For Americans and for Arabs and Muslims around the world, September 11th will live on as a cataclysmic day that changed our lives inexorably. But many years before the attacks in 2001, Chileans lived September 11th as the coup that stole their socialist democracy — the day that Salvador Allende was violently usurped by General Augusto Pinochet and his stealthy American backers…

The Suicide Museum, a novel by Ariel Dorfman

Other Press Sept. 5, 2023

ISBN 9781635423891

Francisco Letelier

There are stories that fill an indispensable place in the realm of the imagination. And then there are stories that are seldom heard, but that are equally essential, waiting for someone to give them voice. Transplanted to unknown places and forged with new languages, the best tales do not need conclusions. We are all marked by departures and arrivals that we carry like invisible tattoos. Translating ourselves into new vowels and sounds, onto rivers and mountains, hospitals and cemeteries, it sometimes feels as if as if they have waited for our arrival.

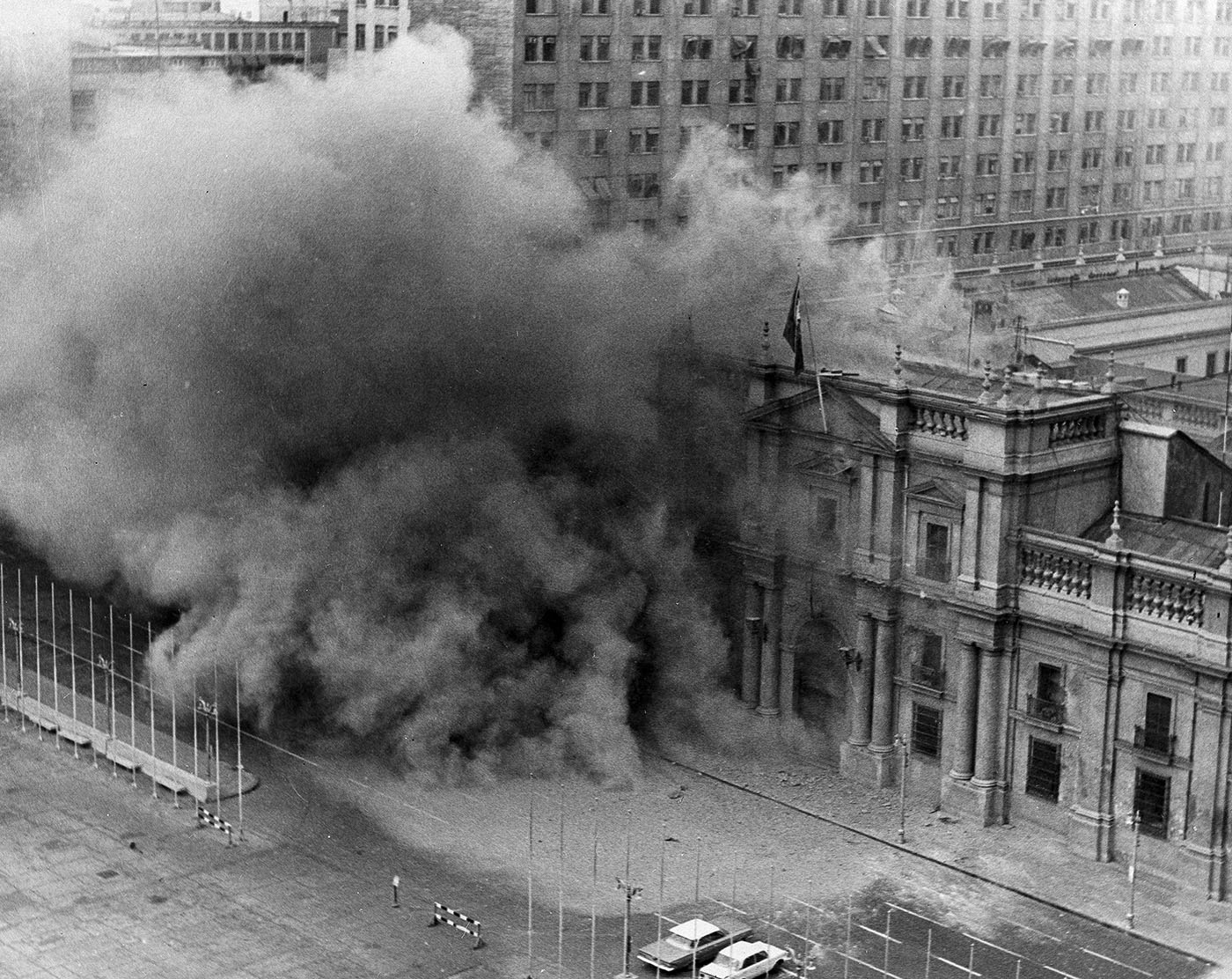

In his latest novel, The Suicide Museum, Ariel Dorfman opens a wide tunnel into history and tackles well-known events in a surprising, genre-twisting manner. The novel is essentially a memoir disguised as an investigation into the death of Salvador Allende — the immensely popular Chilean socialist president who died on September 11, 1973, when the Chilean armed forces, with the help of the United States, staged a violent coup and bombed the La Moneda Presidential Palace. That was a day that changed the lives of Chileans forever.

Dorfman’s new novel returns to events and concerns covered in many of his earlier works, but The Suicide Museum skitters between history and fiction, and even those well-acquainted with the events and characters that appear in the novel may find themselves adrift, wondering where one ends and the other begins.

The author has been accused of being one of Latin America’s greatest novelists, but don’t let the label lead you to assumptions. As a playwright, essayist, academic, and human rights activist, Dorfman is decidedly versatile, and those hoping to find a heart-warming story of challenges overcome are in for a surprise.

Dorfman explores the many facets of exile, belonging and displacement, revealing intimate personal experiences conjoined with political history in a manner that bravely leaves open questions, adrift like flotsam in still-turbulent waters.

