This review discusses three new books of Iranian women’s photography and art, edited respectively by Anahita Ghabaian Etehadieh, Bridget Reaume and author-illustrator Roshi Rouzbehani.

Breathing Space: Iranian Women Photographers, edited by Anahita Ghabaian Etehadieh

Thames & Hudson 2023

ISBN 9780500027158

Malu Halasa

Since the Islamic Revolution, photography by women has been a barometer of social change in Iran. Shiva Khademi’s portraits of “The Smarties”— Gen Z women who dyed their hair and refused to wear the hijab — were taken two years before the death of Jina Mahsa Amini sparked nationwide protests. The forthright expressions of the young women staring into Khademi’s camera are unnerving; they could have been Goths or hardasses anywhere in the world.

While the nationwide protests were still ongoing earlier this year, the Tehran magazine Nadastan published a special women’s issue, with articles about “the smallest woman in the world,” pioneering Persian early educationalist Bibi Khanoom Astarabadi (1859–1921), and hair in its many manifestations: as wigs (India is the largest exporter of hair) and in literature and history, from the white hair of Zal in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh to Rapunzel’s shorn locks.

The cover of Nadastan featured the rear view of a woman’s full head of curly, dark hair, an image taken by the magazine’s photography editor Mehri Rahminzadeh, who once put pregnancy tests on the magazine’s cover. Nadastan’s “hair” issue was published at a time when the Islamic Republic, bruised by international condemnation of its violence against Woman Life Freedom demonstrators, was in retreat. The magazine’s issue was not commented on or chastised in public, although an Iranian woman journalist who had left the country around that time had suggested to me that another red check had been placed by somebody’s name and trouble from the government begins when there is a proliferation of red checks.

Today, the harassment and arrest of unveiled women is once again on the rise, more recently with the death of 16-year-old schoolgirl Armita Geravand, last seen on Tehran Metro CCTV being carried out of the train by her friends after a violent encounter with the Morality Police. (Geravand died on October 28 in a military hospital). Today, Nadastan hair cover might not be so easily ignored. Photography in Iran remains a critical art form, despite government efforts to curtail it. Magnum photographer Newsha Tavakolian comes from a generation of photojournalists who had been targeted by the authorities for covering the 2009 Green Movement mass protests. She has spoken about the last image she took as a photojournalist in her country. A male demonstrator at a Green Movement rally turned around, noticed her camera pointing in his direction and covered his face with his hand; he wanted to avoid possible identification and arrest by the authorities. This was before the widespread surveillance cameras and facial recognition that the country relies on today, and photographers and ordinary people were often harassed by the security services to provide the names of individuals or the photographers taking pictures of them, who had been protesting on the streets. Understandably Tavakolian, and other news and documentary photographers and filmmakers beat a retreat from public spaces into the privacy of the artist’s studio.

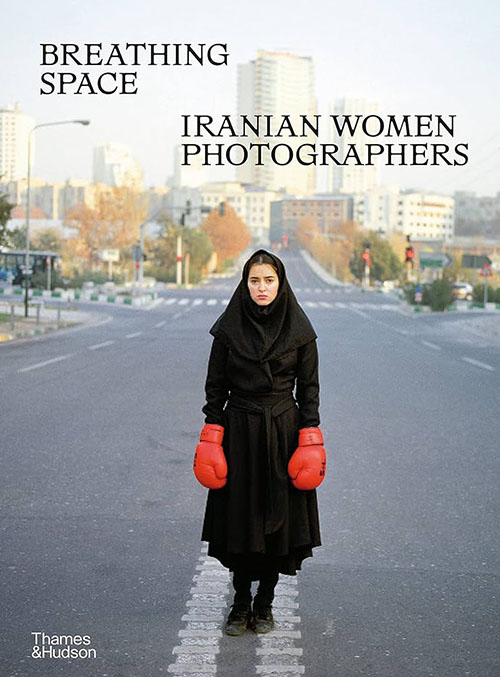

A world-weary woman in a hijab wearing red boxing gloves stares out from the cover of the large format picture book, Breathing Space: Iranian Women Photographers. The boxer, from Tavakolian’s Listen, 2010 series, was among work by 23 photographers across three generations included in this lavish collection edited by Anahita Ghabaian Etehadieh, the curator of the Silk Road, Tehran’s first photography gallery.

