Over 1,000 years ago, the great Persian poet Ferdowsi recounted the legend of the tyrant Zahhāk, a cruel ruler who conquers Iran and who has serpents growing out of his shoulders…

Omid Arabian

The tale of Zahhāk, a young prince who is seduced by the devil and transformed into an all-powerful tyrant with two insatiable snakes growing from his shoulders, is among the best-known chapters of the great Persian epic poem Shāhnameh (The Book of Kings). Written by the master poet Abu’l Qāsem Ferdowsi in the 11th century C.E., Shāhnameh is a multilayered masterpiece that feels both fantastical and relatable, specific in detail and universal in its themes and scope. For much of the epic’s initial phase, commonly called the Mythical Age, Ferdowsi draws on Zoroastrian source material including the sacred text Avesta and its later companion texts, Dēnkard and Bundahishn. However, Ferdowsi puts his own unmistakable stamp on ancient myths, altering them in ways that allow him to offer deep insight into the nature and behavior of people and society. In the process he carves out a unique space that straddles mythology, sociology, and psychology. In his re-telling of the Zahhāk tale, Ferdowsi masterfully transforms an extant demonological myth into an etiological study of human tyranny and its eventual downfall.

In the Zoroastrian cosmology, the world is the site of an epic, ongoing struggle between two entities: the creator deity Ahurā Mazda (“Lord Wisdom”) and his main adversary Angra Mainyu (“Destructive Spirit”). Similarly, in Shāhnameh, the early plot is driven by the struggle between two broadly-painted forces: on one side are Kiumars, the first king and his successors; on the other side are Ahriman (Middle-Persian name for Angra-Mainyu) and his descendants, the Dīvs. The earliest stages of this struggle involve direct confrontations between the two sides and their armies, battles that take place in a relatively primitivistic environment. But as Shāhnameh moves forward, the simple dualistic nature of the story evolves, becoming increasingly nuanced and complex. The kings that succeed Kiumars must manage a world of ever-growing complications. Their foremost asset in this context is farr – loosely translated as “Divine Glory.” Farr also originates in the Avesta, where it is a magic force or power of a luminous and fiery nature belonging to the gods. In Shāhnameh, farr is a quality that connects the kings to the universal creator; it provides the kings with power, and with guidance to use this power virtuously.

One of those kings who is fully endowed with farr is Jamšid, the immediate predecessor of Zahhāk. Jamšid rules over the mytho-historical land called Iran-Zamin, and his reign is characterized by the gifts and skills that he bestows upon the kingdom: medicine, fragrance, weaving, extraction of gems, and many more. The Dīvs are under his thumb and serve him as builders of castles and palaces. Jamšid’s world is at the height of wellness, prosperity, and peace. All of this is by virtue of his farr, his connection to the highest power. In effect, Jamšid functions as a channel for divine wisdom and benevolence — he receives it from the creator and bestows it upon his people.

Ferdowsi writes:

The world was at peace by virtue of the triumphant Jamšid

as he continually received messages from the Divine.

But — at the height of his power and glory, Jamšid loses sight of this divine connection, and becomes wrapped up in a vanity that borders on narcissism. Once he sees himself as the sole creator of all that is great and good, his farr immediately begins to wane, and so does his power. As a result, chaos and turmoil reign in his kingdom.

At this point Ferdowsi pauses the tale of Jamšid and takes us to the land of Tāziān, (a term that was used by Iranians to refer to Arabs.) In this land rules a king named Mardās, who is described by Ferdowsi as god-fearing. Mardās has a son named Zahhāk, who the poet says “has not benefited from love.” Ferdowsi further describes Zahhāk as impetuous, impulsive, unwise, and corrupt. Zahhāk owns 10,000 horses, and “spends most of his days in the saddle, seeking grandiosity for himself.” In modern terms, one could say that the absence of love creates a void in Zahhāk — and he is ensnared by a driving quest to fill that void with more and more of what the material world deems valuable: fame, status, power.

As such, Zahhāk now becomes fertile ground for evil. His neediness and insatiable want seem to serve as an invitation for Eblis (an Arabic name for the devil), who comes to Zahhāk one day at dawn. Shāhnameh previously referred to the devil by the Zoroastrian name Ahriman, and the change of name has prompted speculation about Ferdowsi’s motives. Some have argued that this switch (as well as Ferdowsi’s casting of Zahhāk as a Tāzi) is a not-so-veiled reference to the Arab invasion of Iran, which happened some three centuries before Ferdowsi’s birth in 940. But insight can also be found by examining the etymology of the word “Eblis.” Eblis is rooted in the Greek diabolos (from which we get the word “devil”) — bolos from ballein (“to throw”) and dia as a prefix meaning apart, in two different directions. This notion of being thrown apart — separated, divided, estranged — is integral to Ferdowsi’s characterization of Zahhāk, and shows up thematically well before Eblis approaches Zahhāk in his tale. Jamšid is estranged from his divine connection and his farr. Zahhāk’s father Mardās is estranged from his god and lives in fear of it; and Zahhāk is doubly estranged — both from his father (having received no love from him) and from himself (desperate to be someone other than who he already is).

