Looking for love and her father’s past, a Turkish American journalist haunts the streets of Istanbul before and after Covid.

Alicia Kısmet Eler

The sticky summer air sank into my skin as seagulls dove into the wavy blue waters of the Bosphorus Strait, the waterway that separates the European and Anatolian sides of Istanbul. My cousin and I sat on the hard wooden benches of the vapur (ferry boat) as it drifted along. I hadn’t been here in over ten years, nor had I ever been to Turkey without my dad, my baba. I’d asked him to come, but he declined. He insisted that he wouldn’t be able to keep up with me and my cousin, who also grew up abroad, as we roamed the streets of Istanbul. But I knew that was just another excuse for avoiding Turkey.

On that windy summer day in Istanbul on the vapur, I spotted an old man reading a pro-government newspaper, a middle-aged teyze (an auntie) wearing a pink headscarf covered in yellow flowers, and a young blonde woman glued to her smartphone. As a queer person who grew up in America, I was used to being able to easily find my people. But since I’d arrived in Istanbul, I hadn’t seen a gay club, let alone a rainbow flag on someone’s coat. Maybe queer people were hiding in plain sight, or maybe I just didn’t know where to go.

Maybe if I fell in queer love with someone here, I could experience the cultural reconnection that I was hoping for — that Baba had, in subtle ways, let me know he’d never give me. I grew up knowing some Turkish, but took it upon myself to finally learn it for real as an adult. I found a teacher in Minneapolis, and he became my friend and the first Turkish man whom I didn’t feel afraid of.

Over time, I gained access to Turkish language and culture, something I didn’t feel I had as a kid. Even though these days my baba and I speak Tinglish — a mixture of Turkish and English — and he’d slowly started opening up more in his native language the more my Turkish improved, his Istanbul still felt like something buried deep in memory. If I cared to discover more about the country he left behind, that was on me.

Several nights later, I laid on a king-sized mattress in a heavily air-conditioned hotel room off a busy highway on the Anatolian side of Istanbul, frantically downloading dating apps. I’d been banned from Tinder for some reason, so I downloaded Bumble, but there weren’t too many people on there. I chose men and women, and mostly swiped right. I was out of options after ten swipes. I asked a Turkish friend, Fülya, which dating apps queer women used, and she told me to try Wapa, but I didn’t feel motivated enough to download another app. One was overwhelming enough.

The next morning I matched on Bumble with Rüya, who had three cute photos on her profile. In one, she wore a black turtleneck and was framed against a yellow-orange wall, rendering her awash in a soft glowing light. There was one of a very fluffy gray-and-white cat. In another, she wore a white T-shirt with rainbows on it, her arms around a boy with light brown hair and a scraggly beard. I had to meet her, this sweet butch girl who was visibly gay in a country where I couldn’t find my people. In my mind, I told myself we’d be friends.

Over the next week, I hung out with my gay boy cousin and my 92-year-old babaanne (grandma), eating cookies and drinking copious amounts of çay (tea). Babaanne recounted memories of her engagement to my grandfather, Kenan Bey. I wondered about how her stories flowed so easily, whereas Baba’s seemed out of reach — but then again, she never had to deal with the trauma of immigration. She had always lived in Turkey.

At night, I went out to dinner at seaside restaurants with my aunt, uncle, and cousin. I scanned the crowds for visible queers but still I saw no one, not even a tiny rainbow pin. Even though my cousin was also queer he, like me, wasn’t from here. I began to fantasize about meeting Rüya.

Rüya and I continued messaging on Bumble, but it seemed like kısmet (which happens to be the middle name that Baba gave me) was against us. When she was free for lunch, I was scheduled to meet with another aunt, my baba’s sister, who later canceled on me because of unresolved feelings towards my baba’s departure from Turkey, even though that happened over 40 years ago. I texted Rüya to see if she was up for meeting, but suddenly she had to work. The next day I asked her to coffee, but she had some legal dealings with her landlord. I was sitting on a Turkish Airlines flight about to take off for Chicago, where I would catch my connection to Minneapolis, when she wrote to me. She’d just gotten off work and could meet up.

“Sorry,” I wrote her, “but now it’s too late.”

Yet when I landed in Chicago ten hours later, exhausted and waiting in the mile-long U.S. Customs & Border Protection line, I texted her. It seemed innocent enough.

Within a few days, Rüya and I were texting non-stop, a constant stream of emotional vulnerability in my pocket. I desperately wished that we had met when I was in Istanbul, but realized that maybe this ardor was possible now because we’d never met. We shared childhood photos and coming out stories, empathizing about work, friends, frustrations, and dreams.

