Francisco Letelier

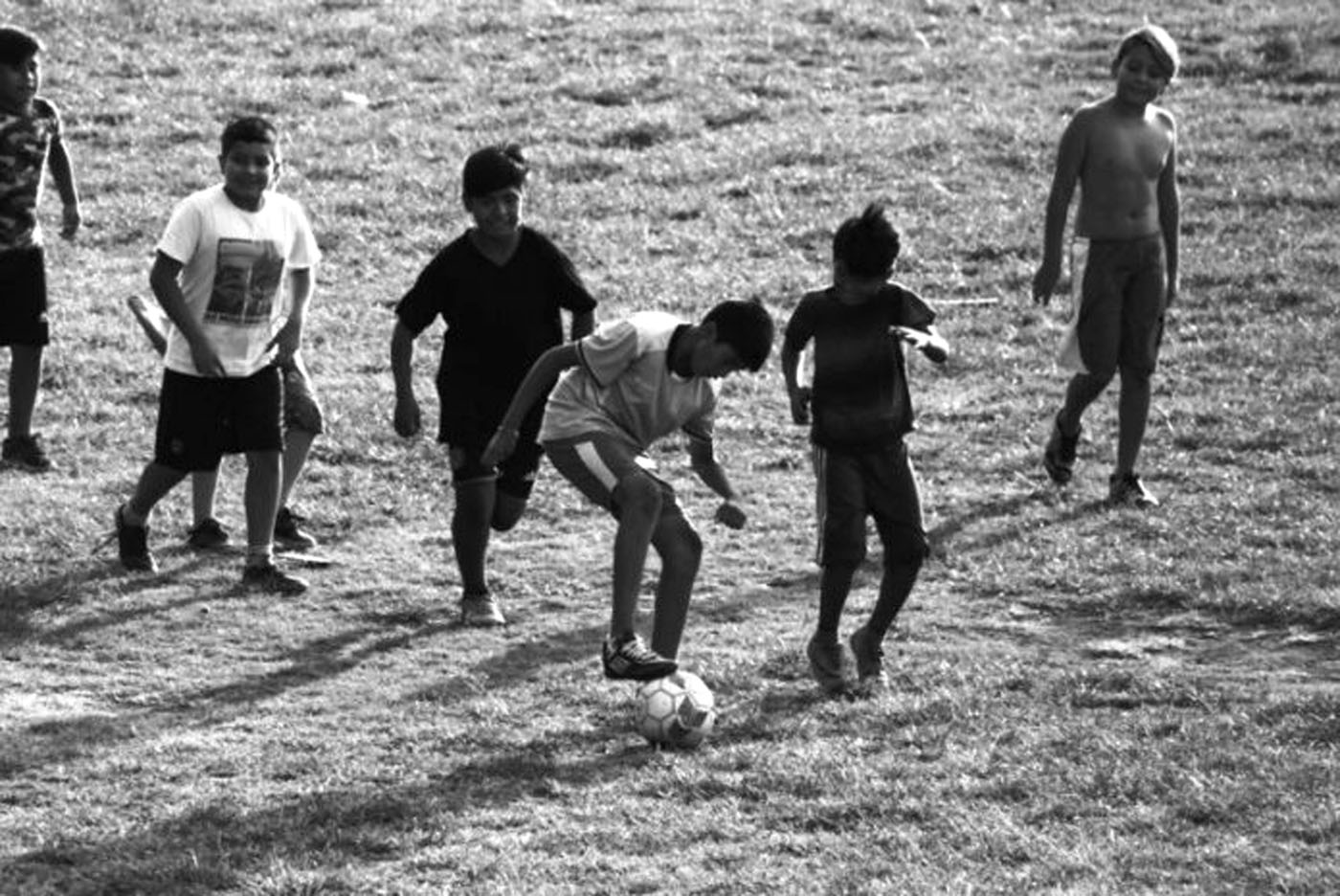

As a Chilean kid in the United States in the ‘60’s, soccer (fútbol) kept my culture alive. When my father and friends from other Chilean and Latin American families decided to form a youth team, I was proud to be a Chilean Penguin. My father and his friends would coach us every Sunday and as our skills improved they wanted our team to join a soccer league. After defeating a few “American” teams, in one of my first brushes with this particular form of cultural prejudice, we were told that we had an unfair disadvantage and were not accepted into the league.

