The Book of Redacted Paintings is a debut collection by Arthur Kayzakian that uses a medley of poetry, correspondence, and prose, challenging genre categorization while maintaining novelistic breadth.

The Book of Redacted Paintings, by Arthur Kayzakian

Black Lawrence Press 2023

ISBN 9781625570512

Sean Casey

Near the beginning of The Book of Redacted Paintings is a letter. Its author, whose name is redacted, tells the story of a painting, “My Father under the Stars,” a rendering of a photograph of the nameless author’s father taken just before the Iranian Revolution. The redacted writer’s mother commissioned the painting in London where the family took refuge following the Revolution. The father remained behind in Iran, but the painting powerfully conveys his presence:

We hung the portrait on the wall in our den; it was there when guests arrived. My father’s countenance was so massive that the guests felt he could leap out of the painting and reach for the half-eaten baguet held in their hands. “He looks so real,” they would say. The painting was hung there for years. We brought the painting to America when we migrated …

The painting, we learn, has been stolen.

The Book of Redacted Paintings, the remarkable debut collection by Arthur Kayzakian, tells the story of this painting, its theft, its absence, and attempts at its recovery. It does so in a medley of poetry, correspondence, and prose — one that challenges genre categorization while maintaining novelistic breadth. As the collection and its plot develops, the lost painting grows in resonance as a symbol of a more profound loss: that experienced by displaced populations. The painting’s predicament speaks to the displacement of two diasporan populations: Iranians who fled during the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and Armenians who escaped 1915’s Genocide in the Ottoman Empire. It also speaks to the absence of those who did not escape. In “Galaxies,” one of the book’s finest poems, an unnamed soldier recites a poem on Iranian television. The poet, of Iranian and Armenian ancestry, invokes the duduk, the Armenian double-reed woodwind instrument:

can you hear the desperation in my joy of living the sound of a duduk

carries enough ecstasy to sadden the trees blowing sand over the graves of

my scratched-out ancestors This is why I will light houses on fire I am a

flower with the register of exile ready to exonerate my war dance

Scratched-out ancestors. People can be redacted too.

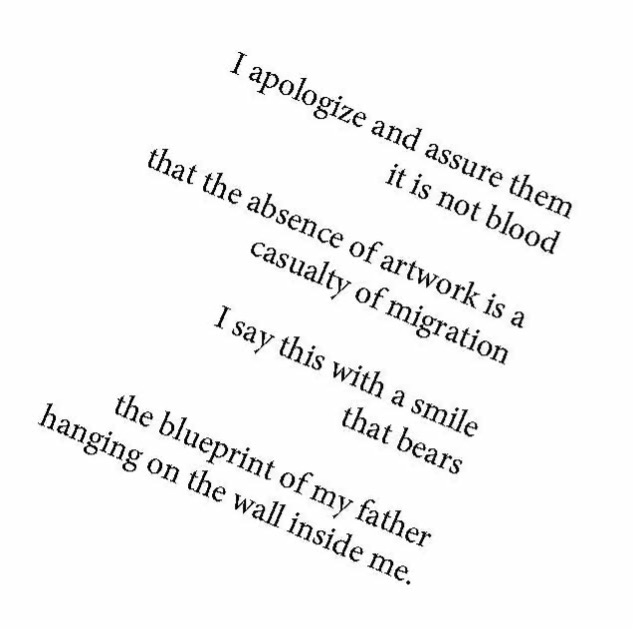

While The Book of Redacted Paintings is a meditation on loss in its many variations and manifestations — redaction and erasure, silence and empty space, evaporation and death — Kayzakian is attuned to the ways presence inheres in absence. In “Stain on the Wall,” a poem that hangs at a precarious angle on the page, prospective homebuyers pause at the wall where the painting once hung and note a stain. The absent painting’s presence remains. The poem pivots to presence in its genetic form:

The investigation into the stolen painting weaves through poems and correspondence (including a letter from the FBI’s Art Crime Team!). The painting is never recovered. What’s more, the missing painting’s absence deepens and metastasizes; its very existence grows tenuous. We come to discover that the painting that figures so prominently in the book does not exist. In “Bibliography of Paintings that Never Made it to the Wall,” Kayzakian writes, “This painting does not exist, but in some version of this story, it was stolen in winter, the season my father was late from the war.” The painting does not exist, except in stories, where it does. Elsewhere, an organization known as The Art Restoration Center writes that the painting cannot be recovered because it has been “redacted from reality,” its existence extinguished.

In counterpoint to The Book of Redacted Paintings’ narrative and poetic variations on the theme of loss is the book’s argument for the vivifying power of art in the face of dispossession and the redaction of people and places by people and nations. In “Just Because My Father was Never Painted Doesn’t Mean the Painting Doesn’t Exist,” Kayzakian puts it this way:

What I do know well: Electrons surging in his laughter.

My father is alive while I write this. My father’s painting

is not alive while I write this.

He doesn’t hold a divorce letter, but it’s there waiting in his hand.

Experts say dark energy has its place in the universe.

My father is alive while I write this. It’s an argument implicit throughout the collection but explicit here: in writing, one can bring into existence what has been taken. In stories, people and their stories and paintings exist. They live.

Kayzakian’s answer to the loss of the painting, and, by extension, the loss and absence of the dispossessed, is to find in absence an invitation to create. Where paintings and poems are missing, poems and paintings can be created. In “Questions Truths and Lies on Art Trauma,” Kayzakian renders the predicament in question form: “Does the absence of a poem on a wall make you simmer? Do you think about the burning houses in your head?” A few lines later, an invitation suggests a solution: “Has anyone ever painted you?”

For the artist, absence can be the opening of a new horizon, aperture of possibility, reclamation of space. The Book of Redacted Paintings is a work about loss that makes art out of loss, with poems that bear holes and scars of redactions as central to their poetics and vitality. But what the reader finds in The Book is, ultimately, not absence but presence: the living presence and company of these poems, their subjects, and, yes, their paintings. “I tore the first world out of this book,” Kayzakian writes in an early epigram. “Do you see birds flying out of the holes in my song?”