Read online or grab a pdf at IranWire.

Malu Halasa

In Tehran, lies, rumors and misinformation circulate about the Covid-19 vaccine.

Some spread by Ayatollah Abbas Tabrizian maintain that the vaccine is a Western plot to turn people gay—a conspiracy theory widely reported in the anti-Iranian Arab press. Other falsehoods, which don’t make the news but are repeated regularly behind the walls of the city’s highrises, say that any vaccine administrated by the Iranian government would be water anyway. Or that the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca supplies, sent to the country by U.S. and U.K. governments and rejected outright by the country’s spiritual leader Ayatollah Khamenei, were confiscated by the Revolutionary Guards.

“Political culture remains ‘near-pathologically preoccupied with reinforcing its legitimacy and manufacturing or forcing the appearance of domestic consent.’ And this has made telling the truth about the life and death consequences of the virus all the more challenging, to say the least.”

The pandemic has been difficult for countries around the world. However, in Iran, religion has not been the only factor that complicates matters. According to IranWire’s report, Only the Trenches Have Changed: Health Policy and Practice in Iran during Covid-19, political culture remains “near-pathologically preoccupied with reinforcing its legitimacy and manufacturing or forcing the appearance of domestic consent.” And this has made telling the truth about the life and death consequences of the virus all the more challenging, to say the least.

Now a graphic novel joins IranWire’s on-going, in-depth reporting about the pandemic, from official reports and statements by public officials to short films and documentary and anecdotal evidence, some 300,000 words in Persian and English since last year.

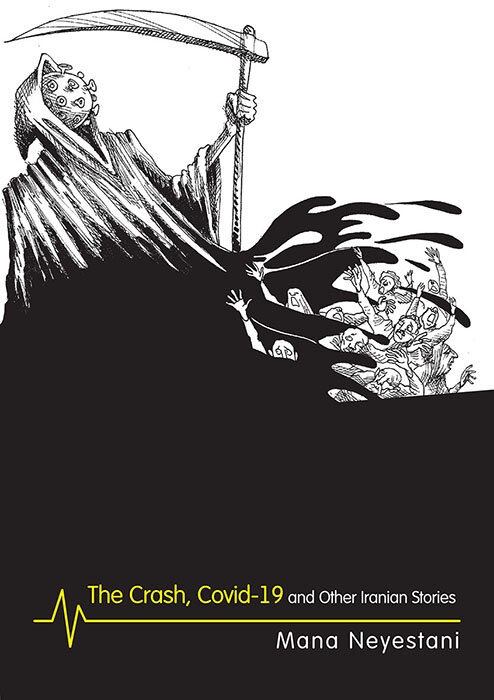

The Crash, Covid-19 and Other Iranian Stories by Mana Neyestani tells the story of four seemingly unconnected fictional lives that become intertwined due to the virus: a writer; a religious teacher in Qom; an investigative reporter and a nurse in a hospital intensive care ward. The graphic novel takes place against the backdrop of forgotten news events from last year that upended Iranian society and continue to do so today.

Neyestani, an editorial cartoonist, is well aware of the restrictive nature of telling a story in a single drawing. In the interview, which accompanies the free download of The Crash, he says, “In a cartoon, we have to introduce all the characters in one frame: both the killer and the victim … There isn’t enough time for in-depth characterization.”

Neyestani, jailed in Evin prison in 2006 for an editorial cartoon, recounted his experiences in the graphic novel, An Iranian Metamorphosis that was written and published, in 2014, after he went into exile in France.

Feelings of Collective Exhaustion

Many Iranian graphic novels, including the groundbreaking Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, grapple with that pivotal moment in Iranian history when the country turned from a secular to a religious society. The Crash is also rooted in a turbulent past, the following 40 grueling years, which provides the emotional tenor of Neyestani’s story.