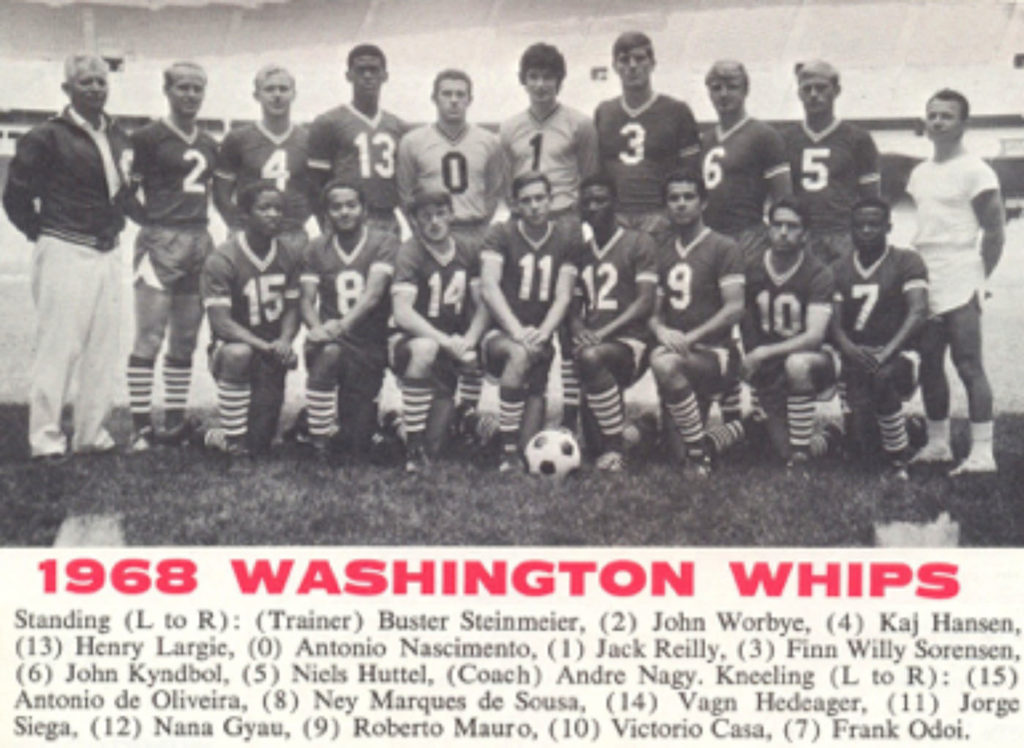

In D.C., we were fans of the Washington Whips, the team that played at the District of Columbia Stadium. Their squad was made up of mostly African, Jamaican and European players, recruited to play in the short lived North American Soccer League that was made up entirely of teams imported from foreign leagues.

Looking back, it’s clear that soccer provided a cultural diversity missing from most sports in D.C.

Once the largest slave trading cities in the 19th century, the District of Columbia grew to be the first majority black city in the 20th. It became known as “Chocolate City” through the 1973 funk song by Parliament, but continues to this day to be divided along color lines.

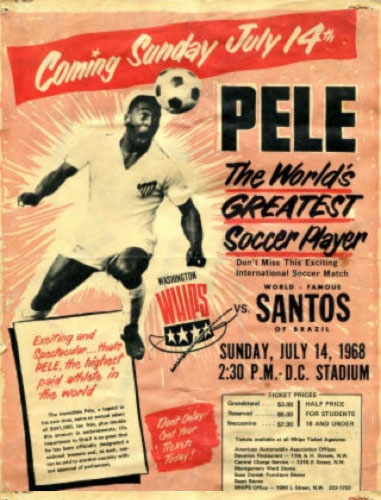

In 1968, we watched Santos of Brazil play the Whips at an exhibition game. Our home team was defeated with world famous Pele assisting on the winning goals; I learned this kind of team playing was what set Pele and Santos apart from many other teams. But deep down, my father was a fan of Colo-Colo, a Chilean national team hugely supported by the working class and named after an indigenous Mapuche hero. Having grown up in “Indian country” in the south of Chile, my father had a deep nostalgia for his pichangas (Quechua derived word for impromptu soccer games) on rough fields with Mapuche boys who called him Colilongko (head of fire) because of his red hair.