Listen is Tavakolian’s response to Iran’s religious bans which prevent women from singing solo in public or recording their own CDs. The female boxer on the book’s cover is just one of several faux CD covers Tavakolian created for her art series, which also includes portraits of Iranian divas such as the “Voice of Kurdistan” Sahar Lotfi who insists on singing despite the religious strictures against female voices.

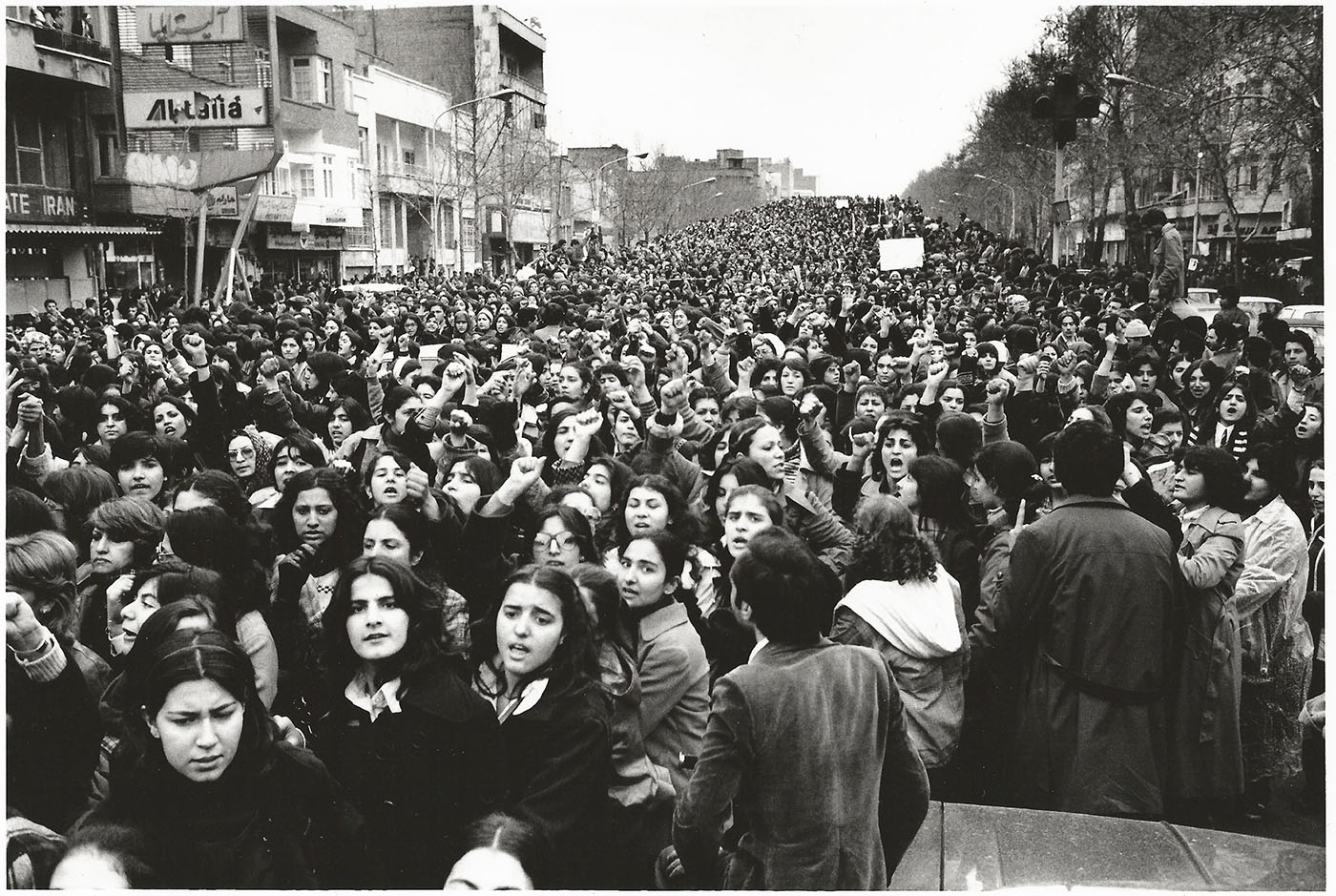

Contemporary photography came of age during the 1979 Islamic revolution. During a nationwide news blackout, pictures of the bloody battles taking place on the streets were taped to Tehran’s city walls for all to see. Opening Breathing Space are the black and white photographs from Hengameh Golestan’s “Witness” series showing the mass women’s protests against compulsory wearing of the hijab that took place weeks after Ayatollah Khomeini came to power in 1979. Forty-three years later, during the Woman, Life, Freedom demonstrations, photographs from Witness appeared on the city’s walls, in impromptu exhibitions.

