In this introspective contemplation, an Iranian woman reflects upon her progressive perspectives regarding her own sexuality, which are juxtaposed against recollections of a more traditional upbringing in Iran and a yearning for the liberating artistry of Forugh Farrokhzad.

Fargol Malekpoosh

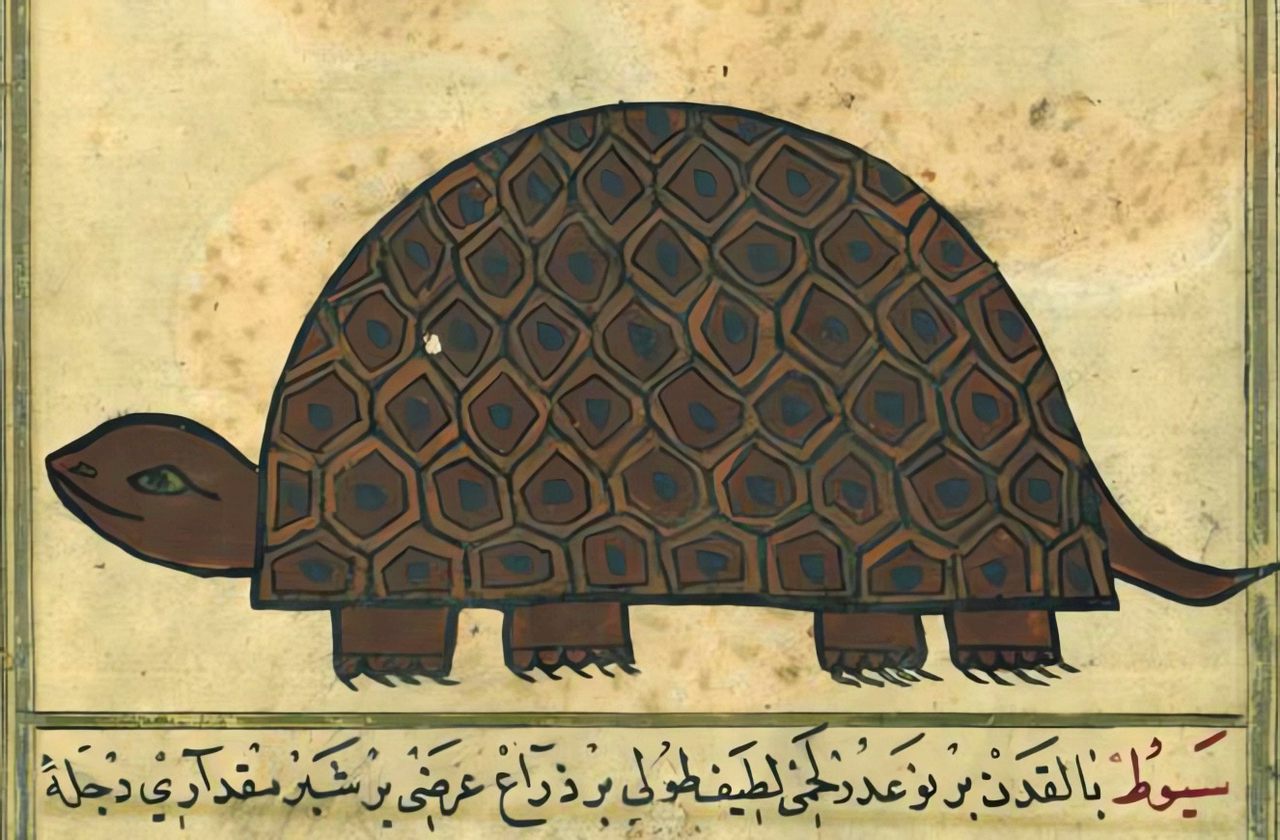

Baba hates that I have sex. And when I say hate, I don’t just mean the usual bile-spitting hate that starts yapping the moment it gets a whiff of that unlucky thing which is the object of its loathing. No, no. That kind of hate at least implies the existence, the being-a-thing-ness, of the hated thing. It gives hate a target to shoot at. Baba’s hate is a hate of the non-antagonistic sort. A tortoise-shelled hate. A Baba-shaped tortoise. I snort a little at the thought.

“Hm?” asks N, half-interested, half-sun-dazed, lowering his book to look at me.

“Nothing, nothing. Just silly thoughts.” I smile at him, reaching over to tickle his forearm. “Tortoises look kind of fucked-up, don’t you think?”

“Like constipated old men. Like rock-hard turds,” he replies. We laugh.

A tortoise-shaped Baba. His hate, like a shell.