But more so than his choice of name, it’s Ferdowsi’s rendering of Eblis’s character and modus operandi that highlights how he re-conceptualizes the Zoroastrian notion of evil. Here the devil is not a demonological character doing battle with gods and angels, but a force that tempts, recruits, and harnesses susceptible humans to carry out his own agenda. Ferdowsi’s Eblis plays the long game: he takes hold of Zahhāk in three stages, progressively separating, dividing, and alienating him. At each stage, Eblis changes his appearance and plays a different role, in human disguise. He first appears as a friendly sage, offering Zahhāk great knowledge — in exchange for a pledge of allegiance. Zahhāk is presented with a choice and, in his desperation to be more than who he is, surrenders his will to Eblis. He agrees to do everything Eblis tells him to do. Once Zahhāk is separated from his own free will and sovereignty, Eblis proposes that Zahhāk kill his father Mardās, as a way to kick-start the young prince’s ascent to the throne of Tāziān. When Zahhāk balks at this idea, Eblis offers to do the deed himself, and merely asks for Zahhāk’s silence — to which Zahhāk eventually agrees. His silence is an act of complicity in the murder of his father, and shows Zahhāk’s estrangement from his own compassion and conscience.

Zahhāk becomes King of Tāziān, and Eblis reappears as a renowned chef, offering his services. Zahhāk hands Eblis the keys to his royal kitchen in what amounts to a second act of surrendering sovereignty. In Shāhnameh Eblis is the first to prepare meals from the flesh and blood of animals; and as Zahhāk feasts on these he becomes increasingly vicious and bloodthirsty, taking on the characteristics of a predator and falling further away from his humanity. Eblis then asks to kiss Zahhāk’s shoulders as a gesture of great respect and honor, and Zahhāk grants the wish. At that moment Eblis vanishes, and from Zahhak’s shoulders two fearsome snakes sprout out, each as thick as a tree branch.

Shocked and distressed, Zahhāk casts about for a remedy, to no avail. At last Eblis appears for a third time, disguised as a doctor, and offers a solution (albeit to a problem he himself created). He prescribes that the snakes be kept calm with their proper food, specifically human brains (in Persian, maghz), until they eventually die. And so it is that every day, two innocent youths are captured and killed, their brains fed to Zahhāk’s snakes.

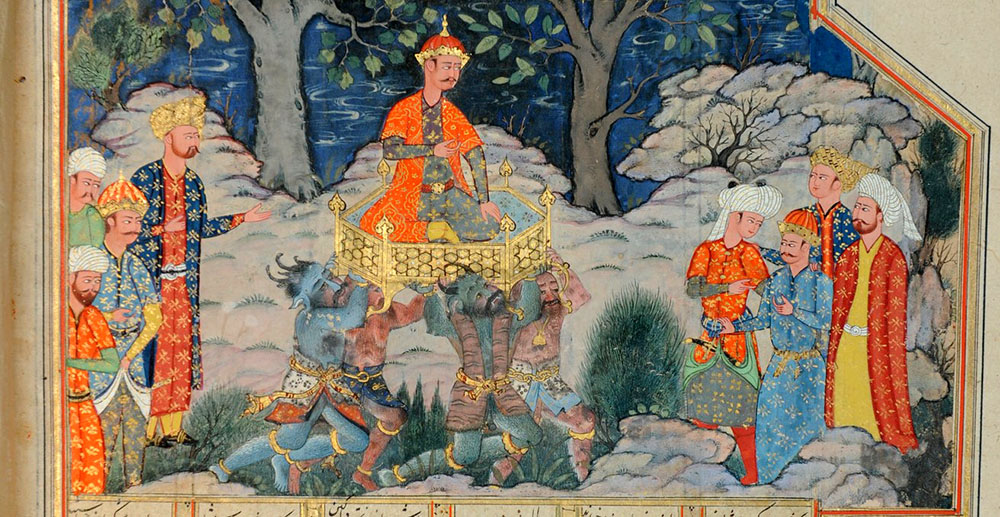

Now, Ferdowsi takes us back to Iran-Zamin where Jamšid’s farr is totally depleted, and the people long for a new leader to fill the power vacuum — a strongman who can rule with an iron fist and bring an end to all the turmoil. A delegation is sent to the land of Tāziān, inviting the fearsome Zahhāk — the Serpent King — to become the new king of Iran-Zamin. By rendering Zahhāk’s ultimate ascent as an act of selection, Ferdowsi illustrates the human propensity to make catastrophic and ultimately self-destructive choices, especially in times of upheaval and uncertainty.