Understandably, the women in Golestan’s images are angry. One in particular can be seen lecturing a mullah. The women of Golestan’s generation had fought in a difficult, often violent revolution. Their reward was the wholesale loss of their rights, from employment to divorce after the Islamic Republic came to power. Even female photographers were targeted in the state’s pushback to return women into the home.

Golestan, considered the doyenne of Iranian women’s photography, had planned to cover the Iran–Iraq (1980–88). Her husband Kaveh Golestan (1950–2003), the iconic Iranian photographer and cameraman, was already on the frontline. When she sought official permission to cover the war from Ershad, the Ministry of Islamic Guidance, her request was denied. A ministry official told her that her time would be better spent at home, making pickles and jam for men at the front.

To this day, the war casts a long shadow over the young and old women photographers, in Breathing Space. Rana Javadi also photographed the 1979 Revolution. With Golestan, she too had sought a permit from Ershad to cover the Iran–Iraq war and was refused, because of gender.

From her studio she created the series Never–Ending Chaos, from her own photos of from historic tiles from a religious site in Kermanshah (the Kurdish city which saw heavy action in the war) and images of the actual war, including those by Javadi’s husband, the well-known photographer and teacher Bahman Jalali.

Ghazaleh Rezaei in her series The Martyrs, 2021, also uses the images from a male family member — in her case her uncle — who covered the war when Rezaei was still in diapers. She obscures the faces of the martyrs or soldiers in her uncle’s pictures with flash to suggest the lingering, destructive and obscuring “holiness” of martyrdom.

Maryam Takhtkeshian in No Solider Has Returned from War, 2020, uses camera film past its expiry date and a camera popular with soldiers during World War II. Her photographs of modern day soldiers are eerie, shadowy images, which allude to the disappearance of Takhtkeshian’s uncle during the Iran–Iraq War and the return of his body to their family some eleven years later.

Three years after its invention of photography in Paris, two daguerreotype cameras arrived in the court of Mohammad Shah Qajar. The Crown Prince, Naser al-Din Shah, who had been given an early camera by Queen Victoria and Tsar Nicholas, became an avid amateur photographer and went on to document court life, including the 84 wives and 100 concubines in his harem. These images remained private, for his own personal use. In early renditions of Iranian family portraits, the women were missing. However by the turn of the 20th century, studio photography became popular, and ordinary Iranians, men, women and children, went to photographic studios, often run by Armenians, to dress up or act out in individual or group photographs.

Photo historian Parisa Damandan saved glass-negative archives from the photographic studios in Bam in the aftermath of the 2003 earthquake. Her seminal study, Studio Photography from Isfahan: Faces in Transition 1920–1950, charts the evolution in Iran from a rural country of clans to the rise of the “kingly citizen” with an emphasis on civic pursuits (i.e. teachers associations or other professional organizations, their members notably in Western dress). Damandan’s study also includes studio photographs taken of blond, blue-eyed Polish Jews sent to Iran once diplomatic relations between Russia and Germany broke down during World War II.

One of the best-known photo series in Breathing Space is a pastiche of studio photography. In Qajar, 1998, artist Shadi Ghadirian dressed her friends and family in Qajar period dress but added a twist. Each subject holds an emblem of modernity, one a newspaper, another a beatbox. In her series Like Every Day, 2000–2001, also included in Breathing Space, a figure photographed in a flowered or patterned chador from the waist up has instead of a face, a household implement: a rubber glove, iron, grater or plate etc.

Erasure is a theme in Breathing Space. In The Enigmatic Fringe of Existence, 2017–2018, by Nazli Abbaspour, constructs photomontages: family photographs overlaid with textile patterns, a butterfly or decrepit, old houses. These create a space where, as Silk Road’s Etehadieh writes, “Fiction and phantoms of the past are engaged in a dialogue with the present day, like symbols of a blurred identity, clouded by the ongoing series of events that have rocked Iran.”

Interestingly, many family albums, which include pre 1979 images of male and female members in states of dress considered “immodest” by the current government, can’t be shown or exhibited in public. Photographer Sahar Mokhtari cuts out certain figures in family snapshots in Oblivion Principle, 2016, or places family groupings in odd settings, tucked away on a windowsill or on a bookshelf for The Others, 2020.