The cartoonist explains, “Until 20 years ago, I think many Iranians believed positive change and reform could take place. Unfortunately the government was ruthless and didn’t take one step toward meeting their demands. In the waves of protest that have taken place … in 1999, 2009, 2018 and 2019, we see frustration and anger. Each time they are confronted with a hammer-blow of repression and suffocation by the government, and the windows of hope are closed. This has created a feeling of collective exhaustion.” A longer interview, edited into twelve, approximately two-minute segments, can also be seen on YouTube.

The Crash begins with the despairing writer’s continuing nightmares of the January 8, 2020 shooting down of International Airlines Flight 752, in which 82 Iranians and 63 Canadians lost their lives. It was a revenge attack by the Revolutionary Guards that went wrong, after the U.S. assassination of General Qassem Soleimani in Iraq five days before.

The writer, who lost his grown daughter Hengameh on the flight, can barely watch the evening news about the upcoming parliamentary elections, which has taken precedence over a deadly virus coming from China. In reality, Neyestani’s brother, the political cartoonist Touka Neyestani, lost his fiancé who also died in the plane crash.

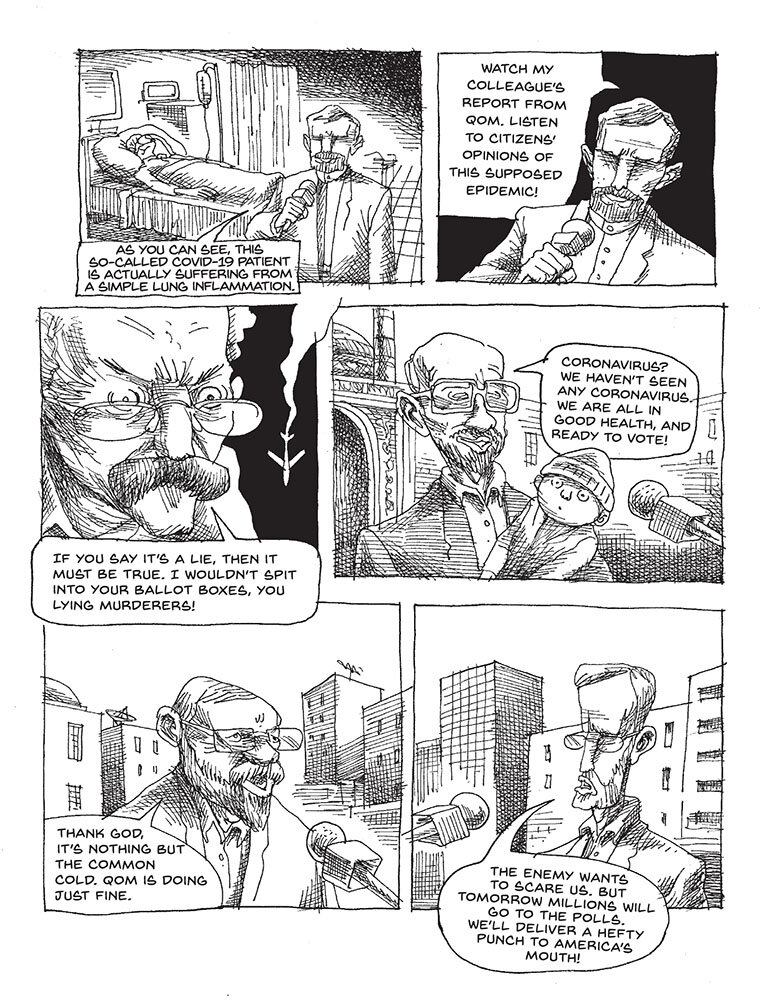

On the opposite end of the political spectrum in the story is a religious teacher from Qom, who believes the Islamic way of life for his little daughter, Fatemeh, is under threat, and that any criticism of “our noble guards” is a conspiracy by the Israelis and Saudis. The internal dialogue is the novel’s most powerful device. It is something all four characters share, despite their obvious differences—a private refuge they must resort to when the outside world of a totalitarian system is full of lies, role-playing and fear-mongering. Despite news of the virus, the religious teacher joins thousands of others, in long queues and crowded rooms to vote, with no social distancing or masks in the country’s parliamentary elections on February 21.