Zoroastrian Roots

The Avesta, the primary collection of Zoroastrian religious texts, tells of a creature named Aži-Dahāk — a compound of aži (“snake/serpent”) and dahāk (that which stings). Aži-Dahāk is a dragon-like, three-headed creature with three mouths, six eyes, and 10,000 tricks up its sleeve. It has been created by Ahriman to battle alongside the forces of Ahurā Mazda and depopulate the world.

As with any legend, the story of Aži-Dahāk has changed as it has been passed down through the centuries; elements have been added and/or moved around. Ferdowsi brings his own powerful insights into human character and behavior, and masterfully blends them into the mythos. He re-imagines the fantastical monster Aži-Dahāk as the prince Zahhāk — a relatable human being afflicted with prototypical human wants and shortcomings.

Before Zahhāk, the kings of Shāhnameh confront Ahriman and his minions head-to-head, as enemies, in physical battles; but Zahhāk is the first character who in effect forms a mutual relationship with a dark force, and eventually internalizes it. Zahhāk now becomes a tool, a surrogate, a proxy for evil, carrying out Eblis’s project of taking over the world and slowly destroying humanity. As such, Ferdowsi’s version of the Zahhāk tale is really a tale of haunting, of possession.

Within the Book of Kings, Zahhāk becomes the epitome of the anti-king; he is a creature of many vices in a tale that emphasizes the virtues of kings. In Shāhnameh these virtues, ideally, include justice, generosity, truthfulness and tolerance. But during Zahhāk’s reign all of these values are turned on their heads. His is a dark reign of terror and oppression, when “virtue is despised, and falsehood is exalted.” Dissenters are put to death and women are forced into the service of Zahhāk. All throughout this time, the two snakes are fed — although it is really the insatiable dragon which lives inside Zahhāk that requires sustenance. More and more people are deprived of their maghz — their brains. The word maghz also means center or core, and so the feeding of the snakes can also be seen as a different form of depopulation — not a purging of humans, but a purge of our core humanity, that which is essential to us.

And so it goes, Ferdowsi says, for nearly 1,000 years. But towards the end of his reign Zahhāk has a very disturbing dream, in which he is shown his own downfall at the hands of a young man called Ferēydūn.

Not surprisingly, Ferēydūn’s roots can also be traced back to Zoroastrian mythology. In the Avesta, the one who vanquishes Aži-Dahāk is a character named Θraētaona. The name, roughly translated as “Possessor of Three Powers,” marks Θraētaona as an apt adversary for a three-headed dragon. According to various traditions, Θraētaona is a godlike or at least superhuman character, with supernatural powers. He is either an immortal or the progeny of an immortal. When he exhales, he projects hail stones from his right nostril and fire-stones from his left. He is a sorcerer-like healer who can cure illness and rid bodies of vermin infestations, turn his enemies to stone, and keep people suspended in the air for days at a time. In the Avesta, Θraētaona is able to defeat Aži-Dahāk with help from the Gods of Water, Wind and Strength. But how does this character appear in Shāhnameh?

The Birth of a Powerful Warrior-King

Just as Ferdowsi transformed the Avestan, three-headed dragon into a decidedly human character, he also turns the god-like Θraētaona into Ferēydūn, a character of more human dimensions who is cared for, nurtured and trained to become a powerful warrior-king.

When Ferēydūn is born his father Abtin has already been killed and his brain fed to Zahhāk’s snakes. But Farānak, Ferēydūn’s loving and protective mother, keeps him hidden and safe from Zahhāk’s minions — first on a farm and later atop the legendary Mount Alborz. In each place Ferēydūn finds a surrogate father: initially the keeper of the farm, and later a sage who lives on the mountain. Both men bestow great care upon Ferēydūn, in stark contrast to the relationship that Ferdowsi establishes between Zahhāk and his father.

At age 16, Ferēydūn returns from the mountaintop and asks Farānak about his true father. When he discovers the truth, Ferēydūn declares that he is going to bring an end to Zahhāk and his reign. But his mother questions whether he can single-handedly defeat Zahhāk, who after all commands vast armies.