People all over the globe have memories like this one, and since the game only needs a ball, a flat(ish) space, and a soccer goal made of whatever is at hand, (sticks, shoes, clothing), the game looks very much the same wherever you go.

In Chile, as in other places in Latin America and the world, soccer has grown to be a huge social force, embodying popular support for indigenous rights as well as for international solidarity through, for instance el Club Palestino or simply Palestino, one of our first division soccer teams. It is hard to imagine a world before soccer, but its global popularity relies on aspects of human culture that use play and games as mechanisms not only for recreation, but also for education, cultural transmission and survival.

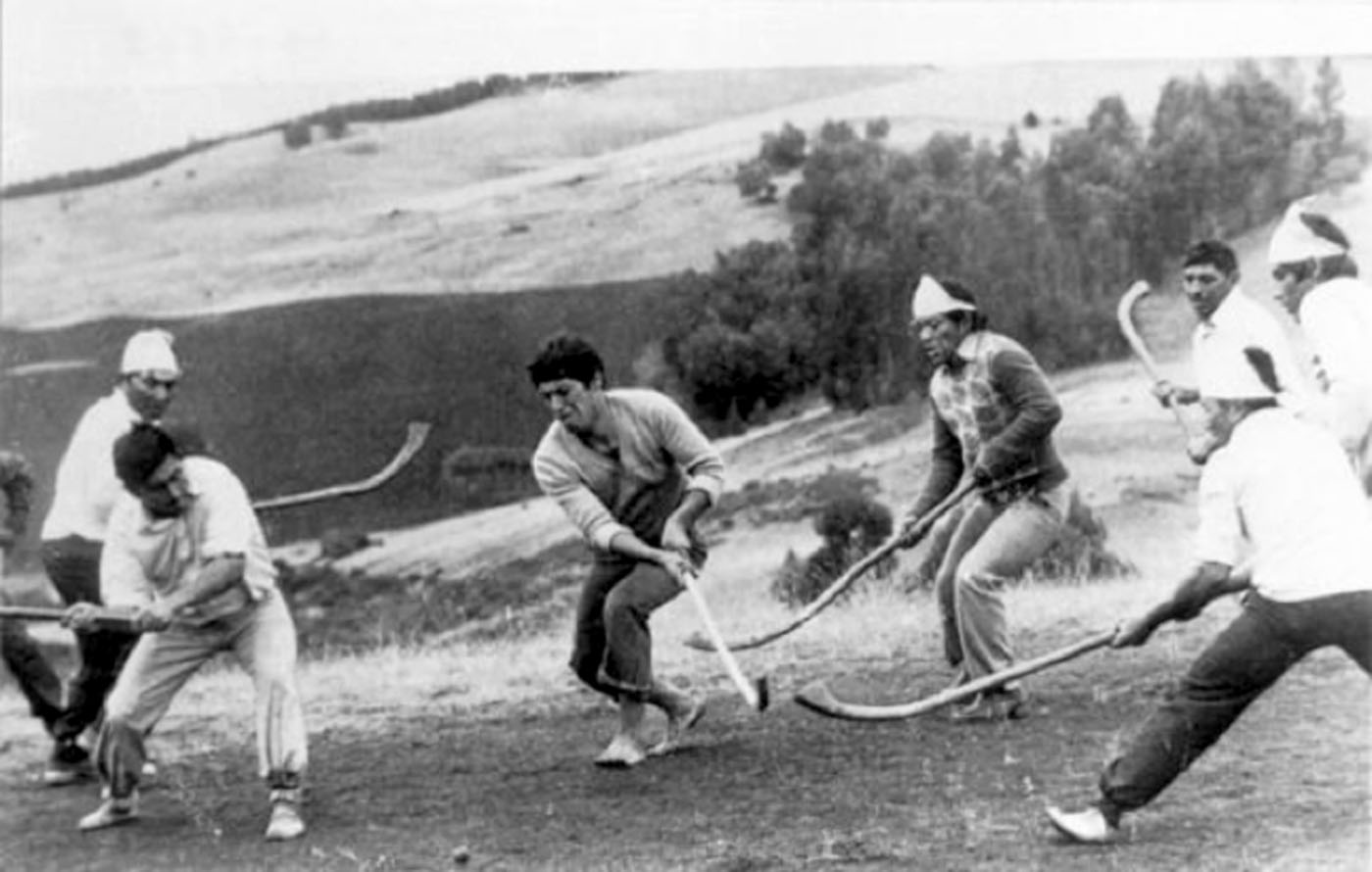

Palin (pal-een), a field hockey played by the indigenous Mapuche, is not just a game, although government efforts to recognize it as a national treasure have only furthered its ranking as such. Palin has been practiced for centuries in order to strengthen political, cultural and spiritual relationships. Traditionally the game was an event replete with ceremony, preparatory rituals and feasts in the days leading up to the match, and included active participation by women, children and elders. An important palin match called for a Nguillatún — a major spiritual rite including song and dance carried out to insure good weather, abundant harvest and health.

It is easy to understand how palin was one of the first practices the Spanish tried to quell in the Southern Cone. During the centuries long wars against the invaders, young Mapuche men dreamt of being effective warriors against the invaders and palin improved dexterity and resistance in combat. Many are surprised to learn that the war for dominion by colonizers over the Mapuche was never victorious. Chileans were only able to drive the Mapuche resistance to the southern edge of the great Bio Bio river; the war lasted centuries and by many calculations continues today. At one point the Chilean Army had to outlaw palin among it own troops, which were made up of mestizo soldiers, seduced by the power and promise of the game, along with a fair amount of gambling and aguardiente (distilled spirits of grape). The English first brought fútbol to Chile and in 1867 the Federacion de Fútbol de Chile was formed. Soon, the game was deeply ingrained in the identity and culture of the nation, supplanting the rebellious qualities of palin even among indigenous Chileans.

Today every nation has a particular relationship with the “beautiful sport” of soccer, or football (as it is known everywhere except in the U.S.). Latino nations and those in the Middle Eastern/North African (MENA) region, however, share interesting similarities. Sports and physical activities have been part of the MENA region for centuries and, like the games of indigenous America, reflect geography, nature and cosmological relationships. Fantasia, a