Weeks later, when I asked her to Zoom — our first “date” — I felt giddy with desire.

I’d had phone sex before, but never with someone I hadn’t met in person. Didn’t that intimacy need to be built physically before going virtual? Here I felt the opposite. As our emotional connection grew, I quickly discovered that I didn’t care where we existed. I accepted the non-space of the Internet as ours. We went on dates, watched films and TV shows together, texted, sexted, and fell in love online.

The only thing missing was Rüya.

Two months into our virtual relationship, I left the newspaper office in Minneapolis where I worked late one evening and meandered downtown towards a wide street reserved for buses and bikes. As I crossed, my ex-partner Alma got off a bus. They looked even hotter than a few months earlier; we had broken up right before I’d left for Turkey. They’d grown out their curly black hair, and their skin was slightly tan. I remembered how much I had missed them.

Two nights later we were back at my place making love, our sweaty bodies intertwined between the sheets.

“I met someone in Istanbul,” I admitted to Alma. “Except we never met.”

I felt an immense guilt about somehow “cheating” on Rüya, but I needed my real life back. The next morning, I ended it with her. She lurked on my social media and I on hers, but I did my best not to reach out.

A year and a half later, Alma and I broke up again — this time for good. Not long thereafter, I received a WhatsApp message from Dilek, an LGBTQ activist in Turkey who was hoping to get coverage for an incident involving police attacking trans women. When Dilek said they’d gotten my number through Rüya, I felt like my boundaries had been violated. I’d told Rüya not to contact me, and I figured that this extended to giving out my number. Although I really wanted to help on a professional level, I had already given her my contacts. As such, I had nothing more to offer. I had also blocked Rüya, making things more complicated.

My anger unwittingly led me to take the first step towards reconnection: I unblocked her on Twitter to tell her that she should have asked me before giving out my number. She said she would have but that it was an emergency, and then she apologized anyway. I could have left it at that but instead, suddenly charmed by her apology, I struck up a conversation. We moved from Twitter to Instagram to WhatsApp and Zoom, as if no time had passed.

After several months and two attempts at dating people locally, I booked a flight to Istanbul. I had to meet Rüya after all this time, but suddenly things felt too serious again. Her anticipation seemed almost over the top, so I panicked and canceled the flight, and then returned to Dating IRL again; I met and fell hard for someone who was also of Middle Eastern descent. Yet, even though we lived in the same city, dating her felt impossible.

Rüya and I didn’t talk again for awhile, but when we reconnected, I told her I was coming for Christmas and New Year’s. My aunt and uncle happened to be with their grandkids in London, so I would have Istanbul all to myself for the first time ever. I made plans to stay in the city with two artist friends, Sevil and Sena. Then I booked the flight and scheduled a Covid test.

“I’ll believe you when I see you here, in Istanbul,” Rüya said. She was understandably salty, but then again, we’d still never even met.

The day before my flight, Sena and Sevil told me they’d been in contact with someone at an art opening who tested positive for Covid, and suggested I book my own Airbnb for now. The day I arrived in Istanbul, Rüya did not text me “Hoş geldin!”— the customary welcome message. “Finally,” she wrote. I did not feel welcomed.

Yet for two weeks in Istanbul, my friends stayed home feeling ill, and Rüya and I spent every available moment together. At night, we chowed down on cheese-filled vegetarian pide, sipped çay and ate soğuk (cold) baklava at outdoor cafés, cooed over fluffy friendly street cats, and crossed the Bosphorus together. When she was at work at a restaurant in Kadıköy, I’d come to visit, quickly becoming a fixture of the hip artsy queer scene there. I would hang on her arm during her cigarette breaks, kissing her sweetly between puffs. Because of the Covid scare, I saw my other friends only twice.

I felt strangely in place yet out of place, a ghost in this country that most of my family had either left or were buried in. Yet I was finally speaking and understanding the language that warmed my heart.

