In the heartland of Anatolia, a contemporary art show featuring seven artists, including its curator SaraNoa Mark, at the largest Seljuk caravanserai on the Silk Road, changed one foreign art writer’s sense of direction in Turkey.

Matt Hanson

As the last light of the Turkish summer fell from the Anatolian horizon in late September, last year, I accepted an invitation from American curator and artist SaraNoa Mark to visit their show at Sultan Han. I’d gained a certain local reputation as a foreign art writer, and Mark’s vision, as a young internationalist eager to puncture the art world bubble, was enticing in its brazen, experimental ambition.

Without the backing of a publication or institution, as a pure freelancer, I went, free of parameters and critical designs, to simply see what was in the province of Aksaray, out in the high plains between Ankara and Konya.

The idea was to venture as far afield as possible, not only across the map, but in terms of conceptual order, to contemplate the range of human expression as its distended extremities reached out to include the isolated and remote.

Once beyond Istanbul’s sprawl, leaving tens of millions to its concrete squares, the eyesore of a cityscape fading, I drove alone over the high, rolling, wheat-hued hills of the Anatolian plains, as shepherds dotted vistas that had long captivated the imperialist ancients. Asia Minor’s tectonic unity is a continent between continents, merging histories with myths where, despite coming together, East and West do not just meet, they steal each other’s identities.

Night fell on a single-lane road alongside the salt flats by Lake Tuz. I had visions of camels leading medieval caravans from Central Asia over its desert-like arid environs. In past centuries, Silk Road merchants with Turkic tongues, Uighur and Kazakh, Kyrgyz and Uzbek, had all stopped here, ushered in by the first Turks to rule in Anatolia, the Persian-influenced Seljuks.

Temporal and spatial disconnections racked Carved Conversations, a show of site-specific, historical sympathy curated by Mark, a sketch and installation artist who received Fulbright support to pursue their crafts in Turkey (the other artists in the show included Alejandro Díaz‑Perera, Buşra Tunç, Cara Megan Lewis, Lara Ögel, LÜTFÜ, and Nergiz Yeşil). In the Anatolian town “Sultanhanı,” named after Turkey’s largest preserved Seljuk caravanserai, “Sultan Han” is a touristic landmark of glaring proportions, dwarfing the local village of rug-weavers, hoteliers, and farmers. Its appearance resembles the surrounding semi-arid plains of the Lake Tuz region — except there are no more Silk Road camel riders, just rural truckers and unemployed youth who inhabit Turkey’s impoverished, conservative heartland.

For me, someone raised in rural small-town America, the dusty alleyways of Sultanhanı conjured reminiscences of my roots, countrified and rough-and-tumble. The nasal bursts of the double-reeded zurna and roar of davul bass drums rocked from car speakers and community centers, as musicians and speakers fought amid the otherwise deeply silent ambiance, where low buildings met sheer sky, unmediated by urban complexity. Having gone so far, I was, curiously, closer to home.

The signs of fall were nascent when I stepped into the central court of Sultan Han and its adjacent rooms, accented by curatorial interventions mounted by Mark, who placed their own artwork, Yazılıkaya (2022), in the middle of the 13th-century edifice. The piece, translating from Turkish as “Written Stone,” is a series of engravings, or carvings, in stone relief, installed on the steps of the central kiosk-mosque of Sultan Han, forming a pyramid of building blocks against the anterior of the structure-within-the-structure. It is integrated seamlessly with the overarching historical aesthetic, and converses with the material dialectics of the indigenous architecture through correspondent patterning.

Teasing out common threads between, on the one hand, visual motifs conceived by the Persian-inspired Turkic architects, engravers, and calligraphers of old, and, on the other, the newfangled and globalized vocabularies of the contemporary art world, Mark ambitiously sought to bridge that yawning abyss of time and space.

Yazılıkaya was a clever and studied feat of localized site-specificity, assimilated into Sultan Han’s ancient designs. (Without a map or placards, the artwork is practically invisible against the stunning internal facade.) Mark affixed the 23 concrete panels, inventively impressed with geometries and motifs that bear striking resemblances to medieval Seljuk design. The outwardly facing surfaces of a triangular stone stairway lead up to the window-like entrance of the building within the building where worshippers prayed. As the earliest Turkic dynasty to accept Islam, the Seljuk universe is studded with a tapestry of multicultural fragments gleaned from across the old caravan routes of Central Asia in such cities as Konya or Mardin, where competing Turkic sovereignties like the Artuqids were famed for building intricately carved stone structures across Anatolia.