In the late springtime, a green bird with red streaks on her breast, searches for her mate in the garden. She hops from tree to tree, shaking small berries off the branches as she lands. Today’s dance reduces the fallen red currants to a berry-pattern smear that she leaves behind for her lover to find. But the brown-shelled tortoise (eyes no longer brown but milky with cataracts) does not like the sound of her shrill song. He winces at her scarlet-breasted fluidity, the flashes of green and red frightening him. He cannot bear her passion. From the sunbed, I watch the tortoise slowly retract his head. He is a heaving, frowning mass, slow and awkward. Perhaps the bird’s dance makes him nervous, a little embarrassed even. Maybe he’s just constipated. Either way. With one final strain of his neck, he tucks himself away into a shelled oblivion. Object permanence is not a talent tortoises have, I imagine. Probably not a talent Babas have either.

In the safety of my shell, there is no bird, and there is no birdsong, I imagine the tortoise sigh.

I wonder what Baba would think of me now, reading Forugh Farrokhzad as my thighs soak up the warmth of the sunbed and the sun creeps up on my chest, painting it red. I look across at N, his cheeks are pink and warm. He is beautiful, I think to myself, his arms like veined marble come to life.

The cat comes up to me; she weaves in and out under the chair. She is old, and she is waiting for me to love her. She squirms around on the grass. Back and forth she rolls, baring her white tummy. I put my book down. It’s a copy of Sholeh Wolpé’s translations of Forugh Farrokhzad. The cat purrs in my palm as I scratch her little goateed chin.

“Good girl! You want cuddles, don’t you? Such a good baby!”

I coo to cats as if they were newborns, my head tilted to one side, a warm smile on my lips.

The last stanza of the poem still rings clear in my head. Together we chant:

Under the shield of night,

let me unburden the moon.

Let raindrops fill me with tiny hearts,

with unborn children.

Let me be filled.

Perhaps my love may be

the birth cradle of another Christ.

Baba is a reader — or at least he was. Now his eyes are dry and his English embarrasses him.

I think back to a dry summer’s day ten years ago. Maman is taking me down to the old family garage in Tehran. An off-white corrugated door, its metal speckled with black soot, opens to reveal piles of books that Baba has kept from before the Revolution. My Baba, the bandit, the vigilante poet! Baba, the champion of writers and of writing! I glow with pride for his love of freedom, for the way he cherishes literature and the Arts. I imagine him pulling out books from the flames of a bonfire. I am proud to be his daughter again.

Under the shield of night,

let me unburden the moon.

I wonder if Baba, seated on an old stool in Maman-Bozorg’s courtyard, his hands cradling his ears against the shouts of children playing ball games outside, had ever come across this poem. I imagine his eyes trailing the lines from right to left, sounding out each word and letter under his breath as he savors the silences in between. Today, I sit in an English garden, reading the same poem, although not the same words. I must try to read these in Farsi one day, I tell myself. Had he loved this poem or hated it? Did he have to crane his neck at an angle from his shell to better observe the words, as they unfolded in mists of blue, green and red? I would ask him — but I am afraid. I wonder whether our Forughs are even the same.

Today, my Forugh paints this little English town in new shades of blue, green and red. I look at N and I smile. Oh, how he kisses me till I am robin-breasted! Oh, how he embraces me so that each sprouting hair on my body is at once a leaf, my body a green meadow of grass scattered with red berries. For a moment, I play poet. My voice rings out through the garden. I wonder if Baba can hear my song over the walls of Maman-Bozorg’s courtyard.

I turn the book over in my hands. Wolpé had dedicated her book to the women of Iran: “For all the women of Iran /as Forugh says/ May you be green, head to toe.” I shut my eyes and pray too, three voices as one.

Later that day, N and I walk through the town streets and stop at Whites of Kent, a lingerie shop.

“I wonder if they’ll let me in,” I joke. It’s a stupid quip, coarse and half-funny — but I knew it would make him laugh.

“Ey baba,” he chuckles. I think it’s sweet that he’s picked up some of my phrases, how he draws out the vowels — his attempt to sound like me. I intertwine his hand in mine.

As we walk toward the town square, I watch some birds groom themselves clean in a flower bed. In the park opposite, a couple of kids are tossing a ball.

We claim a bench, and sit cross-legged, facing each other to share a cookie.

“I hate goodbyes,” he says.

“Me too,” I sniffle. “God, we’re dramatic… I’ll see you in a month at most!”

He touches my cheek and I press my lips gently to his forehead. An old man in brown trousers and a brown shirt walks by.

“Get a room!” he shouts.

I want to believe he’s being funny, but I’m not sure. We laugh anyway.

*All references to the translated poems of Forugh Farrokhzad are from Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrokhzad, edited and translated by Sholeh Wolpé, (Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2007). The quoted lines are from Wolpé’s translation of Farrokhzad’s poem “Border Walls.” They make up the final stanza of the poem.

** Glossary (Persian to English)

| Baba | Dad |

| Bazaar | Market |

| Ey baba! | Golly! (literally Oh, dad!) |

| Maman | Mom |

| Maman-Bozorg | Grandma |