combination of riding and shooting, has parallels throughout the world and is still practiced in the Maghreb region of North Africa. Falconry, a traditional relationship to birds of prey, reveals observations and interactions with animals and birds spanning centuries. Its practice is limited to a few, but may hold keys to renewed relationships with the natural world. Camel racing continues to be an immensely popular sport in the Arabian Peninsula, but it comes with a troubling contemporary twist. Today’s races increasingly have robotic jockeys riding the back of camels. It makes for a scene far from romantic images of Bedouins and others who depend on the ancestral relationship with camels for survival and transportation. Sailing and horseracing are also traditional sports. Their ownership and participation structures long ago moved them away from being popular pursuits and, like the Formula One Grand Prix racing pursued by the royal families in Bahrain and Abu Dhabi, are increasingly the domain of the rich and powerful. Archery and wrestling also have strong traditions appearing in legends and Islamic teachings, but they cannot compete with the now firmly established domain of soccer as the most popular and accessible of sports.

Regimes and political leaders throughout the world use sports to mobilize constituency, build national identity and strengthen legitimacy. The pendulum may swing, but sports are tools used by royal families as well as by those who seek to point out the failures of ousted regimes. High achievements by sporting figures are always an opportunity for power to self congratulate. Global audiences learn about other countries through their sports stars and the state uses their successes to project images of modernity and stability.

As a young athlete and delegate to the 11th World Festival of Youth and Students in Havana, Cuba in 1978, I was chosen by the Chilean delegation to run a lap during the opening of the festival. Several others were chosen, including young athletes from the Algerian, Moroccan and Palestinian delegations. We looped the Estadio Latinoamericano behind Alberto Juantorena (El Caballo), the larger-than-life Cuban athlete who won both the 400 and 800 meter titles at the 1976 Montreal Olympics.

Twenty-two African nations boycotted those Olympics. Organized by Tanzania, the boycott was a protest against the participation of New Zealand in the games, as their team had toured apartheid South Africa. Sports provide a dramatic arena for social protest and none more so than the Olympics. The famed Black power salute by American gold medalist, Tommie Smith and bronze medalist, John Carlos at the podium after the 200 meter race at the 1968 Mexico City summer games led to their banning from the US team, but the act became iconic as a symbolic protest. As Fidel Castro reminded us in his speech at the stadium on that day in Havana, “El deporte es tambien, la revolucion” (sports are also the revolution).

