A novelist and poet from flood-devastated Derna, often called Libya’s “city of poets,” has devoted her most recent book to the city of her childhood and adolescence.

Naima Morelli

“Oh my God, how did I write about all my love for my Derna, and not realize I was writing her elegies?” wrote Libyan novelist Mahbuba Khalifa on the 28th of September, after she learned about the floods that nearly wiped out the city.

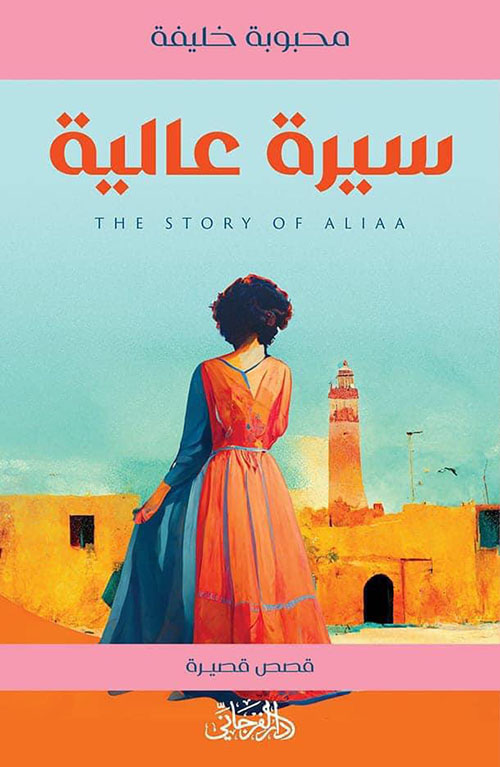

A writer, poet and prominent literary presence on the Libyan cultural scene, Khalifa recently published a collection of stories about her hometown of Derna entitled The Story of Aliaa. One of these stories, “The Valley Came,” happens to be about the catastrophic Derna floods in 1959, and so felt tragically prophetic to her and her Libyan readers.

A writer, poet and prominent literary presence on the Libyan cultural scene, Khalifa recently published a collection of stories about her hometown of Derna entitled The Story of Aliaa. One of these stories, “The Valley Came,” happens to be about the catastrophic Derna floods in 1959, and so felt tragically prophetic to her and her Libyan readers.

Born and bred in Derna, Khalifa was introduced to literature by an uncle working at the local public library back in the 1960s. She left when she was just 18 years old to study philosophy at the University of Tripoli, but never severed emotional ties to her hometown.

Later, she was forced to leave Libya altogether: her articles in opposition newspapers, as well as the political leanings of her husband, politician and lawyer Goma Attaiga — an opponent of the Ghaddafi regime — meant that the entire family had to flee the country.

In the nomadic life she has led ever since, she returned to Derna again and again in her writing, turning it into a place of the soul. “People always told me I am a bit obsessed with Derna,” she tells me at the beginning of our conversation.

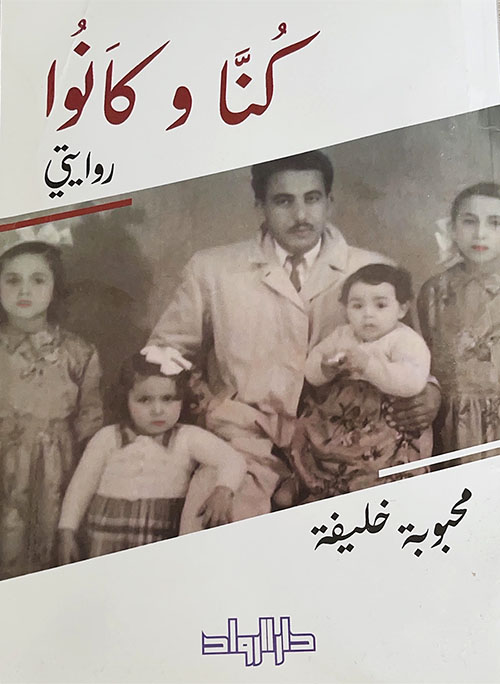

Your first novel, published in 2015, is called We Were & They Were. What convinced you to adopt the form of the memoir?

For my first novel, I had a strong desire to give a testimony of the life of a Libyan woman who lived through a certain stage in the history of her country and was affected on a personal level by some significant events. Also, as I shared poems, texts, memories, and writing on my Facebook page, I received many requests from family and friends to narrate part of my biography and life experiences as a memoir.

My generation was an eyewitness to many confusing changes for us Libyans, who, before that, were living fairly calm lives. My entry to the university coincided with Ghaddafi’s coup against the monarchy, resulting in a period of drastic transformations. Oil had only been recently discovered in Libya, and the country was awash with the hope of a prosperous future. All this quickly turned into a life of anxiety and fear of the new authority, and the beginning of arrests and restrictions of liberties. We had huge economic and social changes that took place after that, which had a negative impact on most Libyans. My husband was arrested, and this of course affected my own life greatly.

