kurds, whose homeland remains occupied and divided between modern-day Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria. Even as they suffer patriarchal discrimination and marginalization, Kurdish women have played an especially prominent role in the region’s ongoing struggle for self-determination and democratic rights. Yet it is for this very reason that female Kurdish writers feel tasked with conveying overtly political messages to their readers, to the potential exclusion of other, less straightforward approaches.

Of the mere eleven contemporary Kurdish female writers listed on Wikipedia, for example, only two are principally known for literary work. Most are journalists, lawyers, or campaigners. Two have been tortured and three jailed for their writing and political activity in Kurdistan. Likewise, one contributor to Sleeping In The Courtyard (Meral Şimşek) was sentenced to jail in Turkey for writing a sci-fi story, while another (Maha Hassan) was banned from publishing her “morally condemnable” work in Syria. In the context of what Badra calls “linguicide” and the continued repression of Kurdish language and culture, it’s therefore understandable eight of the nine books Badra suggests as further reading on Kurdish women’s experience are political texts or first-person testimony, rather than literary works.

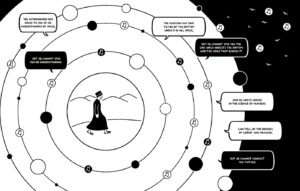

Hence the importance of the new anthology, which mixes poetry, fiction, first-person essays, and an excerpt from a graphic novel. Yet tellingly, it’s not always immediately obvious whether a given contribution is fiction or memoir. Like many female writers from marginalized communities, these authors must reckon with the potentially unwanted imposition of autobiographical readings on their art.

Some writers meet the challenges head-on, offering directly political treatments of war, exile and womanhood. The extract from Daughters of Smoke and Fire, by leading contemporary Kurdish novelist Ava Homa, is typical in this respect. As soon as Halabja is mentioned, the informed reader knows with grim certainty that we will soon be reading about the chemical weapons massacre that took place in that Kurdish town during Saddam Hussein’s 1980s genocide of the Iraqi Kurds. As soon as butterflies are mentioned, we know we will turn the page and read they are gassed to death. And so it goes. But conversely, when we read of a Kurdish mother teaching her daughter the alphabet, we know A will stand for “Azadi,” or freedom. “The heads of all those Kurds crushed beneath tanks” are directly linked to the narrator’s “overpowering urge to scream my story,” in stark, black-and-white response, creating a literary responsibility that cannot be avoided.

The same direct, unadorned approach is elsewhere deployed to reflect Kurdish women’s experience in the diaspora, as when Cklara Moradian reflects on the “the loss of language, the humiliation of assimilation, the rejection of my queer body,” linking a traumatic childbirth to the Kurdish history of genocide. This style can be powerful, but it also rubs up against its own limits. Syrian-Kurdish novelist Maha Hassan’s reflections from a year-long residency in Anne Frank’s house have undeniable worth in challenging stereotypes and preconceptions around Middle Eastern writing. But the subsequent stark, polemic addresses can fall rather flat, as when Hassan directly addresses Frank: “we exist here together — culturally separate, but alike. Your life’s most consistent theme was flight. Mine’s the same.” When Hassan expresses her people’s contemporary suffering in direct comparison to “the Jewish girl, who knows nothing about Arabs and Kurds and Muslims and countries where women are oppressed and killed,” the complex particularities of these two experiences are washed away.

Other writers take a contrasting approach, adopting the imagistic and intensely personal lyric style associated with contemporary women’s and queer diaspora poetry. Badra’s own poems are one example, as are Leila Lois’ verses in which “honey-drenched, rose-scented/stories run through my mind like sepia.” Amid the barrage of newspaper headline horrors, these moments offer a sense of refuge, as writers tentatively explore the “bounty” of traditional Kurdish culture. Multiple authors drop a Kurdish aphorism into a story directly followed by its English translation, a convention expressing a seriously felt duty to translate Kurdishness to a global audience. Yet this bounty, too, is contextualized by loss, a sense that “no new experience could match… those days, nothing was as rich in color, taste and smell as the memories of that poor life,” as Choman Hardi describes the numbing experience of exile.