I certainly drifted in time and place, but let’s begin with understanding that I cannot give an objective review of Dorfman’s latest, for I am entirely biased. The writer and his wife Angelica (who plays a large role in the novel) are close friends of my family; they have known me since I was a young teenager. My family shared grief and exile with Dorfman and his family in Washington DC, after my father Orlando was murdered by a hit squad under orders from Chile’s dictator, General Augusto Pinochet. Ariel and Angelica’s oldest son, the noted filmmaker Rodrigo Dorfman, is also a close friend.

Consider these lines as my personal notes disguised as a review of The Suicide Museum. In the novel and in real life, Dorfman is in Santiago, Chile on September 11, 1973 — but not at La Moneda, as some have said. In the moments described by the author in the novel, but also in real life, my father is also thought to be at the presidential palace. A few blocks away from La Moneda, I am with my mother Isabel and three brothers at Avenida Ismael Valdés Vergara, on the sixth floor, where huge araucaria trees mingle with Chilean palms and oriental plane trees in the Parque Forestal outside our window. Trucks full of soldiers and small tanks trample the manicured paths below, as loud explosions shake the streets. Hours later the phone rings. We are resigned to bad news and learn that my father has been taken prisoner, but is alive.

Just a few blocks east, Dorfman will seek asylum in the Argentine embassy, a place that serves as a refuge for a thousand or more who seek to escape the repression. As The Suicide Museum opens, Dorfman is writing a detective novel based on his time at the embassy. Those who know the grounds and neighborhood will remember the gates and trees of the building, and be transported to the months when the military camped at its doors in order to deny entry to asylum-seekers.

Dr. Jose Quiroga, a physician who now works with victims of torture in Los Angeles, is at La Moneda on September 11, 1973, and is one of the last people to see Allende alive. He assures me that Allende killed himself in what he considers a heroic act. Quiroga is never mentioned in The Suicide Museum, but many others I know personally or whose names are part of shared histories, float in and out like an unpredictable Andean fog.

The publication of The Suicide Museum coincides with the 50th anniversary of the 1973 coup, which gave rise to the 17-year dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet.

The 50 years we mark in 2023 had a preamble that must include the approximately 1,000 days that Allende held the presidency, and that runs back to the time between his election and his formal swearing-in. To round out the picture, we should include his two failed presidential campaigns of 1958 and 1964, and of course the 30 years Allende served as a senator in the Chilean Congress.