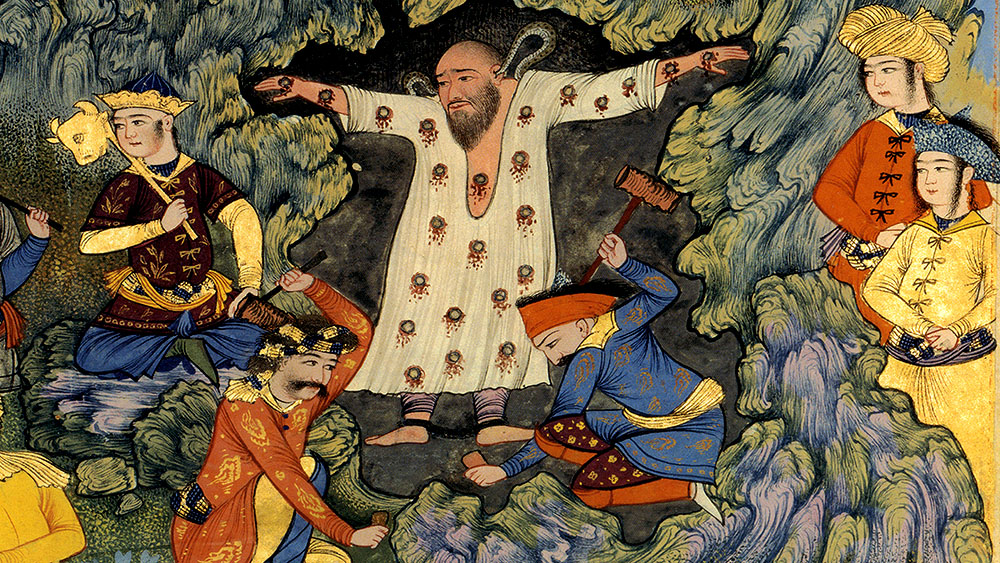

At this point in the story Ferdowsi introduces a character named Kāveh, a blacksmith who has already lost 17 of his children to Zahhāk’s snakes. When his last remaining son is taken away, Kāveh bursts into Zahhāk’s palace and questions his legitimacy as a king. Zahhāk releases Kāveh’s son, but demands that Kāveh sign an official declaration proclaiming Zahhāk a fair and just king. Kāveh tears up the document, and storms out of the palace with his son. He then fashions a makeshift banner from his leather blacksmith’s apron, rallies the Iranian people around it, and leads them to Ferēydūn — effectively supplying him with a provisional army. Ferēydūn adopts Kāveh’s banner as his own, decorates it with silk and jewels, and carries it along with Kāveh and his followers to depose Zahhāk.

There is no mention of Kāveh in the Avesta, Bundahishn or similar texts. It’s unclear whether he appeared in folk versions of the Zahhāk story previous to Shāhnameh, or if he is a creation of Ferdowsi’s imagination. Either way, in Shāhnameh, Kāveh becomes an early iteration of the eventual archetype of the warrior (in Persian, pahlevān), and the patriarch of a long line of warriors. But Kāveh’s place in the Iranian cultural imagination is really as the archetypal resistance fighter — someone who dares to risk everything to stand up to tyranny and demand justice, to speak truth to power and question the legitimacy of an oppressive ruler. Kāveh and his blacksmith’s flag become symbols of popular uprising against the forces of tyranny, symbols that endure to this day.

With the help of Kāveh and his companions, Ferēydūn breaks into the palace, strikes Zahhāk on the head with his mace and brings him to his knees. As he is about to deliver a second, fatal blow, Ferēydūn receives a divine guidance that advises him not to kill Zahhāk, but rather to chain him up and imprison him on Mount Damāvand, the highest peak in the Alborz chain. Once again it’s worth noting Ferdowsi’s modification of the earlier versions of the myth. In most of those versions, Aži-Dahāk is destroyed, or if he’s allowed to live, it’s because vermin would pour out from his corpse and take over the world. Ferdowsi’s telling is devoid of such fantastic notions. Zahhāk is simply locked up in a faraway cave, inaccessible to his cohorts and allies. The implication here may be that our authoritarian tendencies, our own inner Zahhāk, can never be fully destroyed. At best, it can be kept at bay and not enabled — in a sense, deactivated.

At the end of the tale of Zahhāk, Ferēydūn becomes the next king of Iran-Zamin, returning farr and the other original kingly virtues to the throne. Here again Ferdowsi emphasizes the idea that his Ferēydūn is not a god nor even superhuman, but very much an everyman, a stand-in for any one of us when we champion values that counter the greed and oppression represented by Zahhāk.

The poet writes:

Glorious Ferēydūn was not an angel — not forged of musk and ambergris!

Through Justice and Generosity he found virtue;

if you practice these values, then you, too, are Ferēydūn.

This essay was adapted from a presentation by the author at a conference titled “Unveiling the Mythos of Iran,” organized by Dr. Maryam Sayyad & Cross-Cultural Expressions at the Philosophical Research Society.

1 comment