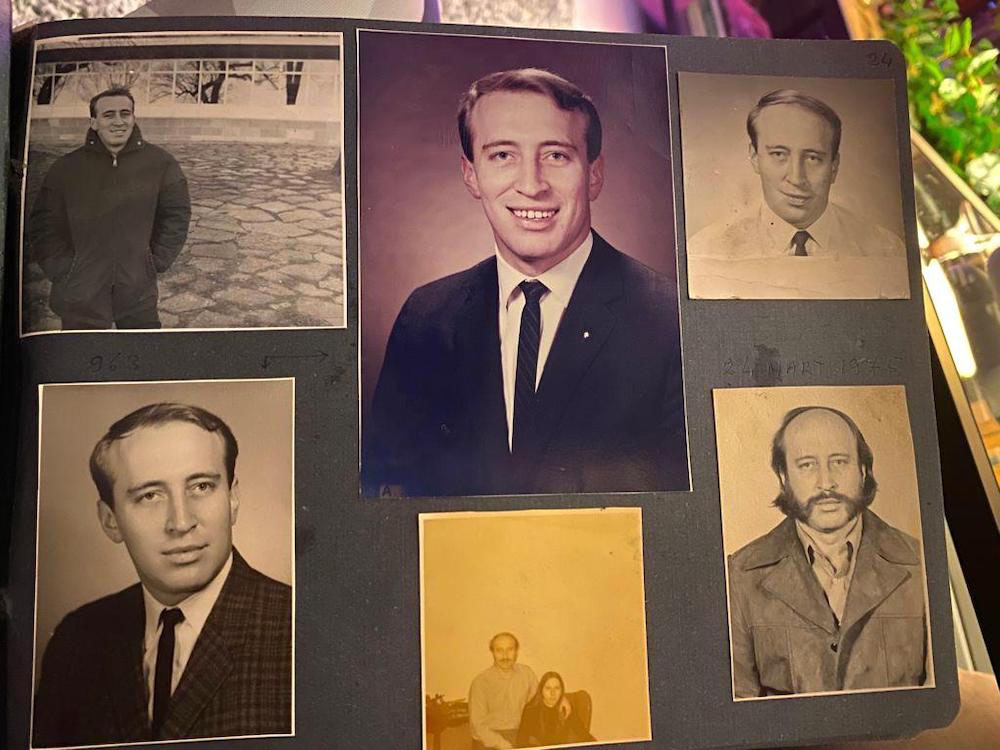

My baba had left Istanbul in the early 1960s, when the United States was offering student visas for chemical engineering. His father insisted he go and his older brother Semih stay in Turkey and join him in running the family business, a baking flour factory called Karaköy Un Fabrikası (Karaköy Flour Factory). After ten years, Baba had gotten acclimated to the American way of life. If he set foot in Turkey, there would be certain family obligations — plus he would have had to do his askerlik, his mandatory military service. So he didn’t go back, and by the ’80s, the Turkish government revoked his citizenship. In its place, he became an American. Over time, family ties loosened, and the distance between America and Turkey grew farther apart.

Growing up in suburban Chicago to a Turkish dad and a Jewish American mom, I always felt the tension between his desire to be in America and his longing for what he left behind in Turkey. It was most palpable when I’d catch him watching Turkish films in his basement mancave late into the night, talking with his younger brother on the phone in Turkish, or emailing old classmates from lise (high school) in Istanbul. Many of them had returned to Turkey, but he stayed in America.

Despite visits to Turkey as a child, I felt unresolved about my own relationship with the country and the language. There was something more I needed to discover for myself — something lost after all the time that my baba spent away from Turkey. To him, Turkey seemed like a memory, but to me it was a mystery that I longed to unravel.

One evening while hanging out with Rüya, I happened to meet Cansu Yıldıran, a queer non-binary Istanbul-based photographer whose work I had admired from afar. Later, Rüya and I went out to karaoke with some random friends of hers, and I filmed them dancing and singing to Turkish songs that I also knew, but not as well as they did. My body learned their moves. I felt like I could see myself living here, even. I felt at home.

The only thing missing, again, was my baba.

On New Year’s Eve, Rüya and I didn’t gaze up into the black sky as shots of light exploded; instead, we watched Casablanca, one of her favorite films, and FaceTimed with my best friend from Minneapolis, Shirin, who was in Paris visiting her sister who had immigrated to France from Iran. As we peered at each other through screens, I started to get the sense that something wasn’t right about my journey to Istanbul. After we hung up, I decided to ignore that thought; then Rüya and I went back to watching the film.

“We’ll always have Istanbul,” she told me, mockingly, updating Rick’s famous line, “We’ll always have Paris.”

My eyes filled with tears. I felt like I was falling in love with her for the second time, but what if this was the third act, rather than the beginning?

I cried about being able to take her to the places in Istanbul that were meaningful to my family rather than talk about them as some faraway mythical place to someone back in America whose knowledge of Turkey consisted of falafel and a college study abroad trip.

