Two years after its world premiere, Mohammad Shawky Hassan reflects on the original story that informed the making of Bashtaalak Sa’at / Shall I Compare You to a Summer’s Day? and its evolution from a blurry memory of a day on the beach to a feature-length film.

Mohammad Shawky Hassan

It was one day before your last vanishing act. You had reappeared again and asked me to go into the water with you. I told you I was afraid of what I do not know. You gently placed your left hand on my right thigh and smiled. You always smiled whenever you didn’t know what to say. Or perhaps you did say something too insignificant for me to even remember today.

I keep returning to the same image over and over again. I can almost hear the sounds of the wind and the occasional waves, blended with the smell of the Nuweiba beach sand and the distinct scent of your wet naked skin, which I now lack the words to describe.

What happened that day?

On top of the image, there is a worn out post-it note, where I had jotted down what seems to be a hasty attempt at translating a line from Iman Mersal’s text: “If what I remember is absent from the image, why am I trying so hard to preserve it?”

Why have I forgotten so many things that must have been more memorable than what I do remember? Why do I vividly remember going to the moon and back as I jealously watched you walk so gracefully into the sea, as if it were the only place you truly belonged, while listening to Hamid El Shaeri’s خدني بين إيديك، وديني لقمرة في السحاب? And why have I forgotten almost everything else about that day from this moment onwards?

And today, two years after the completion of Shall I Compare You to a Summer’s Day?, a film whose initial intention was to reflect on our relationship, I wonder how this image that sparked the entire project carved its way out of it so smoothly that I can no longer nail down the exact moment, day or even point in the process when it did.

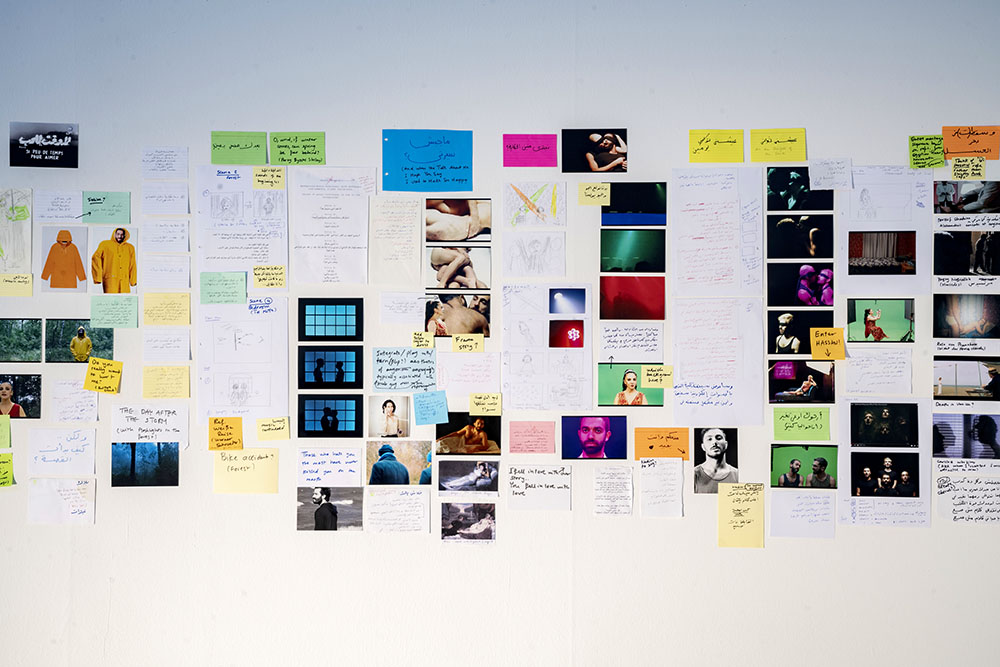

In my quest to figure out how – or if – you disappeared from the film, just as you did from reality, I went back to my earliest exchanges about the project with Ismail, who would eventually become the film dramaturg. In response to the fragmented snippets I could remember from our story that I’d shared with him over a video call, he wrote back with a few questions, the first being: “What can a chance encounter between two men by the beach and a playlist of pop songs tell us about how we imagine ourselves as loving subjects, how we imagine our idealized beloved and the ways in which the two overlap visually, musically and semantically?”

As I continued flipping through my notes, I wondered if it was even possible to discern what was “real” from what was imagined, desired; from what could be and what could have been. What happens when we live stories that don’t fit into the tropes represented in mainstream films, series and songs; and by “we,” I mean provincial kids like me, whose notions of love and relationships were shaped almost exclusively by pop culture? And how far are we willing to go in warping these stories so that they actually correspond to the labels set by these cultural artifacts?