In Spanish, 50 is cincuenta or sin cuenta — “countless.” The Suicide Museum relates myriad stories from the days before and after September 11, 1973. For a Chilean like me who lived and encountered many of the people, places, and events described within the plotlines, it’s like coming home to where things have been rearranged, but feel eerily familiar. Central to the novel is Allende’s suicide on the day of the coup, an act that some consider heroic and others might consider an act of cowardice. It has never mattered to me, because Allende would have lived if not for the treason and violence of those who tried to kill him. His death was the result of years of intervention by United States intelligence agencies and multinational corporations in the affairs of our country; the result of arms deals, military training, and exploitation of natural resources, the result of blind faith in Cold War hatred.

On the day I am born, Allende, at the time a practicing MD, visits my mother, Isabel Morel, at the Clinica Santa Maria in Santiago, located at the base of San Cristobal Hill and along the Mapocho River. He also visits another family, and as a result my mother meets Marilu Santa Cruz, her husband Cristian, and their newborn daughter, Paula.

At the time of my birth, my father is an economist and copper expert for the National Copper Department. Two months later he loses his job and is told he will never again find work in Chile because of his ties to Allende. We first relocate to Venezuela, but eventually he finds a job in Washington DC, working for the Inter-American Development Bank as does Paula’s father, Cristian Santa Cruz. The families become very close, and I attend Catholic school with Paula as a classmate. We are neighbors in a Maryland suburb just outside of Washington D.C. until Allende is elected president and our lives change.

My family would spend summers and vacations at a rural property in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, along the Shenandoah river outside of the small town of Shenandoah. Prior to the arrival of the English, these lands were hunting grounds for many native tribes, including the Iroquois and Shawnee nations.

It is September 4th, and I am running along the river. Down past the dam, the Shenandoah merges with the Potomac, where 100 years ago abolitionist John Brown attempted to catalyze a slave rebellion in the South by taking over the United States military arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Brown lost his life in the name of freedom. Frederick Douglass was asked to join Brown’s raiding party but considered it “suicidal,” and Harriet Tubman allegedly begged off.

I know the way and can jump the barbed wire quickly. A cow and calf are on the bank, and I watch for the herd because they can get skittish. As I sprint to the cemetery, I look back towards the river. The old headstones date back to before the Civil War, but others are from between 1861 and 1865.

I hear the honking as I run up to the house and stand in the gravel road watching the car kick up dust devils as my father speeds down the hill, revving the engine and blasting a rhythm on the horn. “He won! Ganamos! Gano el Chicho!” he cries, referring to Allende by his nickname.

My parents and uncle and aunt stay up all night, drinking vino tinto and beer (my uncle favors Pabst Blue Ribbon and long neck bottles), playing poker, smoking cigarettes, and listening to music. We kids don’t know it at the time, but this is to be our last summer in Virginia.

We play outside, catch fireflies, and tell stories. We like to walk along the road under the starlight and let our eyes get used to things until we can see almost everything in the dark. Yet some things cannot be seen, no matter how well one’s eyes adjust to the dark.

We finally return to Chile, and my father puts himself at the service of Allende’s Popular Unity government. Only a few months later, he is appointed as Chile’s Ambassador to the United States and we return and live at the Embassy residence. My father is called back to Chile in June 1973, to serve in a series of cabinet posts. First as Minister of Foreign Relations, then as Minister of the Interior. On September 11, 1973, he is Minister of Defense and has worked closely with General Pinochet, a man who all believe is loyal to the constitutionally elected government and to democratic processes.

Approximately one year after the coup, my father is released from Ritoque Prison Camp on the Central Coast. Most of his imprisonment has been on Dawson Island, a camp he and other prisoners are forced to build in the far south of Patagonia. The governor of Caracas, Venezuela, Diego Atria, negotiates his release. But in early 1975, after only a few months in Caracas, my family returns to the suburb in Maryland where we lived before Allende’s victory. Now, it’s a place of exile. The National Intelligence Directorate, DINA (Chile’s secret police), begins to make plans and track my father’s movements. It is there, that in 1976, they plant the bomb that kills my father. The explosion resonates along Embassy row like the Hawker Hunter jets that flew over our apartment in Santiago when they bombed the La Moneda Presidential Palace.

