In a divided country/divided island, the ruins of memory inspire artists to contemplate the temporal reality of life in an age of violent conflict.

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

“There’s no such a thing as a good war” is what an elderly woman tells Turkish Cypriot soldier Bulut, in Lebanese artist Ali Cherri’s short film The Watchman (2023) — a statement that certainly doesn’t need more evidence today. She’s invited him indoors for a coffee during his daily patrol, and recounts the events of how she named a son after a fallen martyr, whose name appeared in the local newspaper. Afterwards, she became afraid that her son would be killed as well, and decided not to send him to the army.

We don’t know what happened to her son, or what his name was, but the real story underlying this fictional plot is one of Europe’s most protracted conflicts. The Cyprus question goes back to the political struggles for hegemony in the region between Britain and the Ottoman Empire at the end of the 19th century, but more specifically refers to the crisis of 1963-1964 and the 1974 Cypriot coup d’état, sponsored by the Greek military, followed by the Turkish invasion. The island remains divided between the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish-controlled area on the northern part of the island.

Today Nicosia is arguably the world’s last divided capital. The thin green line drawn in pencil by British General Peter Young in 1963 from one end of the Venetian walls to the other, at best a dozen meters, in order to stop fighting between the Cypriot Greek and Turkish communities, was extended to cover the entire island after the Turkish invasion in 1974, and is now about 180 kilometers long. In a double exodus, Greek Cypriots were forced out of Kyrenia, Famagusta, and other now occupied areas, towards the south, while Turkish Cypriots were displaced to the self-proclaimed Turkish Republic of North Cyprus, to this day recognized only by Turkey.

In the year 2024, when the Cyprus question will reach half a century since the final fragmentation of the island, ethnic conflict, occupation and displacement are hardly political innovations — Nagorno-Karabakh and the latest carnage in Gaza are only the most recent examples in an incredibly violent decade.

What is striking about Cyprus is not conflict but rather the lasting persistence of the afterlives of violence and the way in which these historical events become political, and ultimately human conditions. Since 1974, there hasn’t been one inch of progress in negotiations between Greek and Turkish Cypriots other than the re-opening of the checkpoints in 2003, allowing Cypriots from both sides to visit other parts of the island, in spite of several rounds of negotiations up to a freeze in talks since 2020. It is estimated that a third of the residents of either side have never crossed the dividing line.

Ali Cherri told The Markaz Review about his work around geographies of violence that began in his native Lebanon but that has now extended to the wider region: “The Watchman is a part of this long project, including my films The Disquiet (2013), The Digger (2015) and The Dam (2022), looking at how socio-economic and political violence disseminate into the landscape, and on people’s bodies.”

Cyprus has never been too far from the historical imagination of Lebanon and the wider Mediterranean region, since the Bronze Age kingdom of Alashiya rose on the island in the 16th century BCE, as a major source of copper for Ancient Egypt and Ugarit. In the near present, Cyprus has been an “echo-chamber” of Lebanon, with conflicts in the region often resonating on the island: The civil war in Lebanon led to an influx of refugees in Cyprus that transformed the economy of the island, and even today, recently displaced peoples from the Middle East continue to shape its demography. There are also other parallels between Cyprus and Lebanon: Unrecognized borders, occupations, division lines, and the conditions they have helped create.

Cherri’s The Watchman is not a documentary about the conflict but rather, a many-layered visual essay — dialogues are sparse — on the condition of the border itself and the figure of the guard; this male subject, militarily constructed, perpetually waiting, waiting for an enemy, often imaginary, that might or might not arrive. As a part of Cherri’s solo exhibition Dreamless Night at GAMeC, in Bergamo, curated by Alessandro Rabottini and Leonardo Bigazzi, the film is set in the village of Louroujina, known as Akıncılar in Turkish, located within a salient that marks the southernmost pocket of occupied Northern Cyprus, separated from the Greek Cypriot village of Lympia, only by the UN Buffer Zone, casting light on the difficulties of erecting a physical border where none existed, amongst heterogeneous populations.