These elections were in fact the second of two real-life “superspreader” events that took place in Iran last year. The first were the rallies and marches commemorating the 41st anniversary of the Iranian Revolution. By the time 34 million Iranians went to the polls to vote two weeks later, regime officials who had been vociferous in denying the danger and spread of the virus were getting sick, in public.

Reading State Media

The journalist in the graphic novel, Saeed Madai, is introduced as an astute reader of state media. Sitting at his desk at home, he is analyzing a newspaper photograph, which shows the traditional “Meeting of the Exalted Leader.”

Despite Khamenei’s dismissal of the virus as “rumor-mongering,” his followers were not allowed to kiss his hand or throng around him, as they would normally do on such occasions. Madai draws a line to note the enforced distance between the supreme leader on his throne and his followers on their knees. Outraged, the journalist can no longer stay silent and live-streams on Instagram, during which he details the lies of the regime, the failure to stop flights to and from China, as well as the denial of the rising numbers of those treated and dying in hospital.

For the character of Madai, Neyestani had been inspired by journalists who have run afoul of the Iranian authorities: Mohammad Mossaed, who was jailed in 2019, for a tweet; and Mahmoud Shahriari, a television presenter arrested in April last year, after he spoke about government cover-up and spread of the coronavirus, charges he too had broadcast from his home via Instagram.

In the comic, after First Deputy Health Minister Iraj Harirchi ridicules the idea of quarantines as “belonging to the medieval era,” journalist Madai exclaims: “Quarantine is ‘Medieval?’ In our country we execute and flog prisoners in public and cut off the fingers of thieves.”

There were more lies to come from the religious establishment, which suggested Qur’anic prayers and pilgrimages during Ashura, even the injection of violet oil into the anus, could prevent coronavirus.

Interestingly, Neyestani notes that it was only when the number of deaths started rising in America did the Iranian officials admit to increased death tolls, as though Iran always has to be in competition with the Great Satan. Meanwhile his drawings of mullahs and the virus with its characteristic spikes embedded in their turbans bounce across the page.

Divide & Rule

In the graphic novel, the fourth character that readers meet is the intensive care nurse, who captures the real tragedy of Iran. Mojgan watches Madai’s live broadcast on Instagram, and wonders why he is even allowed to broadcast. If he is permitted to by the regime, nothing he says can be trusted despite the fact he presents himself as a dissident voice.

With nurse Mojgan, Neyestani identifies one of the successes of authoritarian regimes in spreading suspicion, and using “divide and rule” tactics so that people end up not giving credence to those who are “on their side.”

However, Mojgan doesn’t have the time to sit around her bedroom, smoke cigarettes and worry; she has to get ready for work. At her hospital during the early days of the virus, one of the doctors told her not to wear a mask because it “scares” patients. As a result doctors and nurses have died. Mojgan is frightened of catching the disease, and dreams of leaving the country. Her story reflects the true to life situation for many Iranian health professionals who hope to emigrate abroad. Some nurses, in groups, have already left.

The story comes full circle, when the virus ignores class or political persuasion, and Mojgan’s dying patients include, ironically, two polar opposites of Iranian society, now lying side-by-side in their hospital beds: the writer and the religious teacher. At the end of a harrowing shift, she sees from a phone alert that the journalist Madai had been arrested. So he wasn’t a regime lackey after all.

The graphic novel ends with the mourning ceremonies in the Imam Khomeini Prayer Hall, not for the thousands of Iranians who died from the Covid-19 but for the 40th day of Imam Hossein’s martyrdom from over 1,400 years ago.

Powerful and thought provoking, The Crash lays bare the hypocrisy of the regime. Yet, satire alone will not insure the regime’s downfall. Despite this, artists and journalists under great personal danger to themselves remain committed in speaking truth to power. In the meantime, ordinary Iranians “crushed under the pressure of poverty, inflation, sanctions and a thousand other miseries … learned to wear masks in order to survive … Everyone has another mask” – even under the ones they wear as protection against the virus.