Allende’s death at La Moneda is a catalyst of memory that binds millions throughout the world attested by the thousands of events carried out not only in Chile but throughout the world now as we approach the anniversary of his death. After September 11th, 1973, I memorize the grid of downtown Santiago and the blocks from our apartment to La Moneda. In the days after my father is killed, Dorfman and family are part of a community that help etch the streets of DC into our memories as a form of restorative justice. Dorfman who was born in Argentina, is from a Russian Jewish family that later emigrated to the United Sates and afterwards, because of political tensions, to Chile. He understands, more than most, how individuals must create and claim their own belonging to places that were once foreign and unknown.

In The Suicide Museum, Dorfman describes the social process in Chile today, the reclamation of our nation through democratic practices and principles. In so doing, he asserts his place in Chile and its history, linking together the many places, people, and memories that make it possible.

Dinner at the White House, in the Lion’s Den

On September 21, 1976, when my father is killed along with Ronnie Karpen Moffitt, I catch a glimpse of the uniformed rescue squad and firemen as they hose down Massachusetts Avenue, washing the crime scene clean as bloody water flows towards underground channels. I want to understand the way the water flows down sewers, through channels along Rock Creek into the Potomac River and into the great Chesapeake Bay. I think of ocean currents somehow carrying my father towards the Pacific and south to the Chilean coast near Temuco, where he was born. The cliffs along the Virginia side of the Potomac River become the far bank of Santiago’s Mapocho River, which runs alongside the clinic where I was held by Allende on the day of my birth.

Dorfman crafts a world of nuanced sentiment and expanded belonging as we continue to reimagine the world according to Allende’s legacy, building the “great avenues” that “El Chicho” predicted we would “sooner rather than later” open for freedom. As one of the foremost authors of exile, he creates a map of experience that charts many geographies and historic moments. In one of the most moving passages of Dorfman’s novel, the author and a mysterious character, Joseph Hortha, hide in the Santa Inés cemetery in Viña Del Mar, the bustling seaside city lying one hour west of Santiago, where, in 2011, Allende’s remains are disinterred and transferred to a new coffin. As Dorfman watches, he thinks of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, and catches himself thinking of the Mississippi River, but the author is in Chile and he recognizes some of those who carry out the disinterment as old friends and colleagues.

As I read this book, I am caught in my own memories. I am at Chile’s national cemetery with a small group of people on the day the plain wooden casket holding Allende’s body is brought to Santiago from his unmarked grave in Santa Inés — the same casket Dorfman describes in his novel as falling apart when Allende’s remains are transferred into a fine new box.

At that moment in history, we do not know how the new Chilean government will navigate our transition to democracy, and our distrust of the police has not diminished. We hoist photos and flags while chanting slogans such as Allende Presente! but it still feels like we are taking chances. On that late afternoon, the crowd disperses quickly, blending with people on the street in the way we did during the dictatorship. As we wander home, the carabineros are swarming near the entrance of the cemetery and along the downtown corridor near La Moneda.

One month later, on Sept 4, 1990, a massive official funeral honors Allende in a long overdue national ceremony coordinated by Enrique Correa, the Secretary General of the Government, arguably the most important cabinet post. In the novel and in real life, during the years of exile, Correa and Dorfman are close friends. In the author’s descriptions of those who orchestrated our transition from Pinochet’s dictatorship, there are lessons concerning power and loyalty.

Dorfman is always generous with his words; he takes the time needed to flesh out his characters. No matter where in the story, opportunities arise for him to share thoughts on a wide array of subjects. Along the way, readers will come across models of masculinity, standards of physical ability, and ways of honoring the living and the dead. Even as the author contends with the remorse and guilt carried by survivors, he shares insights and lessons that transcend the particular histories of Chile and exile.

After his murder in 1976, my father’s remains are flown to Caracas, Venezuela, the result of an offer by the Venezuelan government that his remains be interred on Latin American soil until the day we might return them to Chile. In November 1992, my brother Jose flies to Caracas to exhume our father’s remains and place them in yet another coffin. His first burial had been in an impressive sarcophagus made of brushed stainless steel. Jose arrives at the hilltop cemetery with government representatives and is met by a team that will dig and transfer the remains into a new casket sent by the Chilean government. There is an audible whoosh when the steel casket is opened, as if the container has kept an airtight seal. My brother later tells us that the body looked exactly as it had in 1976. It is only when workers lift the corpse that he realizes the remains are light and dried out, “almost mummified.” Today, a large black volcanic rock marks my father’s burial site, which is located near Allende’s tomb. I imagine the location described by Dorfman in The Suicide Museum, where he and an eccentric humanitarian billionaire eavesdrop on history, and I feel the Chilean night, as though I am hiding in the shadows myself.