Those were inspiring days, shortly after my family’s escape from the dictatorship in Chile and my father’s subsequent assassination by Pinochet’s agents. As a member of the congressional delegation, along with four others from diverse countries heading a tribunal in the Cuban Congress building, we welcomed Yasser Arafat and sat to share a cup of tea with him before he addressed delegates from 125 countries. At the time, Palestine was bidding for entry into FIFA, having pursued membership since 1946; the nation only gained entry after numerous attempts in 1998. In 2005, Palestine proposed that FIFA suspend Israel from competition because of its apartheid policies against them, but was unable to gain needed support for a vote. Nonetheless, FIFA members did support an amendment to form a committee to monitor Israel’s compliance with FIFA guidelines.

Since then Israel has continued policies of non-compliance through travel restrictions, arrests and attacks on players, the refusal to allow the building of facilities on the West Bank and the banning and tear-gassing of Palestinian sports events. The call for a suspension of Israel remains ongoing.

The Arab Spring uprisings for democracy and freedom in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Bahrain, Syria and Yemen unleashed events that created today’s political landscape. During this time, the role of football supporters in opposition to repressive regimes came to the forefront. These regimes controlled the public space, diminished democratic principles, violated human rights and closed down competitions and stadiums to silence opponents and prevent gatherings.

In Chile, our national stadium was put to the same use as Kabul, Afghanistan’s Ghazi Stadium under the Taliban (1996-2001). In both nations, stadiums were used to punish, torture and murder perceived political and religious opponents. Just recently, on September 9, 2022, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) finally approved a strategic framework on human rights. The IOC president stated that the mission of the Olympic movement is to contribute to a better world through sport and that, “human rights are in fact firmly anchored in the Olympic charter.”

The new framework is an important move following the release of a report by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michele Bachelet, on serious human rights violations against Muslims in China’s Uyhgur Autonomous region. (Bachelet, the former president of Chile, was herself a victim of imprisonment and torture by the Chilean military dictatorship led by Augusto Pinochet from 1973 to 1990.) Violations of China’s minorities came to global attention as it hosted the Winter Olympic games in Beijing earlier this year. Many feel that during the World Cup, scheduled to begin on November 20, 2022 in Qatar, similar revelations will also come to world attention.

Today, controversial negotiations between the IOC and the Taliban regime in Afghanistan are now underway. Successful negotiations would lead to the Taliban allowing women and girls to play sports, but the newly adopted IOC framework also compels the committee to address basic human rights regarding violence, health, livelihood, identity, and the right to participate in public life. Nonetheless, in early September from the Panam Sports General Assembly in Santiago, Chile, IOC director James Mcleod expressed satisfaction about negotiations with the Taliban regime. Interestingly, negotiations began only last year in a meeting arranged by Qatars’s emir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani.

It’s a confusing moment in Qatar, whose emir has plenty of reasons to urge for negotiations of this kind. The nation is vying to represent the Arab world as host of the World Cup and has drawn support from across the member states of the Arab League. They see their bid as an opportunity to bridge the gap between the Arab world and the West, but Qatar is an example of the way control of oil and gas continues to be central to power, wealth and conflict around the world and the landing of the World Cup in Doha underlines this fact.

Most readers of international events know that Qatar faces intense criticism from human rights groups over its treatment of migrant workers, but many do not understand the scope of the infrastructure built for the World Cup, and do not realize that such workers and other foreigners make up the majority of the country’s population. FIFA President Gianni Infantino has urged countries to avoid protesting against Qatar’s human rights record, “Please let’s now focus on the football! We know football does not live in a vacuum and we are equally aware that there are many challenges and difficulties of a political nature all around the world.”

Blasted by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, a slew of political leaders, football associations, athletes and fans, the comments by FIFA sound altogether naïve in a world that depends on millions of migrant workers to keep its wheels turning. Human Rights Watch does, however, admit that Qatar has made notable reforms, but also finds them “narrow and weakly enforced.”

Coupled to existing laws curtailing the rights of women and the arrest and abuse of LGBT people, Qatar has a lot on its hands. Many are calling for a fund to compensate harmed migrant workers (#PayUpFIFA), a strategy recently rejected by Qatars’s Labor minister. Qatar has rightly countered that European nations have no problem with Qatar when entering energy agreements and partnerships. To state that double standards exist the world over as we collectively plunge into the age of climate change is easy. The plights of migrant labor must be addressed not only in Qatar, but also in the liberal democracies of Europe and the Americas. Few perceptive critics concerning Qatar feel that compensation for laborers will forestall the harvest of globalized power and control represented by the World Cup.

