Select Other Languages French.

Thinking about icons past and present, Amal Ghandour remembers Egypt's "Star of the East" on the 50th anniversary of her death.

It was 2010 or thereabouts. We were six cramped into a tiny living room. Balcony doors thrown-open, on a spring evening in Beit Meri, at a friend’s house. A relatively quiet time, I recall — the usual petty Lebanese politics, so the conversation veered towards the banal.

The journalist in our midst threw a curveball: “Who is the one Lebanese leader we would miss were he to die?”

The inquisitor was widely traveled intellectually. In his extreme youth, he was a Maoist revolutionary; in his 30s a self-flagellating leftist; by his 50s, as politically conservative as they come. For him, the businessman-developer, say, in the guise of the late prime minister Rafiq Hariri, had become the model of the hero.

But poor Rafiq, gone then for five years, lost the vote to the living legend, Hezbollah’s Hassan Nasrallah. The first to name al-Sayyed, as Nasrallah is honorifically called, was none other than the erstwhile Marxist. He meant to make a point. Five of us had our quibbles with Nasrallah; the journalist detested him. You had to concede to al-Sayyed his epochal magnitude. His, after all, was the reign of the resistance as liberation, as army, as steadfastness, as identity, politics, community, culture, business. As state. Therefore, epochal.

It’s perhaps the best measure of a leader’s import when lovers and haters alike acknowledge the void in their absence. It’s not the good fortune of all leaders, the destiny only of the iconic among them. They come to embody their era, for better or worse. When one fades, the other inevitably retires with it, and the page turns.

I wonder if we’re hearing the pages turning now in Lebanon?

Outside of Nasrallah, the 21st century, still so very young, has yet to yield its totems in the region. The 20th century closed rich with them across domains and dominions. I don’t know whether Osama bin Laden, who also opened this century and came to epitomize the political dearth that propelled him to stardom and us into dwellers of vacuums, will find a presence in this space. I hesitate more out of modesty than reticence. It’s early yet; patience is a wiser practice than prediction.

But I struggle to pair Nasrallah across geographies and arenas. The tableau doesn’t quite lend itself to what propelled Umm Kulthum and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser soon after they ascended the stage. Nor does it offer the affinities that made the two so complicit in each other’s extraordinary reach, straddling with such ease the cultural and political spheres. Their Zenith was Egypt’s, and Egypt’s was theirs. So was its heartbreak.

You never heard The Lady’s voice in our home: il-Sitt or Kawkab al-Sharq (The Star of the East), as she was known. Politics was the culprit. My parents were not acolytes of Nasser, and so they were no devotees of hers. It was Fairouz, another icon, who animated their evenings: a Lebanese voice, all Levantine tenderness, fervor, and longing. When they listened to her, it was a different Lebanon they imagined. When they wanted to serenade Palestine, they did so to her songs. When it came to love, she, not Umm Kulthum, was the one to pull at their heartstrings.

For my mother — and she was not alone — there was one exception to this rule: the magnificent Asmahan, the émigré “princess” of Syrian Druze descent to whom Umm Kulthum might have forever played second fiddle had Asmahan not died in 1944 at the age of 26. Or so the story goes. It is said of the two divas, “Umm Kulthum sang from the head and heart, while Asmahan sang from the soul and wound.”

But the truth is that the crooning princess, unlike Umm Kulthum, could never have been Nasser’s alter ego. Theirs was the Egypt that was, in fact, on the brink of dethroning hers.

How much do we all miss Umm Kulthum now, though? How much do we miss the big man, the poet himself, including those who loathed him? It’s the void. I suppose it’s in their grandeur that we better understand the smallness of us today; that we better understand, as well, the role their choices played in rendering us so miniature.

Because if they were the embodiments of the rise of Arab nationalism, of the heartland, of the middling classes, of the Arab female as genuine protagonist, of Egypt as the mother of us all, they were also the epitome of their project’s failure.

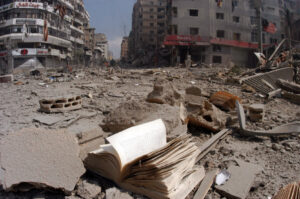

When Umm Kulthum rose, she did so on febrile soil. When she passed in 1975, it felt like the desert. It still does. It’s not that the creative mind capitulated, but that it had to labor in increasingly hostile loci.

Al-Sitt’s last concert was in 1972. Poignantly, Nasser left five years before her, at the age of 52. His flawed legacies include pioneering the modern police state. But none compares with the 1967 blunder — for him and us a burden too heavy to bear. To his funeral, flocked millions; to hers, more. The people knew they were bidding farewell to an epoch and its icons.

Nasrallah’s and mine was the generation that came of political age in the 1980s, inheriting Abdel Nasser’s legacies, none more devastating than 1967’s. The resistance’s victories in 2000 and 2005 were their own resounding answer to decades of Arab defeats against Israel. But not the movement’s mistakes: these have been little different from the ones that brought many an Arab regime so low.

Much like Nasser couldn’t have possibly survived 1967, al-Sayyed couldn’t outlive 2024.

When the Egyptian president died, few could discern the details of the new age with any certainty. Few of us can do so today in the absence of Nasrallah, including, by all appearances, Hezbollah itself.

It’s left for all of us, lovers and haters, to miss him in the void.

On Another Note

This week, an ode to Pope Francis — an icon in the making? — and to the “Solidarity of the Hopeful” he sought to build and nurture. As Thomas Banchoff and Pinkaj Mishra noted in the second installment of the Georgetown University Dialogues, held in Rome, in July 2025:

In his discourse and diplomacy, Francis diagnosed our interconnected global crises—economic instability, social inequality, climate catastrophe, authoritarianism, and war—as failures of moral imagination and practice. He saw nothing inevitable about the worship of wealth and power, the obsession with technology, disrespect for human dignity, and the destruction of the planet. These were human choices, not fate. Francis sought to sanctify the natural impulses of decency and solidarity that spring in all human hearts and to bridge the widening gap between those impulses and our political and economic realities.

At the gathering in Rome, literary luminaries share thoughts on the moral and spiritual influence of this remarkable Pope. Their remarks in the New York Review of Books.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)