The artist told TMR about the process of creating the film in Cyprus: “When I decided to start working in Cyprus I didn’t have an exact idea for the film, which is how I usually work. I decide a location, a geography, a landscape, and I try to get inspired from my visit and the time I spend there. When I went to Northern Cyprus I knew I just wanted to go along the border and it was upon my arrival to Louroujina that I knew this is where the film should take place, because of the geopolitical situation, but also because of the village being almost completely deserted, except for a few elderly people still living there.”

The protagonist of the film is a young Turkish Cypriot soldier, Sergeant Bulut (played by first-time actor Halil Ersev Gökçek), stationed at a watchtower in Akıncılar, guarding the border of the unrecognized republic, looking out for the enemy. He seems hypnotized by the barren landscape that is apparently pregnant with danger; his gaze fixed and his eyes bloodshot. Yet as the film tells us, there hasn’t been any significant change in the dividing line since 1974. The landscape that Bulut is surveying in the film, however, in reality, is neither in Akıncılar nor in Lympia. It is rather the nearby village of Petrofani, known as Esendağ in Turkish, inhabited by Turkish Cypriots until 1974, and now completely abandoned, near the Greek Cypriot village of Atheniou. Louroujina and Petrofani indeed share a past: In December 1963, Turkish Cypriots evacuated the village and sought refuge in Louroujina, but returned in 1964. After August 1974, the majority of Petrofani’s Turkish Cypriots fled to the north of the island and settled in Düzova.

Strange things happen to Bulut at this watchtower, overlooking Petrofani: He begins to see lights flickering in the distance at night, and as these maddening visions become an obsession, we begin to doubt his sanity. But it is not only us: In the film, his superiors instruct him to stop reporting these uncertain appearances.