A more violent removal occurs in Ghazaleh Hedayat’s Repetition, 2019 self-portraits. Scratched or whited out, her photos almost seem to border on self-harm. While in the images of Hidden, 2018, by Atoosa Alebouyeh, a high fashion concept is at play. Yet the photographer’s self-portraits always looking away from the camera, in a white minimalist rooms or spaces, seem intrinsically mournful.

A photographer’s use of a highly decorative, repetitive, colorful backdrop brings out the subjects’ individuality, as in Updating a Family Album by Malekah Nayiny. By placing vintage advertising faces from the 1960s and 1970s in unexpected places such as old doors and battered walls for her series Past Residue, 2009, Nayiny breathes new vitality into a lost time.

Today’s Iran is not considered a tourist destination, which makes Hoda Afshar’s photographs for Speak the Wind, 2015–2020, taken on islands of the Strait of Hormuz, on the country’s southern coast, so intriguing. These mysterious and strange images have been influenced by both the landscape’s natural formations and the legends brought by the slaves trafficked from southeastern Africa.

The sepia-colored A Travelogue to the Iranian Plateau by Pargol E. Naloo shows yet another devastated landscape, as Iran’s rivers, lakes, and underground aquifers fall victim to climate change and dry up. Naloo’s images in many ways capture a poetic environmental decline that are reminiscent of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s stark industrial landscapes.

One gets similar feelings of cruel, indifferent environments but this time it’s entirely manmade, on the stark highways beneath Hoda Amin’s window for her photographs, No Man’s Land, 2013–2016. In them, lone figures — their backs to the camera — walk off into a dystopian future.

Gritty realism is the real strength of the women’s photography in Breathing Space, and it is realism that worries the regime the most.

In 2012, Tahmineh Monzavi spent a month in solitary confinement in Evin Prison for her photographs of recovering female addicts in South Tehran, and Breathing Space includes her photographs of the trans woman addict, Tina. This is not how Iranian women should be portrayed, Monzavi’s jailers had told her, despite the country’s clerical support for transexuality, as opposed to homosexuality, still considered a capital offense in Iran.

So what is the acceptable image of Iranian women? According to art photographer Amak Mahmoodian (not included in Breathing Space), it is “… plain faces under hairless scarves …”

Mahmoodian is known for producing her own photobooks. Shenasnameh (birth certificate, in Persian) studied and reacted to women’s head shots required for government-issued identity documents over a period of years. Another of her books, Zanjir, includes an imaginary conversation between the photographer and Qajar princess and diarist Taj Saltaneh (1883–1936) who appeared dressed as a man in photographic archives of Golestan Palace (where Naser al-Din Shah photographed his wives and concubines).

Powerful imagery and subject matter by Iranian women photographers resist religious laws and narrow conventions regarding gender and sexuality in their country.

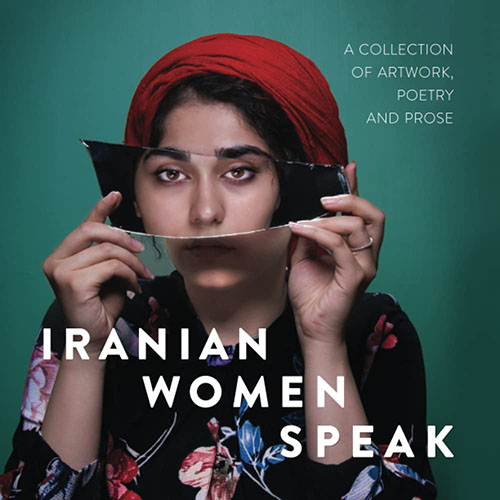

Like the anthology I edited, Woman Life Freedom: Voices and Art from the Women’s Protests in Iran, another anthology Iranian Women Speak: Voices of Transformation, in English and Persian, edited by Bridget Reaume for the International Human Rights Arts Festival (IHRAF), was published in response to the demonstrations after the death of Jina Mahsa Amini.

Iranian Women Speak includes prison memoirs and critical short essays by anonymous voices, alongside poetry by Iranian-Ghanaian poet Caroline Reddy.

One artist featured in both the IHRAF and Woman Life Freedom anthologies is Mansooreh Baghgaraei. Iranian Women Speak included Baghgaraei’s flowers embroidered with women’s hair, a piece entitled “The Liberated Hairs.”