The first match of the World Cup will be between Ecuador and the host nation, Qatar. Chile lost its playoff match to Ecuador but hoped to regain its standing for competition in an official complaint filed with FIFA concerning the nationality of one of the players of the Ecuadorian team. The news from both Chile and Ecuador was dominated by this squabble for weeks, and even as it became clear that the ruling would favor Ecuador, it also became evident that the fervor of Latin American nations to qualify for the largest sporting event in the world overpowers those who would boycott the event.

Latin American players prefer to demonstrate on the field and through media. Socrates, the legendary Brazilian midfielder who scored 22 goals in two World Cups, led pro-democracy movements against the Brazilian dictatorship. Chilean player Carlos Cazely is well remembered for his opposition to the Pinochet regime and his support of the “No” movement that led to democracy. Today the Colo-Colo team has a club of fans known as the White Claw Antifascists, Antifascistas de la Garra Blanca. White Claw fans participate in the Voz del Sur organization along with other anti- fascist fans of soccer clubs in Bolivia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and Colombia who combat racism, xenophobia and homophobia on the streets and within stadiums.

It has become normal for Chilean national teams to make political statements concerning movements for social justice both on and off the field, despite admonitions and fines from government and sports authorities. The fact that Chile is vying to host the World Cup in 2030 is also an influence on the type of politics and the actions taken by fans, players and teams.

The upcoming World Cup will occur at a time when protests are increasing in Iran over the death of Mahsa Amini, the 22 year old Kurdish woman detained by morality police for allegedly wearing her hijab head scarf “improperly.” Mahmood Ebrahimzadeh, a famous Iranian player who played in past World Cups, now lives in exile and is one of the many Iranian sports figures in exile and within Iran who are calling for action against the regime. Earlier this year, security forces barred women from entering the football stadium in Mashhad, dispersing them with pepper spray. Many are now calling for FIFA to eliminate Iran from the World Cup.

Mohamed Salah is Egypt’s great soccer star, playing for Liverpool’s Premier League. With 44 goals in the 2018 season he set a scoring record, grabbed headlines and became an international celebrity. It is said that one million Egyptians wrote his name on ballots in the presidential election of 2018. Salah is known for his generous charitable works and his careful negotiation of political space. His reticence over political matters has been criticized in a nation where ultra fans are politically outspoken and participate in violent and often deadly clashes with regime security forces, but his role as a cultural and religious ambassador is undeniable. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sissi never misses the opportunity to use Salah and soccer to bolster his plan of government and bend it to his own particular vision of the nation, but as noted elsewhere it’s a practice used by rulers before and ever since the sport of soccer extended its influence over the world.

Many, like me, are often perplexed by how big sports competitions dominate the attention of the multitudes, but those who ignore the larger meaning of international sports only limit their understanding of humanity as a whole. The intersection of soccer with social and cultural conditions is unique in each individual nation and provides understandings not easily found elsewhere. Impulses that lead to games and play are central to humanity and tragically many of these have been hijacked by structures that reduce sport into something less than what it could be.

In my vision of a possible future, Mapuche warriors of all genders on horseback wave palin sticks as they join other riders on camels, who race with magnificent falcons towards a place where we gather to put an end to the mining and extraction practices that have brought our cultures, histories, games and common survival to an undeniable precipice. It’s a fanciful vision, so in the meantime I will watch some of the World Cup, knowing that we live in interesting times and that anything can happen, and probably will.

Resources

“Sport and Political Leaders in the Arab World,” Dr. Mahfoud Amara.

“Qatar minister accuses Germany of ‘double standards’ in World Cup criticism,” Reuters.

“Political Football: The World Cup’s Middle East Challengers,” Atlantic Council.

“Islamic Republic Resorts To Threats To Keep Footballers Out Of Protests,” Iran International.

“Egypt’s Mohamed Salah, Footballer with a Big Heart,” Africa Report.

“Palin: un encuentro espiritual, social y político,” Museo Mapuche.

“Palestine ‘lacked support to ban Israel from Fifa,” Al Jazeera.