Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt by Andrew Simon

Stanford University Press 2022

ISBN 9781503629431

Mariam Elnohazy

In the autumn of 2017, an American friend of mine decided to buy three kilos of cassette tapes from the Friday market near Cairo’s citadel, where you can purchase anything from furniture and antiques to livestock and the latest iPhone. He invited me to his apartment, eagerly hoping that my excitement at this find would match his. I rolled my eyes at what I thought to be a typical move by a foreigner in Egypt, enchanted by the aliveness of objects long dead in the West. Seeing the lag in my reaction, he started playing a cassette tape. The recording started off with the raised voice of a man named Ahmed, yelling over an absence of background noise. His accent was provincial, but indiscernible to me, and he seemed to be speaking to his family. To the recorder, he narrated his days in scant detail: touching on his work day (“I go to work at six and leave at sundown”), speaking of coworkers (another Ahmed, from Daqahliyah), and talking about how much he missed food from home. Between every tidbit he offered, he thanked God: “alhamdulillah.” He asked after individuals, stopping briefly between each name, as if expecting a response. There was a lot of dead silence in between the man’s narrations, a recording style which presumably wouldn’t be tolerated in the age of WhatsApp voice notes listened to on 2x speed.

After trying to make out the first tape, I wanted to hear more, feeling the uneasy satisfaction of overhearing a conversation not meant for your ears. We switched the tape, tuning into an entire family talking over each other, presumably sending a message to another absent son working abroad. A third cassette was a mixed tape of various pop songs. And so on. These orphaned tapes, removed from their contexts, each provided a snapshot of intimate relationships long past, yet now resuscitated by playing a cassette tape.