We went to my grandfather’s old office building in Karaköy near the Golden Horn, the street where my family’s summer home used to be in Kadıköy, and grandfather Kenan Bey’s old apartment building in Nişantaşı. I even went to Kenan Bey’s grave. We walked through Göztepe Park near my now-deceased babaanne’s apartment — the visit in 2019 with my cousin was the last time I’d see her. Although Baba had visited Istanbul ten years earlier, he never got to hold Babaanne’s hand again. I knew they’d had a complicated relationship — she was his stepmom after his father divorced his mother and then remarried. Divorce in 1940s Turkey was uncommon. I wondered what other family secrets he was hiding from me. Still, I wished that he’d come with me, and that we’d visited all these places together, too.

“You have more of a connection to Istanbul than I do, and I’ve lived here for almost fifteen years,” Rüya said to me one day.

But did I? If I did, why was my connection to Istanbul surfacing as something I began to think of as “memory tourism”? I texted Baba photos of all these familiar familial places I had visited, and his responses were sweet but felt faraway. “Çok iyi ettin, kızım,” I’m happy that you did that, daughter” he’d say. He seemed distracted and distant, but that distance was the same feeling I remembered from when we were in Turkey together as a kid. Although I caught glimpses of how happy he seemed to be when we were here, they were often quickly drowned in alcohol.

I started to wonder if I was actually just a tourist of his memories: a person, lurking in someone else’s past, who wanted to be forgotten. What was I doing here? Then my flight or fight response kicked in.

I needed to get out.

As my departure date quickly approached, I cried every night thinking about being away from Rüya, and how impossible our relationship felt, especially as the Turkish lira plummeted. Then, because of an error in the Turkish Airlines system, I missed my return flight.

We were gifted a few more days. I stayed at her apartment instead of random Airbnbs, and suddenly we’d entered the “living together” phase, a fast-forward into a future of something that could never be. Before I left, she insisted I take a house key with me. She said that she gave a key to a lot of her friends, and, if nothing else, wouldn’t we remain friends? I felt nauseous about the uncertainty of it all, yet she wore a relaxed façade.

On the flight to Chicago, and then on my connection to Minneapolis the next morning, I held out hope that we would figure this out and be together.

Back in Minneapolis, I observed my immigrant friends from Iran, Italy, Colombia, and other far-flung locations long for their home countries. I wondered why I would want to return to a distant place that I imagined as home, but where I was a ghost, a tourist of my baba’s memories.

Within two weeks, I ended things with Rüya. After having finally met, the fantasy of what she represented for me was over and our very painful long-distance reality had set in. The prospect of not being able to see each other again for at least six months, and the fact that I’d known her in-person for only two weeks, didn’t feel like a healthy foundation for a long-term relationship.

The Turkish part of me wondered if I was denying the existence of kısmet, of my fate with Rüya, whose name means “dream.” What if I was being overly American about it, trying to determine my own destiny? The Turkish and the American parts collided. Was this how Baba felt when he didn’t do his askerlik, and chose to stay in America despite missing his family, language, and culture?

And what about Rüya? I had to believe that in some ways, things with Rüya were over before they began, and the best parts of our affair happened at the beginning, virtually, and at the end, in person. But for me and Baba, it felt like I’d started to crack open the door to his Turkish past. He may have decided not to return, but what if I did, in some form? What if the ghosts weren’t there to haunt, but to gently nudge? What if I ended my tour of his memories and started my own?

Rüya and I talked sporadically, but over the next year it became clear that our romance was over. My solo trip to Istanbul did bring me closer to Baba. My Turkish improved, and I felt like I made more connections with people my age in Turkey.

This year, Baba turned 82. He survived a cancer scare and subsequent surgery. He made peace with his older sister Esin who wouldn’t meet with me when I was in Istanbul. This summer, he wants to go to Turkey, and now he’s the one who keeps bringing it up. We speak Turkish together all of the time. He recently told me I’m the only person he regularly speaks Turkish with, and how it’s good to keep speaking it so that we won’t forget. It’s a radical change from his previous desire to forget.

Even though he didn’t teach me Turkish as a child, I forgive him — I had to find it on my own, and since I did, it’s become another layer of our special father-daughter connection.

My continued interest in Turkey has brought him around to telling me more stories about his childhood, his memories of his grandfather’s flour factory Karaköy Un Fabrikası, and his early days as an immigrant to America. Maybe we will go to Turkey this summer after all, inşallah. In the meantime, back in Minneapolis, I’ve made friends with more Turkish people and immigrants from other countries, and found myself in a space of acceptance and healing about my baba. He did what he had to do by staying in America, and I did the same but in the opposite way — by going back to reconnect with my Turkish roots.

Maybe memories don’t have to be painful. Maybe they live among us, even when we aren’t consciously thinking about them. Maybe they are our beautiful ghosts.