Allende’s funeral is held on the 4th of September, 1990, the 20th anniversary of his presidential victory. I have returned to California and am about to turn 31, when I learn that my partner at the time, Monica Perez Jimenez, is pregnant. My son Matias will grow up in neighborhoods where drug dealers carry weapons and police regularly stop and frisk us demanding indentification papers. He is one year old during the long hot summer of the LA uprisings that occur after Rodney King is severely beaten by LA police in 1992. On our corner, SWAT teams and helicopters communicate as shots ring out in staccato fashion. I am making art with incarcerated youth in juvenile prisons and camps to support my family. At the time, there are 40,000 to 50,000 youth serving time in Los Angeles County, the vast majority of whom are black, brown, and/or poor.

In the novel, after Dorfman leaves the Santa Inés cemetery, he remembers that on a visit to Viña Del Mar when he was seven years old, he and his father planted a tree somewhere in the city. His co-protagonist, Hortha, says that he also planted a tree when he was seven, but in a forest in Europe.

Hortha has made billions selling plastics but is now trying to make up for the damage he has done to humanity and nature. The memory of planting a tree, something that outlasts our short human life span, spurs him to share an epiphany with Dorfman: an outlandish scheme straight out of the mind of a messianic billionaire that until now has been kept secret. The Suicide Museum is in part about Hortha’s plan to change the history of the world.

Hortha, this über-smart billionaire who has helped bring the planet to ruin and has now repented, is not a likable figure. Yet through him, we are able to draw the line between the terrors of Nazi Germany and the horror of the death camps to the present day, when the sons and admirers of Nazis and fascism perpetuate the cult of Pinochet in Chile, and gain popularity using the same red-baiting propaganda mastered by Hitler and Joseph Goebbels.

I am disappointed in Hortha’s plan to create a Suicide Museum in answer to the precipice of the Anthropocene era; it is so farfetched that I feel like I’ve landed in a Vonnegut novel or at least a Borges narrative. As events progress, however, readers will realize that this is the intention of the author, for the novel does not peddle false promises and ultimately even in its fictions asks us to take on reality, sharp edges, risks, and all.

After the coup, I work for the former undersecretary of the Ministry of Foreign Relations in a small storefront in downtown Santiago, where we sell multicolored vessels, containers, and buckets made of Polypropylene, the thermoplastic polymer that on Dorfman’s pages fuels Hortha’s ego and bank account. Dorfman seems to know that certain themes and ideas will trigger memory, and bring readers back to personal reckonings.

As I read this novel, I remember my father also planted trees with his sons far from home at a place we called Chile Chico in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. As exiles do, my father and uncle recreated a piece of Chile in Virginia, amidst old mountains and farmland, near stands of Eastern hardwood. It is not the Mississippi, but rather the Shenandoah River that comes to mind as I read the novel. The Shenandoah flows into the Potomac River, which carries my father’s blood towards the great Chesapeake Bay onto Atlantic currents that mingle with Pacific waters as they round Cape Horn and are picked up by the Humboldt current that brings him home.

For a few years before our lives are immersed in the political events described so well by Dorfman, I live a hybrid boyhood, a blend of Lautaro and Tom Sawyer. (Lautaro is a figure from Chilean history. Enslaved as a child, Lautaro learns the ways of the Spanish and, as a Mapuche leader, becomes their fierce adversary. The Mapuche are a major group of indigenous people in Chile that fought Spanish and Chilean colonizers for 400 years). I find myself working for a farmer bailing hay, feeding cattle, and mucking out chicken coops. Both the writer and myself have bicultural identities and that is what interests most me about Dorfman’s novels. The Suicide Museum, a novel that is so personal, is written not in Spanish, but in English.

Dorfman’s novel is a farewell to previously held ideas of belonging: he has realized he is not “an exceptional exile who will return triumphantly” to save Chile. Yet those familiar with his work already know this about him. Dorfman is a thinker who has consistently challenged injustice and described exile while imagining new possibilities for identity.