Other contributors step beyond both of these more familiar, and potentially “monolithic,” approaches. Emerging writers explore and make a virtue of the potential dissonance between and insufficiency of familiar tropes, political rhetoric, and received narratives of women’s diverse experiences. Even as they might undertake the same literary tasks of communicating Kurdish suffering and celebrating Kurdish womanhood, these contributors are alert to the complex interrelation and clashes between diaspora and domestic experience, womanhood and Kurdishness, literary convention and mundane experience.

Tracy Fuad’s self-reflexively subversive poetry is a stand-out example. As in her Object Exercise, Fuad sets out to challenge Kurds’ long-term status as the mute subjects of media discourse, while simultaneously acknowledging the real-world impact of this unwanted status. Fuad achieves this with sharp, playful, deliberately bathetic references — Googling the Turkish-occupied Kurdish region of Afrin only to throw up images of Afrin Nasal Spray, listening to “two German women sing flat English” over beats sampled from un-named Kurdish musicians — that acknowledge the complex and disorientating conjunctures of identity in a politicized diaspora, while eschewing both political sloganeering and lyrical cliché. The same sharp yet disorientating effect is on display when bestselling disapora writer Gian Sardar shows us an American woman observing her Kurdish partner struggling with trauma, photographing his private moments of grief using insights he himself has shared. There are no simple answers or monolithic experiences here.

There’s perhaps a sense in which this approach is most open to English-language writers in the diaspora, and thus especially appealing to Anglosphere readers (like myself) who know the Kurdish experience from a sympathetic but ultimately external perspective. These potential tensions are animated in the dialogue between Meryem Rabia Uzumcu and her mother, in which the young writer speaks expressively, fondly and at length of her diaspora childhood, while her mother recalls the same experiences in basic, limited terms as a “kind of prison.”

But this assessment shouldn’t imply a value judgement, separating enfant terrible voices in the diaspora from more conventional narratives of Kurdish womanhood. Rather, the anthology makes it clear that Kurdish women’s experience has always been marked by a salty pragmatism inspired by repeated clashes with patriarchy and state power. This tart and practical wisdom is not the preserve of internet-literate Anglosphere poets, but already present in the historic Kurdish poem cited by Ava Homa, where a crow advises an eagle, “settle for flying low and feeding on debris.” More generally, contributors working in Kurdish or still living in Kurdistan achieve the same subtle troubling of conventional images, as in Narin Rostam’s blackly comic tableau of domestic violence and TV wrestling, or Nahid Arjouni’s exasperated appeal to the malevolent incarnation of her depression: “dear God, please pick up your feet/I want to scrub the floor.”

Kurdish experiences and identities are always “hyphenated,” in Badra’s terms, double “exiled” as stateless women even if they never leave Kurdistan. They thus offer a unique tool for exploring the endlessly complex refractions of identity — not least by turning the lens back on (Kurdish) men. Is Sardar’s male lead repressing his grief because he’s a stoic Kurd, because he’s an emotionally unavailable man, or both? Is Hardi’s protagonist unable to recapture the intense sensations of childhood due to the trauma of exile, or simply because this is what happens as one ages?

The specifics of Kurdish women’s suffering necessarily remain a more or less explicit theme in all the anthologized work. But there’s also a growing sense that despite this incommensurability, the Kurdish experience has something more to offer: that what Sardar calls the “distance of separation” between nations, generations, and identities can prove the starting point for mutual illumination and understanding. As in Uzumcu’s intergenerational dialogue, we may struggle to understand one another’s experiences, but it is through this struggle that we can reach a new, mutual comprehension.

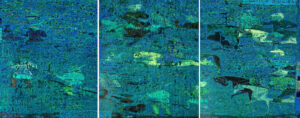

Thanks to the vital and generous effort of figures like Badra, the Kurdish literary sphere continues to grow and diversify. In the hands of talented young writers like those anthologized here, the Kurdish experience is becoming not only an object of journalistic and academic study, but also a lens suitable for understanding the world we all live in. It’s perhaps telling that Moradian’s initially intensely personal reflections on personal suffering and historic trauma expand outward, to find solace through meditation on the broader historic and artistic significance of the color blue — in unstated opposition to the red, green, and yellow which traditionally represent Kurdish culture. “I stopped being preoccupied with the “Kurdish question, the question of identity,” she writes. “Blue was the last color to arrive. With it… came freedom.”