In her artist’s statement in Iranian Women Speak Baghgaraei writes, “I asked women to donate cuttings of their hair. Each one’s hair creates a work of powerful feminine art. A woman’s hair is transformed into a medium to speak about all women, freedom and equality.”

For Woman Life Freedom, the artist gave us an embroidery showing the naked back of a woman protestor. It is punctured by red holes, to represent the wounds from a pellet gun the regime used against the demonstrators.

At the City Lights event for Woman Life Freedom, the translator and novelist Salar Abdoh spoke about differences between the opinions of Iranian women inside the country versus those in the diaspora, and how it would be a misreading of the Woman Life Freedom movement to assume that all women feel the same way.

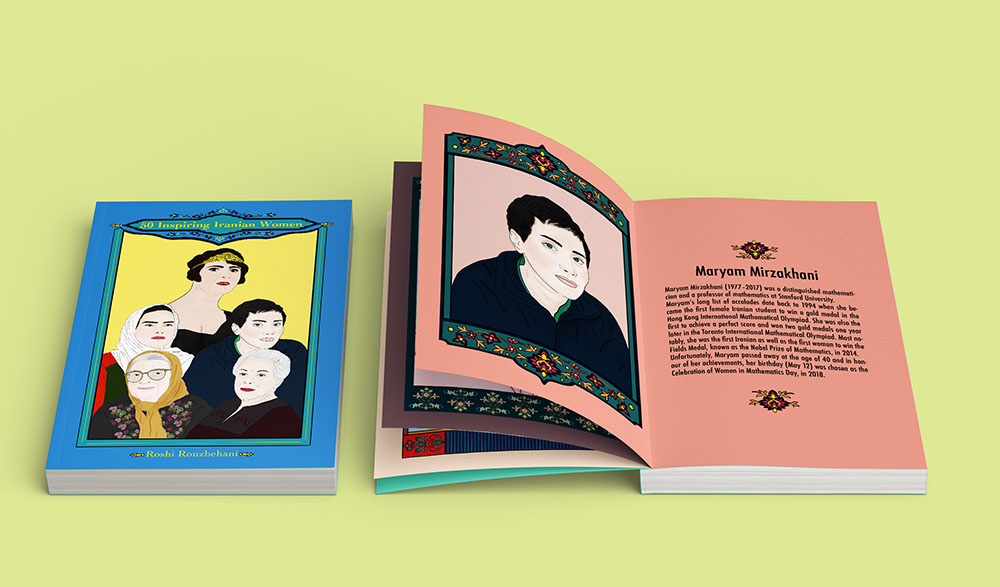