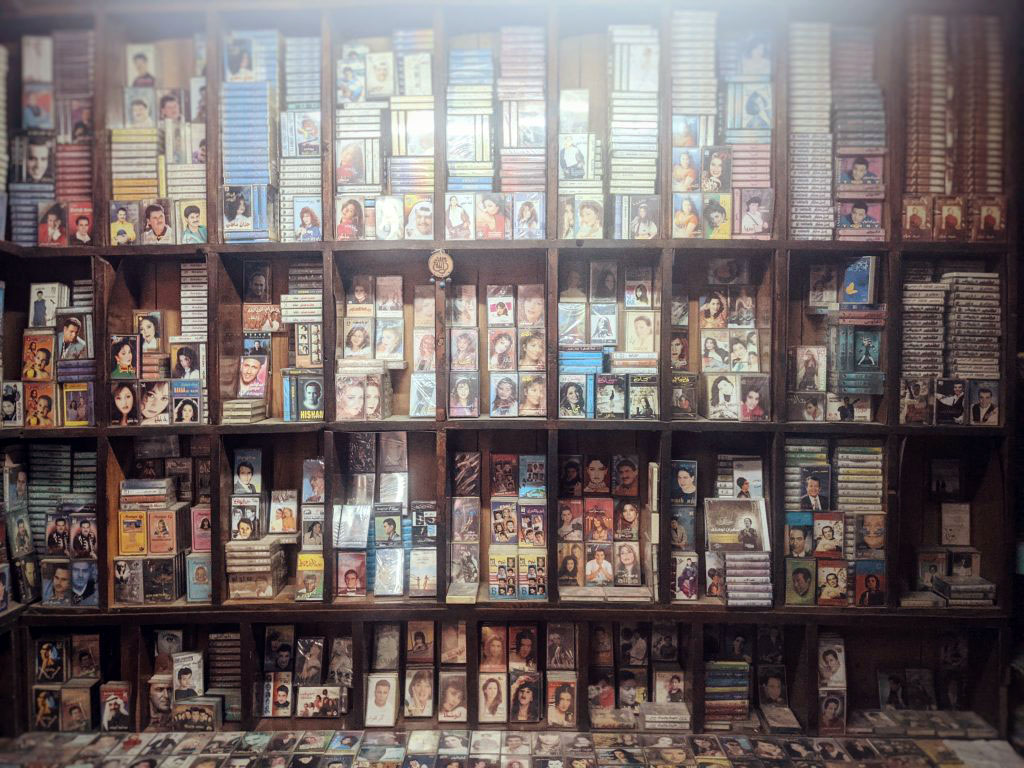

Andrew Simon’s Media of the Masses: Cassette Culture in Modern Egypt begins similarly, with a collection of cassette tapes on display at a Cairo kiosk in 2015, sold as collector’s items because they are no longer in demand. Simon’s work seeks to historicize tapes like these and the ones my friend bought at the Friday market, beginning with the experience of Egyptian laborers working in oil producing states in the 1970s and ‘80s, buying cassette tapes and players. He glosses over previous scholarship which discusses tapes that carried personal messages between Egyptian migrants in the Gulf and their loved ones, instead focusing on the exchanges of the tapes themselves, often brought to Egypt in suitcases by men working in the Gulf. The influx of these goods represented a newfound culture of consumption that was ushered in by then-President Anwar Sadat.

Print materials and sonic encounters demonstrate the desirability of the cassette tape in Egyptian society, and the importance of the mobile technology in creating an ideal, modern life for the everyday Egyptian, no matter what class or city they came from.

Simon writes a material history of the cassette tape, tracing the circulation, disappearance, and reproduction of tapes through the annals of Sadat’s Open Door Policy, enacted in 1974. One year after Egypt’s oft-lauded victory against Israel in the October War, Sadat opened Egypt to foreign business investment. The transition from a socialist economy to a mixed public-private economy was not smooth; rather, it was riddled with political clashes, violent riots, mass imprisonment, and consistent heavy militarization. To incentivize investment in Egypt’s newly open economy, Sadat politically realigned Egypt with the West, pursuing a peace initiative with Israel, among other moves, to cement the partnership. In addition to the massive geopolitical and economic transitions that it caused, the Open Door Policy created an irreversible cultural shift in Egyptian society.

Simon follows the cassette tape as an attempt to imagine the soundscape of Egypt’s liberalization period. To understand the role of cassette tapes in this transition era and, more specifically, in Egypt’s newfound consumerist culture, Simon relies first on print materials: magazines such as Rose al-Yusuf, newspapers such as Al Ahram, and photographs printed and circulated on Facebook pages that mention or depict the role of cassette tapes in daily life. He then traces circulation and listenership through encounters with cassette players and audiocassettes in shops in the Cairo district of Shubra, governmental spaces such as the Music Library, and religious spaces such as the Azhar academy. These print materials and sonic encounters make up a “shadow archive”: visual, textual, and audio materials that exist outside of official Egyptian national archives. They demonstrate the desirability of the cassette tape in Egyptian society, and the importance of the mobile technology in creating an ideal, modern life for the everyday Egyptian, no matter what class or city they came from.

In 1976, two years after the Infitah, the economic opening, a reporter for the popular magazine, Rose al-Yousuf wrote, “If you ask any Egyptian traveling abroad about what he will buy first, he will immediately answer you: a cassette player.” Simon follows the cassette tape domestically and abroad, and even extends his analysis to the theft, smuggling, and piracy of tapes. He uses the movement, appearance, and disappearance of cassette players to shed light on different pressure points of the transition era. The customs dramas and border disputes, theft of cassette players publicized in popular magazines, noise pollution ordinances, and different legal cases around cassette piracy all point to tense moments in the making of an explosively consumerist society.

As Simon argues, the mobile listening culture that accompanied the large-scale distribution of cassettes decentralized state-controlled Egyptian media, opening all kinds of possibilities for listenership across many levels of Egyptian society. As such, the role of the state as the mediator of culture, dictator of consumption, and arbiter of ethics was under threat. Simon delves into this threat by focusing on three main individuals whose words he casts as oppositional to the Egyptian state. Shaykh Antar, Ahmed Addawiyya, and Shaykh Imam were all figures whose popularity came from cassettes: the first a Quran reciter; the second, a popular (sha’abi) singer; and the third, a reciter-singer. All three of them were deemed vulgar by the state and its high culture gatekeepers.