The past always breaks into the present, Dorfman reminds us. Those who tell stories know this and use it to their advantage. Trees have memory, they will remember you like an elephant, like a rock; sing to them and they will hear you. In my small yard in Venice, California, I have an avocado tree planted with my son at a time when I am trying to “return” to a Chile that has changed beyond description. I can’t take my son to Chile and keep him there, so I return, much like Dorfman, to the familiar in-between of the United States…where our people die and where our children grow, create the landscapes of our imagination.

Dorfman teaches us that despite appearances, these places within, arising and retreating like the wind, play a role in determining our histories.

I find a tremendous loneliness in the novel. Dorfman shares names and events that I often carry like a last surviving carrier pigeon, because it is so uncommon to meet someone from my flock. Yet no matter how alone we feel, within geographical borders of a supposed nation or in the virtual space that we inhabit, we are not alone. Something that contains a co-mingling of the present and past can arise to remind us that we are seeds that will grow into trees with roots that reach beyond rivers, checkpoints, distance, and time.

Paula, whose family was also visited by Allende on the day we were both born, becomes a doctor in Santiago, and her mother Marilu returns to Chile to study and teach dance, as she had done before she married. In the early ’90s, after Pinochet has partially relinquished his power and I have returned to Chile, Marilu takes me to her dance class, taught by Joan Jara, the widow of Victor Jara, and for several months I study dance in Santiago and rent an art studio in Recoleta, a working-class neighborhood on the other side of the Mapocho River.

One night, a man violently attacks me during a verbal discussion by a visiting American artist. I call Paula and she tells me to meet her at the Clinica Alemana, where she sews my chin back together. I am glad she became a doctor, perhaps inspired by Dr. Salvador Allende, but our connections have occurred in our leavings and returnings; we have emerged with a shared knowledge of what it feels like to belong to several places at once. It’s a phenomena that Dorfman gives form to in his writing, and it serves as a Rosetta stone for understanding the past and the future.

On September 4, 1973, one week before the coup on September 11, I join hundreds of thousands on the streets to celebrate the third anniversary of Allende’s presidential victory. On September 5th, I turn 14. I am a short kid. I climb a traffic pole and perch precariously, listening to Allende address the crowd. It is the first time I experience a tingling in my scalp and a ringing in my ears. It has only happened a few times since, but decades later I recognize it as the ring of truth, and on that day I am sure that I am exactly where I need to be. As such, today an exquisite sense of belonging overcomes me as I read about the places and cities in Dorfman’s novel.

In 1971, we spend the summer on the beach on the Central Coast of Chile, where my great grandparents, my grandmother, and mother spent their summers in the past. I am 11 and it is the best summer of my life; I have a crush on a girl and also have a crew of friends. My father arrives from Santiago and tells us that on Saturday we will visit President Allende in Viña de Mar at the Palace of Cerro Castillo, the presidential summer residence.

On Saturday, we are looking sharp; we’ve shined our shoes and combed our hair with gomina hair pomade. As for my father and Chicho, they are dazzling. They seem to be cut from the same cloth: the president and my father both wear impeccable shirts and ties. They both smell like really good cologne. Chicho is very nice to us and makes jokes as we take pictures with him.

Asi que tu eres el Panchito, me acuerdo de ti y cuando naciste (So you are Panchito; I remember when you were born).

I will never forget the view of the Pacific as we stood with him.

The Kodak print from my dad’s Instamatic lives in a small silver frame, my brothers and myself with Allende against los cielos azulados, the blue skies referred to in the Chilean national anthem. The twisting coastal highway, the port of Valparaiso, sunlight on the hills as we drive back to Papudo, the smell of empanadas de marisco (shellfish) and Coca Cola…

At the end of it all, I am brought to tears of respect for what Dorfman ultimately shares. His courage to face the consequences of what has happened to our planet and his rekindling of the memory of Allende are complemented by the way he conveys the enigma of Hortha to his readers. Dorfman is a global writer at a time when we need his magnitude of understanding, as well as his gentle loyalty to roots, the Earth, and memory, which together have sustained the author’s lifelong belief in human beings and justice.

Dear cousin Pancho, Many thanks for this sensible article on Dorfman book that I will certainly read. Family memories come to me and the month I spent in your apartment and share your life until the moment it become prudent to leave to Switzerland. I admire your work since.

Francisco: this is absolutely fabulous! Thanks for weaving your history with Dorfman’s fictional mix. A truly impressive narrative!