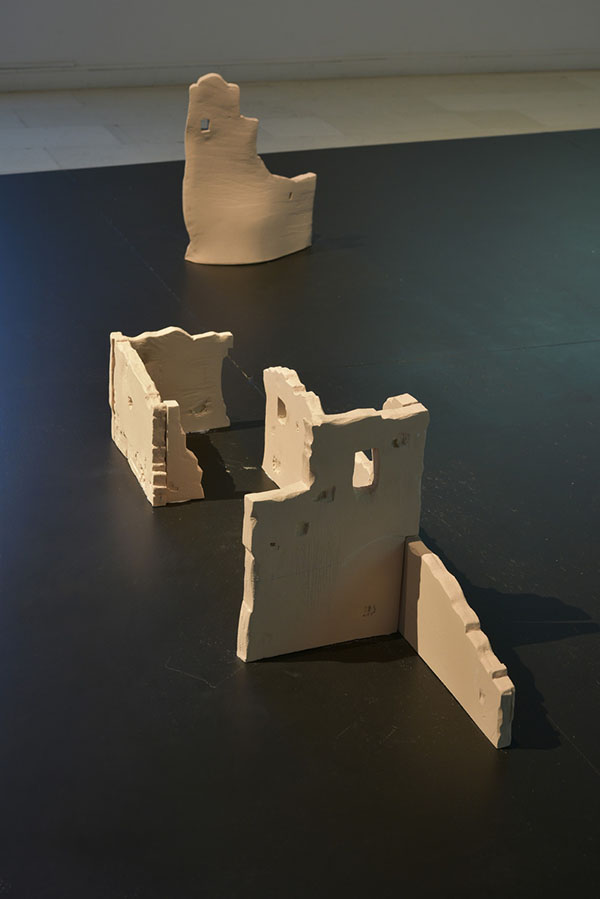

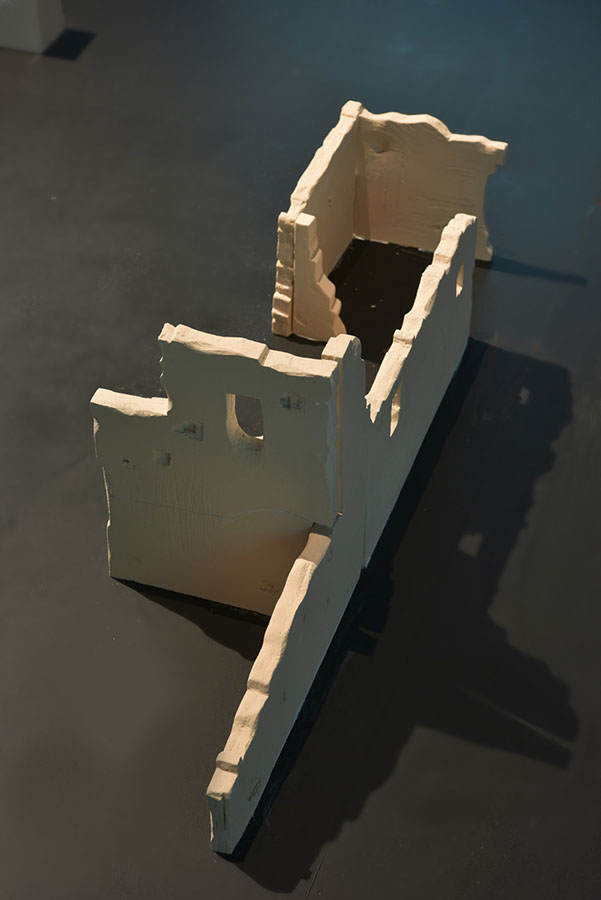

The Watchman was not the first artistic gaze at Petrofani: Cypriot artist Vicky Pericleous began researching Petrofani over a decade ago, when she accidentally came across the site while driving around the island. In her later work, the installation A Minimum of a Visible World (2018), she reconstructed the remains of Petrofani in collaboration with architect Eleni Loizou and ceramic artist Vassos Demitriou, himself a refugee from Ammochostos in 1974, using archival material such as photographs, videos and architectural drawings. Footage of the village environs recorded by CCTV cameras were projected onto the walls of the exhibition space, producing the feeling of a space that is impermanent and subjective, and ultimately constructed by the viewer.

In the exhibition The Presence of Absence, or the Catastrophe Theory (2018), curated by Cathryn Drake at NiMAC in Nicosia, where Pericleous’ installation was first presented, artists from the fragmented region surrounding Cyprus reflected on the limits of European cosmopolitanism and the Enlightenment concept of universalism, from the perspective of modern states formerly united under the Ottoman Empire, and now the set of diverse scenarios of ethnic strife, rupture and conflict. In these new national states, formed largely by freshly assembled myths, traumatic events of the past continue to lurk in the background, and are either instrumentalized and then monumentalized as the unreachable historical past, or simply erased from public view in an attempt to transform collective memory to match the straight lines of modern maps and define modern citizenship as the sole arbiter of personal identity.

During the previous decade, Pericleous was working on expanding the visual field of Cyprus’ political geography, especially following the reopening of the checkpoints in 2003, in a series of collages that rearranged fragments of the topography and architecture of the island into chaotic temporalities, as in the exhibition Nowhere and Elsewhere (2012) at Omicron Gallery, giving the impression that different elements were out of balance and on the verge of collapse. There’s an uncanny but discrete similarity here with Cherri’s The Watchman in its attempt to unearth invisible traces of violence that have become embedded in the landscape: They both produce liminal spaces in the imagination that transgress reality and often supersede it. The crucial image here is not one of immediate catastrophe or violent destruction, but something far more poisonous. It is about traces of violence that remain not fully present, often latent, and that have completely disfigured the landscape and its inhabitants. This trace is a sign that the violence hasn’t disappeared but rather entered a dormant stage, while still operational, slowly eroding places and populations, and it could potentially reemerge.

A car journey I took from Larnaca to Petrofani with Vicky Pericleous, at the end of 2023, revealed the geographical opaqueness of this borderland around the irregular UN Buffer Zone: The lack of road signage and street lights leading to the village, a nondescript site that could be anywhere or anything; an archaeological site, an abandoned village, an unfinished construction site, or the site of a violent expulsion. The closeness of the separation fence shapeshifting around the landscape like a snake, sometimes only a few meters from the road and sometimes remote in the distance, the combination of overgrown nature and emptiness, they are always symbols not only of abandonment but of latent danger. These potent symbols make the visitor to this no man’s land aware of a void that has been emptied out not only of people, but also of memory and shut off into a state of permanent interruption.