At the height of Shaykh Antar’s recording career in the 1980s, Al Azhar banned him from reciting the Quran, citing lack of formal training and mispronunciations as reasons for censorship. Ahmed Addawiyya, the popular sha’abi (singer) whose 1976 hit album “Adawiyya in London” outsold the classical legend Abd al Halim Hafez’s “Qariat al Fingan” by twice as many units, was deemed vulgar in lyrical style, melody, and content. Shaykh Imam was imprisoned multiple times for his musical production, which served as the sound of the 1972 student uprising, and his songs often mocked Sadat’s policies and called for solidarity between workers, farmers, and other marginalized people across Egyptian society.

Simon especially hones in on the song produced by Shaykh Imam and poet-songwriter Ahmed Fouad Negm, “Nixon Baba” (featured in the above video), which satirizes then-President Richard Nixon’s 1974 visit to Egypt and Sadat’s desperate pandering to the Americans with the cheeky opening line: “Welcome Father Nixon, O you of Watergate.” All these figures, despite being oppositional figures in relation to the Egyptian state, enjoyed popularity on cassette tapes, and were listened to in cars, homes, and shops — far from the control of Egypt’s cultural gatekeepers. Some writers, however, have disputed the popularity of Shaykh Imam, claiming that his music was made to be instrumentalized by a small sector of leftists, students, and the intellectual elite who felt aligned with the topics he addressed. Others hold that Shaykh Imam has largely been forgotten, part of a distant past linked to the crushing defeat of June 1967.

Simon’s provocative title, Media of the Masses, leaves me questioning: who are Egypt’s masses, what do they listen to, and who sings for them? In a political and discursive configuration where “popular” is deemed as oppositional due to censorship measures and legal restrictions, it is difficult to identify exactly what defines the genre of popular music, what it is rooted in, and whom it serves. Outside of a reactionary paradigm, we can perhaps think of popular music as one that employs catchy melodies to address universal themes such as love, marriage, birth, death, work, agriculture, and the cycle of life. Of course, these practical worldly topics could extend to political unrest or austerity, but there is something missing in the casting of Ahmed Addawiyya as the David to high culture’s Goliath, or Shaykh Imam as the voice of revolution. Simon’s historical charting of the popularity of these figures and their circulation through cassette tapes leaves room for further inquiry into the effect these “popular” artists had on their listeners, and how widespread their influence was. How were listeners throughout Egypt moved, or repulsed, by the newest cassette release?

In the comments section of Ahmed Adawiyya’s hit “Kollo 3la Kollo” on Youtube (featured above), a listener writes “when I listen to Adawiyya, I remember the wonderful breeze of the summer.” Another, addressing Adawiyya directly, writes: “This reminds me of primary school days where your cassette tapes would be stacked on the table…”

Our contemporary period of unprecedented decentralization and the unrestricted accessibility of music has evolved from the cassette tape era. Only now, on the internet, we can learn about the affective relationship listeners have to musicians and their musical production. Weaving through comments sections, we can uncover more about what polarizing artists mean to individual listeners in an intimate way.

In the absence of an internet archive that would provide insight into listener reactions from the 1970s, Simon helps us understand how cassette culture could have affected subject formation in the making of modern Egypt. Simon is not the only one looking to cassettes as archives of alternative histories; The Syrian Cassette Archives, a project founded by Mark Gergis and Yamen Mekdad, also looks to cassette culture to understand more about Syrian musical heritage and social history. As a part of this revisionist wave, Media of the Masses fills the gaps of historiographical elisions past by tracing the mechanisms of the various soundscapes that served as a backdrop to Egypt’s liberalization period.