Your first novel touched briefly on some details of your childhood in Derna. But it is with your latest book, The Story of Aliaa that the city really takes over, becoming the real protagonist. Did you feel the need to share more about your hometown after publishing We Were & They Were?

I started to write The Story of Aliaa in 2020. It’s easier for me to write short stories than a novel, and I’d already shared small snippets, memories, and pieces of writing about Derna on my Facebook page. In the book, I’m writing about the city over the years, and I tried to intermingle historical facts, reconstructions, and personal memories to create a fiction that makes the city come alive. I tried to chronicle the city’s legacy, its neighborhoods, the small details, and those who live in it. I believe the artistic side of Derna goes hand in hand with its rebellious soul. Of the 35 short stories in The Story of Aliaa, 21 are set in Derna, and in the remaining others, all the different protagonists live with constant memories of their hometown.

The first story I started working on is the title one, that of Aliaa. There is a saying that you cannot emerge from your own skin. You have to put all of yourself on the page when you write, and I’m drawing so much from my own life to write about Aliaa and her travels. I wanted the character to take the reader on a journey from Derna to the far south, ending in Tripoli. Aliaa is a rebellious soul, and in this sense, she’s personifying Derna. She needs to travel far away into the country to find passion and fulfilment, but she always carries Derna in her heart.

Although each story has a different protagonist, Aliaa stayed with me long after finishing the collection, and I kept writing her story, turning it into a long-form novel in eight chapters, where she is the sole protagonist. In that upcoming book, Aliaa will cross different decades, and while she evolves, the historical and social context around her changes as well.

Within the collection, the harrowing “The Valley Came,” details the story of the floods of 1959 from a first-person point of view. How did you navigate historical research and imaginative reconstruction?

This story was entirely based on historical research about the 1959 flood. I tried to put myself in the shoes of someone who experienced that event, although I didn’t personally witness it. It wasn’t very well documented at the time, and as the older generation is passing away, this event is slowly being forgotten. Most Libyans actually learned about the ’59 floods only when the recent floods happened, which is quite incredible.

For me, the ’59 floods were a haunting topic. I ended up mentioning them also in another story called “Marianna Latsi,” which tells about the valley’s floods, as well as the story of the pilgrims and a Greek ship called Marianna Latsi.

In the book there are tragic moments, but most stories are rather joyful, hopeful, and full of light and irony. I’m thinking about one called “My Aunt and Churchill.”

This is a tale about the “Darnawi” aunt, and characters like her, who represent a sort of prestige, and around whom the whole family gathers. The aunt is upset when she finds out that one of the women in the family has compared her to Churchill.

I usually draw from memory, intermingling it with what I learn from research. I tend to have a visual memory, which provides me with images and ideas to develop my narratives. Some of my stories were inspired by my constant moving from one place to another, whether inside Libya or abroad.

Another story I have in the book which is about the pure joy of the old Darnawi days is “A Beautiful Girl Walking Elegantly.” It is about an endurance test that takes place between a dancer, a flute player and a drummer.

Your novels have a distinct female gaze. Do you think that women writers have a fresh and different point of view on Libyan history as compared to men for example?

We have many historical novels written by Libyan writers, men and women. I think every piece of literature has some reference to history in it. So a literary work is usually not without reference to the history of the events within the text and its direct impact on the form of the narrative and content.

There are many Libyan women writers of whom I’m undoubtedly very proud. I will mention some of them, and I apologize for not mentioning everyone, and I have to emphasize that they are all pioneers and influencers of the Libyan cultural scene; Zaema Al Barouni, Mardia Al Naas, Azza Al Maghour, Razan Naim Al Moghrabi, Aisha Al Asfar, Aisha Ibrahim, Fatima Al Hajji, Sharifa Al Giadi, Lotfia Gabaili and many more.

Now you’re working on a new book project, and it’s again a historical novel.

My new book will be called A Sleepless Night in Tripoli, and it’s set during the conflict between the Allies and the Axis. It’s about those people who took to the caves in the mountains surrounding Derna to shelter from the aerial bombardment to which all the Libyan coastal cities were subjected. Most of the story happens inside one of these caves, when a boy and a girl meet while sheltering from the shelling, and the story unfolds from there. Because of everything that has happened lately, I’m not working on it at this very moment, but I will resume writing soon.

Right now, you are using social media to share beautiful elegies for the people that you lost in the flood. What do you think is the power of literature in such trying times?

Yes, I post every single day, something for a specific person that we lost. I want their personality to be remembered and to keep them alive. I want to celebrate their lives and remember how great they were. Rather than sharing simple Facebook posts, I wanted to work on each text with the same care, the same attention and craft as if I were writing a book, and indeed I might collect all the elegies in a book in the future.

I aim to bring some comfort to those who have lost someone. Most Libyans have been affected in one way or another. I want them to feel this sense of beauty that still coexists with this incommensurable loss. It’s also therapeutic for me. As I remember these people and share about them, I feel that no one I loved is ever truly lost.