Petrofani has been either progressively demolished or simply left to collapse, in order to make space for cattle whose muffled sounds reverberate in nearby barns, since Pericleous first visited over a decade ago. The situation seems to have worsened in recent months, even since Cherri’s film was shot at the location. Perhaps it will disappear completely, and in the absence of public memory for the heritage of Turkish Cypriots in Cyprus (a situation that is reciprocated with the heritage of Greek Cypriots in the north), not even a sign will stand in its place. Perhaps Pericleous’ architectural models and Cherri’s videography will become its only public memory, which will then acquire a ghostly quality.

In our conversation, Pericleous worried that these erasures have become a recurring pattern in Cyprus and that in fact it is a phenomenon happening on a wider scale all over the global south: “These erasures, which in many cases remain invisible or go unnoticed, might seem irrelevant, but could provide us with an understanding of the spatial manifestations of new forms of colonialism,” she said. Pericleous refers not simply to an abandoned village in the Cypriot hinterland, but to a major development spree all over Cyprus and the wider region, reorganizing urban and rural spaces that witnessed conflict into luxury towns, displacing entire communities and erasing painful memories.

At the end of Cherri’s The Watchman, we are confronted with the imaginary ghosts of Petrofani that emerge out of this political void: Obsessed with the possibility of an enemy attack, Bulut musters up courage to investigate the phenomenon of the appearances now turned into human-like shadows (we don’t know whether the vision is real or not), and finds himself face to face with an army of ghost soldiers whose eyes have been shut forever — and who speak in an incomprehensible tongue. It is as if these revenants have fallen into an eternal sleep, and have come to either lure or warn Bulut. He responds to them: “And what would happen to me if I followed you? Will I ever come back?” The film ends without resolution, and it is left for us to imagine whether the ghost is a metaphor for the unwanted foreign enemy, or a memory of the soldiers that died at the now sterile border, or whether it is Bulut who becomes a revenant himself.

There are a number of sculptural metaphors omnipresent in Cherri’s exhibition Dreamless Night, that connect the film with the geographical, political and ideological constitution of violence. The oversized clay warriors in a lonely embrace with their rifles, in “Wake Up Soldiers, Open Your Eyes” (2023), in reference to a sentence carved in wood on the inside of Bulut’s watchtower, recall here his recent exhibition Humble and Quiet and Soothing as Mud, at the Swiss Institute in New York, drawing on mud as a primeval material in creation myths and foundational narratives.

Cherri spoke about the double symbolism in his use of mud in Dreamless Night: “The use of mud of course started out from my research about archaeology; its capacity for conservation and something that encapsulates the memory of the past. It’s the materiality of the imagination, how from mud we have created all these mythological creatures and our founding mythologies. In the case of the soldiers, the mythological figure of the soldier is a construct built out of ideology, a symbol of force and strength that should give you a feeling of security. But a soldier of mud is a way to show the fragility of the concept, something that you feel could just collapse in front of you.” The soldiers here are at the same time fragile ephemeral earth and sempiternal ghosts, without a specific face or identity, trapped in a never ending wait, outside of the borders of time.

This fragility and risk of collapse that Ali Cherri describes through the figure of the mud soldier, is echoed closely by Vicky Pericleous’ reflections about architecture and landscapes in Cyprus, after a decade of engagement with Petrofani: “At first sight, everything seems to maintain a spatial coherence. But as the viewer gets closer, all the diverse layers, fragments and spatiotemporal crossings, become exposed. These new geographies that move from the actual to the imaginary, surpass spatial and temporal hierarchies which suggest the idea of a continuous spatial becoming. But one which could easily collapse. Most of the places I’ve been documenting and that re-appeared in those collages and sculptural models in my work have either changed over the years or disappeared.”