Carved Conversations’s stone engraving seems intended as a metaphor for collective memory. As its centerpiece, Mark’s series of clay etchings were semi-abstract, reminiscent of aerial premodern urban topography and geological formations about the ancient world, visionary semblances of regional architecture as seen from above, within, and up close. Altering their perspective, and musing on land art and such iconic reliefs as the concave, quarter oval network of “muqarnas” sculptures that glorify the gates of Sultan Han, Mark demonstrated a keen eye for the limits and developments of international contemporaneity in contrast to traditionalist, non-Western aesthetics. In search of a shared ground on which to create and appreciate postmodern art that encompasses the depths and reaches of the world’s tangible heritage, beyond the conventions of classical training, Mark is the kind of contemporary artist who produces work in dialogue with the range of human creativity throughout time.

Carved Conversations tested the boundaries of off-site remoteness, challenging geographical and aesthetic approachability. Sultan Han is constantly busy with the foot traffic of travelers in from long bus rides and packed tour itineraries. Without prior knowledge of its themes of aesthetic and conceptual dialogue between premodern and contemporary art, casual sightseeing overlooks Mark’s curatorial nuances. The absence of its storied drifts and the obsolescence of its role as one of the most glorified of stopovers from Xinjiang to Halicarnassus beside found objects, AI-rendered paintings, abstract installations, and a video performance ran the risk of alienating public viewers.

In their art and curation, Mark has attempted to turn ancient stone into an allegory for interpersonal communication. Carved Conversations is steeped in the philosophical ideologies of its artists’ modernist mentalities, which tend to endow seemingly self-referential notions with universal, almost imperial presumptions. The work of Cara Megan Lewis is a case in point, as her trio of pieces titled “The Water Shed” (2022) is born of issues that are uniquely important to Hahamongna territory in what is now Altadena, California. In three rooms thought to be Sultan Han’s hamam, or bathhouse, Lewis mused on the drying of the Hahamonga valley, a reality that starkly contrasts with its indigenous name in the Tongva language, signifying a flowing and fruitful ecology. The gravity of found objects emerging from a dried riverbed, since transformed by settlers who came with their own naming traditions, technologies and cultures, is part of her parallel, in-situ intervention into the layered temporal distinctions of Sultan Han.

Carved Conversations experimented with the potential of shaped stone as a linguistic vessel, carrying the signs and traces of human contact across millennia and hemispheres.

Placed in the chamber nearest to the main front gate of Sultan Han, Lewis’s works were exhibited beside those of Alejandro Figueredo Díaz-Perera, whose digital painting series “Protomother” (2022) is the result of a technological innovation in which an AI generator makes images based on simple texts. The absurdity of potatoes suspended at the end of twisted wire, along with a pyramid of tennis balls and discolored algae sheets had a disorienting effect within the overall ambiance of one of Turkey’s grandest landmarks. The dystopian evocation of lost space and passed time as phenomena of mutual dependence is all the clearer in Lewis’s work when set beside Díaz-Perera’s painting, whose title (“Protomother”) and content are derived from the meaning of the word “Anatolia,” which might be translated from Turkish as “mother-full.”

The pixelated canvases of Díaz-Perera leaned haphazardly against the rough, aged rock of the eerie room’s walls. The place sheltered travelers and pilgrims from across Eurasia free of charge for up to three nights. Carved Conversations threatened to cancel out the innate and well-preserved aura of the caravanserai and the intended meaning of the contemporary artwork, as they were so starkly opposed, their single source of inspiration dissolved by an order of object-oriented displacement, deemphasizing the Benjaminian aura, or sheer presence of the medieval features, and in their stead posing a slapdash juxtaposition of spontaneous surreality and cognitive dissonance.