What you and I shared escaped, and perhaps transcended, the notion of a relationship as we know it. When someone comes up to me after a screening and asks me who you are, since the film is dedicated to your memory, I find the question not only intrusive and to a large extent inappropriate, but also impossible to answer. How could I articulate what we had when I never knew what it really was and could never fit it into any of the relationship formats I was familiar with? And this is even more true today than it was when you were alive.

Perhaps it is because of this perplexity that the film, much like our story, had to be equally rooted in reality and fantasy, at once a documentary and a fairy tale, taking its substance from what happened – or what I thought had happened – and its form from a folktale collection as detached from reality as One Thousand and One Nights.

But that’s not where it all begins.

About 12 years ago, as part of a Super 8 workshop I attended in Brooklyn, I made a 6-minute essay film in an attempt to process one of your disappearances, I can’t remember now which one. I shot and edited the film in less than a week; it was one of the fastest things I ever finished in my entire life. Even the title I gave it, On a Day Like Today, is telling of how blurred my memory of you was, even back then.

The voiceover, recorded in English, was a collage of texts written by Virgina Woolf, Elias Khoury, Rabih Alameddine, Allen Ginsberg and Chris Marker. After the first –and only – public screening of the film, I wanted to create a subtitled version that I could share with an Arabic-speaking audience.

Creating a subtitled version of the film, however, meant that the original and the text would, unlike in literary translations, coexist on one plane, where the “image,” the sound recording and the written text come together to create a single image, whose elements are no longer separable. For some reason, the juxtaposition of the texts, narrated in English and written in Arabic, didn’t feel right. The other option was to record the voiceover in Arabic, thus creating two different versions of the film.

After some experiments, it seemed that no translation would be possible if it only strove for a likeness to the original. Not only that. The new version of the film, unlike the English one, implied automatically, and without intention or deep contemplation, a revelation of a queer sexuality. The beloved, whose gender was concealed in the neutral English “you” became the clearly gendered Arabic “أنتَ”. The new film would be, without a doubt, a letter written by a man to another man, or possibly a number of men.

At that point, it became clear to me that I was no longer interested in a direct translation of the original; it would simply have to be a new work altogether. And just like the lines were blurred between reality and imagination, between images and sounds, they were now blurred between original and translation. Ten years later, the attempt to translate a 6-minute gender-neutral essay film had morphed into a 66-minute collaborative queer musical, which bore little or no resemblance to the original.

In the course of developing the new film, your story, initially meant to be the central narrative around which everything else revolved, kept slowly disappearing, one part at a time. That mental image of you walking into the sea as I listened to my playlist withstood all attempts to materialize, and just like you, dissipated into thin air as you slowly transformed into a Merman.

I say “mental image” because it was not you in that picture at the beginning of this letter, but a friend of mine who looked a lot like you from the back. He helped me recreate that moment a few years back, but I accidentally opened the camera’s film door and partially ruined all the images. Just like you adamantly refused to leave any trace behind, you somehow managed to escape any possibility of recreation.

Even when I thought about writing this letter, I went to look for the messages Lina and I had exchanged about you after she first watched the film, but remembered I’d lost my chat history after reinstalling Signal on my phone, not knowing that I’d lose all my messages. When I asked Lina, she also couldn’t find them. When I remembered I had forwarded the messages to Daniel at the time, I asked him to try and find them in our chat history, which he had meticulously backed up, but somehow two months of the three years of which we’d known one another had gone missing, including January 2022 when I’d forwarded him those messages.

Looking back at it, it would have perhaps been a betrayal to you if you’d ended up in the film as yourself instead of the fantastical imaginary figure you magically mutated into.

Do you see now why I find it rather difficult to answer people when they ask me who you are? For things have transformed so much that you are no longer you, and I am no longer I, and even the storyteller that Donia and I fashioned for the sake of the film is no longer the animated Shahrazad we grew up hearing and watching.

The “real” stories, or more precisely our recollections thereof, became departure points, working materials rather than targets for accurate recreation. And as I worked with Xero, Nadim, Salim and Ahmed * on translating our personal experiences, often painful ones, to a film that we wished would transcend the limitations of our stories, I grew more and more distant from the original material.