Cherri’s waiting soldier, constantly watching out, is accordingly not only a temporal but a spatial experience, therefore redefining the afterlives of violence not simply as events but also as a kind of inertia that has acquired a physical presence and grown into an interruption that bends the continuity between places, memories and our experience of time. This interruption, the void, is neither empty nor solid, but a viscous substance that oozes out and contaminates all the multiple pasts and presents of a locale, which in my mind, is the political experience of the colonial present as a system, rather than a period in time. The colonial present in Cyprus is a presence embodied not only in the 180km division line between north and south, but constitutes a pluridimensional grid that fragments the island temporally and spatially from all directions: Checkpoints, British sovereign areas, buffer zones, fenced abandoned villages side by side with the new settlements of its former dwellers, or a seaside casino overlooking a ghost town.

But as Cherri and Pericleous know, these fragmented spaces are not absolute and remain porous to the unpredictable return not only of violence, but also of memory. In a remote location like Petrofani, we can witness the latency of memory: “It moves at a very slow pace, in relation to other cultural ecosystems, while collapsing and being taken over by nature,” Pericleous says. “At the same time, it has become a shelter for birds and a farming site. Here lies the paradox. The site, though silenced and very distant from the interests of the public, voices out different, unheard and suppressed narratives about structures of power, contested territories, and economic exploitation; it has developed into a dynamic ecosystem of human and non-human activities.” Accordingly, Pericleous placed a replica of a 1960s purpose-built pigeon house found in Paphos among the miniature ruins of Petrofani, in her A Minimum of a Visible World (2018), given that parts of the village became an avian habitat, foregrounding a tension between modernist ideals and the agency of a ruin.

With the ongoing disappearance of the village ruins, the birds have begun to flock elsewhere, not being restricted by fences or UN maps. There’s a soothing avian symbolism in Cherri’s The Watchman, that connects his fictional plot set in Louroujina and Petrofani, with this agency of a ruin and the non-human ecologies of an abandoned site. Birds become in the film a device for measuring time, as Sergeant Bulut keeps a toll of dead robins that accidentally smash into the watchtower’s glass, and he carefully buries one of the colorful birds, wrapped in paper. Cherri explains his intention: “I wanted this watchtower to be something that in a way obstructs nature, something that birds hit during their flight, a kind of artificial obstruction. Nature is present and it also starts to take over.” The condition of the border affects not only peoples, but also landscapes, buildings and all living beings. It affects everything.

One of the main questions asked by the exhibition The Presence of Absence, or the Catastrophe Theory back in 2018 in Nicosia, was whether conflict causes the formation of borders, or is it the other way around? The border itself is a form of violence. Ali Cherri’s observer gaze, with the privileged vantage point of otherness and grounded in postcolonial conflicts, might appear sometimes obvious or redundant to a Cypriot audience, often inured to this violent reality by the sheer force of habit. But this distance also uncovers the temporal depth of the border; a violence that continues to be operational even long after force is no longer present.

The division lines erected between north and south can often appear imaginary from the perspective of Nicosia’s continuous architecture and the rather innocuous demilitarized checkpoints, and in fact Cypriot citizens can cross back and forth at will (even if many never have). But zooming out to the hinterland rapidly reveals the vast empty spaces that divide a country still scarred, kilometers of interruption, continuous displacement and the impossibility of lasting peace under conditions of permanent military vigilance of the other. The fiction of the enemy is often stronger and more monumental than the tenuous border itself. Ali Cherri’s The Watchman is a film not necessarily about Cyprus, but rather about our global moment of increasing hostility and heightened borders that might in fact produce a violence more lasting than any conflict: “What we’re seeing today really illustrates this idea, how we capture and take in all this violence that we’re seeing into our bodies and we also take it onto the earth and the landscape, so it’s a way of retracing these histories of violence through observation of their material manifestations on the land and on people.”

Ali Cherri’s Dreamless Night is on view at GAMeC, Bergamo, through Jan. 14, 2024, and will be on view at FRAC Bretagne, from Feb. 10 through May 19, 2024. His exhibition Humble and Quiet and Soothing as Mud was on view at the Swiss Institute, New York, from Sept. 13, 2023 through Jan. 7, 2024. The exhibition The Presence of Absence, or the Catastrophe Theory, featuring Vicky Pericleous’ work was on show at NiMAC, Nicosia, from Jan. 16-April 14, 2018.