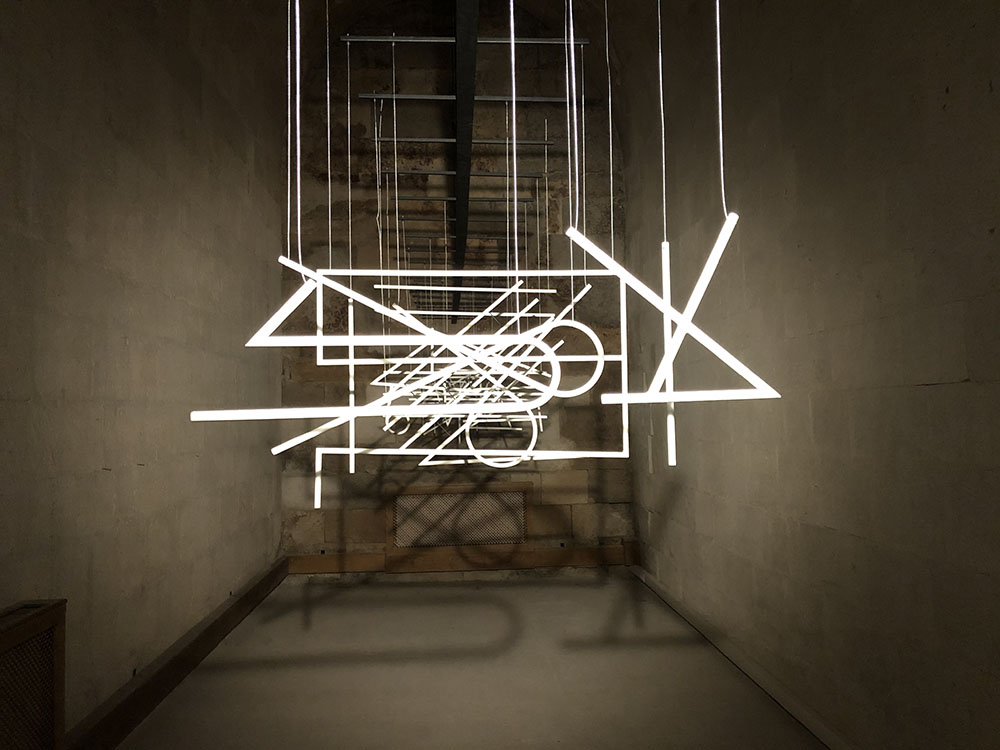

Moving closer to a spacious, grandiose domed hall hosting municipal exhibitions on topics like the diversity of woven carpet styles and the Armenian poet Sayat Nova, I found the other chamber installations increasingly inventive. Behind the darkness of a curtain in the cold cell, a work of metal sculpture and lighting design by Buşra Tunç entitled “Scratch” (2022), placed a number of suspending, calligraphic forms made with white bars, simply designed, like letters, asemic in their abstraction. As a projected light illumined the air with a fresh articulation of overlapping linguistic shapes, the artist’s vocabulary confronted the presence of mysterious engravings that continue to baffle archaeologists and historians throughout Sultan Han. The piece was harmoniously aligned with Mark’s and evoked the traces of extinct languages and bygone cultures housed within the rectangular enigmas of the caravanserai.

“Turquoise II” (2015), a video by Lara Ögel, showed the hypnotic repetition of turquoise worry beads fingered by a hand tattooed with a hamza evil eye. The work fit into the space like a key in the right lock. And set in the corner of a storage room, the ambiance of the piece transformed into the detail of its subject, a Seljuk woman, kneeling down, out of sight, biding her time as she waited. “Turquoise II” was an apt symbol for the Silk Road, when seen from the vantage point of Sultan Han, its endlessly cyclical interconnectedness joined by caravansaries that, like the beads of a rosary, were linked by the narrow, now almost invisible trails of story, song, architecture, and art.

Ultimately, like a tarnished and cracked mirror, Sultan Han is a space where the global public might have something approximating contact with an age when people moved more slowly over the Earth, when the lines that now define borders and cultures moved and blurred. Carved Conversations experimented with the potential of shaped stone as a linguistic vessel, carrying the signs and traces of human contact across millennia and hemispheres. By adapting the antique caravanserai for the purposes of new art, Mark encouraged an interactive and decidedly postmodern appreciation of Sultan Han, one that might well apply to other premodern landmarks.