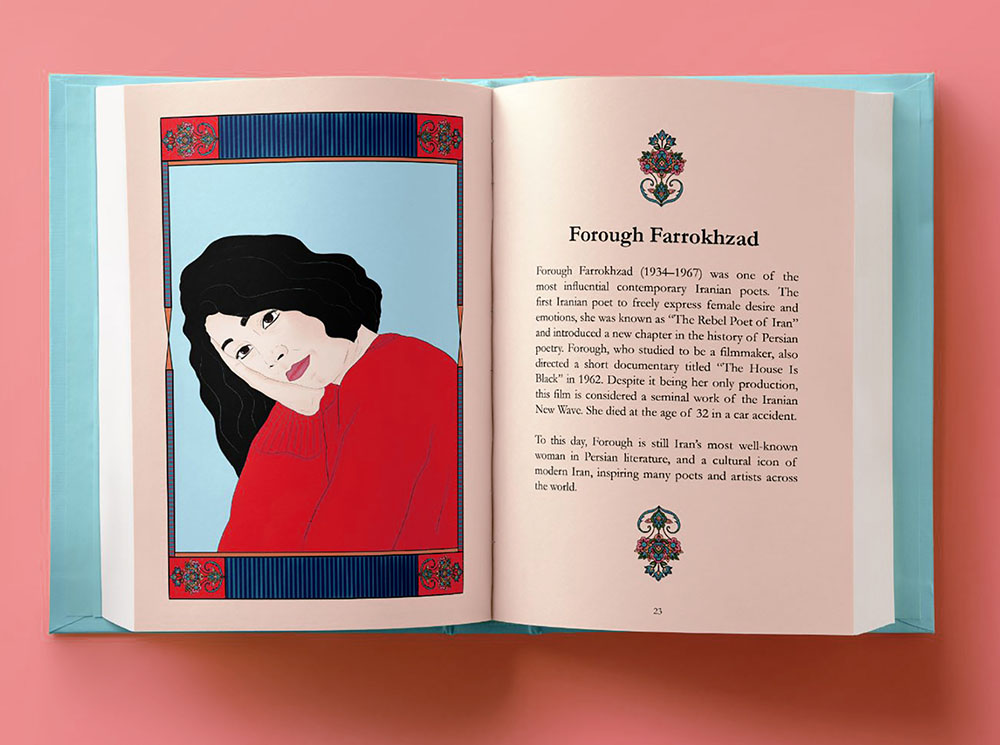

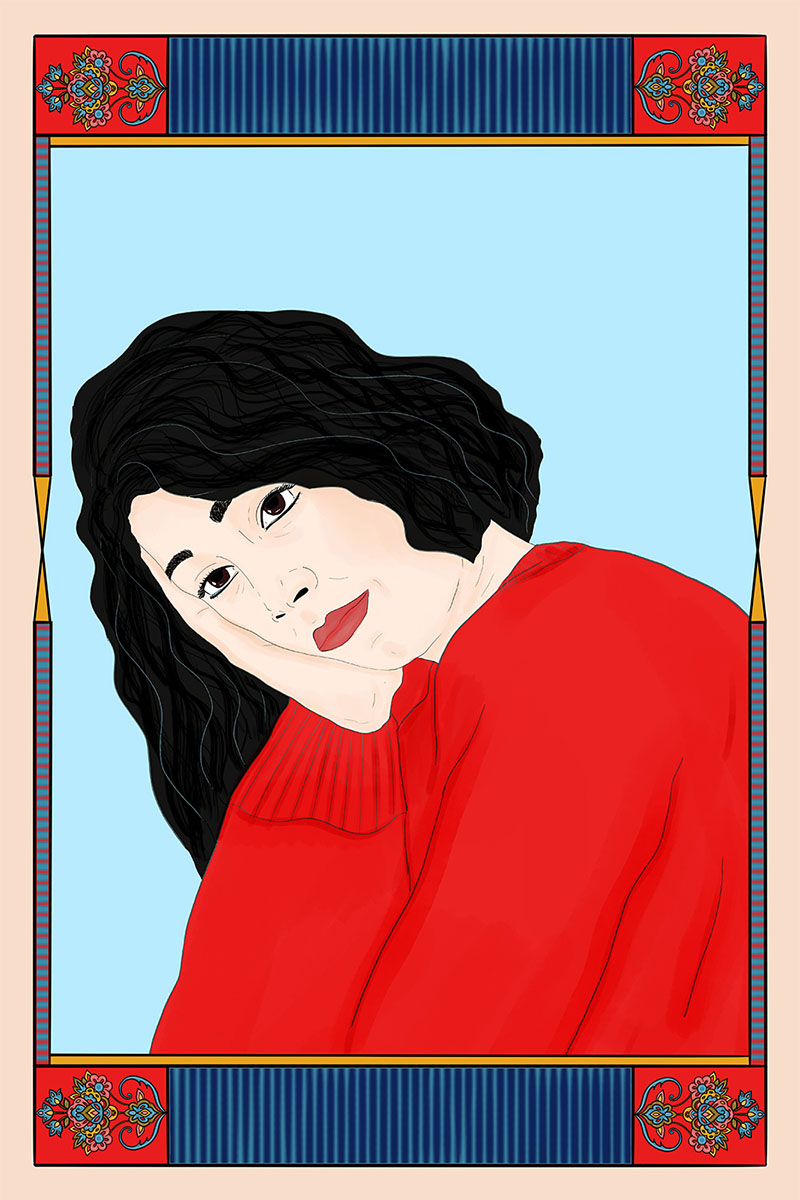

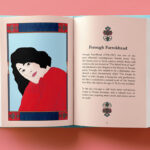

One book that celebrates female achievement at home and in diaspora is 50 Inspiring Iranian Women, written and illustrated by Roshi Rouzbehani, who has worked for The New Yorker and The Guardian.

As Rouzbehani writes in her foreword: “While there has been recent interest in celebrating the remarkable life and work of women from around the world, I do not believe Iranian women have received the recognition they deserve.”

50 Iranian Women showcases the lives women across the professions, from activism and science to the arts and sports. Many of the women’s achievements are far-reaching beyond the borders of their country. They are not household names in the wider world but they should be.