Just like you transformed into the amphibian creature I always imagined you to be, all other personal narratives transformed to a collective imaginary loosely located between what was and what could have been, and the details have become so mixed up that even the words uttered by any of us were, as Hassan eloquently pointed out after one of the screenings, impossible to trace to their original source.

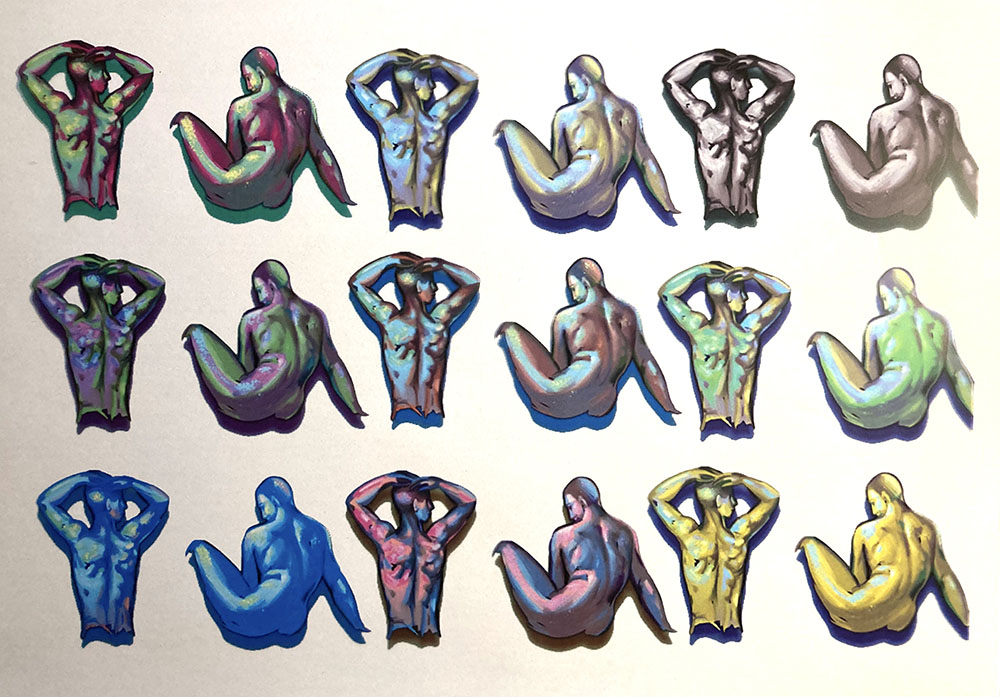

The One Thousand and One Nights motif that I had insisted on using at the beginning of the process became no more than a reference that Amen used to create over a dozen short miniatures to punctuate the chapters of the film. The beach, the forest, the bed and the club were no longer the places where relationships began or ended, having been transformed by Veronica and Carlos into generic spaces that others could project their own stories into.

To turn people, stories, spaces and memories into a film meant remaining partially focused on what “works” in terms of narrative, performance and aesthetic rather than being fully immersed in a memory of what happened. It meant endless repetitions, getting lost in tiny details such as picking breathable fabric that could absorb the dancers’ sweat throughout multiple takes, spending hours with Mariam selecting the songs that make sense for the narrative, grouping scenes into shootable blocks with Alaa sitting patiently through choir rehearsals as Khyam asks the singers to repeat the same line of a song again and again till they are fully in synch, chopping and discarding texts with Carine in the editing suite to tighten the rhythm of a sequence or hearing every word of my mourning text repeated over and over as Kinda experiments with the frequencies of my voice while I chop tomatoes in the kitchen.

The shapeshifting that has become characteristic of the film didn’t cease even after its completion. When news broke in Egypt that it would coincidentally be the only feature-length Arab film screened at the Berlinale that year, what seemed at first to be a scandal evolved into an extravagant week-long sharing of the film poster – ironically by its opponents – resulting in the image of three naked intertwined male bodies occupying the digital public sphere in Egypt. And as both Xero and Iskandar sharply observed, the “gay gasp” mimed by four of the film’s main characters, the result of a random idea offered up by one of the choir members at the end of a long recording session, ended up being the trademark image of the film, as if a clairvoyant commentary from them on what was going to happen and an extension of the film’s narrative beyond its limited duration.

And while you might have been absent from the film in the literal sense of the word, with the exception of the little hints that only you would get, the essence of what we shared remains ubiquitously present throughout it all. The bewilderment, ambiguity, elusiveness and transmutation that you embodied still loom over every single part of it. But today, as I keep trying to remember the details of that day on the beach, I still wish I had an image.